In the early years of the 20th century, when hillmen were twirling the white spheroid at swat artists, baseball’s spring training was not the domain of Florida and Arizona as it is today. To sweat out the boilermakers and beef stew consumed over the winter, major leaguers moved all around the United States’ warmer climes. They came to places they could reach by train that had adequate and affordable lodging, a ball field a cut above a pasture, and town elders eager for publicity via all-caps datelines in big-city papers.

Teams ventured to a score of locations during this time, including Baton Rouge, New Orleans and Shreveport, Louisiana; Dallas, Galveston and Marlin Springs, Texas; Charlottesville, Norfolk and Richmond, Virginia; Augusta, Macon, Savannah and Thomasville, Georgia; Charleston, Columbia and Spartanburg, South Carolina; Memphis, Tennessee; French Lick, Indiana; Birmingham and Mobile, Alabama; Hot Springs and Little Rock, Arkansas; Los Angeles and San Francisco, California. (Babe Ruth hit his first professional home run on March 7, 1914, at Fayetteville’s Cape Fear Fairgrounds during an intrasquad game as a member of the then-minor league Baltimore Orioles.)

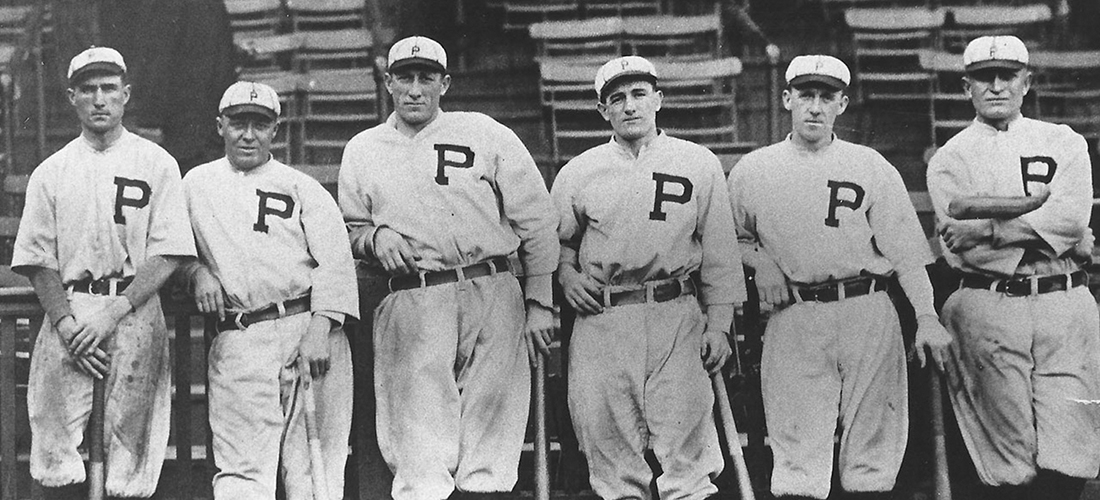

For three seasons, the Philadelphia Phillies got down to playing weight, knocked off the rust and otherwise readied for their National League schedule in Southern Pines.

The Phillies held spring training in Southern Pines in 1909, 1910 and 1913. In 1914, when Philadelphia, seduced by a fancy field in Wilmington, moved on, the Baltimore Terrapins came to town in 1914 to prepare for their first season in the short-lived Federal League. Familiarity hadn’t bred contempt for Terrapins player-manager Otto Knabe, who was a second baseman for the Phillies in their three Sandhills springs.

The Phillies had set up camp in Savannah from 1906 to 1908, but in early January 1909 Southern Pines officials wrote to club president Bill Shettsline asking him to visit and consider the town for spring training. “At a meeting of the councilmen and the golf club of Southern Pines last week the plans for taking care of the ball players, should they go there, caused considerable enthusiasm,” the Harrisburg Daily Independent wrote of the bid. “It was decided to improve the baseball grounds and to put in shower baths and a plunge.” Another paper reported that “every accommodation and facility for training were guaranteed.”

