Cowboy Junket

Selling books like snake oil

Or

If you want it done right, do it yourself

By Stephen E. Smith

Nancy Rawlinson was a first-grader at Millington Elementary School in New Jersey when she happened upon an intriguing book in the school library. She flipped through the pages and immediately fell in love with the illustrations of horses. The book may have been The Blind Colt or Stolen Pony or Wild Horses of the Red Desert — she has forgotten the title — but she knew what she liked, and that the artist was Glen Rounds. “I was in love with horses at the time,” she recalls, “and I read Glen Rounds’ books over and over again.”

In 1991 Rawlinson moved to Southern Pines and eventually opened Eye Candy Gallery & Framing on Broad Street, but she never had an opportunity to meet the writer and illustrator whose books had brought her so much pleasure in her childhood. Rounds (the appellation assigned to Glen by his many friends) lived almost half his life in Southern Pines, and he was affectionately acknowledged by acquaintances and neighbors as “the literary man about town.” Decked out in his weathered jeans and cowboy vest, he was the craggy, gray-bearded bohemian wandering among the business-clad locals and Yankee snowbirds — a mid-morning regular at the local post office, where he’d buttonhole friends and strangers and regale them with humorous, wisdom-laced tall tales, droll shaggy-dog stories, and the occasional off-color witticism.

If Rounds was a raconteur extraordinaire, he was, first and foremost, an artist/illustrator. He illustrated over 100 books. He studied painting and drawing at the Kansas City Art Institute and the Art Student League of New York, and was close friends with Jackson Pollock and Thomas Hart Benton. (Rounds and Pollock were models for Benton’s painting The Ballad of the Jealous Lover of Lone Green Valley.) And he worked with dogged determination to see that the public could enjoy his talents. When Rounds published a new children’s book, it would garner a mention in Time or Newsweek, and 20 years after his death, his artwork lives on in his books and on the walls of homes and businesses in Southern Pines — and across the country.

Of all the stories Rounds shared with friends and strangers, there’s one that seldom, if ever, got told: the true story “that needed telling.” Shortly before he died in 2002 at the age of 96, Rounds informed friends that he had a new book underway, the story of the “1938 Trip West.” He never completed the book, but his extensive notes were passed down to his daughter-in-law, Victoria Rounds, and contained within the extensive scribblings are at least four synopses that retell the tale in fits and starts. The Gospel according to Rounds goes as follows:

During the spring and summer of 1938, Rounds was carrying on an “acrimonious” correspondence with Vernon Ives, the publisher and editor of Holiday House, concerning Holiday House’s lackadaisical sales efforts. The publisher had a few independent salesmen who carried Holiday House books as a sideline and they circulated a catalog, but there was no sales coverage west of the Mississippi.

“I had spent some time with folks selling snake oil, Indian remedies and the like,” Rounds writes. “And argued that if they wanted to sell books they should have somebody on the road stirring things up. In the end it came to a case of ‘put up or shut up.’ If I thought books could be sold like snake oil, why didn’t I go on the road myself and show them how it should be done?”

