Omnivorous Reader

Civil War: Pastand Present

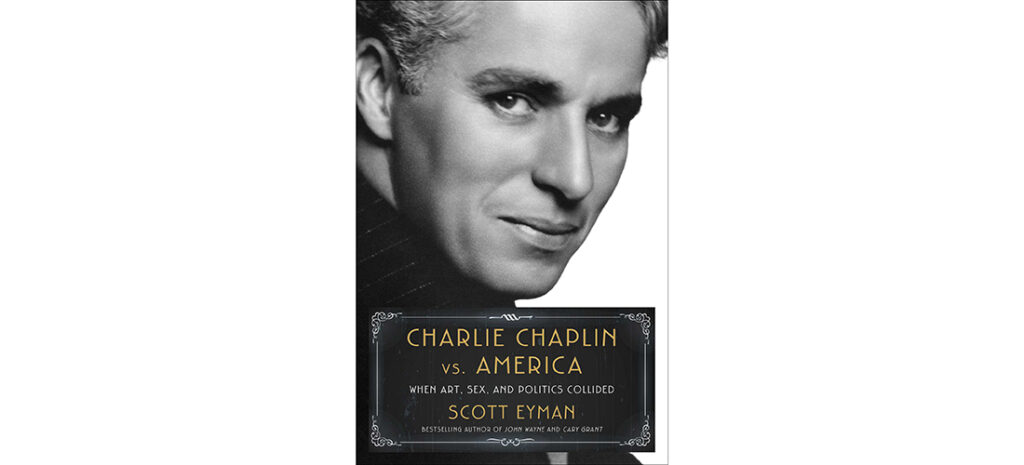

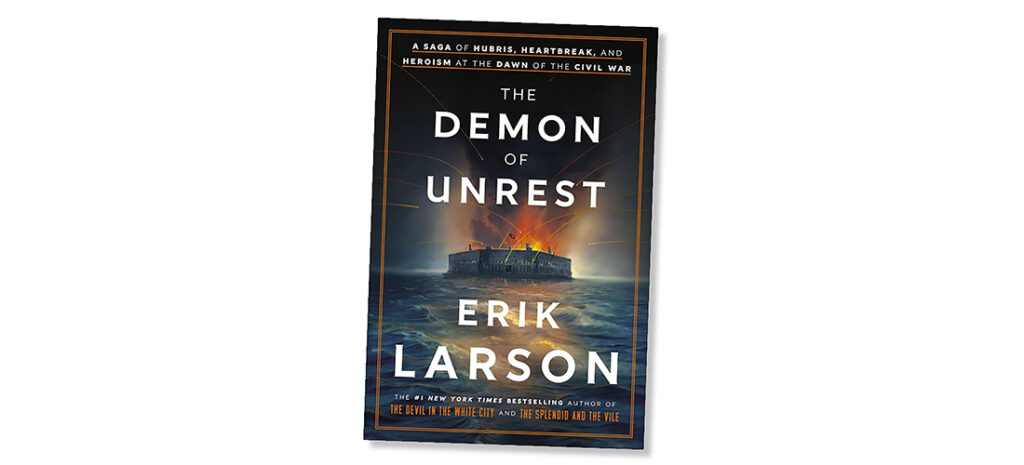

Erik Larson’s The Demon of Unrest

By Stephen E. Smith

Books about the American Civil War sell themselves. Publishers know there’s a loyal audience eager to buy reasonably well-researched volumes about the most tragic event in American history, and that’s enough to keep the bookstore shelves stuffed with warmed-over and newly discovered material. But how does a Civil War historian appeal to a broader audience? Simple: link the events explicated in his book to the present or, even better, to the future.

Erik Larson’s The Demon of Unrest: A Saga of Hubris, Heartbreak, and Heroism at the Dawn of the Civil War purports to do just that. Larson states in his introduction: “I was well into my research on the saga of Fort Sumter and the advent of the American Civil War when the events of January 6, 2021, took place. As I watched the Capitol assault unfold on camera, I had the eerie feeling that present and past had merged. It is unsettling that in 1861 two of the greatest moments of national dread centered on the certification of the Electoral College vote and the presidential inauguration. . . I suspect your sense of dread will be all the more pronounced in light of today’s political discord, which, incredibly, has led some benighted Americans to whisper once again of secession and civil war.”