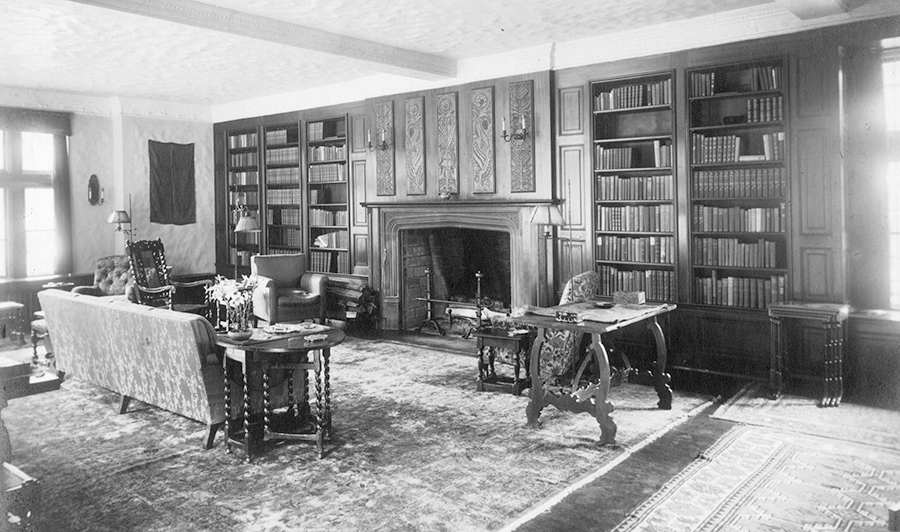

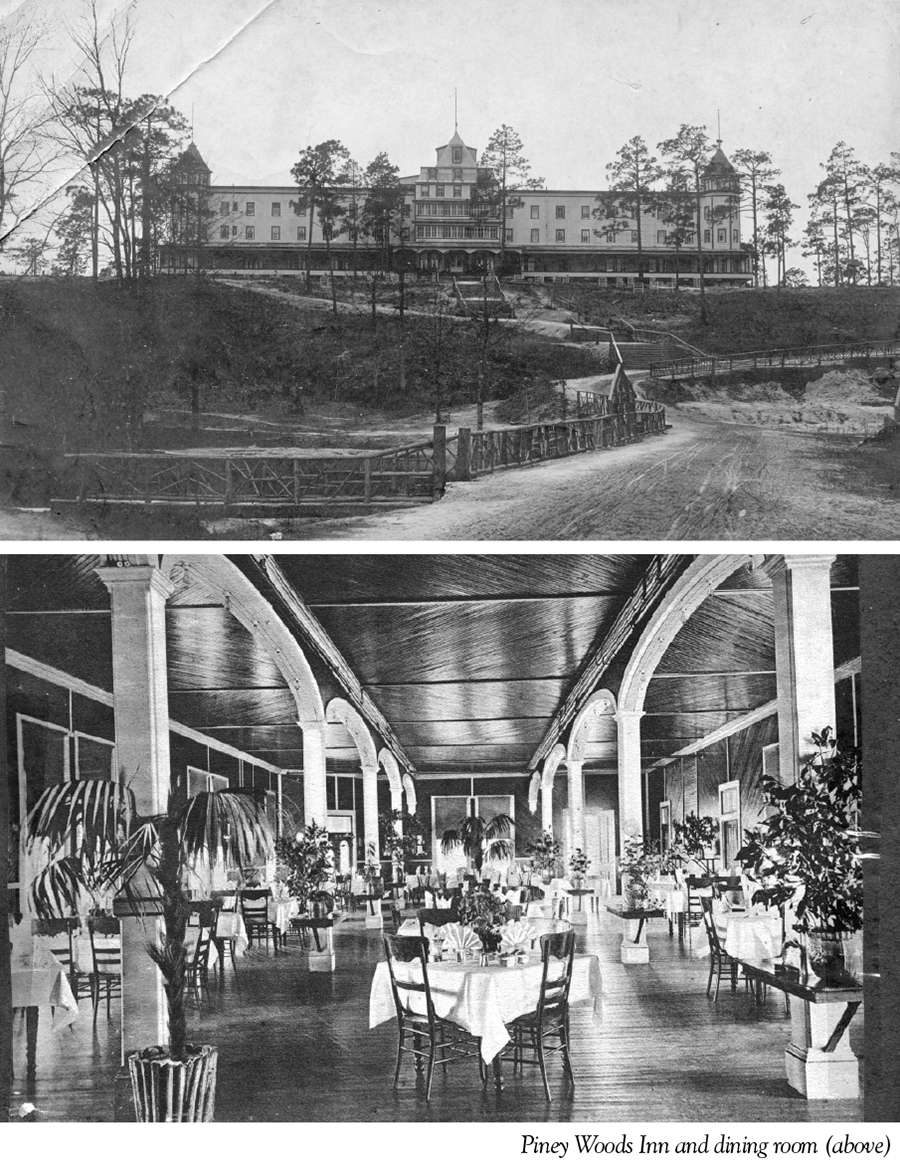

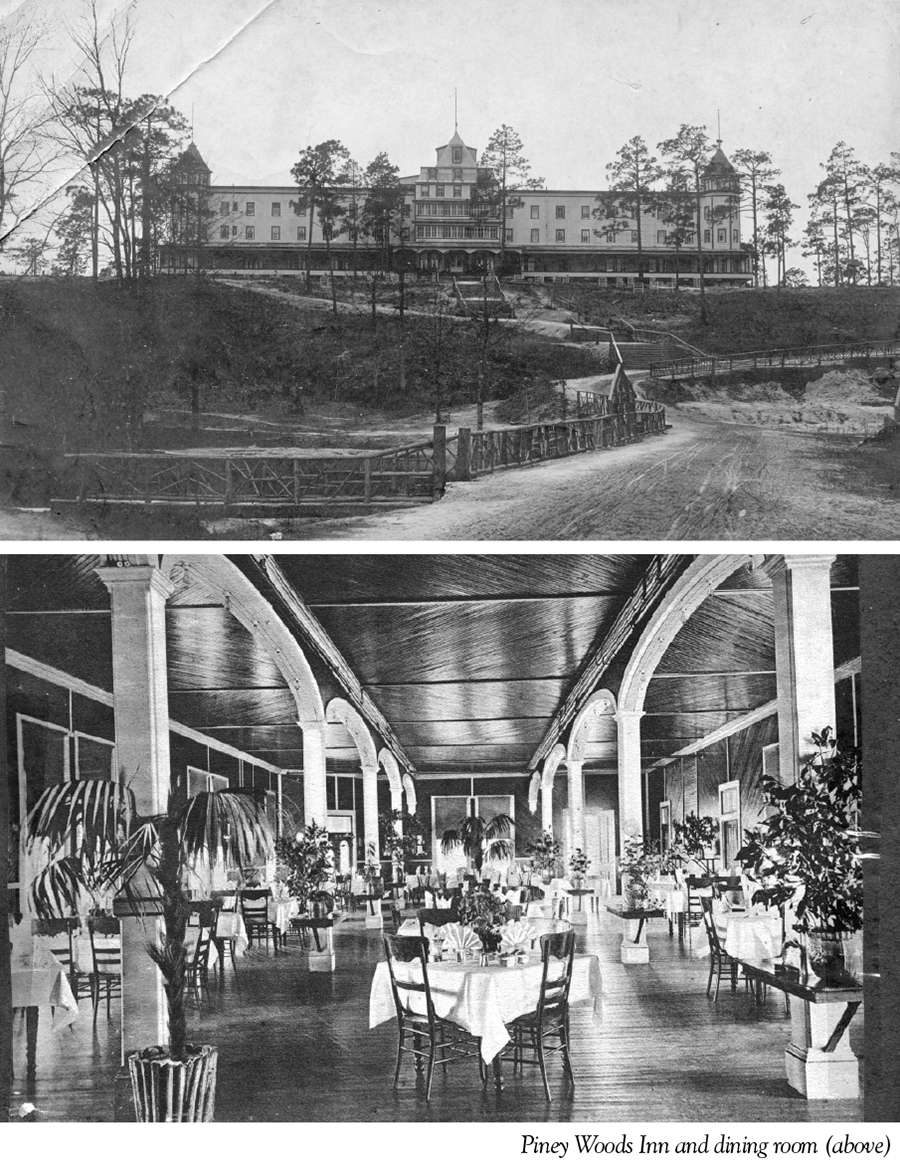

When Phillies manager Billy Murray left January 10, 1909, on a scouting trip of Southern camp possibilities, Southern Pines was his first stop. Murray liked what he saw — from the enthusiasm of the populace to the accommodations at the Piney Woods Inn to the quality of the baseball field next to Southern Pines Country Club, which had been established in 1906.

