The Reluctant Pilgrim

By Jim Dodson

Two decades ago, on the eve of the new millennium, the acclaimed Cambridge biologist Rupert Sheldrake was asked what single change in human behavior could make a better world.

Every tourist, he replied, should become a pilgrim.

Sheldrake earned the distinction of being the “world’s most controversial scientist” because he rejected the conventional belief that nature and the universe can only be explained by scientific data.

His journey from atheism to an ever-expanding spiritual awareness and eventual embrace of his Christian heritage produced several fine books on the subject along the way, but it began with his simple curiosity about the common spiritual practices of the world’s religious traditions, highlighted by pilgrimages that awakened and expanded his own evolving views of human consciousness.

What Sheldrake was getting at, I think, was that a tourist travels the world in search of new experiences that provide superficial pleasure or delight, a material quest, if you will, that looks outward rather than probing inward.

A pilgrim, on the other hand, travels over unknown territory with an open mind and spirit willing to face any physical obstacle that arises, stepping out of the daily routine to deepen one’s awareness of a divine presence and the journey within. Pilgrimages are as old and varied as the world’s many religions, personal journeys that mean different things to every pilgrim.

Two decades ago, I took my dying father on a journey back to England and Scotland to play the golf courses where he learned to play the game as a lonely airman just before D-Day. Ours wasn’t a conventional spiritual pilgrimage, I suppose, though in retrospect I see it as something akin. For 10 days we traveled and talked about his life and mine, leaving nothing unspoken between us, ushering his long journey to a beautiful close and enriching mine in ways I’m still counting up today.

A couple of years later, in the midst of an unexpected divorce, my young daughter, Maggie, and our elderly golden retriever spent an entire summer camping and fly-fishing our way to the fabled trout streams of the West. Like a couple of modern-day pilgrims from Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales — or maybe a Hope-and-Crosby road movie — we went in search of new meaning and old rivers, lost the dog briefly in Yellowstone, blew up the truck in Oklahoma, saw soul-stirring countryside and met a host of colorful characters who made us laugh and cry, creating a bond my daughter and I share to this day.

When Maggie’s little brother, Jack, asked to have his own mythic adventure, we took off the summer before 9/11 hoping to see every wonder of the Classical World. Owing to events in a suddenly unraveling planet, age-old conflicts in the Middle East, China and Africa, we only got as far as the island of Crete before turning for home. But traveling together through the ruins of a mythological world — following the footsteps of Homer and Herodotus, Marcus Aurelius and Aristotle — brought us both a deeper understanding of how we got here. Today, my son works as a documentary journalist in the Middle East, still trying to make sense of its age-old conflicts.

As it happens, I wrote books about these family adventures, which in my mind perfectly fit the definition of a spiritual pilgrimage, a journey over unknown ground that mystically leaves the traveler changed for the better.

Last August, my wife and I joined 30 other pilgrims from our Episcopal Church for a more traditional spiritual walk along the Via Francigena — the ancient pathway linking Canterbury to Rome. In Medieval times, Christian pilgrims traveled the long road to pay homage to the tombs of the apostles Peter and Paul before catching ships to the Holy Land.

I’ll confess, at first I was hesitant to go — a reluctant pilgrim who prefers to walk alone — or with only one or two others on such travels.

In a sense, my wife and I reversed this ancient tradition by making our first trip to the Holy Land weeks before our Tuscan walk to attend my son Jack’s wedding to a lovely Palestinian gal he met in graduate school at Columbia University. The wedding festivities lasted several nights in Old Jaffa, the ancient port town next to Tel Aviv, where legend holds that Saint Peter received his vision to take Christianity to the gentiles of the Levant.

For the father of the groom, perhaps the most moving moment of this life-changing journey came on the morning of the ceremony when my wife, daughter and her fiancé Nathanial went for a swim on the beautiful beach that links the modern city of Tel Aviv to the ancient one of Jaffa. Afterward, following Arab tradition, I walked to the Char family patriarch’s house to ask permission for his beautiful granddaughter to marry my son. Tannous, 77, smiled and gave his blessing and we shared an embrace as both familiess applauded and music broke out.

