Sporting Life

Heroes Among Us

Some quiet thoughts in the woods

By Tom Bryant

“They ask me, ‘What do you think about in the woods?’ I tell them all sorts of things, but actually I’m trying not to think of anything special at all.” — Gene Hill, A Listening Walk

Gene Hill, one of my favorite outdoor writers, once wrote, “The woods are where I go when I’m starved for quiet.” Easy to understand in today’s cacophony of noise in what we call civilization. Sometimes, for me, the urge to head to the woods is overwhelming. That’s when I grab my hunting bag, a dove stool, a couple of snacks and maybe a libation or two, and drive down to the little farm I lease for some restoration of my soul.

Like Hill, I try not to think about anything at all, but when I’m hunkered down in the stand of pines bordering the beaver pond, my mind just doesn’t stay still.

This last small-scale outing was different. Just as I was settling in, watching the pond, a pair of wood ducks splashed down right in front of me and swam to the far side. I don’t know why, but my mind cranked up like a runaway computer. With July coming, I started thinking about heroes. What the ducks had to do with that particular line of thinking, I don’t have a clue.

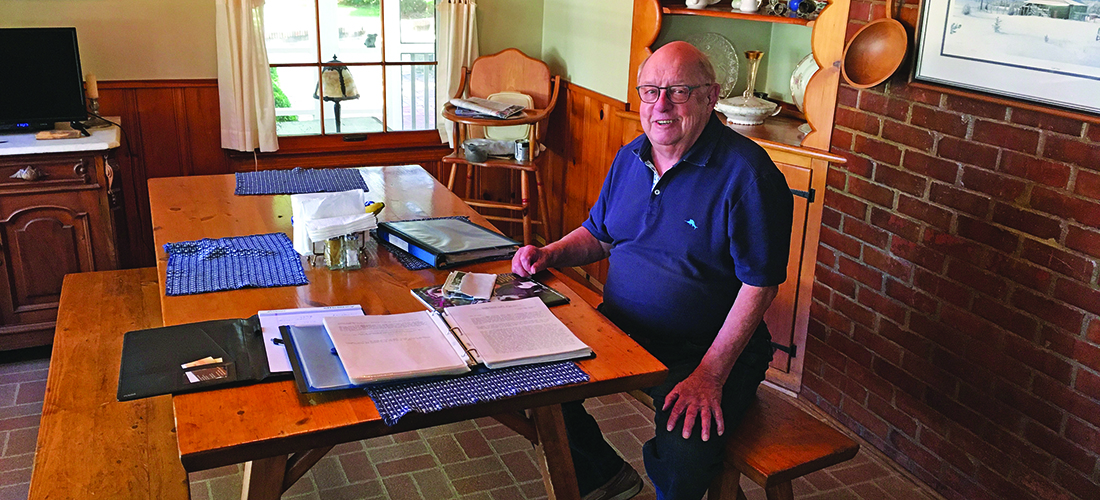

In my many years of watching and wondering, I’ve met numerous people I would place in the hero category. The most recent is Bill Berger, an interesting fellow I met at our breakfast club.

What I call our breakfast club is an assembly that meets at the Sizzlin’ Steak or Eggs restaurant at a table in the back, just right for a small party. A diverse gathering, this compact get-together would qualify in its own right for my list of heroes, but right now my mind was focused on Bill Berger.

Bill was born in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, home of the state’s first producing oil well, and it’s easy to see how he grew up in the oil business. His father was a major executive with the Phillips 66 Company, but according to Bill, it was not necessarily a good thing. The family moved quite a bit with his father’s responsibilities. Bill complained of living at one of the refineries when he was a youngster. “Naturally, Dad’s position with the company let us live in the largest, most ornate company house, but it was in the middle of the refinery’s tank storage area,” he says. “All I could see through our home’s windows were acres of gas holding tanks.”

Bill attended Oklahoma State University, where he met his lovely bride, Bonnie. They were married and after graduation, he entered law school at the University of Tulsa. Before finishing law school, as happened to quite a few young folks during that period of our history, he was drafted. He chose the Air Force and became a pilot flying a KC-135 refueling tanker plane.

After two tours in Vietnam, he mustered out of the Air Force and went back to law school. When I asked him about his experiences during the war, he merely replied, “Tom, let’s just say it was an interesting time.”