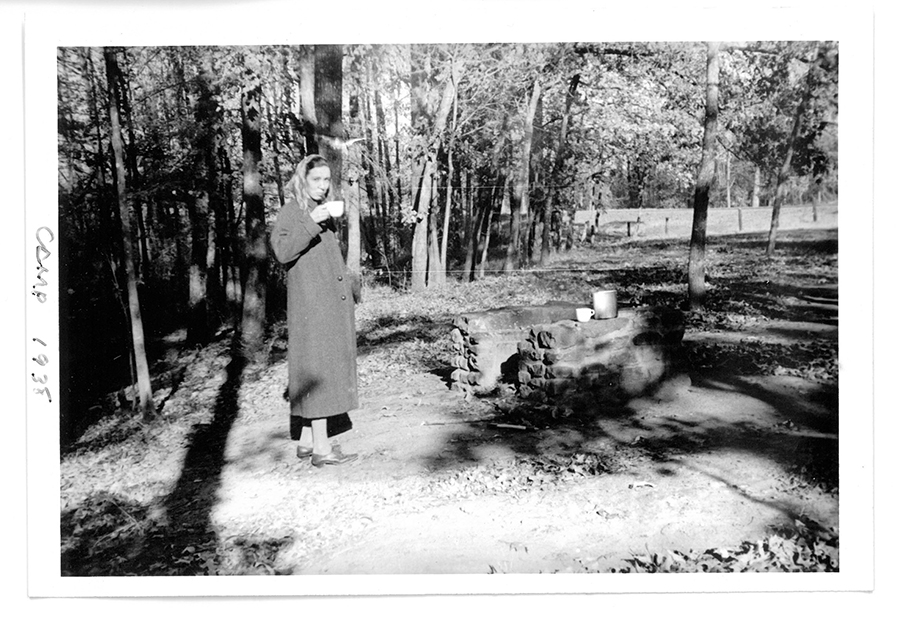

And that’s exactly what Rounds intended to do. He and Margaret Olmsted had married in June 1938, and they were living in Myrtle Beach, where they paid $10 a month in rent. In their spare time, they fixed up a 1937 Studebaker woody station wagon with bunks built over lockers that contained their camping equipment — a bucket, a pan, a coffeepot, blankets, clothes, a Coleman stove, a small icebox, and a canvas to throw over the back of the Studebaker at night.

On September 1, 1938, they loaded a box of Holiday House books into the Studebaker and headed west from Sanford, camping that night in a “nameless field between Knoxville and Nashville.” There were no motels in those days, but they occasionally pulled into a campground or hotel to wash clothes and shower; otherwise, they quit driving each day at sunset and made the best of their surroundings. Once they camped near a city dump, and on another evening, a constable directed them to park behind the town bandstand. “Nice little park,” Rounds recalled. “Just after supper people started drifting into the park. It was band concert night, and while they waited for the concert to start the townspeople inspected and commented on our outfit.”

But Rounds and Margaret weren’t there for the music, and they weren’t on a sightseeing trip. They had compiled a card file listing every elementary school, library, branch library, librarian and bookstore on their route. Margaret had a library science degree from the University of North Carolina and had worked for the New York Public Library System, so she had credibility with the school librarians and teachers. “We were looking for people who dealt in books,” Rounds writes. “Anybody that ever looked like they might buy or sell books got the treatment. We stopped at every small branch library or school, showed books, told a story or drew some pictures and went on, leaving Holiday House catalogs behind.”

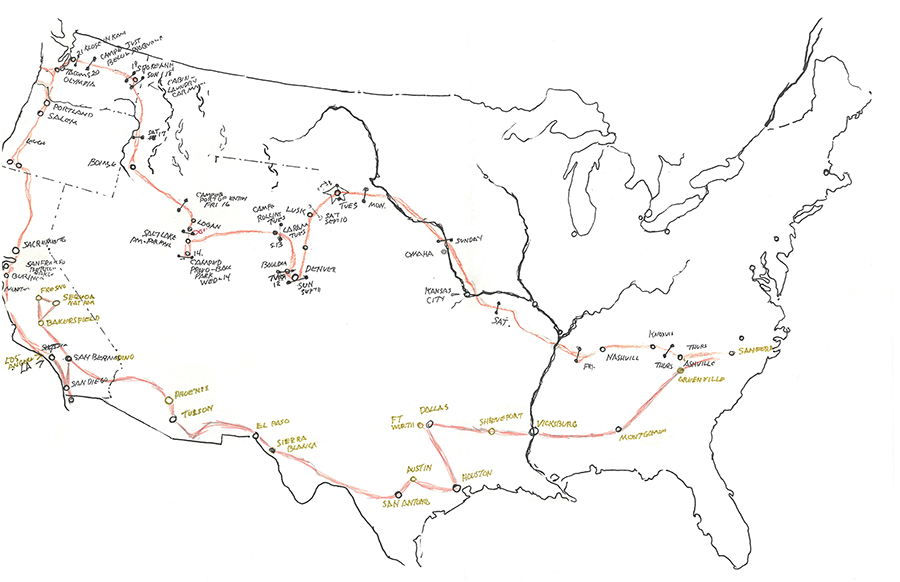

And so it went through Kansas City, Omaha, Sioux City, Rapid City, Denver, Boulder, Provo, Logan, Boise, Spokane, Seattle, Tacoma, Olympia, Portland, Salem, Medford, Sacramento, San Francisco, Fresno, Los Angeles, San Diego, Phoenix, Tucson, El Paso, Sierra Blanca, San Antonio, Houston and Dallas/Fort Worth, where they put on a “big show” for National Book Week. From there they hit Shreveport, Vicksburg, Montgomery, Atlanta, Greenville, and back to Sanford, arriving on Thanksgiving eve after three months on the road and “tired as hell!”

