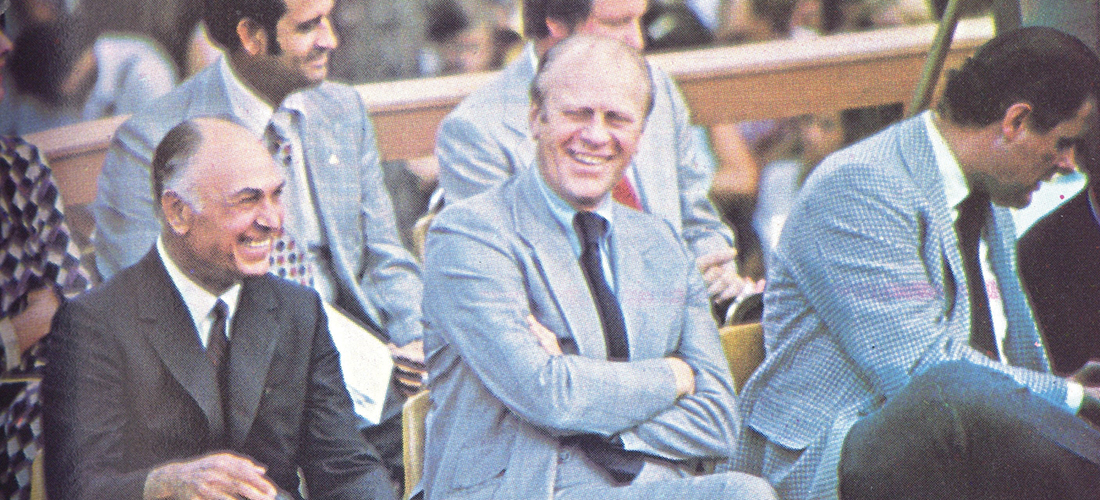

When President Gerald Ford joined eight of golf’s all-time greats

By Bill Case

On Sept. 8, 1974, just 30 days after being sworn in as president, Gerald Ford stunned the nation by granting his disgraced predecessor, Richard Nixon, a full and complete pardon for all offenses, known and unknown, committed by Nixon against the United States. Facing certain impeachment and Senate conviction as a result of his conduct during the Watergate scandal, Nixon had resigned on Aug. 9, resulting in the elevation of Ford to the presidency.

Some cynical observers hinted at a corrupt bargain — perhaps Nixon’s resignation was predicated on Ford’s pardoning him. Prior to granting the pardon, Ford had been showered with praise for restoring public confidence in the wake of the Watergate debacle. Post pardon, his brief honeymoon was kaput as a cascade of angry diatribes batted the president about like a piñata.

Earlier, when Ford was still vice president, representatives of Pinehurst’s new World Golf Hall of Fame had invited him to attend the opening ceremony honoring the first class of inductees, and he had agreed. On July 17, 1974, an above-the-fold headline in The Pilot reported that Ford was coming to the Sept. 11 ceremony. However, the vice president’s acceptance contained a caveat that, in retrospect, foreshadowed the political shockwave ahead. “From time to time emergencies do arise which are beyond my control and which might prevent my carrying out this obligation,” he wrote.

Soon after being sworn in as the 38th president, Ford did cancel his appearance. Don Collett, a Houston businessman who had been hired to lead the new Hall of Fame, acknowledged being “crushed” by this development. Sometime later, he received a call from a White House aide who indicated the president was reconsidering. Getting out of Washington, D.C., for a non-partisan event in the Sandhills might provide a brief respite from the controversy swirling around him. Before recommitting, however, Ford wanted to know who was going to be in Pinehurst and what would be expected of him. Collett provided details, and then tossed in a lure he considered irresistible. If the president came he could play a few holes with all the living Hall of Famers.

The World Golf Hall of Fame event was right up the president’s alley. An avid golfer, the powerfully built former center for the 1932-34 University of Michigan Wolverine football team was a long driver, though his game tended to be erratic. At the time, Ford claimed an 18 handicap, proficient enough not to embarrass himself in periodic pro-am appearances. More importantly, the president revered the game’s legendary players, and eight of the greatest still living — Ben Hogan, Sam Snead, Byron Nelson, Gene Sarazen, Patty Berg, Jack Nicklaus, Gary Player and Arnold Palmer — were coming to Pinehurst for their inductions.

Ford was especially looking forward to hobnobbing with Hogan, one of his all-time heroes. By ’74, sightings of Hogan outside his hometown of Fort Worth, Texas, were rare. The nine-time major champion had even stopped attending the annual Champions Dinner at the Masters — a tradition he originated. This vanishment from the stage only served to enhance his unique mystique.

Anxious days passed without further word from the White House. Then the aide phoned Collett again. This time he inquired, “Is Ben Hogan really going to be there?” When Collett replied affirmatively, the aide said, “That’s great . . . The president will be there.”

While it was a remarkable coup to attract a sitting president, Hogan, and the other golf legends to Pinehurst for its opening ceremony, the founding of the World Golf Hall of Fame itself was a notable accomplishment. The concept was one of several elements of a plan hatched by the Diamondhead Corporation, the Pinehurst resort’s owner during the 1970s. For a price of $9.5 million, the company had acquired the resort and accompanying 6,700 acres of undeveloped, mostly forested real estate from its founding family, the Tuftses.