“The hotels here will be prepared to take care of the crowds, and they are assured of the best of treatment and of the generous hospitality of the townspeople,” The Tourist of Southern Pines boasted. “Mr. C.L. Hayward of the baseball committee has had a force of men at work on the grandstand, and it has been entirely renovated. Three extra tiers of seats have been added, the flooring renewed, and the whole stand braced inside and out. A canopy of canvas will protect the spectators in the grandstand from the direct rays of the sun.”

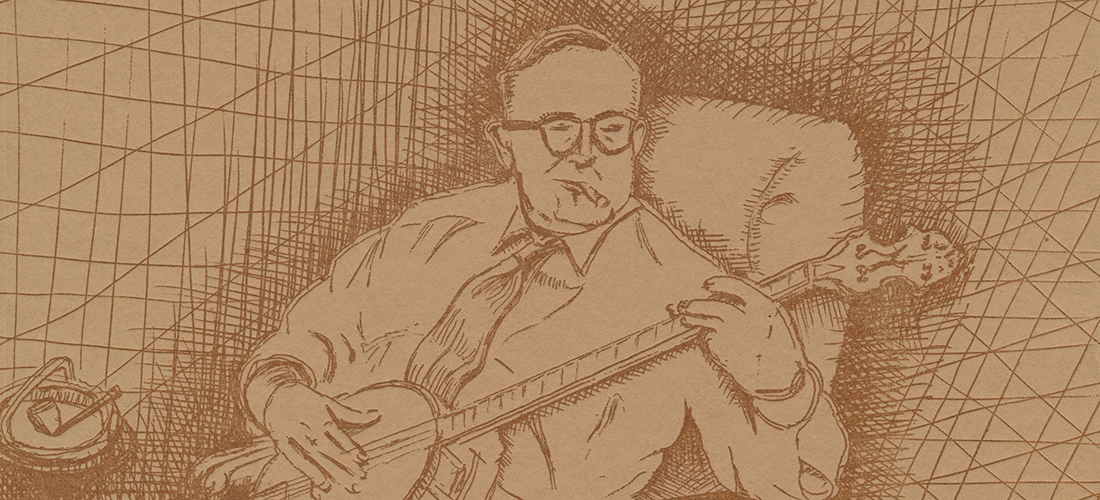

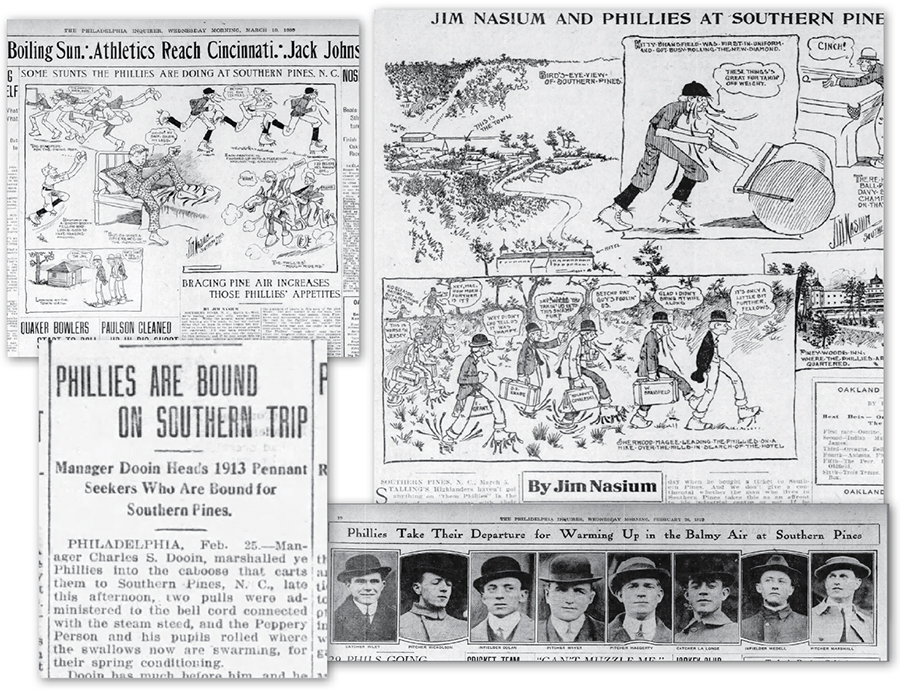

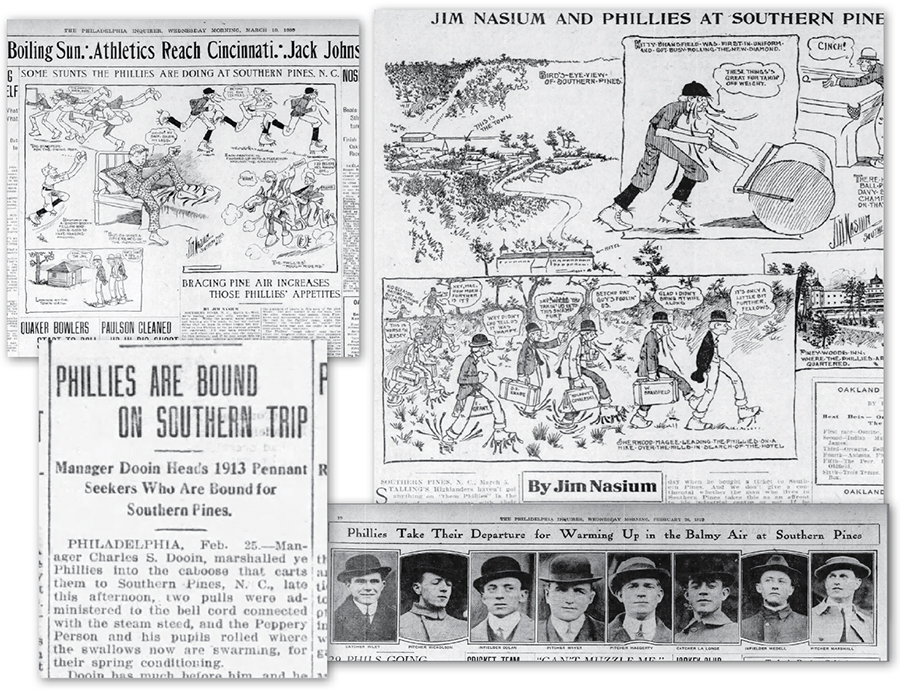

The Phillies arrived in early March after a 14-hour train trip. Among the traveling party was sports cartoonist and columnist Edgar Wolfe of The Philadelphia Inquirer. Wolfe, who used the pen name “Jim Nasium” and would become nationally known through his drawings in The Sporting News, chronicled each of the Philly team’s sojourns to Southern Pines.

Nasium endorsed the ball field, calling it the finest spring-training surface the Phillies had encountered in a long time, with black loam over sand rolled hard and smooth. “This means much in training the judgment and speed of infielders in early spring practice,” Nasium wrote, “besides greatly reducing the frequency of those delightful moments when an infielder gets plugged in the eye with a hot one that hasn’t any consistency in its action.”

The correspondent was less enthusiastic with the sleepy atmosphere in Southern Pines, population approximately 500. “When it comes to wide-awake towns,” Nasium said, “this little old village makes the average group of Southern plantation buildings look like a bustling metropolis in comparison.”

