The tournament that took a fortnight to finish

By Bill Case • Photographs from the Tufts Archives

The Diamondhead Corporation’s 1970 acquisition of the Pinehurst Resort complex, hotels and 6,700 undeveloped, mostly wooded acres from the Tufts family brought about a dramatic transformation of the entire community. To replace the Tufts family’s vision of Pinehurst as an idyllic and peaceful New England-style community where the elite from the North golfed and hobnobbed with one another for months at a time, Diamondhead instituted a new go-getter business model, which executives imported by the company from the West Coast fondly called “California brass.”

Diamondhead spent millions updating the venerable Carolina Hotel, rechristening it the Pinehurst Hotel. A hard push began to attract conventions, an approach the Tufts family had historically disfavored, fearing it would drive away valued longtime patrons. Huge chunks of forested acreage were subdivided for sale as residential lots and condominiums. Like spring dandelions, new homes bordering golf course fairways appeared overnight. The properties were marketed with such frenzy that a writer for The Pilot observed that Diamondhead’s sales force clustered on the prime lots “with the intensity of ants on a piece of picnic pie.” Pinehurst’s old guard residents, including the Tufts family, were mostly appalled. The perceived arrogance of cocksure Diamondhead executives, inclined to adorn themselves in California-cool gold chains and leisure suits, exacerbated the friction.

