Outdoors Is Not Closed

A gift that amazes the child in all of us

By Clyde Edgerton

I’m writing these words in late March 2020.

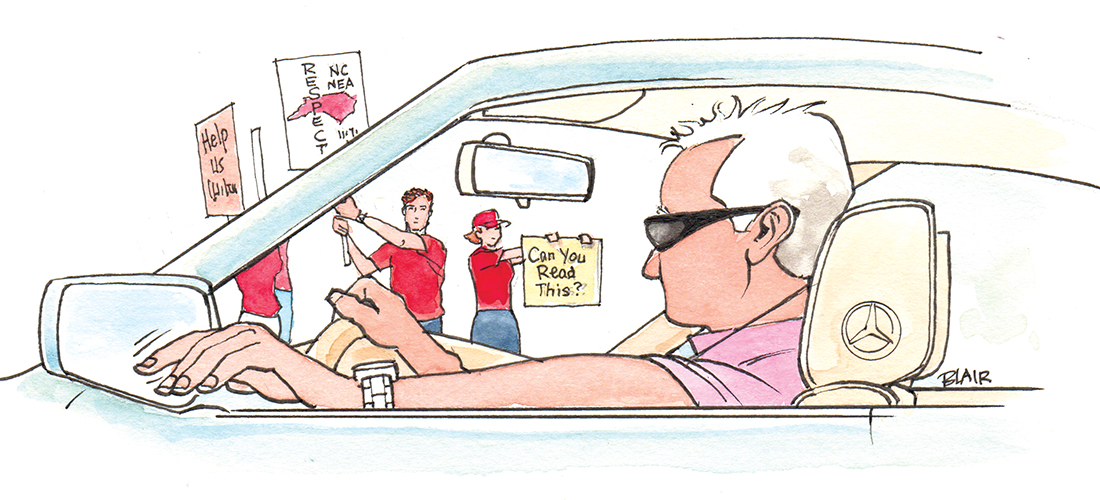

My gentle editor recently told me that the Salt magazine theme for May’s issue would be “the outdoors.” I took a walk to think about how to write about that subject during these dark times.

More people are taking walks, riding bicycles — missing beaches and closed parks. I can only guess at how things will be in early May, when you are (now) reading these words. It does not seem far-fetched to guess that, by then, you or I — or both of us — will have lost people we knew, and perhaps loved. I know of no time since World War II during which I could have said that.

On my walk, I notice a wisteria vine behind a neighbor’s house. I think about how, unchecked, it will begin to take over bushes, shrubs, trees — a nuisance vine. But the beauty of its blossom may counter that, depending on your relationship to the vine; that is, if it’s growing in the woods you can admire it, but in your yard it may become invasive and unwelcomed. The reason I notice the vine on this walk is because late March and early April are days of Wilmington’s wisteria blooming — light purple — for its three- or four-week colorful span.

I rarely, if ever, see a wisteria vine without remembering a particular wisteria vine. My mother remembered it being planted in about 1915 at the base of a trellis in her grandmother’s backyard. That would have been three years before the Spanish flu epidemic. Twenty-one years later, in 1936, the federal government bought 5,000 acres in the vicinity of the homeplace, where the vine grew on its trellis, and offered it to the state of North Carolina for a dollar, with the understanding that the acreage would become a recreational site. The site became the William B. Umstead State Park, situated between Raleigh and Durham. Graveyards, as well as stone and glass remnants of an entire community, can still be found near trails and streams.

The wisteria vine planted by my grandmother survived the land transfer, and once every year for the past 70 years or so, I’ve helped family members clean the family graveyard near the site of the homeplace. By the 1950s, the wisteria vine began taking over wild shrubs and pine trees around the graveyard, and for a while in the early ’80s it arched magnificently over a dirt road that ran through the park. This memory of it in bloom, reaching up into and over pine trees, and over the road, is unforgettable. Park rangers painstakingly extinguished the vine in the 1990s. Sadly, in my view.

My guess is that you remember an outdoor childhood spot — near a certain tree, or creek or hillside. Perhaps there was a path that led to a secret place. While outdoors interests adults, it often amazes children. When did you last climb a tree?

In a sense, outdoors is childhood. And outdoors is a gift, like a sense of humor, like strong relationships with people we like and love. Gifts. Not acquisitions growing from what we don’t need.

Granted, we need toilet paper, but it’s not free.

Outdoors is free. PS

Clyde Edgerton is the author of 10 novels, a memoir and most recently, Papadaddy’s Book for New Fathers. He is the Thomas S. Kenan III Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing at UNCW.