And Nasium rued the difficulty in finding a drink in the area. “Nut-brown is the prevailing style of complexions in this neck of the woods,” he wrote. “But you couldn’t get a nut-brown taste in your mouth here if you were President of the United States with a rattlesnake bite as big as an ostrich egg concealed on your person. This is one of those sections of the Sunny South where you can’t ‘look upon the wine when it is red,’ or any other color, unless you happen to personally be acquainted with some native who keeps a fire extinguisher in the house charged with ‘joy water’ for home consumption and the entertainment of guests.”

A lack of diversions wasn’t necessarily a bad thing for teams attempting to get their charges in shape. During the latter part of the 1800s, when pre-season getaways began (Boss Tweed’s New York Mutuals, an amateur nine, traveled to New Orleans in 1869, with the Cincinnati Reds and Chicago White Stockings warming up in the Crescent City the following season) and into the 20th century, the focus was on perspiration not strategy.

“ . . . For early camps were more fat farms than baseball camps,” Charles Fountain wrote in Under the March Sun: The Story of Spring Training. “The players of the day were given greatly to off-season dissipation . . . ” In Baseball: The Early Years, Harold Seymour noted that players frequently showed up in the spring “looking like aldermen.”

The Phillies were given every advantage to work off any off-season excesses in Southern Pines. There were many paths through the longleafs for walks to augment baseball drills. The 8-mile round trip to Aberdeen was a frequent training route. Being based near the country club, a majority of the players caught the golf bug and played every chance they got. Sherry Magee, the Phillies stalwart left fielder who in 1910 hit .331 to snap Honus Wagner’s four-year run as National League batting champion, often led the hikes and golf outings.