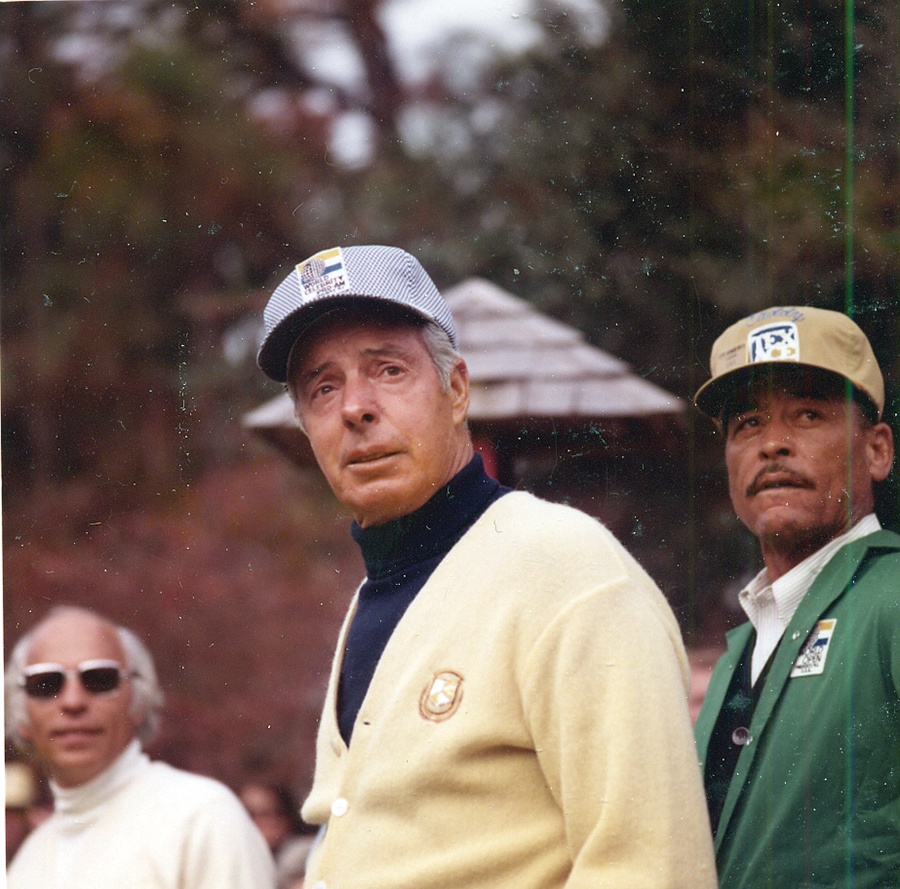

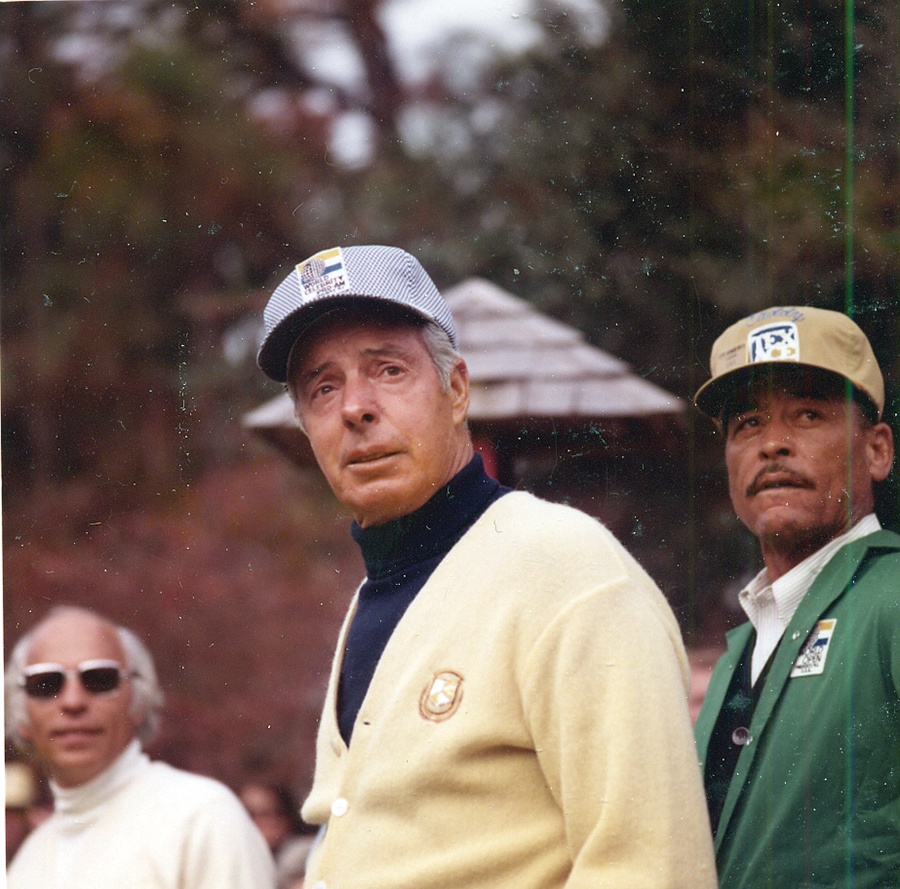

The man overseeing this metamorphosis of everything Pinehurst was Diamondhead’s president, Bill Maurer. The dour, hard-driving former golf pro had been selected as front man for the operation by Malcolm McLean, the mega-wealthy tycoon financing the Diamondhead purchase. Keenly aware that Pinehurst was America’s foremost golfing Mecca, Maurer believed dramatic steps were in order to ramp up the resort’s identification with the game.

Maurer could not be faulted for failing to aim high. He envisioned a modernized Pinehurst firmly branded in the public’s mind as the undisputed “Golf Capital of the World.” He convinced McLean to invest $2,500,000 for establishing a hall of fame for golf behind the fourth green of the No. 2 course. Explaining his thinking in an interview with Country Club Golfer, Maurer said, “I’ve read for 20 years about all these different plans to build one (a golf hall of fame). None of them has ever come to a hill of beans, and I don’t mean that unkindly. It’s just a lot of conversation and lip service. I think if we own and operate the World Golf Hall of Fame, it would not only be good for Diamondhead’s image and its place in the golf world, but also it would be a real good attraction for golf and Pinehurst.”

Pinehurst had not hosted any professional golf tournaments since 1951, when Richard Tufts became disenchanted by the behavior of the U.S. team in that year’s Ryder Cup matches played over Pinehurst No. 2. Tufts canceled the prestigious North and South Open. Maurer considered Richard’s banishment of the pros a tragic mistake and decided that, given the fast-growing popularity of the PGA Tour, pro golf should return to the resort. But Maurer had no interest in hosting just any tournament. As he put it, “If it is the golf capital of the world, let’s really make it that. Let’s have . . . the World Championship.”

Maurer persuaded McLean that to hold a true world championship, prize money commensurate with that title should be part of the package. McLean agreed to bankroll the largest purse the game had yet seen — $100,000 to the winner and $500,000 total prize money. But Maurer needed to convince Joe Dey, executive director of the Tournament Players Division, that his audacious proposal was viable. Complicating matters was his desire that the World Open be contested over eight rounds, twice the customary number. Two weeks would be necessary. Maurer also sought the inclusion of numerous foreign players to underscore the tournament as a truly worldwide championship.

A year of sporadic discussions with Dey ensued before Diamondhead’s president finally made headway. In January 1973, it was announced that the World Open Championship would be played in Pinehurst, commencing Nov. 5 and ending the 17th. While concerned that Pinehurst’s late autumn weather could pose a problem, Maurer liked the idea of crowning the “world champion” at the tail end of the season.