The major news networks have been quick to focus on the book’s possible implications, and Larson has appeared on cable news, NPR, and at bookstores and lecture venues across the country to address the possible parallels between the people, places and events of the spring of 1861 and those of the upcoming presidential election.

Which begs two questions. First, is The Demon of Unrest a well-written, thoroughly researched history deserving of the intense scrutiny it is receiving? And second, does the history of the fall of Fort Sumter offer readers insights into the cultural and political divisions in which Americans now find themselves?

The answer to the first question is a resounding yes. Larson is a conscientious researcher, and everything he presents “comes from some form of historical document; likewise, any reference to a gesture, smile, or other physical action comes from an account by one who made it or witnessed it.” He has analyzed a myriad of primary and secondary sources and produced a narrative that proceeds logically from chapter to chapter, illustrating how a false sense of honor and faulty decision-making on both sides of the conflict facilitated the terrible suffering that would be occasioned by the war.

Larson accomplishes this by drawing on the papers and records of the usual suspects — Mary Chesnut, Maj. Robert Anderson (Fort Sumter’s commander), Lincoln, Edmund Ruffin, Abner Doubleday, James Buchanan, Gideon Welles, William Seward, etc. — but he also delves more deeply than earlier historians into more obscure sources, all of which are noted in his extensive bibliography. Much of what he discloses will be revelatory to readers of popular Civil War histories.

The disreputable activities of South Carolina Gov. James Hammond are a startling example. (Hammond is credited with having uttered the oft-repeated “You dare not make war on cotton — no power on earth dares make war upon it. Cotton is king.”) In May 1857, Hammond, an active player in the Fort Sumter narrative, was being considered to fill a vacant seat in the U.S. Senate, even though he was a confessed child predator who molested his four nieces. Hammond wrote in his diary: “Here were four lovely creatures, from the tender but precious girl of 13 to the mature but fresh and blooming woman nearly 19, each contending for my love . . . and permitting my hands to stray unchecked over every part of them and to rest without the slightest shrinking from it.” Hammond not only recorded his misdeeds, he disclosed his indiscretions to friends and suffered no negative political consequences when his pedophilia became public knowledge.

Larson reminds readers that Lincoln’s election also occasioned a demonstration at the Capitol. The crowd might have turned violent, but Gen. Winfield Scott was prepared: “Soldiers manned the entrances and demanded to see passes before letting anyone in. Scott had positioned caches of arms throughout the building. A regiment of troops in plainclothes circulated among the crowd to stop any trouble before it started.”

In a lengthy narrative aside detailing Lincoln’s trip from Springfield to Washington, Larson reveals that the president-elect had to hold a yard sale to pay for his journey to the inaugural and that despite precautions to ensure his safety, an elaborate subterfuge had to be undertaken to sneak Lincoln into the District of Columbia. He was accompanied on the trip by detective Allan Pinkerton, who was determined to foil a supposed plot to assassinate Lincoln before he could be sworn in.

What readers will find most surprising is the degree to which the 19th century concept of “honor” held sway over events surrounding the fall of Sumter. As South Carolina authorities constructed gun emplacements in preparation for a bombardment of the fort, mail service continued with messages to and from Washington passing through Confederate hands without being opened and read. While attempting to starve the fort into surrender, the city of Charleston also attempted to accommodate the garrison with deliveries of beef and vegetables, which Maj. Anderson rejected on the grounds that such resupply was dishonorable.

After months of political finagling, the fort endured an intense 34-hour bombardment before being evacuated. Neither side suffered any dead or wounded; thus, the battle that initiated the bloodiest conflict in American history was bloodless.

The second question — Do the events that followed Fort Sumter’s fall suggest that violent consequences will likewise follow the 2024 presidential election? — is easily answered: No. Cliches such as Santayana’s “Those who forget history are condemned to repeat it” or Twain’s “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme” short circuit critical thinking. Nothing is preordained.

Documentary filmmaker Ken Burns, who knows something about the Civil War, recently addressed this question in a commencement speech at Brandeis University. The text of Burns’ address is available online, and readers who believe we’re headed into a second civil war should read what Burns has to say.

The obvious message conveyed by The Demon of Unest is clear: Human beings are foolish, arrogant, and too often given to emotional irrationality that’s self-destructive. There’s nothing new under the sun. Ecclesiastes got that right. PS

Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of seven books of poetry and prose. He’s the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press Awards.