“We not only showed the Holiday House books but we sold them on commission,” Rounds writes. “Whether we sold enough to pay our gas and expenses, I don’t remember. But by the time we got home a hell of a lot of people had heard about Holiday House books. For years after that, stories about our unconventional selling methods drifted around the country whenever bookstore people and librarians met.”

In the synopses Rounds produced late in life — probably in the late ’80s and early- to mid-’90s, judging by the used computer paper repurposed as cost-effective stationery — the story lacks the details of meetings and confabs Rounds and Margaret experienced. But those moments aren’t lost. As Rounds traveled the country and pitched Holiday House books, he regularly wrote to Vernon Ives, producing 24 lengthy handwritten letters detailing most of his encounters with teachers, administrators, bookstore folk and “anyone interested in books.” Ives saved and returned the letters to Rounds, who arranged them chronologically in a spiral notebook that also contains photographs, maps, two traffic tickets, two typhoid inoculation certificates, and Rounds’ meticulous financial calculations (the Studebaker got about 22 mpg in a great loop from Sanford, North Carolina to the West Coast and back to Sierra Blanca, Texas, a distance of 8,633 miles).

More than an illustrator and writer, Rounds was a keen observer of his fellow human beings — he had a caustic word or two to say about everyone he encountered — and he was especially sharp-eyed when observing the animals he drew. Former North Carolina Poet Laureate Shelby Stephenson once accompanied Rounds on an expedition to observe a family of beavers. “Glen just sat there for two hours and never said a word; never moved,” Stephenson recalled. “He was perfectly still, staring intently at the beavers, never missing a movement they made.” If he wrangled you into a storytelling marathon at the post office or in his side yard on Ridge Street, he’d stare directly into your eyes as his story leisurely unraveled. If your mind happened to wander, he’d notice immediately. “Do you want to hear this story or not?” he’d ask. Of course, you wanted to hear it. There was no escape.

This innate ability to study and narrate is apparent in a beautifully crafted excerpt from a letter written to Ives shortly before the 1938 odyssey. Rounds had been observing those who labored in tobacco production, “one of the last of the really personal industries,” and highlights of the brief passage stand as an example of literary archaeology:

“From the time they go out in the spring with leaf mounds to fill the seed beds, the setting out, which is done by hand, the hoeing, the worming, down to the beginning of ‘priming’ (picking the bottom leaves as they ripen), and the sitting up night and day with the fires in the curing barns, it is all handwork of the hottest kind for the whole family. After it’s cured, the whole family gets busy, usually on the front porch, and goes over it leaf by leaf, grading it before tying it into ‘hands’ for market. The night before market they start coming into the warehouse to get a good position on the floor so as to get a light that will set off the color and texture to the best advantage. They’re proud of their work. Sat all afternoon a while back with an old-timer while he watched his fires. After I’d deserted my cigarettes for a healthy chaw of his Honey-twist, taken with a fine shaving of Black Maria to give it body and color to spit a more satisfying brown, we sat and spit promiscuously round about for a while, exchanged views on horse breeding, and the lack of enterprise and self-reliance in the younger generation and one thing and another . . .” and so forth for two single-spaced typewritten pages.

The 24 letters written to Ives don’t contain the same level of detail as his tobacco observations — there wasn’t enough time to include more than initial impressions — but Rounds’ sharp eye picked up every human shortcoming and attribute, every nuance.

On Sept.12, he wrote from Denver: “Enclosed an order from Dibamels (sic), Rapid City. Think if we can get him started he should move my books. Did some horse trading to get the order, but think it worth it, even if I had to take merchandise for 3 Ol’ Pauls and 3 L.C. Denver Dry Goods no soap. Books too high. Kendrik Bellamy was nice dept, but in basement, Mrs. Cook very nice and liked books but has trouble moving good books. However, may order later.”

On Sept. 15 he wrote from Salt Lake City: “Library (two old maids) no soap. No children librarian. Printed Page, nice shop, typical university bookshop. Trying to start juvenile dept but knows nothing and cares less. N.G. (no good) . . . Snow and sleet in the passes. Ranger stopping cars . . . camping in ballpark . . . Utah Office supply already ordered Baker Taylor, cheap stuff, won’t see sample. High school library — Miss Robinson liked books and checked a number. No money for about 60 days but . . . Ferner Junior High School, Miss Sinor — tough old gal. Doesn’t like small type. Won’t order what she hasn’t seen . . .” And so it goes for seven handwritten pages, passing judgment on the people, libraries and schools in one lengthy intensive missive.