Maurer contemplated a gigantic field of 240 players. After an 18-hole celebrity pro-am, the first four rounds of the tournament would be contested over No. 2 and No. 4 with competitors making two circuits of each. After completion of Sunday’s fourth round, the field would be trimmed to the low 70 players and ties. Contrary to usual tour practice, players falling short of the cut line would be paid $500. The survivors would take a two-day break before resuming play on Wednesday. Course No. 2 would serve as the exclusive venue for the final four rounds, culminating in an unusual Saturday finish.

Mindful that Pinehurst had not hosted a pro tournament in over two decades, Maurer assembled a new team for the task. Likeable and garrulous Tennessean Hubie Smith, 1969’s Club Professional of the Year, came on board as tournament director. Another club pro, Don Collett, was hired as president of Pinehurst, Inc. That post involved an imposing array of duties that included managing all operations of the Pinehurst Country Club and jumpstarting the embryonic Hall of Fame.

It was determined that Course No. 4 should be toughened to pose a challenge for the likes of Jack Nicklaus, Lee Trevino and other tour stars. Diamondhead retained famed architect Robert Trent Jones Sr. to perform an overhaul of the course. With Jones swiftly working in tandem with club superintendent Dick Silvar, the updating was completed in only 90 days. A pleased Jones expressed satisfaction with his handiwork, proclaiming that No. 4 would soon be recognized as “one of the great courses of the world.”

Diamondhead enticed baseball great Joe DiMaggio to serve as celebrity host for Wednesday’s “Joe DiMaggio World Celebrity Pro-Amateur.” Accepting invitations to join Joltin’ Joe on the tee were A-list celebrities like Bing Crosby, James Garner, Fred MacMurray and Stan Musial. Licking their respective chops at the opportunity to take down the tour’s largest-ever payday, the circuit’s rank-and-file sent in their entries faster than the deal at a Vegas blackjack table. As tour mainstay Miller Barber put it, “nearly everybody who can hit the ground with a golf club” was headed to Pinehurst. This included a number of players a decade or more past their primes who nonetheless looked for a last hurrah.

