Or, how to buy a white elephant, inside unseen

By Deborah Salomon • Photographs by John Koob Gessner

It takes a village to support a castle. But castles are so . . . yesteryear. Most have become tourist attractions or TV locations. Duncraig Manor and Gardens isn’t exactly Downton Abbey, although rather grand for Southern Pines village, circa 1920s, when moneyed Northerners flocked to outdo each other residentially in the newly chic winter enclave.

A pair of these, Quaker Oats heiress Mrs. J.H. Andrews and her daughter Helen Lohman, hired Alfred Yeomans, the nephew of James Boyd, who was to architectural/landscape design what Chanel and Patou were to couture. This would be a huge jewel in Yeomans’ crown.

Except the homestead differed from the Georgian, Federalist, Victorian, New England saltbox, Arts and Crafts and other architectural styles dominating Weymouth. Later named Duncraig by subsequent owner Dr. George Matheson, who had ties to the Scottish Duncraig Castle built in 1866, this was more lodge than castle, executed with a whiff of Tudor, suitable for a newly minted English lord with eight children wanting sprawling summer digs in hunt country. Duncraig has nine bedrooms, 10 bathrooms, a servants’ wing, a quasi-commercial kitchen, finished basement, spa, a garden tea house, groundskeeper’s apartment over the garage, even a nook in the dining room equipped for serving a buffet.

Total: 12,680 square feet . . . and counting.

At completion in 1930, it’s safe to assume Duncraig made a big splash on the bend of Connecticut Avenue.

These days, only a business could justify such space.

The first business was a group home for emotionally disturbed children, operated by Constance Baker. That use did not please neighbors; the home closed in the 1990s. The property, a maintenance money pit, deteriorated as it passed hands.

Caroline and Donald Naysmith are in the business of restoring threadbare mansions as B&B/event venues. Their previous projects — now on the Register of Historic Places — took them to Colorado, Missouri, New York state and Charlotte. Their children operate several.

The Naysmiths have seven children and 30 grandchildren (including three great-grandchildren), so Duncraig works well on holidays.

But nobody calls it rustic or even family style. Beginning with an Italianate fountain installed by a son-in-law in the walled courtyard, continuing with heavy formal furnishings upholstered in dark brocades on the main floor with lighter, brighter hues upstairs, this B&B suits ghosts seeking retro opulence. Ghosts who expect a lily pond, swimming pool, kennels for the hounds, and formal gardens spreading over nearly 5 acres.

On first approach, Duncraig appears the stretch limo of Southern Pines showplaces, somewhat reminiscent of Loblolly, also faintly Tudor with stucco exterior designed for a Boyd relative by Amar Embury II in 1918.

Might Mrs. Andrews and her daughter have been in competitive mode a decade later?

The Naysmiths discovered Duncraig while in town for a musical event; Donald sings gospel and classical. For Caroline, it was love at first sight. She had Don stop the car so she could ring the doorbell, see what was what.

She never got inside. Her reaction, nevertheless: “This house needed me.”

They purchased the property in 2017.

“We are people of faith,” Don said. “We made it a matter of prayer.” Also a matter of money, since the 18-month restoration cost in the low seven figures.

Where to start a tour? The sunken “salon,” aptly named since a room comfortably housing a baby grand piano and an even longer harpsichord exceeds either living room or parlor. Its walls, like those throughout the house, are textured plaster with unusual rounded corners. Some were wallpapered in brocade which, when removed, revealed mold. The gleaming pegged floors are mostly stained. Dark, heavy beams bisect the ceiling. Here, around a massive coffee table, guests gather evenings for wine and hors d’oeuvres before heading out to dinner.

The Naysmiths found furnishings and paintings hither and yon, mostly from dealers in North and South Carolina. For these forays, they attach a trailer to the car and bring it back loaded. No auctions, which are too time-consuming, Caroline says. “We love period antiques of the ’20s and ’30s, when the house was built.” In the salon, this includes throne-sized armchairs in royal purple, an inlaid Asian highboy, both authentic and reproduction Tiffany lamps. Caroline made the drapes covering paned casement windows here and throughout “while I was waiting for the rest to be done.”

Adjoining the salon, a game room/library with burgundy walls offers not only chess and books, but a snarling bear rug.