The driving force behind Diamondhead was its creative founder and controller of 90 percent of the company’s stock, Malcom McLean. The North Carolina native made a fortune when he imagined a new and cost-effective way to transport freight across land in shipping containers on trucks that could then be transferred to ocean-going ships. After selling his trucking concern to R.J. Reynolds Inc., McLean founded Diamondhead, whose divisions included medical products, condominiums and resort properties.

Diamondhead’s top brass licked their respective chops at the potential windfall to be gained by subdividing Pinehurst’s forested real estate. Raymond A. North, writing for The Pilot, observed that “the land and condominium salesmen cluster with the intensity of ants on a piece of pie.” It took a lawsuit to derail company plans to erect housing alongside Course No. 2.

While many of the village’s old guard, including Richard Tufts, bemoaned Diamondhead’s approach, it was hard to fault the company’s avowed goal of making Pinehurst (without apologies to Scotland’s St. Andrews) the “Golf Capital of the World.” McLean entrusted the task of making that happen to Bill Maurer, Diamondhead’s president. Maurer, a former golf professional, believed dramatic measures were needed to ramp up the resort’s identification with the game, and his boss was willing to fund them.

For the branding to succeed, Maurer deemed it imperative to bring professional golf tournaments back to the resort. None had been held in Pinehurst since 1951, when Richard Tufts became disenchanted with the U.S. team’s behavior in that year’s Ryder Cup matches. Maurer was not content with hosting a garden variety PGA Tour event. As he phrased it, “If (Pinehurst) is the golf capital of the world, let’s really make it that. Let’s have . . . the World Championship.” Seeking prize money commensurate with the auspicious title, he persuaded McLean to bankroll the largest purse in golf history — $500,000.

To underscore its hoped-for importance, the 1973 World Open was set for a grueling 144 holes, double the usual 72. Intrigued by the prospect of capping off the PGA Tour’s season by crowning the “world champion,” Maurer secured dates for the event from Nov. 5 through 17. To his dismay, the World Open’s marathon length and late dates proved unattractive to several of the game’s elite, including Nicklaus, Lee Trevino, Johnny Miller and Tom Weiskopf, all of whom declined to enter. Marred by these negatives — and freezing weather — the tournament fell far short of a true “World Championship” in the minds of golf fans, the media and tour players.

The following year, the second World Open was shortened to 72 holes, the purse reduced to $300,000, and the date moved to the second week of September, perfect timing for Maurer to showcase another piece of his branding effort: the World Golf Hall of Fame. In March 1973, Diamondhead had broken ground on a white columned building with a fountain and reflecting pools, costing $2.5 million, to house the hall and museum behind the fourth green of course No. 2. It would be ready for the ribbon-cutting on the day prior to the start of the 1974 World Open, Sept. 11. The contemporaneous scheduling would focus public and media attention on Pinehurst as the unrivaled world golf capital.

Maurer had first considered the concept of bringing a golf hall of fame to Pinehurst in 1971. Since neither of the existing halls of fame, operated by the PGA of America and the LPGA, included international stars, an edifice that included foreign players would be a perfect fit for Pinehurst’s new “world” image. Collett, at the behest of Maurer, conducted a feasibility study and subsequently urged Diamondhead to press ahead. Maurer, in turn, obtained McLean’s buy-in. They hired Collett to be both president of the newly christened World Golf Hall of Fame and assume a similar position at Pinehurst, Inc.

Among the dizzying array of Collett’s responsibilities was acquiring artifacts for the hall. In October 1973, he successfully negotiated the purchase of an unequaled collection of ancient golf clubs from St. Andrews professional Laurie Auchterlonie. Collett also rounded up President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s golf cart and other memorabilia previously belonging to the Duke of Windsor, Walter Travis, Belgium’s King Leopold and the great Bobby Jones.

Diamondhead hired Pinehurst resident John Derr to be the World Golf Hall of Fame’s executive vice-president. Derr, a noted radio/television personality, writer, and raconteur, would help publicize the hall and serve as a liaison with the Golf Writers Association of America, whose members were to be involved with the nomination and election process.

Derr’s involvement, however, did not eliminate the contentiousness between Diamondhead and the GWAA in the period leading up to Sept. 11. Writing in the November 1974 edition of Golf magazine, columnist John Ross summed it up this way: “The alliance between Diamondhead and the writers has been a stormy one, the problem largely being the unwillingness of the Pinehurst operators to give control of the voting structure and procedures to the writers. The two-year hassle was still unresolved right up to moment of the induction rites.”

In fact, many higher-ups in golf, including those at the USGA, deemed it a non-starter for a private, profitmaking corporation to own and control the sport’s Hall of Fame and museum. Notwithstanding these criticisms, there was growing, if grudging, respect for Diamondhead’s expenditures of time and resources to make the hall a reality. Hogan himself would praise the founders: “I think it is wonderful and I think it is high time that golf had a ‘world’ golf hall of fame,” he said in an interview upon arrival in Pinehurst. “There have been small ones around the country and I think it’s great that Mr. McLean and Diamondhead Corporation have done this.”