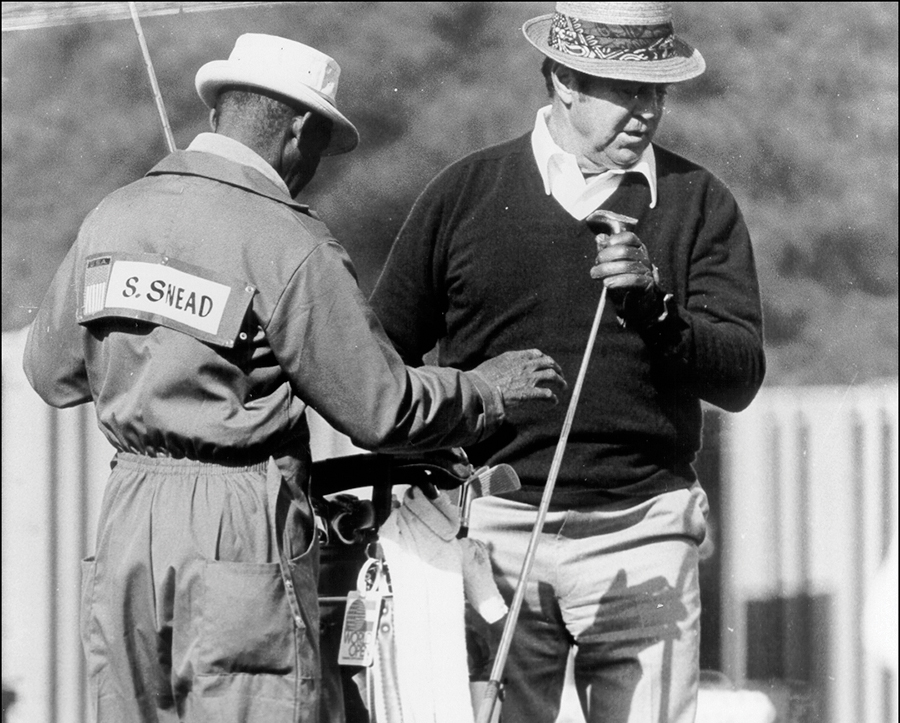

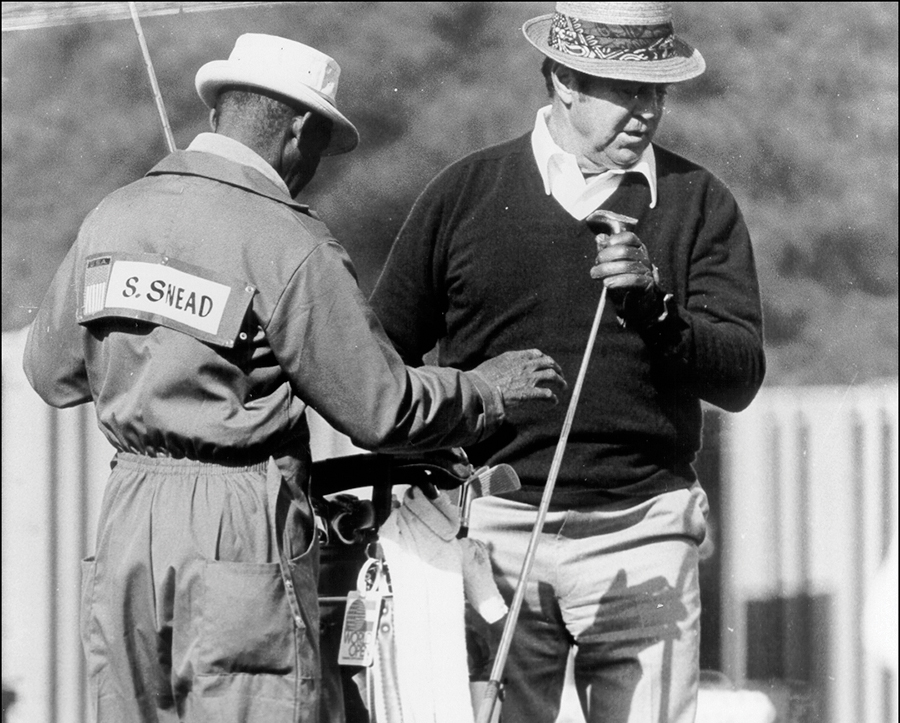

Assuming that the combination of record prize money, an impressive-sounding title and Pinehurst No. 2 would prove irresistible to the tour elite, Maurer failed to take into account that the players most likely to be unimpressed would be the upper crust champions whose winnings and endorsement income had already placed them in a position where they could afford to say no. Jack Nicklaus, winner of the ’73 PGA Championship, sent his regrets. He wanted to spend time with his family and rest up for the World Cup in Spain, where he would pair with Johnny Miller as the American team. Miller had planned to compete in Pinehurst, but ultimately withdrew. The ’73 British Open champion, Tom Weiskopf, begged off, opting to hunt for big game. England’s Tony Jacklin, a two-time major champion, couldn’t come because of a scheduling conflict in Japan. Trevino expressed a lack of interest for playing in a two-week tournament in chilly weather. Still, Arnold Palmer, Gary Player, Billy Casper, Hubie Green, the ageless and still competitive Sam Snead, Masters champion Tommy Aaron, and rising stars Tom Watson and Ben Crenshaw were all entered. But the absences of Nicklaus, Miller, Weiskopf, Jacklin and Trevino doomed hopes of a nationally televised World Open, a big blow to the Diamondhead execs.

Though Maurer couldn’t hide his disappointment, the absence of a few champions worked in favor of the remaining players who descended upon the area for their Monday and Tuesday practice rounds. The hotels and inns received plenty of patronage. Players with limited budgets sought more cost-effective arrangements. Tour newbies Don Padgett Jr. and Andy North arranged affordable lodgings outside Pinehurst, finding an inexpensive condominium adjacent to the Hyland Hills golf course, then nearing completion. The owner let the rookies practice on the range of the unopened course. Padgett and North shagged their own balls.

