Three options at one address

By Deborah Salomon • Photography by John Gessner

Houses can be 3-D textbooks chronicling history or sociology.

The first cottages built by the Tufts family were close to the hotel and without kitchens, since renters took their meals in the Casino building. Later on, people who stayed longer, perhaps for the winter “season,” brought children (who attended a schoolhouse built for this purpose), and needed cooking facilities and a maid’s room. Front porches, perhaps a screened one on the side, were obligatory for sitting and conversing with neighbors out for an evening stroll. Fireplaces got them through the winter. Before air conditioning, everybody left in May.

After nearly two decades of attracting wealthy urbanites, the cottages — now built on spec rather than commissioned — became smaller, plainer. Some were occupied by upper-level resort staff and village merchants, others by families drawn to Pinehurst’s rung on the social ladder. The best had enough land to expand.

Acadia Cottage, built in Old Town in 1917, conforms to some of these parameters but with a checkered history. Hugh McKenzie was the first owner, followed by another five by 1951. Only one — Mrs. W.H. Nearing — appears in the Pinehurst Outlook social listing of comings and goings. Records show that a fire burned off the wood-shingled roof, which was replaced by fireproof shingles for $300.

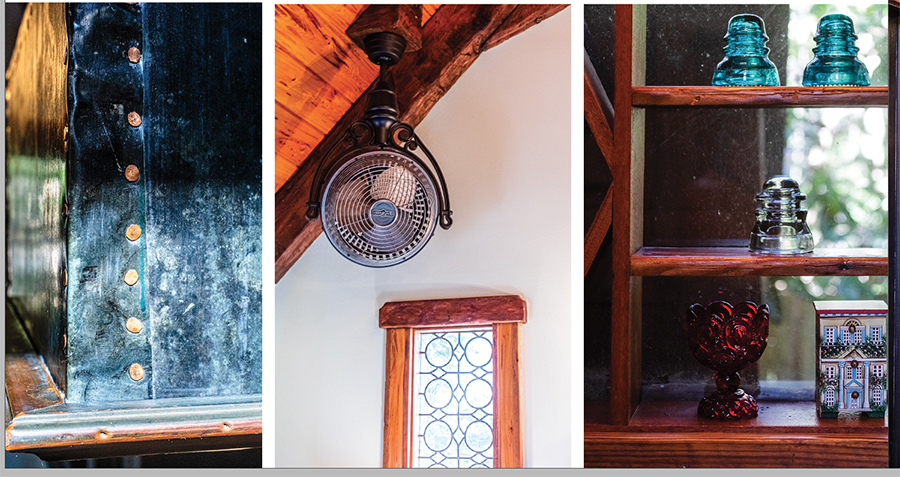

Now, beyond Acadia’s back door or through a side gate lies a magic kingdom — a mossy courtyard with a fire pit, a 50-foot-long and 11-foot-deep pool, massive stone benches for sitting and boulders for diving, a darling little pool house and a roomier guest house, both fully serviced with heat and AC, kitchenette, sitting room, a sleeping alcove and bathroom. No piece of this enclave appears strictly utilitarian. Each, whether it’s a cabinet or a conveyor-belt ceiling fan, offers an artistic, craft or historical component.

Antiques co-exist peacefully with reproductions and artifacts. Only living there affords enough time to notice, and appreciate, the array.

This enlargement and renovation was the brainchild of David Connelly, a Chicagoan with four athletic children, who wanted a vacation haven and found the overgrown back lot completely hidden from street view ideal. Connelly, a self-described wannabe architect, purchased the dull, dated but well-built “brownie house” on half an acre in 2000 and went to work. He and his contractor sourced stone for outbuilding walls from western North Carolina mountains, lumber from a demolished tobacco barn and the Reynolds estate in Southern Pines.

On a damp day, the boards still smell like tobacco.