Watch where you step.

Don relates the story of the dining room table, which looks folksy considering the ornate chairs. He found a fallen cherry tree in the Adirondacks, had the trunk milled into 10-foot lengths and kiln dried with the planks joined into an 11-foot table top set on carved pedestals.

A small (but obligatory for the era) butler’s pantry leads into a mammoth kitchen more utilitarian than magazine, with ceramic tile backsplashes, a square island and a Blue Star gas range tucked into a niche — perfect equipment for a wedding caterer but a bit much for the Naysmiths, who as concierges are required by law to live on the premises.

Main floor rooms are joined by hallways; in one hangs a collection of cow bells. Other collections include Royal Doulton historic character mugs and antique chamber pots.

The front hallway running the length of the house must be longer than a bowling lane.

Each of the guest rooms is named and furnished after places the Naysmiths have visited, including Nagamo, Vienna, Jamaica, Charleston, Budapest. Perhaps the most charming are smaller bedchambers in the servants’ wing, each with a tiny vanity sink.

Bathrooms have been modernized only when necessary, otherwise leaving tiles and fixtures intact, adding to the authenticity. Some have extra-long soaking tubs.

The terraces and gardens, beginning with the front courtyard and, in the rear, stretching on all sides as far as the eye can see, only enhance the estate atmosphere.

However, from a business angle this home-away-from-home for guests trading up isn’t quite what the Naysmiths planned. The B&B and Airbnb worked out, but town regulations limit them to serving only breakfast, not luncheon meetings or dinners. Duncraig is allowed to host only 20 events per year.

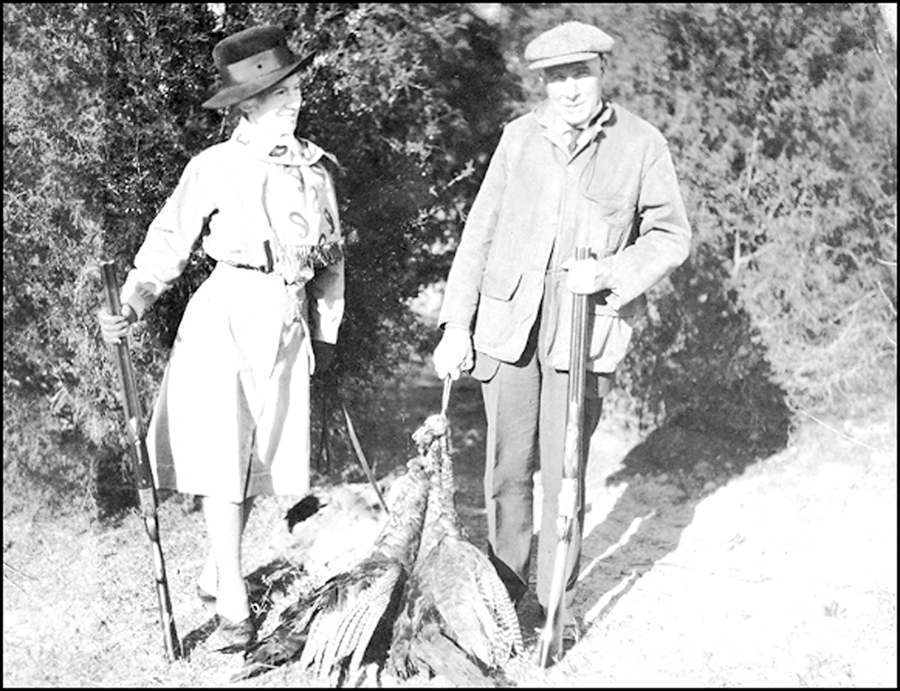

Now that the restoration is complete, guests are treated to a glimpse of life between the Gilded Age of the late 1800s and the Great Depression beginning in 1929 — a time when the wealthy and arts-minded mingled over golf in Pinehurst and horses in Southern Pines. A time when, historians suggest, fine tradesmen were lured to North Carolina to build Biltmore House in Asheville, and stayed on to adorn mansions throughout the state.

However, according to Donald Naysmith’s beliefs, things are just things and a house, even Duncraig Manor, is a temporary dwelling:

“It’s what is beyond that matters,” he states with conviction. “We have no permanent home down here. That is our guiding principle.” PS