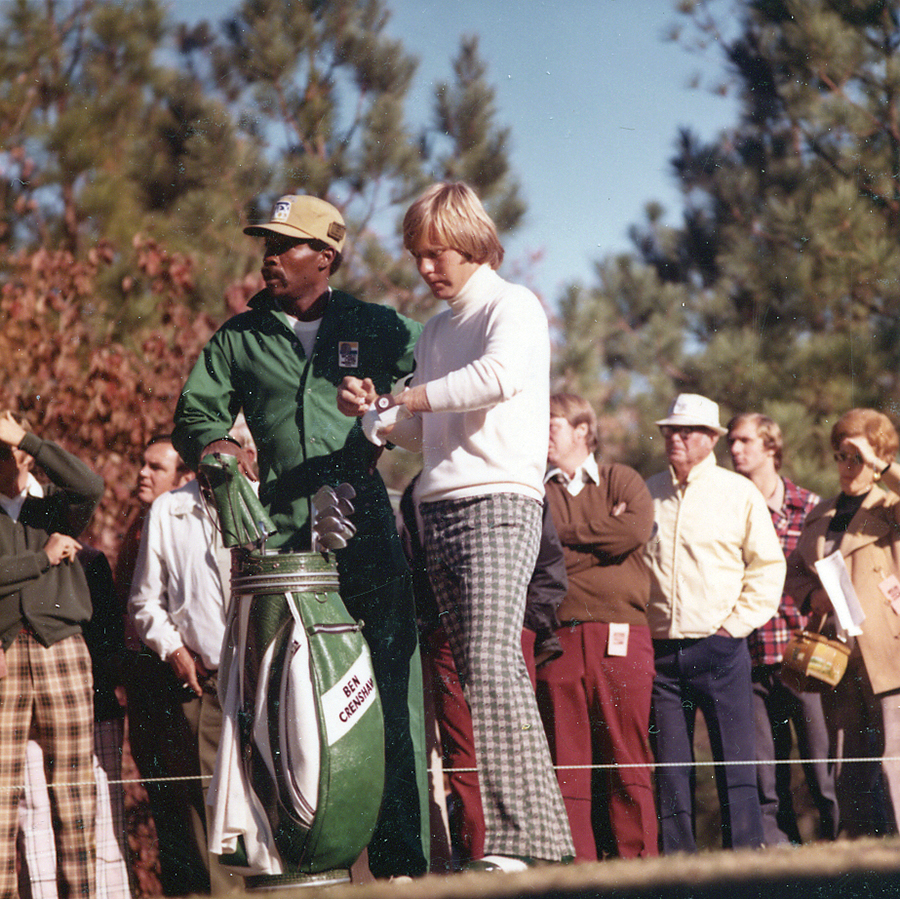

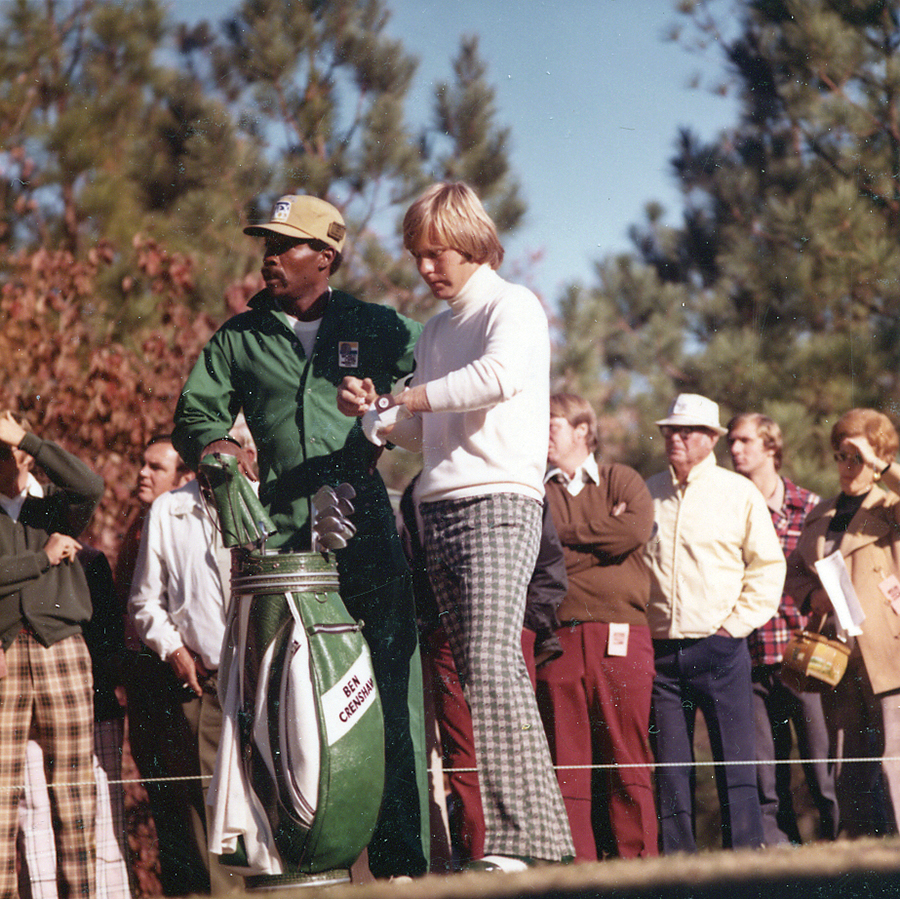

Some lucky young competitors benefited from free housing. Peter Tufts, Richard’s son, resided on Fields Road less than 200 yards from the second hole of No. 2. As the builder and course architect for the nearly completed Seven Lakes Country Club, Peter was a respected force in golf. He possessed a soft spot for young players trying to make their way, and opened up his home to four of them, none older than 25: John Mahaffey, who had won the Sahara Invitational the previous month and would five years hence become PGA champion; Pensacola’s Allen Miller, who would win once on tour; Eddie Pearce, predicted by many knowledgeable insiders to be the “next Nicklaus”; and 21-year-old Texan Ben Crenshaw, a three-time NCAA individual champion from the University of Texas who had turned pro shortly before the World Open and immediately made hurricane-force impact. He emerged from the grind of the PGA Tour’s qualifying school as its runaway winner by 12 shots, then captured his first tour event, the San-Antonio-Texas Open, shooting 14 under par. If Crenshaw won in Pinehurst, he would become the first player ever to win his first two tour events.

