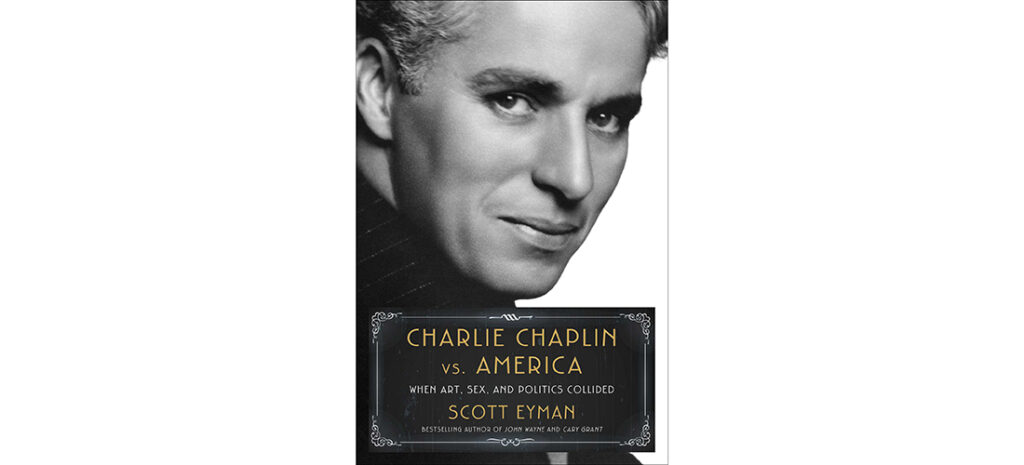

The Omnivorous Reader

Portrait of a Genius

When art and politics collide

By Stephen E. Smith

At a moment in our cultural/political history when we disagree about almost everything, you’d expect an ambitious pundit to pen a bestseller titled America vs. America: A Definitive Analysis of Our Cantankerousness. Although books aplenty attempt such revelations, it’s difficult, if not impossible, to articulate the forces at work in the here and now, but literary critic Scott Eyman has given us the next best thing to an explanation: Charlie Chaplin vs. America: When Art, Sex, and Politics Collided, an exposé/biography of a man who defined, at least in part, the last century, and who suffered the slings and arrows of an America gone wacky.

Eyman’s latest offering — he’s authored six previous books on the film industry and various movie stars — may strike readers as a story told a trifle too late. After all, Charlie Chaplin is ancient history, a wobbly, bowler-topped, black and white stick figure balanced on a rubbery cane who inexplicably entertained our grandparents with the silent knowledge that authentic comedy has its source in the concealment of anguish. The day-to-day details of Chaplin’s life notwithstanding, there’s insight aplenty in this cautionary tale of an artist whose universal popularity among Americans diminished to the point that he was run out of the country and forced to take up residence in Switzerland for the later years of his life.

Chaplin was born in England and suffered a childhood of poverty and hardship. His alcoholic father abandoned the family, and he and his brother were sent to a workhouse. His mother was committed to a mental institution when he was 14, and Chaplin was forced to find work touring theaters and music halls as a stage actor and comedian. At 19, he toured with a company that traveled the United States, where he eventually signed with Keystone Studios. By the age of 20, he was the best-known man in the world.

Chaplin co-founded United Artists and went on to write and produce The Kid, A Woman of Paris, The Gold Rush and The Circus. After the introduction of talkies, he released two silent films, City Lights and Modern Times, both film classics, followed by his first sound film, The Great Dictator, which satirized Adolf Hitler. After abandoning his Tramp persona, his later films included Monsieur Verdoux, Limelight and A King in New York. His credits and awards would fill this page, but less-than-knowledgeable readers need only grasp this basic fact: Chaplin was a creative genius who had a profound influence on popular culture and the art of filmmaking.

The focus of Eyman’s biography is Chaplin’s fall from grace. Early in his career, Chaplin was accused in a paternity suit in which he was found guilty, although blood tests proved conclusively that he was not the father (at the time, the state of California didn’t recognize blood tests as evidence); but the scandal was enough to attract the attention of gossip columnists, Hedda Hopper foremost among them, who were always collecting dirt on celebrity targets that would sell newspapers.

More destructive to Chaplin’s reputation was the public curiosity regarding his politics. Although he lived much of his life in the United States — indeed, he made most of his fortune here — he never applied for citizenship, which generated a cloud of suspicion that never quite dissipated. Chaplin claimed to be an anarchist, “not in the bomb-throwing sense,” Eyman writes, “but in his dislike of rules and a preference for as much liberty as the law allowed, and maybe just a bit more.” In truth, he was little interested in politicians and politics, outside the restraints placed on the arts by contemporaries who were politically minded.

Having suffered through a childhood of poverty, he harbored a great concern for the underprivileged, which is evident in all his films. But when he released Modern Times, which thematically explored the unending struggle against authoritarianism, and The Great Dictator, which mocked Adolf Hitler, both films, humorous but essentially didactic in intent, further thrust Chaplin into the political arena. Prior to our involvement in World War II, he publicly advocated an alliance with the Soviet Union, and members of the press and the public were scandalized by his marriage when he was 54, to 18-year-old Oona O’Neill, the daughter of playwright Eugene O’Neill.

Because of his support of Russia, Chaplin was accused of being a communist sympathizer, and the FBI opened an investigation, all of which fed into the Red Scare and McCarthyism of the early 1950s. Chaplin fell into such disfavor with the public that he was denied re-entry to the U.S. after leaving for the London premiere of his film Limelight.

Eyman’s book is a “social, political and cultural history of the crucial period in the life of a seminal twentieth-century figure — the original independent filmmaker who gradually fell into moral combat with his adopted country precisely because of the beliefs that form the core of his personality and films.”

Certainly, the activities of the press — particularly the gossip columnists who fed on Chaplin’s foibles; and the FBI, which launched a long, out-of-control investigation of Chaplin’s life — will give the thoughtful reader pause. FBI files on Chaplin ran to over 1,900 pages, mostly hearsay procured from dubious sources, material that was fed to friendly reporters who used the misinformation to besmirch Chaplin’s character and promote themselves.

Are there definitive elements in Chaplin’s life that precisely parallel the political/cultural moment in which we find ourselves? Probably not. As usual, Mark Twain is credited with having said it best: “History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes,” and readers, regardless of their politics, are likely to find themselves singing along with whatever sad tune history is humming at the moment. PS

Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of seven books of poetry and prose. He is the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press Awards.