An hour or so later, the wedding took place at a stunning basilica on the bluffs over the Mediterranean Sea. The rooftop celebration went on well after midnight beneath a full summer moon, prompting my own bride and me to slip away and stand on Jaffa’s famous Bridge of Wishes, where we quietly renewed our own wedding vows — for it was our wedding anniversary, too. As we walked home to bed through Jaffa’s moonlit streets, I suddenly remembered that I’d left my watch on the beach where we swam that afternoon.

True, it was only an inexpensive Timex Expedition watch, one of half a dozen Expeditions I’ve owned — and lost — over the decades. But in this instance, it seemed like a metaphor for our travel through time and space.

The last full day of this family pilgrimage was spent following a scholar from Hebrew University through the familiar and rarely explored corners of Old Jerusalem, whose famous public spaces — the Wailing Wall, the Via Delorosa, the Church of the Sepulcher, the Dome of the Rock — were jammed with tourists throwing down money on “holy” relics and cheap souvenirs while young Israeli guards kept watch with Uzis in hand, a stunning contrast that made these famous pilgrimage sites feel oddly oppressive.

It was only in the much quieter Armenian and Christian sectors of the old city, where tourists rarely venture and the churches are spectacular, airy and cool, that I found myself breathing easier and wondering why the so-called holy sites had felt anything but.

An answer of sorts revealed itself weeks later when we set off on foot with our fellow pilgrims on the Via Francigena, an 80-mile walk through the stunning countryside and soulful hill towns of Tuscany.

On our first day out, we walked 18 miles through lush vineyards and olive orchards — sampling ripening grapes and recently cured olives as we went — traversing a forest where the annual wild boar hunt had just begun. Owing to my dodgy knees, I volunteered to be a sweeper bringing up the rear of the group, a pattern I repeated all week. This allowed me to walk at my own pace, get to know other pilgrims who took their turn bringing up the rear, and travel at my leisure, frequently by myself for hours at a time, entirely off the clock of the world and my lost Expedition watch — as our group leader Greg liked to say — off the hamster wheel of our lives.

At the end of each grueling hike, I enjoyed getting to know my fellow travelers over pasta and good red wine, rowdy fellowship and swapping tales of blistered feet and the day’s ah-ha! moments. The excellent gelato cured a lot of what ailed my aching feet and muscles.

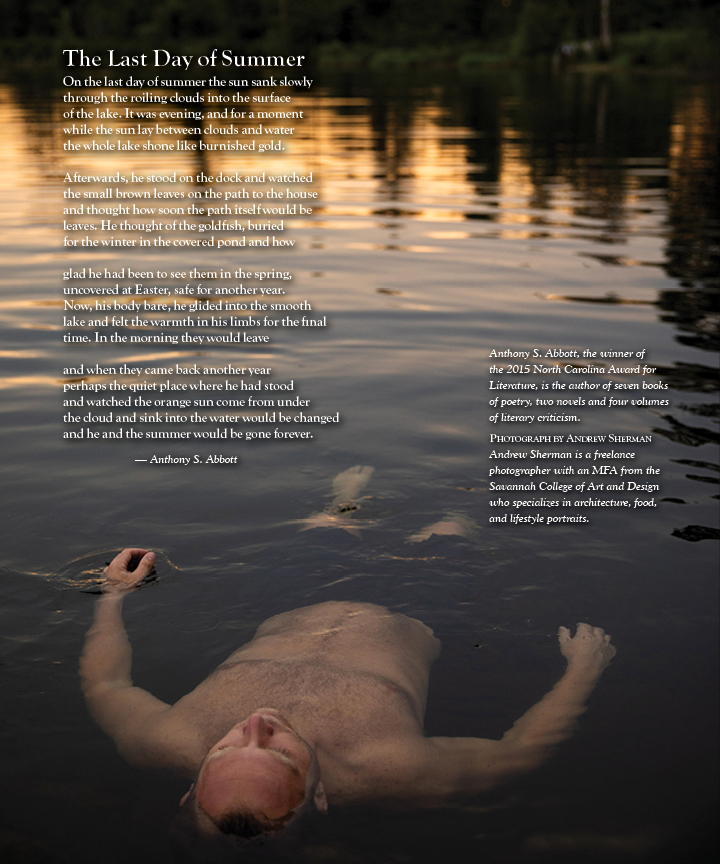

For this pilgrim, however, it was the quiet hours of walking alone or with my wife that I came to savor most, following a stony trail traveled by untold thousands before us across the ages, through deep forests or over sweeping hilltops where distant villages and Medieval abbeys — our destination each day — sat like painted kingdoms in a Medici fresco.