Peter Tufts’ wide-eyed 14-year-old son, Ricky, was excited these young golf stars were bunking at his home. They were funny, teased each other and laughed so loudly that Pete implored them to keep the noise down. Rick Tufts, now a retired firefighter, recalls that the young pros included him in their hijinks, considering the pros his big brothers for the fortnight.

One subject of their banter was Ricky’s predicament in obtaining transportation to his part-time job in Seven Lakes. The teenager wanted a motorbike, but Dad was unwilling to spring for its purchase. That brought about a chorus of guffaws from the houseguests who kiddingly razzed “Tightwad Pete.” Finally, Crenshaw promised that if he should win the World Open, he’d buy the motorbike for Ricky himself. Thus, Ben’s “little brother” became an avid cheerleader for a Crenshaw triumph.

A minor kerfuffle occurred when DiMaggio arrived. Thinking his name would be associated with the main tournament (something like the Joe DiMaggio World Open) instead of just the pro-am, Joltin’ Joe was quite put out after learning of this misunderstanding. The Yankee great could be glowering and sullen when angry, and that was the last thing Maurer needed to kick off the festivities. Concerns about DiMaggio’s reaction were heightened by the presence of the foreboding fellows accompanying him, both of whom could have been typecast as Corleone button men in The Godfather. But if Joe was upset, he managed to hide his displeasure interacting with Crosby, Garner and comedian Foster Brooks.

Frigid weather descended on Thursday’s first round with temperatures in the 30s and ice visible in the bunkers. Spectators stayed away in droves. Padgett, who years later served as Pinehurst Country Club’s president and chief operating officer, felt like a sled dog in the Iditarod. One of the early starters, when he reached his opening drive, he recalls, “There was so much ice on the ball, it looked like a snow cone.” Padgett implored a rules official for relief but was denied. Bob Goalby, then 44, still remembers the miserable weather. “It was thermal gloves off for your shot and then on again as quickly as possible — anything to stay warm,” recollects the 1968 Masters champion.

Starting off both nines of two different courses caused confusion for several players. Eddie Merrins never left the starting gate, having appeared for his tee time on the wrong course, he was disqualified, retreating to the warmth of the clubhouse. A few players seemed unaffected by the conditions, most notably Gibby Gilbert. Playing with Snead on the back nine of No. 2, the Chattanooga product birdied two holes and chipped in for eagle on 16 for an eye-popping 32. A remarkable string of five birdies on the front nine brought Gilbert in with a 62, shattering Ben Hogan’s course record of 65. The astounding round gave Gilbert a 5-shot lead over his closest pursuer (and one of Ricky Tufts’ buddies) Allen Miller, whose 67 came on No. 4.

Despite this stellar round, Miller leveled sharp criticism of the recently renovated No. 4. “The course scares me,” he confided to Golf World editor-in-chief Dick Taylor. “It’s harder than No. 2. I don’t cherish playing it. No. 4 is tougher in an unfair way.” Miller was not alone in this view. There was “almost unanimous chorus of dissent over Trent Jones’ remodeling,” wrote Taylor.

Meanwhile, two of Miller’s three housemates finished respectably with Mahaffey and Pearce carding 72s. Lagging was a frustrated Crenshaw, who opened with a desultory 75. One tour veteran — chilled to the bone and disgusted with his awful round — sought a way to pocket the $500 missed-cut stipend without completing the four rounds officials expected. He found a previously overlooked loophole in tournament rules that permitted an early escape. A player needed only to start the tournament to be entitled to the $500 for non-qualifiers. Once this information became common knowledge in the locker room, withdrawals by players off to poor starts flooded in. In all, 41 players said early goodbyes.

After an even chillier round two, Gilbert still led but had come back to the field some with a 74. Ron Cerrudo and Miller lurked two shots back. Crenshaw improved with a 71, but still trailed Gilbert by 10. Gilbert kept his nose out in front through Sunday’s fourth round. His 280 total at the endurance test’s mid-point led the field by 5. Al Geiberger and Tom Watson surfaced as the closest challengers, with Watson crafting a couple of rare sub-70 rounds of 69 and 68 over the weekend. Among those surviving to play week two were Palmer, Player, Goalby and the amazing Snead, guided by caddie Jimmy Steed, unfailingly employed by Snead whenever he was in Pinehurst. Miller’s housemates all made the cut, but were too far back to harbor realistic hopes of victory. Crenshaw’s 294 trailed by 14. Ricky Tufts’ hopes for his motorbike seemed irretrievably dashed.

