Exploring deep space in Jackson Springs

By Jim Moriarty

Celestial Photographs by Jeff Haidet • Earthbound Photographs by John Gessner

It’s not necessary to climb a mountain to reach the stars, but sometimes you have to dress like it. During the great January freeze of 2018, when the polar vortex decided to dispatch its nose-hair-freezing temperatures south, Jeff Haidet spent his evenings in the Grande Pines Observatory with the roof open, staring into deep space and a case of frostbite at the same time. Maybe not frostbite. His base camp, well, house is less than a hundred yards away. Nonetheless, here is a man who makes hay when then the sun doesn’t shine. Or the moon. “Everyone he knows, knows he hates the moon,” says Jeff’s wife, Vicki. If your intention is to draw a bead on the Running Man nebula in the constellation Orion, the glow of the moon is nothing more romantic than a bad case of light pollution.

The Grande Pines Observatory is as likely to be mistaken for the Gemini Telescope as Jackson Springs is for the top of Mauna Kea, but it’s surprising what can be seen if you know where to look. Most people have a shed for gardening tools. The Haidets have one for citizen science. The official observatory code of the 10-by-12-foot building is W46, the number associated with the data Haidet voluntarily supplies to the Minor Planet Center, part of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, and to the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona. One is the worldwide clearinghouse for all things asteroid, the other is Near Earth Objects.

One does not provide data to these institutions by picking up the phone, calling an 800 number and saying, “Dude, write this down.” They won’t talk to you until they know you’re worth listening to. “You have to send them data to prove you can get to the tolerances they want. You’re getting down to an accuracy of less than an arc second,” says Jeff. “An arc second is a dime at 2.4 miles. Put a dime somewhere down in Foxfire, and we can measure it from here with the right techniques and the right equipment. That’s the kind of accuracy you have to get.”

When the Minor Planet Center publishes its astrometric observations in its Circulars, Jeff may have 20 line items in it. The big boys might have 50 pages. “The pros do this a different way,” he says with a smile. The Lunar Planetary Lab is part of a mission that will likely reach its target, the asteroid 101955 Bennu, this August. “They’re going to sample material from the asteroid and bring it back,” says Jeff. “So they had a citizens science program to provide them with data on other possible targets after they’re done with Bennu. They put out a list: We need data on these six this month. They use it in their planning. It was science that I had the equipment and the methodology to do.”

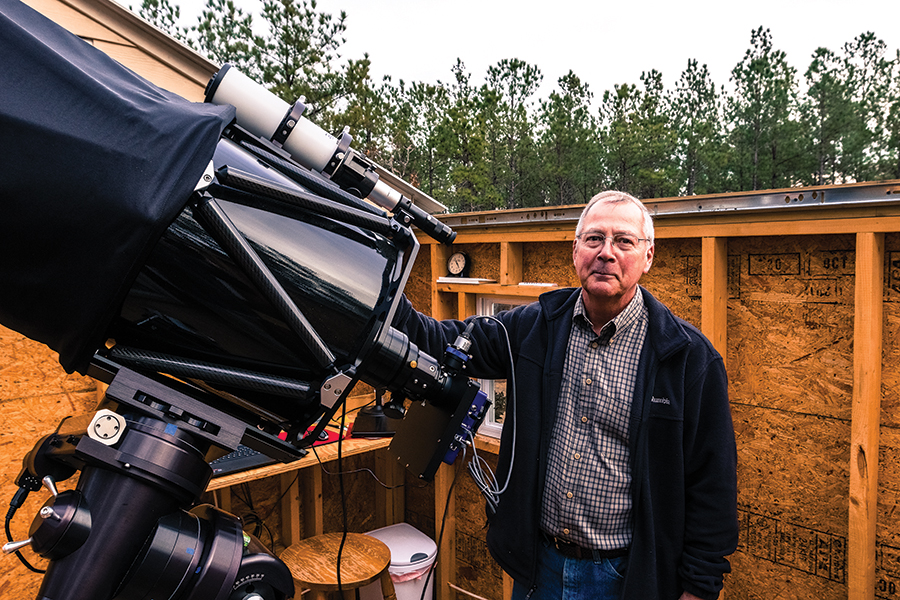

So, back to this unusual shed. For one thing, the sliding garage door is on the top. Then inside, instead of a riding lawnmower, there’s a Losmandy Gemini 2 mount held in place by 700 pounds of concrete pillar poured into the ground. You could jump up and down on the detached plywood floor and the telescope from Guan Sheng Optics, a Taiwanese company, won’t even know you’re in the same state. Jeff’s astronomical camera, acquired just before Christmas last year from QHYCCD, completes the outfit while the Lenovo laptop processes the data.

“I was doing visual observing, which you do until your eyes start to go a little bad,” says Jeff. “Mostly you’re looking at faint galaxies, nebula, so, if you want to stay in astronomy you do imaging. It’s almost all working together now. There’s a lot of moving pieces. When it works it’s kind of fun, but when it doesn’t work, it’s frustrating. It takes patience and time to learn how to do it. The other night I was taking pictures of this one nebula and I’m looking at some of the pictures when I got back in the house, and there’s an airplane going right through it. Throw that away.”