My only real concern was the fabled Tuscan heat of late summer. But after walking for two days in the heat, something rather marvelous happened.

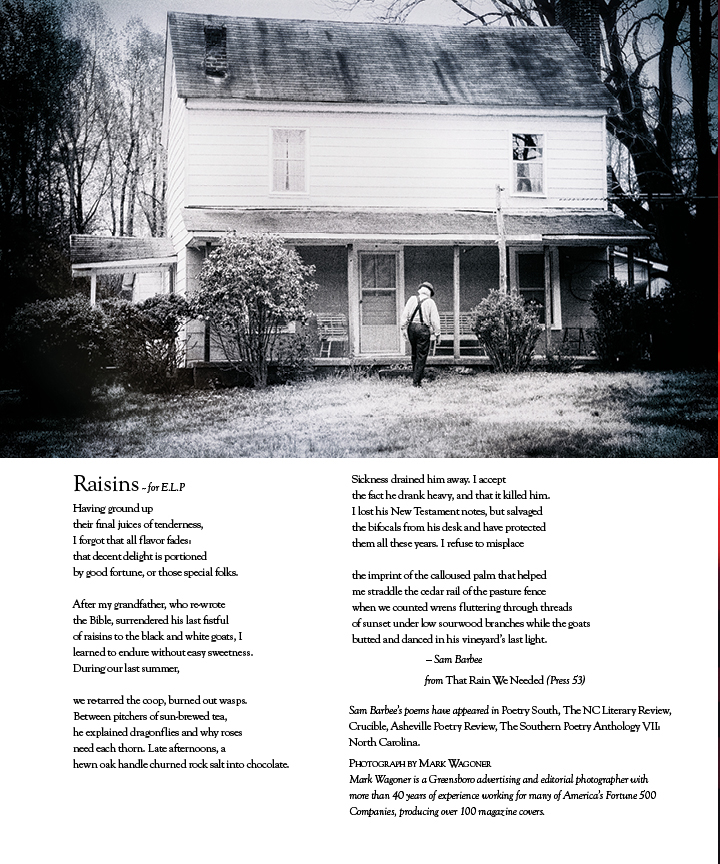

I emerged from a deep glen where I’d stopped to look at chestnut trees and wild mushrooms to find Wendy waiting for me on a rise in the stony road, just as a thunderstorm broke and a cooling rain fell. Over the hill, we came upon idle orchards and an abandoned farmhouse being reclaimed by the wild.

We sheltered there for a while, soaking in the glorious rain, looking at the vacant rooms, wondering about the people who once called this beautiful ruin a home half a century ago or just last year.

Unexpectedly, I found this to be the most moving moment of the entire pilgrimage, a reminder of our own brief walk through the storms of life and a changing universe. Wendy was kind enough to take a photograph of it.

The rain mercifully followed us to Siena and Rome, where the skies cleared, the sun bobbed out, the heat returned and the summer tourists swarmed over the Vatican and its celebrated museums.

I bailed out halfway on the official Vatican tour, feeling as oppressed by the grandeur of monumental Rome as the holy relics of Old Jerusalem, concluding I must either be a poor excuse for a Christian pilgrim or a true country mouse.

Back home, I had a friend who is a gifted artist secretly paint the abandoned farmhouse, and gave it to my wife for Christmas.

She loved the painting but joked that it was really for me. I couldn’t disagree, pointing out that I also gave myself a new Expedition watch for our next pilgrimage. PS

Contact Editor Jim Dodson at jim@thepilot.com.