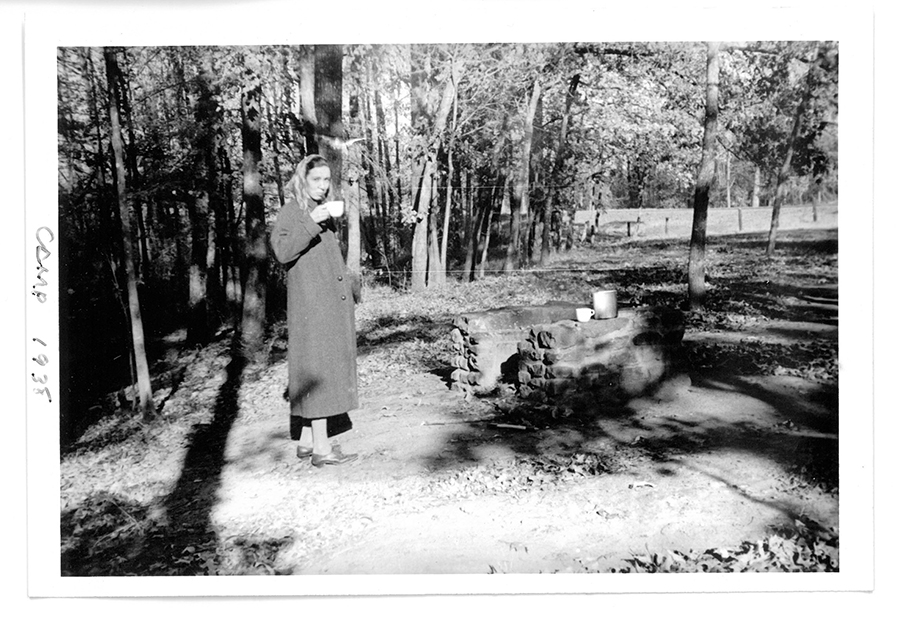

Small Town Life

A little piece of paradise

By Tom Bryant

The Old Man always used to say that a smart feller knew when he was well off and was a goldarned fool to change it for something he didn’t know about. — Robert Ruark from The Old Man and the Boy

Back in the day, John Mills and I didn’t know we had it so wonderful growing up in Pinebluff. Mr. Eutice Mills, Johnny’s dad, was mayor from 1952 until 1956, and the little village never had it so good.

I recently spent the day with my old friend Johnny, better known by locals in the know as the Pinebluff historian. As boys my home was about a block from his on the same road that we called the “lake road.” It was really New England Avenue. That’s a funny thing about Pinebluff. Most of the avenues are named after Northern cities like Boston, Philadelphia or Chicago, I guess to sort of entice the folks from up North who wanted to relocate to the sunny South. They could do that and still live on an avenue that reminded them of home.

The cross streets are named after a fruit of some sort, like peach, cherry or apple. Yep, Pinebluff in its early planning was aimed at making new residents feel right at home and comfortable.

As a youngster living a block from the Mills family, I got to know them pretty well, as they did me and my family. It was like that all over town. Everybody knew everybody, and their pets’ names. We didn’t have a downtown, just a service station on one corner of the main thoroughfare and a motel across the street. The post office was located on another block, and that was about it as far as the business district was concerned.

The little village didn’t have much commercial success, but for the residents, it was enough. Aberdeen was right down the road. That’s where we went to school and our parents did most of their shopping. Beyond that was Southern Pines, a slightly more sophisticated town. And a little farther down the road was Pinehurst, a location most of us gave no thought to. We knew that it was a destination for rich folks from the North who came to spend part of the winter, play golf and do whatever we thought rich folks did when they came south. It really was of no consequence to us, and we just let that part of our county alone.

In those early years when Johnny and I came along, Pinebluff had a population of maybe 300 residents, a little more if you counted the dogs. Not many families had television. I think I was a freshman in high school when my dad bought our first one. Most of our entertainment was what we could devise, and mostly it took place in the great outdoors.

Every kid had a bicycle, our main mode of transportation. Mine was usually leaning against the front porch of our house, ready for a quick getaway.