After a full day, the Phillies could sit on the veranda of the Piney Woods and, as Nasium wrote in the Inquirer, “bite off chunks of balsam-laden ozone that will assay 500 pounds to the bite and make you sweat turpentine every time the sun hits you.”

Because the food coming out of the Piney Woods kitchen was so tasty, the players had to mind their portions in order to keep their hard effort from being for naught. Certainly there were no reports of dissatisfied players such as Philadelphia Athletics catcher Ossee Schreck, who according to Fountain in Under the March Sun, “grew increasingly frustrated with the poor quality of the steak he was served at the team’s hotel and with the hotel’s seeming indifference to his complaints. Somewhere along the way, he secured a hammer and nail, and when another steak displeased him, he rose from his table and nailed the steak to the dining room wall.”

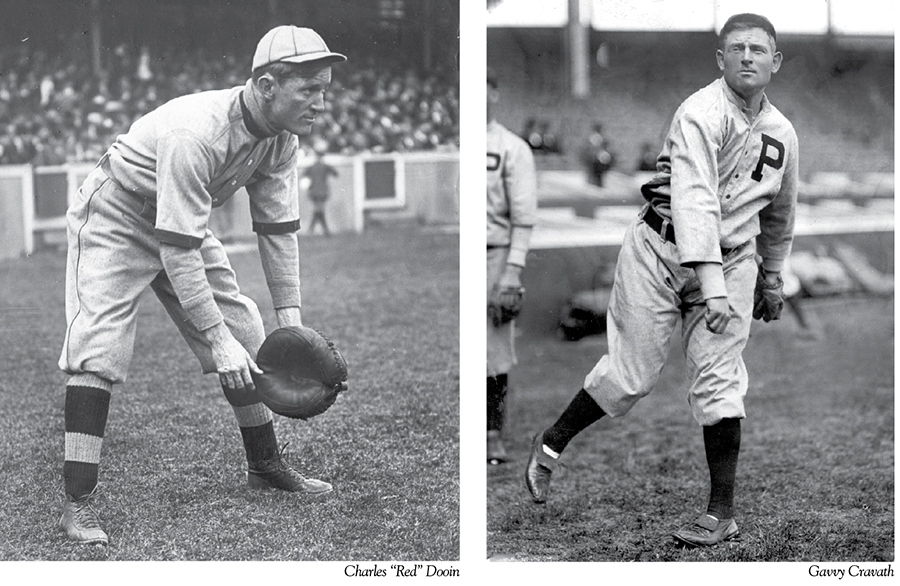

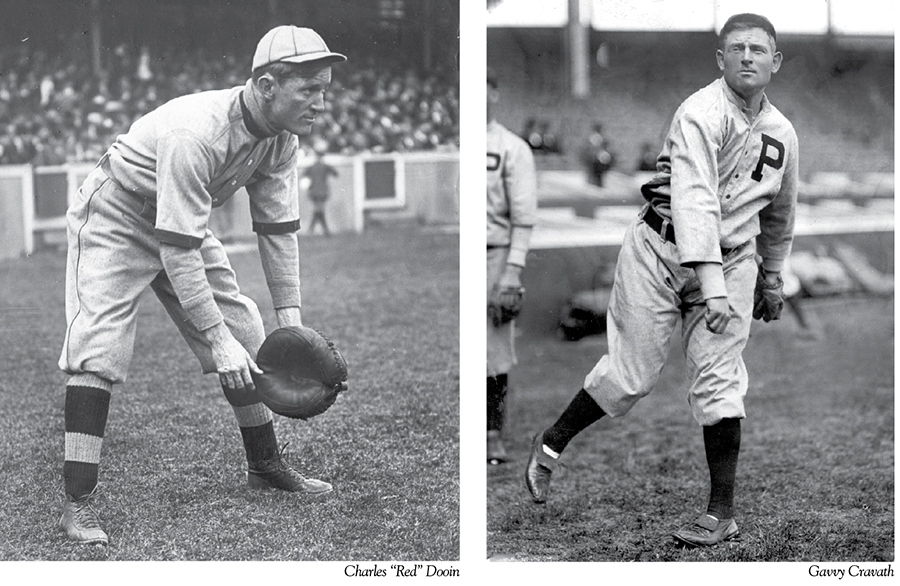

There was discontent about the wind and rain that sometimes marred March in Moore County, the latter a particular concern in 1910. New Philadelphia player-manager Red Dooin — a compact but feisty catcher sometimes called the “singing maskman” because of his off-season vaudeville work — was appalled at the condition of the field when he got to Southern Pines.

