A Love Affair

Payne and Pinehurst

By Lee Pace

Another U.S. Open in the offing.

And this one just so happens to roll around one neat quarter-century after one of the most famous strokes in Open history — Payne Stewart’s 20-foot putt on the final green to edge Phil Mickelson by a shot in June 1999. Three months later, Stewart was gone, the victim of a mysterious airplane malfunction that took his life and five others on a planned flight from Orlando to Dallas.

The “Payne Pose” statue sits today by the 18th green of No. 2 and is the most photographed visual in Moore County. Stewart’s spirit remains strong in other corners of town, among them at the Pine Crest Inn.

Stewart was just out of Southern Methodist University in the summer of 1979 and was preparing to compete for his PGA Tour playing privileges in the tour’s twice-a-year Qualifying School, the next one to be held in November at Waterwood National Country Club near Houston. He traveled to Pinehurst in mid-September to enter a series of four mini-tour events run by the National Golfers Association. Seventy-two hole tournaments were scheduled for Whispering Pines, Seven Lakes, Pinehurst No. 4 and Hyland Hills. The players put up their own money and competed for purses between $30,000 and $40,000 per tournament. A handful of players stayed at the Pine Crest Inn, where proprietor Bob Barrett gave them a generous price on room and board.

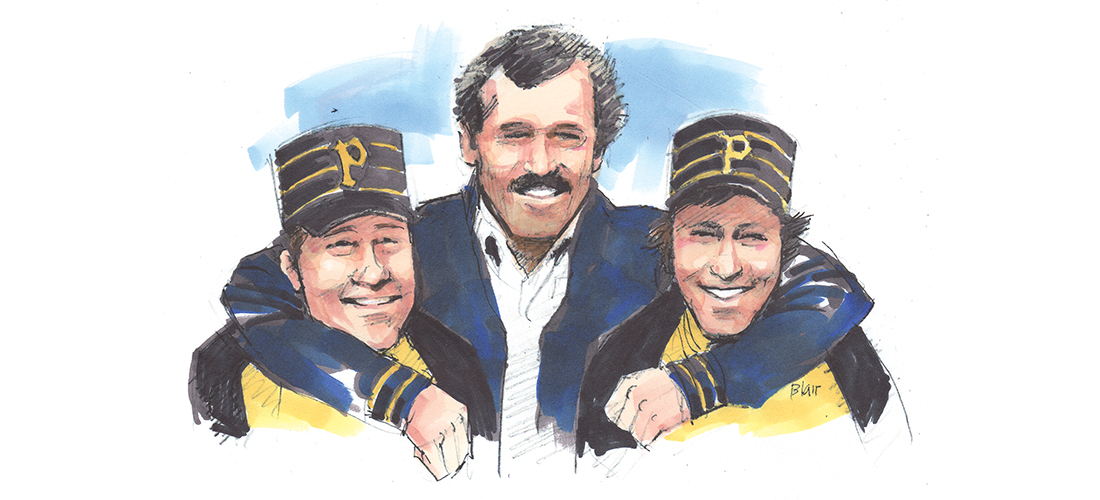

“It was like golf camp for a month,” remembers Peter Barrett, one of Bob’s two sons. “Payne was the funny guy of the bunch. He had control of the whole group. There were a lot of different personalities there. They were on a mission. They all had their eyes on the big-time, and they were playing with their own money. They were pretty serious, but they still had some fun.”

After the four tournaments — two won by Scott Hoch, one by Kenny Knox and one by Mike Glennon — Stewart packed up his car and was saying goodbye to Barrett in the parking lot. There he offered a marketing deal to Barrett: Stewart would put the Pine Crest’s name and logo on his bag for $500 a year. Barrett said he’d pass. Stewart had talked about a potential trip to Asia if he didn’t get through the upcoming Tour Q-School (he did, in fact, miss qualifying and go to Asia), and Barrett didn’t figure the Pine Crest needed exposure in the Far East. And $500 in 1979 was a lot of money.

“What an investment that would have been, huh?” Barrett says ruefully.