They removed walls in the two-bedroom cottage, creating an open living/dining/den space, and installed a modern kitchen that, somehow, looks like it’s been there forever. A bath/laundry room with a half wall tile shower was added, as well as a Carolina room off the dining area. Details mattered; moldings aplenty, sometimes painted a color different from the walls, delineate the 10-foot ceiling. Over the front door, a transom pane. An old-timey wood screen door fit the timeline. Then, to frost this cake of many layers, a faux specialist painted wide pastel stripes from Marshall Field’s shopping bags on a powder room’s walls. Even more striking is the colored grid applied to the kitchen floorboards creating the look of scuffed linoleum, circa 1940s.

The dull brownie house, called Acadia now, inside and out, glowed a pale green, neither mint nor avocado, froggy nor kiwi, but so organic to the setting that Jay and Kim Butler, who purchased the property in 2010, didn’t paint over it.

The story of their acquisition rings familiar:

The Butlers, from Virginia, with a second home at Nags Head, spent a weekend in Pinehurst. Kim had never been here. “We rode by the house on a Saturday and saw it was for sale. It had great curb appeal,” Jay recalls.

After 10 years, Connelly was ready for another project.

“I had to have a pool, so I loved that feature,” adds Kim, retired from the retail pool business, with an avocation for collecting mid-century modern furniture and unusual décor accents.

“We just liked the quaintness,” says Jay, an executive in a family recycling business. Golf was a draw, confirmed by memorabilia decorating walls in the TV den opposite the living room. Most of all, “It was in move-in condition, exactly the way we liked it.”

About a month later, they did exactly that.

Soon, their friends were lining up for invitations to test private guest and pool house accommodations which set this address apart from Pinehurst estates with designated guest quarters under one roof. Their verdict, Jay says: “Kinda cool.”

Each outbuilding has only one room — but enough features to fill a catalog, like a queen-sized Murphy bed hidden by wood paneling suggesting a library, or chapel. “Antiqued” cabinetry and metalwork, distressed painted pieces, leather chairs with half-moon ottomans, beadboard, an old porcelain sink, refrigerated drawers, vaulted wormy chestnut ceilings illuminated by stained glass inserts, a drop-leaf kitchen work surface that, with leaf raised, becomes a table. The guest house has a round-topped Dutch front door rescued from a wine cellar, and the pool house bathroom, with direct access to the yard, is split into shower, toilet and vanity sections along a narrow hallway.

Obviously, planning coupled with imagination were at work here.

However, fitting so much furniture into relatively small spaces can be challenging. Not for Kim Butler, who positions modern glass sculptures on a rustic table and adorns dressers with large, bare branches. Throughout, she uses traditional wide-slat wooden blinds.

Back in two-bedroom Acadia — compact but perfect with the living area opened up and furnished with Kim’s retro pieces — one standout is a small drop-leaf kitchen table made of aluminum tubing and Formica, with vinyl-upholstered chairs. “I thought about an island,” always convenient in a kitchen with limited counter space. Instead, Kim settled for what has become an emblem, a conversation piece.

Kim’s collection of colored pottery pitchers brightens a bookcase flanking the shallow living room fireplace, converted to gas for safety; other pottery and glass pieces cover tabletops. Texture, texture everywhere. The chandelier over the dining table is made of wood, and the upholstered club chairs qualify as shabby-chic. No two lamps claim the same parentage.

Kim furnished the screened porch in Chinese red lacquer and black wicker, strong colors that pair with the darkened knotty pine floors milled from trees cut out back.

Room to room, comfort prevails.

Who would guess what’s inside from strolling by, as Annie Oakley might have done when she lived in an apartment across the street? The well-tended walkway, flower beds and porch provide no hint.

Acadia may lack the pedigree of homes built before and during the Roaring ’20s — the Mellons and Rockefellers never stopped here. The Fownes and Marshalls opted for bigger and fancier rather than livable and convenient.

But, after 10 years walking to the village for dinner after a relaxing float in the pool, then chasing the dogs around the fenced yard, Jay Butler concludes, “It’s just a good place to have a home.” PS