Even more detailed letters follow from Spokane, Seattle and Raywood, where Rounds reports that all the bookstores had gone out of business during the Great Depression. Books are a tough sell, especially during hard times, but Rounds and Margaret remained undeterred by the occasional rejection and were much buoyed by small successes, as in San Diego on Oct. 24: “City Schools, Miss Morgan — They hadn’t seen our books but had heard so much they finally ordered most of the old titles for review. However, they arrived too late to get on this year’s list, L.C. and Ol’ Paul got raves from their reviewers. And most of the others seemed slated for the list also. She should be on list for books ON APPROVAL as soon as they are published . . .”

In Seattle, Rounds and Margaret made 12 stops and in Denver another 11, talking up Holiday House and pitching Rounds’ books while visiting public libraries, a university bookstore, the state department of education, a school library association and a book department in a general merchandise store, etc. — all of which he reported on at length. But Rounds’ letters weren’t all business. While working a bookstore in San Leon, Texas, he couldn’t pass up an opportunity to describe a fetching female clerk: “She was like a mare in heat every time she sidled close and continually ran her palms of her hands over the front of her tight sweater, down the belly and back around her buttocks. You know the gesture? It is used with the flexing of all the trunk and thigh muscles. Don’t get me wrong — I just report what I see. She’ll make a fine type if I write a book.”

If there was rejection and indifference, there was just enough good news to keep Rounds buoyant. On Nov. 19 he wrote to Ives, alluding to himself in the third person: “Rounds at his best when before an admiring audience of children whose number will be considerably swelled by the attendance of a group of storytelling teachers or some damn thing, who have a special invitation. Immediately after Rounds is worn out, there will be an autograph party in the book department.”

And so it went, stop after stop, for three relentless months, each encounter explicated in the lengthy handwritten letters to Ives. If Rounds and Margaret encountered more failure than success, they never wavered, never despaired. They kept at it, day in and day out, until they pulled into Sanford, exhausted.

Small successes, what he thought of as a “little victory for art,” continued to fuel Rounds’ enthusiasm for the remainder of his long life. He frequently visited classes full of elementary school students, encouraging their art and following up by sending the students postcards with his trademark hound dog Ol’ Boomer, tail curved skyward, prancing into the mystical ether. He never tired of entertaining, never grew weary of inspiring a classroom full of blossoming talent.

If Rounds was the author and illustrator of the books, Margaret Olmsted was remarkable in her own right. Glen Rounds was born in a sod house near the badlands of South Dakota and traveled in a covered wagon to Montana, where he grew up on a ranch. Margaret came from money. Her family owned their own railway car, and she’d graduated from the University of North Carolina. Nevertheless, she endured three months of camping across the country and chatting up librarians, schoolteachers and classrooms full of rowdy children, all without complaint. She was one of the founding members of The Country Bookshop and the Given Memorial Library, and her considerable influence lives on in those Sandhills institutions — and in Rounds’ success as a writer and illustrator.

What were the results of the 1938 trip? In a time when writers didn’t often appear at bookstores to sign and sell books, Rounds was ever present, signing his name, telling his stories and promoting Holiday House. Vernon Ives profited from the documentation Rounds supplied concerning likely outlets and agreeable bookstore owners, information that would hold the publisher in good stead for decades to come. And most importantly, Rounds made himself famous in the world of children’s literature. His books still line bookstore and library shelves and continue to delight young readers.

Not long after his passing, an ad hoc committee of Rounds’ friends convened to consider placing a lifelike statue of the old raconteur in front of the post office, a monument not unlike the one of the rock ’n’ roll dude “standing on a corner in Winslow, Arizona . . .” but it soon became apparent that such a tribute could never adequately convey Rounds’ charisma and rakish charm. The stories were gone, lost for good, and now Rounds exists only in the memory of his many admirers.

It’s doubtful that Glen Rounds ever visited an elementary school in Millington, New Jersey — a village so obscure that it seems hardly to exist on the map — but when first-grader Nancy Rawlinson fell in love with Rounds’ drawings of horses, the book had not found its place on the library shelf by accident. Glen and Margaret Rounds had, by virtue of their hard work, tenacity and unwavering faith, willed it there. PS

Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of seven books of poetry and prose. He’s the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press Awards.