Bill finished law school, re-entered the Air Force and became a liaison officer to Congress. One of his duties included investigating military plane crashes.

He retired after 22 years of service, but not being the kind of guy to sit back in a rocker, he signed up as a consultant to the Federal Aviation Administration, where he accomplished such things as improving pilots’ working conditions in the cockpit, determining the best height for control towers, and helping to raise the mandatory retirement age for pilots from 60 to 65.

Bill and Bonnie live in Beacon Ridge. Their son, Scott, is a surgeon in Winston-Salem, and their daughter, Megan, is in the travel business in Wilmington.

Bill has never met a stranger and can talk to you with rapt attention, as if you were the most interesting person he’s ever met. He even drives a happy car — a canary yellow Corvette.

The wood ducks splashed up from the pond and flew right at me. A wonderful sight, but my brain was already in running gear, moving about as quickly as those ducks, and I scarcely paid attention.

So who’s next on my impromptu list of heroes? How about the other guys at the men’s fellowship breakfast?

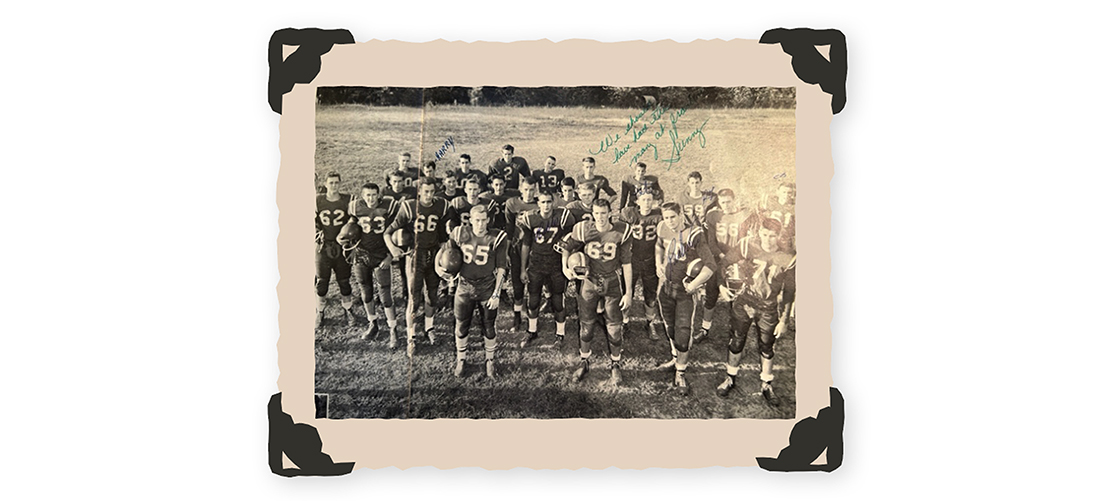

First there’s Bill Giles, a retired Presbyterian minister; then there’s Bill Dixon, a retired Air Force colonel; and Bill Hamel, a retired lawyer; and, of course, Bill Berger. A lot of Bills.

Next would be Fred Monroe, a retired construction contractor; Bob Harling, a retired oil man; Milton Sills, a retired educator; John Green, a retired teacher and coach; and me, a retired ad man and itinerant outdoor writer. If you combined all that time of living and experiences, you would have close to 800 years of practical knowledge and understanding of what makes the world go ’round, or so we would like to think.

As the sun slowly began its evening descent, a barred owl started calling from way back in the swamp. I could barely hear him. I picked up the dove stool, put my leftovers and trash in the pocket of the stool and headed back to the truck. I got to the field that the farmer had planted in corn. It was a little over knee-high, and the wind softly blowing across the newly planted stalks made sounds like ocean waves of a calm sea breaking on the beach.

I sat there for a bit watching another wonderful Carolina day come to an end and thought about Gene Hills’ quote from his book, A Listening Walk. I did more thinking today than listening on my impromptu visit to the beaver pond, but it did my heart good to realize that our country is full of heroes just like the ones I know in our neighborhood.

I cranked the truck just as the moon was coming up over the tree line. I felt good. My soul had been replenished. PS

Tom Bryant, a Southern Pines resident, is a lifelong outdoorsman and PineStraw’s Sporting Life columnist.