Hogan’s dislike of travel had caused Diamondhead execs to fear he might take a pass on attending his induction. It was common knowledge that he had little interest in being feted and, according to Curt Sampson in his biography Hogan, “hated his reduction to ‘ceremonial’ status in the golf world, which gave other graying golf legends a reason to hit the road.”

On the plus side of the ledger was Hogan’s abiding fondness for Pinehurst. Course No. 2 was the site of his first PGA Tour victory following a decade of struggles — the 1940 North and South Open. He would win that tournament three times. Hogan also played magnificently in the 1951 Ryder Cup matches on No. 2. Furthermore, a return to Pinehurst would permit him to reconnect with Derr, the legendary champion’s American confidant during the 1953 Open Championship at Carnoustie, his last major victory.

Maurer, Collett and Derr breathed a collective sigh of relief when Hogan RSVP’ed “yes” after McLean offered to send his personal jet to fly Ben from Fort Worth to Pinehurst. Byron Nelson, Hogan’s lifetime rival after growing up together in the same caddie pen at Glen Garden Country Club, also hitched a ride.

But nailing down the president’s appearance was the biggest get of all. The maneuvering actually began in May of ’74 when Derr sought to invite Ford — still vice president — while both men were in Charlotte competing in the pro-am preceding the Kemper Open. Derr cajoled evangelist Billy Graham into greasing the skids for an introduction. The vice president expressed interest, but cautioned that before committing, an array of details needed to be worked out. After he succeeded Nixon as president and finally agreed to attend the opening ceremony, those details ballooned tenfold when frenzied preparation for the visit began.

The Secret Service descended on Pinehurst in early September, checking rooftops, motor routes and potential security issues. Longtime Pinehurst resident Peter deYoung, Pinehurst Country Club’s tournament coordinator at the time (and still active locally in organizing junior golf tournaments) made preparations for the president’s golf game on course No. 2. DeYoung recalls being advised by a Secret Service agent that aside from the first tee and the 18th green, no spectators could be permitted on the course. “With our limited resources, that’s impossible to arrange,” deYoung said.

The agent emphatically replied, “No, it’s not. And that’s what we are going to make happen.”

During the week, deYoung and the Secret Service agent established a congenial relationship, or at least deYoung thought so until just prior to the president’s arrival on Sept. 11. The suddenly hostile operative confronted him and demanded to know, “What’s that in your pocket?”

“A pack of cigarettes. I’ll take them out,” deYoung said, taken aback by the change in the agent’s demeanor.

“Don’t touch them!” warned the agent. “I’ll take them out myself.” A threat on the president’s life had been reported, and the agent was taking nothing, and no one, for granted.

The last nail wasn’t pounded into the new hall until the morning of the induction ceremony. The transfer of artifacts from a temporary location on West Village Green Road to the new museum continued right up to the 3 p.m. dedication.

Meanwhile, the honorees began arriving. Collett dispatched his young assistant at Pinehurst County Club, Drew Gross, to pick up Hogan at the airport. Gross, now resident manager at the Pine Crest Inn, was accustomed to meeting and greeting top pros, but shaking the hand of the legendary icon was nonetheless an electrifying moment. “When he looked me in the eye and said, ‘I’m Ben Hogan,’ all I could think to myself was, ‘No shit!’”

The festivities involved plenty of hoopla. Starting at 1 p.m., the living inductees and representatives of deceased honorees Harry Vardon, Babe Zaharias, Walter Hagen, Bobby Jones and Francis Ouimet would gather at the fifth hole of course No. 2. The 82nd Airborne Band would play, and the U.S. Army’s Golden Knights would stage a parachuting exhibition. On the descent from 4,000 feet, the paratroopers would display each golf legend’s national flag. After the Golden Knights touched ground, they would present the banners to the various honorees. Then, 200 yards away on the west steps of the new building, the dedication and inductions were to commence around 2:30 p.m. The Diamondhead men held their breath, praying President Ford would arrive in a timely manner. It was a blisteringly hot day, and prolonging the ceremonies would not be to anyone’s liking.

November opens our eyes to invisible worlds.

November opens our eyes to invisible worlds. The first frost is nigh. Daylight saving time ends on

The first frost is nigh. Daylight saving time ends on

Don’t forget to add a sweet treat to your lineup. Fall inspired turnovers are a handy and welcome tailgating snack. These stuffed puff pastry pockets can be made ahead of time and stored in the freezer, to be baked the day of your big event. Fragrant pears paired with silky-smooth butterscotch sauce and chopped walnuts make for a spectacular filling and, best of all, these baked goods are kid-approved, for all the youngsters in attendance.

Don’t forget to add a sweet treat to your lineup. Fall inspired turnovers are a handy and welcome tailgating snack. These stuffed puff pastry pockets can be made ahead of time and stored in the freezer, to be baked the day of your big event. Fragrant pears paired with silky-smooth butterscotch sauce and chopped walnuts make for a spectacular filling and, best of all, these baked goods are kid-approved, for all the youngsters in attendance.