In the summer the lake was the destination for all the young folks, and that’s where I learned to swim. It was only five blocks from my house, all downhill. I could jump off our front porch, hop on my bike, push off and coast all the way to the lake without pedaling once. Getting back home was a different story. Usually, I would time it so Dad could pick me up, load the bike in the back of the station wagon and give me a lift to the house. Sometimes this worked, depending on how busy he was at the ice plant. In the summer when peaches were being harvested full blast, Dad hardly had time to come home for lunch. Then I had to muscle my bike back up the hill on my own.

Our telephone system was Mom and Pop Wallace. The Pinebluff phone company was at their house, and the switchboard was located in their living room. When our parents wanted to find out where most of their kids were hanging out, they’d give Mom Wallace a call. She usually had the scoop on what was going on in the neighborhood.

When Johnny and I met that day, we reminisced about old times until lunch and then decided to grab a bite at a new restaurant in Aberdeen. On the way back to Pinebluff, we rode by the Aberdeen Railroad Depot, where Harriet Sloan maintains the Aberdeen High School Museum that’s located in one end of the ancient building. It’s amazing the job she has done accumulating all the historical information and artifacts about a school that no longer exists. The depot was closed but we’d already seen it several times, so we drove on by and headed back to Johnny’s house.

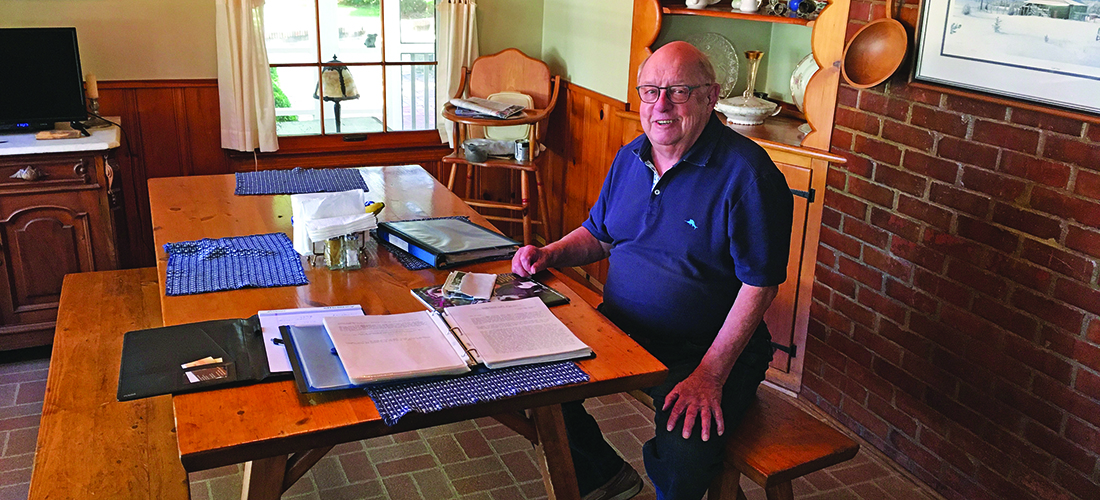

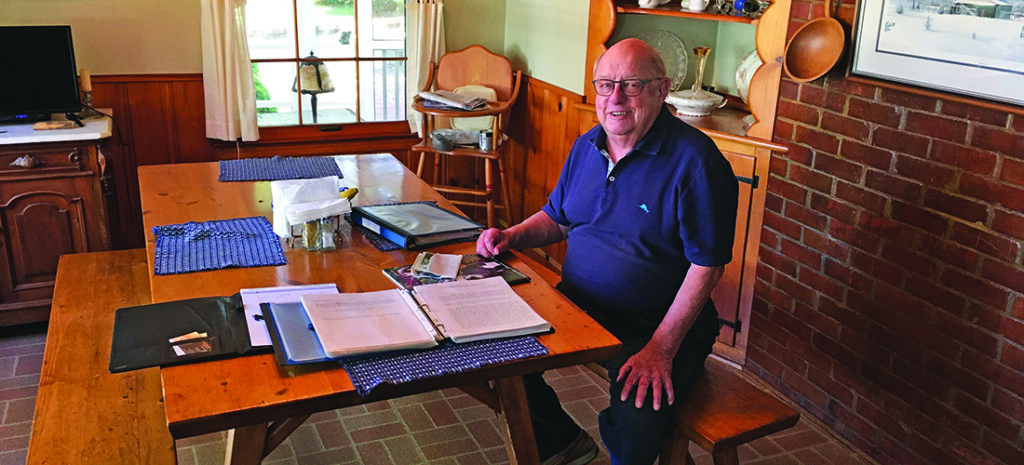

Johnny is fortunate to have acquired his family home place, and little has changed since we kids used to eat lunch sitting at the Mills’ kitchen table. Mrs. Mills would fix us sandwiches and listen as we made plans for the rest of the day.

Today was déjà vu all over again as Johnny and I relaxed around the same table remembering Pinebluff as it used to be under the direction of his father, the mayor.

“Think about the folks who used to live here,” he said, and began running down a list of people, some of whom I had forgotten.

“Colonel Cleary. Remember he lived right on the corner with his two boys? He taught math at Aberdeen High. And there was Mrs. Townsend, your neighbor. She was a traveling editor for The Christian Science Monitor. It’s rumored she roamed the world on tramp steamer ships.