“Manager Dooin scared the golf club committee into seven different kinds of fits last night,” Nasium wrote on March 2, “when he threatened to pack up his trunks and take his bunch of ball tossers to some other spot on the Southern map where there was an inch of smooth ground to practice on.”

It turned out to be an idle threat. Dooin calmed down as town officials scurried to make improvements to the diamond. But four players wished the team had decamped.

As the Phillies slept in the Piney Woods Inn on Sunday, March 6, a severe storm rolled in with heavy rain starting at 2:30 a.m. Forty-five minutes later a powerful lightning bolt hit the cupola of the wooden structure. “Suddenly the heavens were lit up with a flash of fire which shot down on the hotel,” the Inquirer reported. “It tore away the big flag-pole on the corner of the roof, burned a big hole through the shingles and went through two floors, splintering the woodwork, shattering many window panes and scattering plaster all over the corridor.”

The worst damage occurred in a room housing Johnny Bates, Lou Schettler, Jim Maroney and Harry Welchonce, where the lightning ripped a hole in the ceiling above Maroney’s bed, sending a chandelier and plaster debris crashing down on them.

“That the big pitcher was not killed,” the Associated Press wrote of Maroney, “was due to the fact that a gaspipe, extending across, acted as a conductor and shunted the lightning away.”

The four players were stunned and shaken — Schettler unable to speak for two hours — but miraculously weren’t injured. For Welchonce, the incident brought back bad memories of a close call from lightning a few years prior and was part of an odyssey of misfortune that limited the highly touted minor leaguer to only play a total of 26 games in the majors. In addition to the lightning-strike scares, Welchonce battled shoulder injuries, was hit in the head by a pitch and contracted tuberculosis.

Surprisingly, despite the litany of problems, he had a long life, dying at 93 in 1977.

Led by Magee’s hitting and the pitching of Earl Moore, who led the league in strikeouts, the Phillies improved slightly on their 74-79 record of 1909, going 80-73 and finishing fourth in the National League in 1910. By that fall, though, they had decided to go elsewhere for spring training. Philadelphia traveled to Birmingham in 1911 and Hot Springs in 1912.

The Arkansas locale, where the Dodgers and Pirates also prepared for the 1912 season, made a push to get the Phillies to return in 1913. But Southern Pines recruited them as well, and with promises of a good practice field and comfortable rooms at the Pine Cone Inn — the Piney Woods Inn had burned down since their last visit — Philadelphia headed to Moore County again.

“Instead of the snow which greeted their vision in 1910,” the Inquirer wrote upon the Phillies’ arrival in North Carolina, “old Mother Earth was just donning her gown of green, the sun was shining bright and getting warmer every minute. It was a glorious sight for a bunch of tired old ball players and it made every one sniff and show new life.”

Dooin, who had suffered a broken ankle in 1910 and a broken leg in 1911, the latter on a vicious collision as he tried to block home plate in a game against the St. Louis Cardinals, would be more manager than player in 1913, taking the field in only 55 games. The skipper had players to fill the void, though.

Gavvy Cravath, who joined the Phillies in 1912, had a great year in 1913. Cravath led the National League in hits (179), home runs (19, no tiny number in the Dead-Ball Era) and RBIs (128, setting a National League mark that stood until Rogers Hornsby broke it in 1921). One of baseball’s greatest pitchers, Grover Cleveland “Pete” Alexander, also limbered up for the 1913 season in Southern Pines after opening a pool hall in his native Nebraska over the winter. Alexander went 22-8 in 1913 and won 373 games in his long career, tied for third all-time with Christy Mathewson and trailing Cy Young (511 wins) and Walter Johnson (417).