Naturally, no workplace is complete without a few personal touches, like the Grande Pines Observatory sign the Haidets’ son, Brian, an N.C. State University physics and engineering graduate who is working on a Ph.D. at UC-Santa Barbara, made to hang near the observatory’s doorway. Then there’s the tiny homemade heater Jeff rigged up to prevent dew forming on the optics on cool mornings. Addressing the tobacco barn effect of the summer heat is high on the to-do list. And, he’ll eventually replace the weights he has duct-taped to the telescope mount. “The scope and the equipment weighed more than I anticipated. I found some barbell weights and strapped them on there,” he says. Gravity doesn’t seem to resent improvisation. The paper bags suspended beneath the crown of the roof at either end are key pieces of environmental engineering. When the observatory was first built, pre-telescope installation, wasps seemed to be of the opinion the building had been erected as their personal clubhouse. Jeff solicited advice among astronomy bloggers and found the solution — scarecrows for wasps. “Take an empty brown bag, blow it up, tie it off and hang it up there,” he says. “Apparently wasps, the type that would nest in here, are very territorial. So they’ll come in and see it and think that’s a nest. It actually works. I have not had a wasp since.”

There have been a lot of different reasons to move to the Sandhills. Pinehurst’s founder, James Walker Tufts, thought people would come for the cleansing ozone of the pines. The Haidets, however, might be the only people who ever moved to Moore County for the dark. “We were looking for dark skies and warm weather and I’m a golfer,” says Vicki, who plays off a sporty seven handicap. Having horse farms nearby was particularly enticing. Open spaces. No street lights. No floodlights from the neighbors. Five and a half years ago they found the perfect lot in Grande Pines and with the removal of a modest number of trees, created the southern horizon Jeff needed to scan the sky.

Ohioans both, she grew up in Toledo and he in Alliance. Vicki learned to play golf at Inverness Golf Club, another of Donald Ross’ famous courses, and Jeff learned astronomy with the help of Dr. James Rodman, the astronomy professor at Mount Union College who was a friend of his parents — Lavern and LaVerne — and lived a few blocks down the street. “I don’t know how it would have gone without him, but he helped a lot,” says Jeff, who attended Case Western Reserve when it was still the duopoly of Case Institute of Technology and Western Reserve University. “We had the distinction at Case Western Reserve, when they merged, of having the nation’s two worst football teams,” says Jeff. “We got beat by Carnegie Mellon one year 72-6.” At least they scored — some solace for an institution that has an affiliation, one way or another, with 17 Nobel laureates.

“When I was about 5, I got a telescope for Christmas, and I forget now what it was — either Saturn or Jupiter — was in the sky that morning,” says Jeff. The oohs and aahs were followed by serious study. He built his own telescope; in fact, he has built several, grinding and polishing the mirrors himself. “When you’re a boy, you have no money but you have time, so you build things,” he says.

It wasn’t as though Jeff could go to YouTube and download a “How to Build a Newtonian Telescope” video onto his smartphone. Think library. Think books. Think Dr. Rodman. “Imagine these two round discs of glass. One is going to be your mirror and one’s called a blank,” he says. For hours at a time, day after day, you apply a heavy grit. “It’s all in the pattern you use,” he says. Eventually, one piece becomes concave, the other convex. When it reaches the curvature you want, you test the focal length. If that’s where you want it, you begin using finer grits for a smooth finish. After that comes the polishing with optical rouge, similar to what jewelers use. “The problem is, you don’t want it to be a perfectly spherical mirror,” says Jeff. “It needs to be parabolic.” Enter the pitch lap. And so on. “Grinding it wasn’t that bad,” says Jeff. “Polishing it would take a lot of time. The tolerances are very tight and it would take weeks to get it right unless you’re really lucky.”

Jeff graduated from Case (he stuck with the old diploma) with a degree in astronomy and physics. When he graduated in ’72, the National Science Foundation budget had mostly dried up, so he left astronomy behind, using his computer proficiency to land a job with Owens Corning. He got a Master’s degree in computer science and engineering from Ohio State and spent his career at Owens integrating the shop floor equipment with the enterprise systems until he retired in 2008. Vicki graduated from Bowling Green State University, met Jeff when they both worked at Owens Corning and, after Brian turned 4, struck out on her own as a marketing consultant until she retired three and a half years ago.

It wasn’t until the late ’90s that Jeff was able to get back into astronomy. But Sylvania, Ohio, hard by Toledo, wasn’t the place for it. Every night session was a road game. “You had to travel about 45 minutes to get to where you had a dark sky. It’s a pain to drag all your equipment out and get all set up and aligned and calibrated,” says Jeff. Wouldn’t a backyard observatory be so much simpler?

Thanks to his “store bought” telescope with the Ritchey-Chretien optical design that matches up well with the big sensors in the new camera, deep space is only a few yards away. Auto-guiding allows him to expose the camera for an hour and be spot on the entire time. “Primarily what I had been doing is precise measuring, but with this camera I can do really good deep sky photography,” he says. “The new cameras, you take a series of exposures through different filters and then you stack those together to make the color image. Those really fancy pictures you see, those aren’t by accident. Those take time. A lot of knowledge, how to get the colors right, get the gradient across the background right, get all the noise out of the picture. It’s a serious thing.”

And best done in the dark.

Jim Moriarty is senior editor of PineStraw and can be reached at jjmpinestraw@gmail.com.