Stewart became smitten that fall with the personality of the Pine Crest, its homey feel and the ebullience of “Mr. B’s Old South Bar,” a renowned watering hole. Whenever the PGA Tour returned to Pinehurst over the years — for the Hall of Fame Classics in the early 1980s or the Tour Championships of the early 1990s — Stewart returned to the Pine Crest, if not to bed down at least to eat and drink. In the early 1990s, he negotiated his NFL clothing deal over dinner in the Crystal Room, an adjunct of the main dining room. He sang and hung out with his buddies and bet on NFL football in the bar. He also ate a lot of banana cream pie. Marie Hartsell, a cook in the inn’s kitchen for some 35 years until her retirement in 2010, prepared one of the inn’s signature desserts, and whenever Stewart visited over the years, he’d dive into a banana cream pie.

“He’d eat a whole pie by himself,” says Barrett.

Stewart rented a house on Pinehurst No. 6 during the 1999 Open but visited the Pine Crest early in the week to see his old friends. He signed his name in huge script letters on the wallpaper of the men’s rest room (an iteration of that signature is framed and hangs in the lobby today). Stewart also told Barrett he was playing quite well.

“Pete, I think I can win this thing,” he said.

Stewart spent a few minutes that evening talking to Patrick Barrett, the 9-year-old son of Bob Barrett Jr., also a son of the longtime owner of the inn. Patrick had shrugged off his introduction to golf two years earlier, primarily because it had been forced upon him by his grandfather. But now that the youngster was making his own connection to the game, golf seemed like something that might be fun to pursue. Stewart made quite an impression.

“They connected because Payne sat down, looked Patrick in the eye and made him feel special,” says Andy Hofmann, the boy’s mother. “Patrick spent the entire Open week following Stewart.”

Patrick is now 34 years old. After graduating from the University of North Carolina and playing on the Tar Heel golf team, he entered medical school and today is a surgical resident at a hospital in Seattle. Like all of us who were there somewhere along the 18th hole on June 20, 1999, he marvels that blink — 25 years are gone.

“Grandpa knew a lot of players,” Patrick says. “He knew them before they were famous because they’d stayed at the Pine Crest. The only golfers I knew then were Tiger Woods and Jack Nicklaus. He called Payne over and introduced me. Grandpa said, ‘This guy is going to win it.’ Payne shrugged it off and said good to meet you, made a fuss over me. It was kind of embarrassing thinking back on it. I didn’t even stand up.

“He signed a piece of paper for me. It said, ‘To Patrick, keep swinging, Payne Stewart.’ I’ve got that piece of paper somewhere. Now all of a sudden golf was cool. My mom gave me lunch money and turned me loose every day that week.

“I was so short, I couldn’t see much of the action, but I could feel the energy. I was more interested in autographs and celebrities than the golf. But that week I decided I wanted to play golf, to learn the game. I was absolutely golf-obsessed from then on out. I started to play with a real purpose.”

The dominoes fell that week for Stewart. He was a “feel player” competing on a golf course that rewarded right-brained tendencies. He’d missed the cut at Memphis the week before and got to Pinehurst five days early to map out his game plan. He was playing clubs and a ball suited to his skills after a half-decade of chasing endorsements with ill-fitted implements. He had matured from his younger, petulant ways, losing on the final day of the Open at the Olympic Club in 1998 with grace and composure.

And Stewart was confident and comfortable in Pinehurst.

He made eye contact and smiled at the locals in the grocery store. He joked with the ladies at check-in on Sunday when asking for scissors to cut off the sleeves of his rain jacket (starting a new fashion trend, by the way). He had a heartfelt reunion with old friend and instructor Harvie Ward before he took off for the final round in his navy plus-fours, red/navy striped shirt, navy tam, and white socks and shoes.

“I think it’s safe to say I love Pinehurst,” Stewart said when it was over. “This is a special place. It was a perfect way to win. I think everyone in the field will attest to how great No. 2 is and what a special place this is. To win here means a lot to me. This place is a gem. It’s beautiful. It’s phenomenal. We never see a golf course like this on the tour. It’s a refreshing change of pace.”

Needless to say, the echoes from ’99 will reverberate through the pines over the coming months. PS

Author Lee Pace chronicled Payne Stewart’s magical week in 1999 in his book The Spirit of Pinehurst, published in 2004.