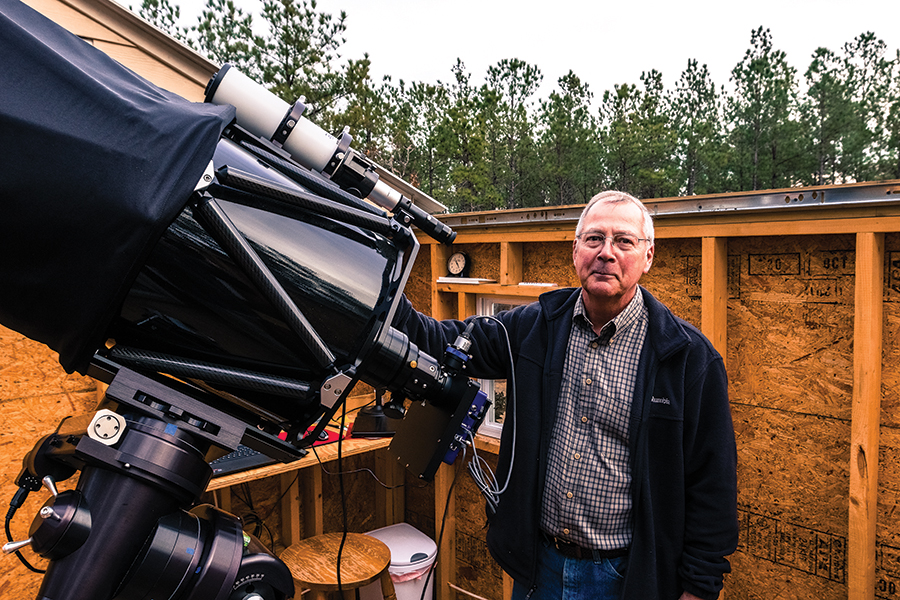

In their third trip to Southern Pines, the Phillies enjoyed better weather and field conditions than they experienced in 1910. As during their previous visits, they liked being able to play golf on the country club course as well as utilize it for conditioning runs. Yet by the time they departed town at the end of March 1913, it was clear that all was not perfect on the golf-baseball front.

Southern Pines Country Club had expanded to 18 holes and golf had grown in popularity with more visiting golfers. “The country club will not permit a high fence to be built around the outfield so as to protect the players from the strong winds,” a reporter noted, “and some of the golfers object to a ball field being so close to the links.” The club also indicated plans for tennis courts where the diamond was situated, likely meaning that a new field would have to be constructed somewhere else in town.

In writing about the Phillies’ spring training plans in December 1913, Nasium addressed the underlying tension. “The Phillies like to play golf — and the golfers didn’t want their sacred links invaded by a lot of professionals,” he wrote. “As the golf course started back of the ball club’s grandstand, it was very annoying to the golfers to have to dodge foul balls, or to have part of the links walked over every day by a lot of ball fans on their way to see the Phillies play.”

During 1913 spring training, the Phillies went to Wilmington on March 20 for a game against the Orioles. The Phillies won the game, 5-1, and Wilmington won over the Phillies, local officials turning out in force and hosting a barbecue after the game. In 1914 the Philly club headed to Wilmington to prepare for the season. But it was snowing upon their arrival, and it turned out to be one-and-done for Phillies’ spring training in the Port City. The teams would visit 13 different cities before settling in Clearwater, Florida, in 1947.

The Terrapins were a hit when they trained in Southern Pines in 1914 for the first Federal League season, staying in the Southern Pines Hotel and working out at the Phillies’ old spot by the country club. When the Terrapins left on the train in early April, The Baltimore Sun noted: “Pretty nearly the whole town turned out to say goodbye to the boys, and, as usual, every Terrapin felt just a little sorry he could not take the whole bunch along.”

Despite the support, in 1915 the Baltimore club conducted spring training in Fayetteville. No major league team returned to the Sandhills to tune up for a season.

The only spring training encore came more than three decades later when some of the Detroit Tigers’ minor league squads set up camp in Southern Pines in 1950-51. The Class C Butler (Pennsylvania) Tigers and Class D Jamestown (New York) Falcons trained in ’50, and in ’51 Jamestown was joined by two other Class D squads, the Richmond (Indiana) Tigers and Wausau (Wisconsin) Timberjacks.

“A good many fans have been out to watch the boys at work and report them a good-looking, clean-cut bunch,” The Pilot reported in 1950.

The farm clubs played at Memorial Field, their foul balls no threat to any golfers who by then were taking their shag bags to the grounds that long ago had been home to the Phillies, working on pitches of their own and most likely unaware of Southern Pines’ brief brush with the big leagues.