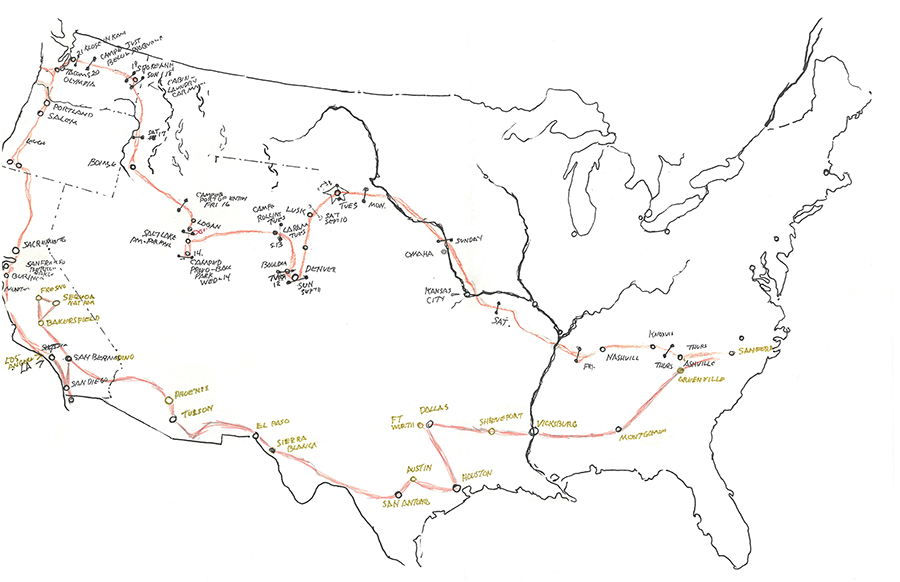

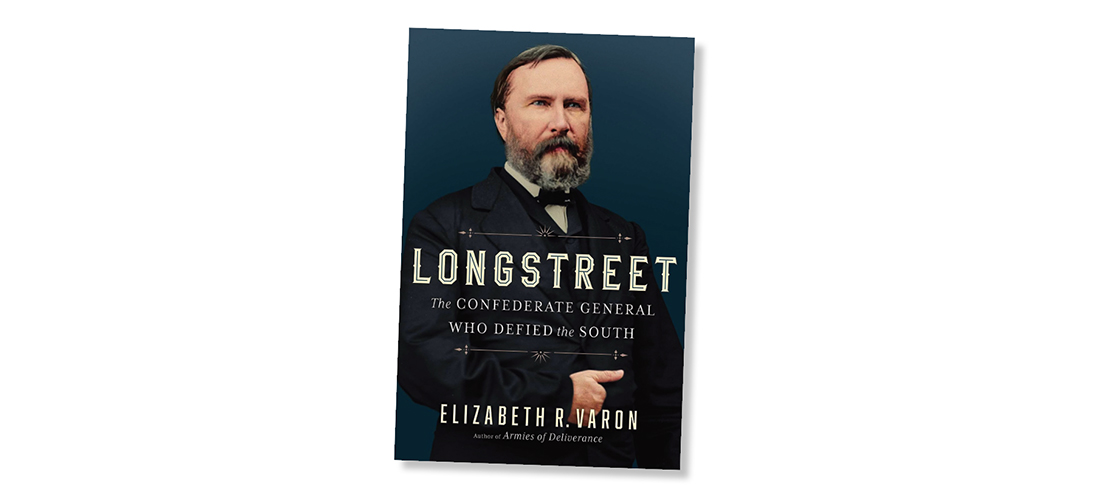

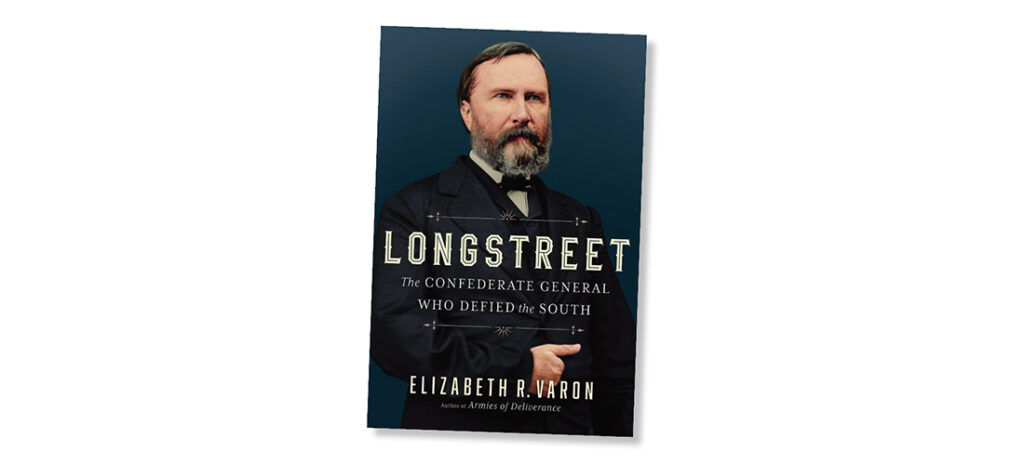

“Around the corner and a couple of blocks away was Manly Wade Wellman. A famous author, he wrote the book, The Haunts of Drowning Creek. We should surely remember that because it was about two boys who set out on a canoe trip on the creek to find Confederate gold.” (Maybe the book gave three young Pinebluff boys the idea to take the same trip and float to the ocean. But that’s another story.)

“And there was Glen Rounds, another famous author and illustrator. He lived here for a while before moving to Southern Pines. The village was loaded with famous people in those days, not counting us, of course.” We chuckled a little as Johnny continued to pay homage to past residents who had had such an impact on our lives.

“Mr. Deaton, the town constable. He looked after all the young people and kept us out of trouble. Dot and Nan Brawley, who owned and ran the Village Grocery. How many cold Cokes did we drink from her cooler? Of course, Mom and Pop Wallace and the phone company, and that’s just a few of the folks who made the little town work. Yep, Tom, we grew up in a fantastic place.”

As I sat there at the same kitchen table where I had rested so many years ago, I thought that it’s good that some important things don’t change with age, like this wonderful home and my good friend Johnny Mills. PS

Tom Bryant, a Southern Pines resident, is a lifelong outdoorsman and PineStraw’s Sporting Life columnist.

January is a sacred pause, a rite of passage, a miracle in the dark.

January is a sacred pause, a rite of passage, a miracle in the dark.  A birth flower of January, the snowdrop’s Latin name translates as “milk flower.” Emerging from a cold and sleeping Earth, the delicate flowers are, in fact, sustenance for the winter-weary, symbolizing purity, hope and new beginnings.

A birth flower of January, the snowdrop’s Latin name translates as “milk flower.” Emerging from a cold and sleeping Earth, the delicate flowers are, in fact, sustenance for the winter-weary, symbolizing purity, hope and new beginnings.