No logistical reason existed for the World Open’s two-day layoff. Peter deYoung (then the assistant tournament director and still a Pinehurst resident active in organizing youth golf tournaments) remembers that the only thing the committee needed to do during the break was move a bank of port-o-potties and a lone concession stand from No. 4 to No. 2. The departure from the pros’ normal tournament routines perplexed some of them. Crenshaw says that the mid-tournament delay “was surreal. We weren’t sure what to do.” Crenshaw, Pearce and Mahaffey wound up playing Pine Needles with Golf World writers. The 61-year-old Snead, who liked nothing better than hitting golf balls, practiced both days. A few players visited the temporary home of the World Golf Hall of Fame on West Village Green Road, now occupied by a Bank of America branch. Miller remembers a nighttime visit to Pinehurst’s Dunes Club, which featured unauthorized drinking and gambling in the back room. Miller was among those forced to vacate when management was tipped off to an imminent raid.

As temperatures warmed for the fifth round, the tournament leader’s game plunged into a deep freeze. No. 2 exacted its revenge on Gilbert, who shot 82 — 20 strokes higher than his round one course record. Broadcaster and Pinehurst sage John Derr had predicted that Gilbert’s scintillating opening 62 “would never be duplicated” on No. 2, but just six days later, Watson proved him wrong. Canning lengthy putts from outrageous distances, Watson vaulted to a commanding lead with his own 62. Tied for second, but nine strokes back, were Bobby Mitchell and 42-year-old veteran Miller Barber. Allen Miller fell to 14 shots behind, but still led Crenshaw whose 71 kept him in the tournament’s backwater, a seemingly insurmountable 18 strokes behind Watson.

Despite high winds in round six, Crenshaw roared back from oblivion. Striking his irons so solidly that his shots never wavered in the gale, he carved out a 64 that some observers deemed superior to the 62s of Gilbert and Watson. Crenshaw, twice a Masters champion, still considers this one of his greatest rounds. News of the fantastic score rapidly circulated all over the course. Not only had he bypassed his fellow houseguests, he leapfrogged all but Watson, joining Jerry Heard and Barber in second. Watson delivered a wobbly 76 but remained six shots ahead. After another unsteady 76 by Watson in the seventh round, his challengers loomed closer with Barber and Mitchell poised only two back and the resurgent Crenshaw three.

It felt to players teeing off in the eighth and final round, that they had been competing in the World Open for months. According to Golf World’s Taylor, Al Geiberger kidded his playing partners on one hole, “If I remember correctly, I hit a 4-iron here in April during the 23rd round.” Exhausted tournament volunteers couldn’t wait to attend “End of the World” parties to celebrate Saturday’s finish.

Watson promised Pinehurst friends he would throw a party himself if he won, but a disappointing 77 would drop him into a fourth-place tie. It looked as though the winner would emerge from the Crenshaw/Barber pairing. Twice Crenshaw’s age, the balding, paunchy Miller outweighed his young rival by nearly 50 pounds. The svelte Crenshaw with his long blonde locks had already become a charismatic heartthrob. An odd couple then, Crenshaw recalls Barber, who died in 2013, with deep respect and affection. “I loved that man,” he says. “He was one of those guys who was funny without trying to be.” With his dark sunglasses, his steadfast refusal to reveal his nighttime whereabouts and his parabolic backswing, “The Mysterious Mr. X” acquired a colorful mystique that belied his unprepossessing personal appearance.

Barber and Crenshaw dueled back and forth exchanging birdies and bogeys until Mr. X birdied the 14th to take a one-shot lead. At the par-5 16th Crenshaw swung out of his shoes and pulled his tee shot far left into the woods. Unable to recover, he bogeyed the hole to fall two back. According to Crenshaw, golf writer and Pinehurst bon vivant Bob Drum later asked him, “What were you trying to do, drive the green?”

After Barber laced an iron into the heart of the green on the par-3 17th, he turned to rotund caddie Herman Mitchell (who would become better known in coming years as Trevino’s caddie) and exclaimed, “That’s it!” He parred that hole, and then put the icing on the cake by rolling in a closing birdie on 18 to defeat Crenshaw by three.

One would think Barber would pause at least for a moment to bask in triumphant glory. According to deYoung, however, he had another agenda. “Peter, come here,” commanded Barber. “I’m not going to the pressroom. Get me a bourbon and one writer and I’ll give him 20 minutes.” He needed to catch a plane to Dallas for a Cowboys game the next day. With the hasty interview concluded and desperate to flee the place he’d been for almost two weeks, Barber waited in the parking lot for his caddie. Ladened with golf equipment, a harried Mitchell lost control of the shag bag and the balls spilled out, running to the far corners of the parking lot like a pack of children playing hide-and-seek. “Forget them, Herman,” ordered Barber. “Let’s go!” So exited golf’s inaugural world champion.

