Southwords

“I See Great Things in Baseball”

The boys of spring, summer and fall

The first time I saw Jim “Catfish” Hunter up close was during spring training in the late ’70s. The New York Yankees, who trained in Fort Lauderdale, were playing the Pittsburgh Pirates, who called Bradenton their winter home. We drove south all night and managed to get to Florida in time to see a game — we didn’t care which one, we were on vacation. I believe, though I can’t swear to it, that this was the year my wife, the War Department, who was educated at a fine Midwestern university famous for its engineers and astronauts, looked around the stands at the great number of people wearing black baseball caps with a gold ‘P’ on them and said, “This must be some kind of Purdue alumni society.” Of course, she hadn’t slept in 24 hours.

Anyway, we saw Hunter outside the ballpark. Like us, he was just arriving. Fueled by caffeine, we were wearing T-shirts and sunscreen. He was wearing a powder blue leisure suit and the easygoing demeanor of a man who would be spending the day lounging in the bullpen. Catfish was looking stylish — I said it was the ’70s, right? — but he had nothing on Willie Stargell, who was often seen driving around Bradenton in his Rolls-Royce.

For those who don’t remember Hunter, he won 224 games in his Hall of Fame pitching career for the A’s and the Yankees. He was an eight-time All Star and pitched for five World Series champions. Though it was Curt Flood who led the charge to overturn baseball’s reserve clause (it finally happened in 1975), Hunter became the game’s first million-dollar free agent when Charles O. Finley, owner of the A’s, failed to live up to the terms of Hunter’s contract. It was Finley who, after drafting the promising prospect from the bucolic eastern outposts of North Carolina, decided the young man with a bum foot needed a nickname. How he lit on Catfish, I have no idea. Hunter, weakened by diabetes and plagued by arm trouble, retired at the end of the ’79 season at the age of 33. He remains the last pitcher in Major League baseball to throw 30 complete games in a season. Twenty years after hanging ’em up, he died at age 53 of Lou Gehrig’s disease.

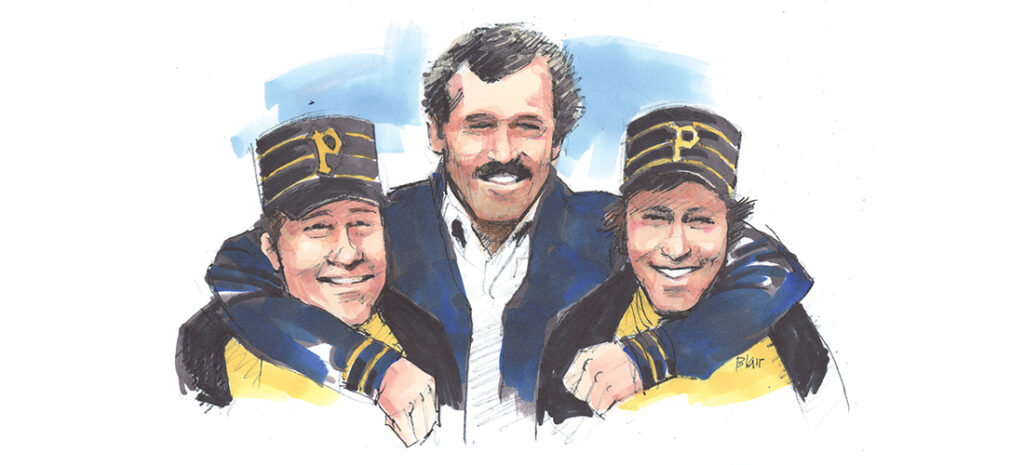

The next, and last, time I saw Hunter up close was when I was sent to his home in Hertford, North Carolina — where everyone knew him only as Jimmy — to take his photograph along with his son, Todd, and his brother, Peter. Todd was 14 years old and hitting .444 for the Pirates of Perquimans County High School. Peter was the team’s coach. He was also, incidentally, the brother involved in the hunting accident that cost Jim a toe and embedded buckshot in his right foot.

Jimmy was 39, plus or minus, the day I showed up to take his picture. His most recent appearance on the mound had been in a Perquimans alumni game, where he hung a curve ball that Todd pulled down the left field line for a double. The next batter homered. Catfish did have a knack for giving up the long ball.

While Peter and I waited for Jimmy to join us for the photo shoot — it was a working farm and he was on a tractor plowing the fields behind his house — Peter was throwing a little batting practice for Catfish’s youngest son, Paul, who was maybe 6 at the time. Make no mistake, athletic genes are real. Peter would throw the ball (a regulation baseball) underhand to Paul, who kept hitting frozen ropes right back through the box. Bam. Bam. Bam. When Jimmy finally arrived, he watched his son’s hitting exhibition for a few moments in silence, then looked at his brother and said, “Throw it overhand.” With that, he went inside to clean up.

After taking a couple of photos, one with Catfish and the two Pirates posed in front of a sign painted on the side of a barn that said “The Pride of Perquimans,” Jimmy invited the War Department (my assistant) and me into his house. The balusters supporting the railing going upstairs were made completely of baseball bats. More impressive was the silver replica of the World Series trophy on the table next to the stairs.

“Reggie Jackson had this made for me,” Jimmy said. It was by way of saying thanks. Mr. October telling a teammate that, if it wasn’t for him, they never would have gotten that far.

It may only be April, but fall is always in the air. PS

Jim Moriarty is the Editor of PineStraw and can be reached at jjmpinestraw@gmail.com.