Crenshaw’s disappointment was salved by his $44,175 second-place check. “All of a sudden I had some money,” he says. “And every bit of success helps a player searching for confidence.”

Forty years later Crenshaw would return, along with his partner, Bill Coore, to restore No. 2. His 1973 World Open experience “stimulated my love for Pinehurst,” which, as he sees it, “came full circle.” Rick Tufts may have been forced to finance his motorbike, but he gained a lifetime friend. He still exchanges Christmas cards with Crenshaw and enjoyed a sentimental reunion with him during the 1999 U.S. Open.

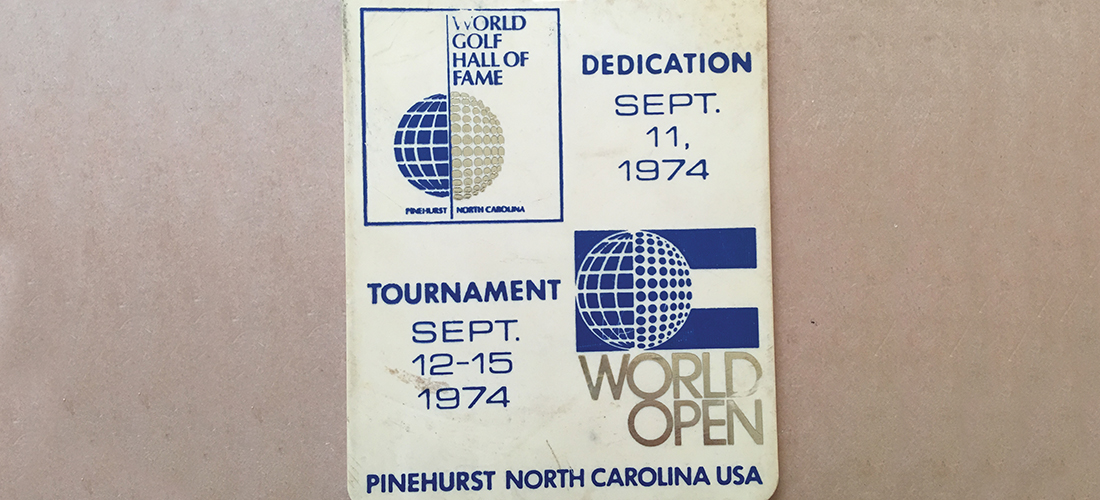

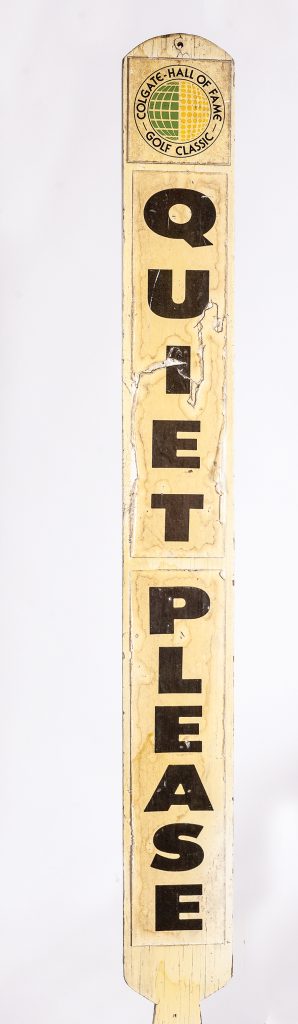

Downbeat over low attendance and the absence of stars, Maurer had nonetheless committed to host the World Open for two years. The tournament was shortened to 72 holes with a commensurate reduction in prize money. The PGA Tour granted Pinehurst a more hospitable week in September to coincide with the opening of the new World Golf Hall of Fame building and the Hall’s induction ceremony. September 11, 1974 marked one of the most memorable days in Pinehurst’s golfing history with Ben Hogan, Byron Nelson, Sam Snead, Gene Sarazen, Gary Player, Jack Nicklaus, Arnold Palmer and Patty Berg all on hand for their respective inductions and President Gerald Ford was in attendance as well. Johnny Miller won that year’s tournament. Nicklaus would capture the event in 1975. Diamondhead would sign Colgate as the corporate sponsor beginning in 1977 and the event was renamed the Colgate Hall of Fame Golf Classic. Colgate dropped its sponsorship after 1979. Pinehurst ended its 10-year run as an annual tour stop after the 1982 event. Born as a marathon, conceived as a curiosity, it became a 144-hole footnote to the history yet to come. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.