It’s off to work we go

Illustrations by Laurel Holden

We’ve all had ’em, those odd jobs we’ve done along the way. Maybe it was behind a cash register or in front of a deep fat fryer. It could have been sweeping floors, pouring concrete or delivering pizza. The uniform might have featured a hairnet or a pair of work boots. It could have been weekends or evenings in high school or a long, hot summer waiting for college to begin. Maybe you already had a degree in your hand. The payoff could have been cash money (though not much of it) or nothing more than the experience. The memory of these jobs can bring a smile, a groan or a grimace. The money, if there was any, didn’t last long. The lesson that all work is noble lasts a lifetime.

Helen Buchholz is the mother of eight and grandmother of 25 who just celebrated her 95th birthday and once owned The Salem Shop, a women’s apparel store located on the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and S.W. Broad Street. At home she has a photograph taken during War War II of her husband, John, who lost a leg in the Battle of Peleliu, meeting Bing Crosby at a golf club outside of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She was Crosby’s driver and, at the time, didn’t know the man who would become her husband.

“I was a driver for the Emergency Aid in Philadelphia. An organization of volunteers. I did it from 1941 to 1945. I was 18 in ’41. My husband got to do it because he was part of the incentive program. They went around to different plants that won the letter E — the flag that they hung on their building — for their work effort. I was the one that drove Bing Crosby. I used to meet them at the airport or the railroad station and take them to Convention Hall when it was a drive for bonds, selling bonds during the war. I drove a lot of them. They had bond drives all the time. Those people came in as guest speakers. They stayed at the Ritz Carlton when it was on Broad Street, if they stayed overnight. I was assigned as their driver the whole time they were there. Most of them were very nice. Some were bossy like they thought we were employees instead of volunteers. They would have somebody in the backseat with them and they’d be talking. Bing Crosby was very nice to us. We had Bob Hope. He was fun. He really was. He had a lot of cuss words in his vocabulary but not like two of the women. Lucille Ball had a very dirty mouth. Linda Darnell. She had a terrible dirty mouth, terrible. That’s what I remember most, I guess. It was all very interesting to me. We were all a bunch of volunteers. We had the USO in the basement of the Academy of Music off Broad Street. The USO was there all day and all night and it was all volunteers that did it. Sometimes there were five or six people down there; sometimes there were 100.”

J.J. Jackson, part owner of the Carolina Hurricanes, has served as a board member and/or chairman of several worldwide rare earths and rare metal mining and natural resources companies; invested in and was a board member of the largest mobile telephone provider in Lithuania; was the chief financial operator of a similar company in Romania; worked for a wireless telecommunications company in the Czech Republic and at a holding company specializing in high-growth, high-risk telecom ventures throughout Central Europe; and on and on. A native of Peterborough, Ontario, and a former hockey goalie who married the Zamboni driver, his wife, Nancy, Jackson and his boyhood friends from Adam Scott High School spent June, July and August with flashlights attached to their baseball caps and old soup or bean cans strapped to their legs with elastic bands wandering local golf courses in the middle of the night learning the ins and outs of business from the ground up.

“I would bicycle about a mile to this guy’s ramshackle house, then we’d pile into some beat-up old van about 10 o’clock at night and drive to a golf course. You’d have a big empty can strapped to each leg like in the old days when you played hockey and used Sears and Roebuck catalogs for shin pads. And then you’d walk the fairway. Your quota was 1,000 worms a night, 500 in each can. Nightcrawlers. You sold them to the bait stores in flats of 500. We’d finish up at 4 or 5 in the morning, get back in the beat-up old van, go back into town, get on my bicycle and pedal back home. One night we were swinging from the limb of a tree and broke it. The golf course was pretty mad about that. Otherwise it was pretty uneventful.”

Paul Murphy is the pastor at Trinity A.M.E. Zion Church and spent a couple of decades performing at the Pinehurst Resort and Country Club.

“Technically, my first real job, I worked for my father, Murphy’s Music Center down in Town and Country shopping center. I moved pianos. Right before going to Chapel Hill to college he sent me off to a piano technicians school in Elyria, Ohio, to learn to tune, rebuild and refinish, everything having to do with a piano. It was called Perkins School of Piano Tuning and Technology. I was there for six months. The guy who owned the place was a West Virginian. He had this little racket going where he would advertise: Junker piano in your basement? They would pay him to rid their basement of these monstrosities. We would get these pianos all the way up the stairs, up on to the truck, bring them to the school, where we would pay him to teach us to tune the pianos and rebuild the pianos. Once the pianos were done then we would deliver them to downtown Cleveland to his store, where he would sell them. For him it was a win-win-win. Once I got to Chapel Hill, I ate up my dinner ticket my first week. When I came to myself, I said, ‘Wait, I can go to the music department and let them know I can tune pianos.’ The first day they sent me down to the basement and I tuned, like, four pianos. I worked my way up to the concert stage. My very first job was down in Madison, Georgia, picking cotton. The next-door neighbors were migrant workers. I was 5. We’d get paid a nickel a week. End of the week, my mother said I could spend three pennies. Go down and get these big round cookies, two for a penny. When we moved to North Carolina in ’71, I was in fifth grade. I got in with the tobacco guys. They were waking up at 4 o’clock in the morning. I think it might have been the summer of my sixth grade year. I would jump on the 4 o’clock truck that would come slowly down the road. That truck was like treasure. You’d hop on the back of it. The guy would throw an old sheet over us because it was still cold, there was still dew in the air and he’d take us way up into the Carthage area and we’d start priming tobacco. I started making 12 bucks a day. Three summers. Oh, my Lord, for us it was fun. They’d give us free grape soda and a pack of Nabs.”

Walter S. Morris III is a doctor. But he wasn’t always.

“Between my junior and senior year at Carolina, I was taking summer classes, but I needed a job. So I went down to Fowler’s Food Store in Chapel Hill, down at the bottom of the hill on Franklin Street. ‘Can I get a job?’ They said, ‘Yeah, we’re looking for a butcher’s assistant.’ I said, ‘Sure, I know a lot about beef and meat.’ I was young and dumb. Fowler’s was great because that was where they had the walk-in beer fridge. That’s why I went down there to apply in the first place. I didn’t get any beer privileges though. It was just to make some money, put gas in the car. Stuff like that. I was driving a silver gray Toyota, one of these little hatchback cars. I had to put my golf clubs through the middle seat just to get them in. Anyway, my job was to slice the deli meats and to clean everything after the day was done. That was the assistant’s job, to clean all the blades and the blood and guts. I did cut my finger once. It was my first trip to the hospital. Actually my second trip to the UNC Hospital because I was born there. I sliced my finger cutting bologna and had this big ol’ drip running down my arm. You remember the bologna that came with the little olives in it? I’m pretty sure that was it. You can’t make that up. I thought, this doesn’t look that much different than the blood I’m cleaning up. I got about four or five stitches for that. I’d never had stitches before. I didn’t know then that I was going to go to medical school — I was sort of pre-med — but after I went to the emergency room I thought, you know, this is pretty cool.”

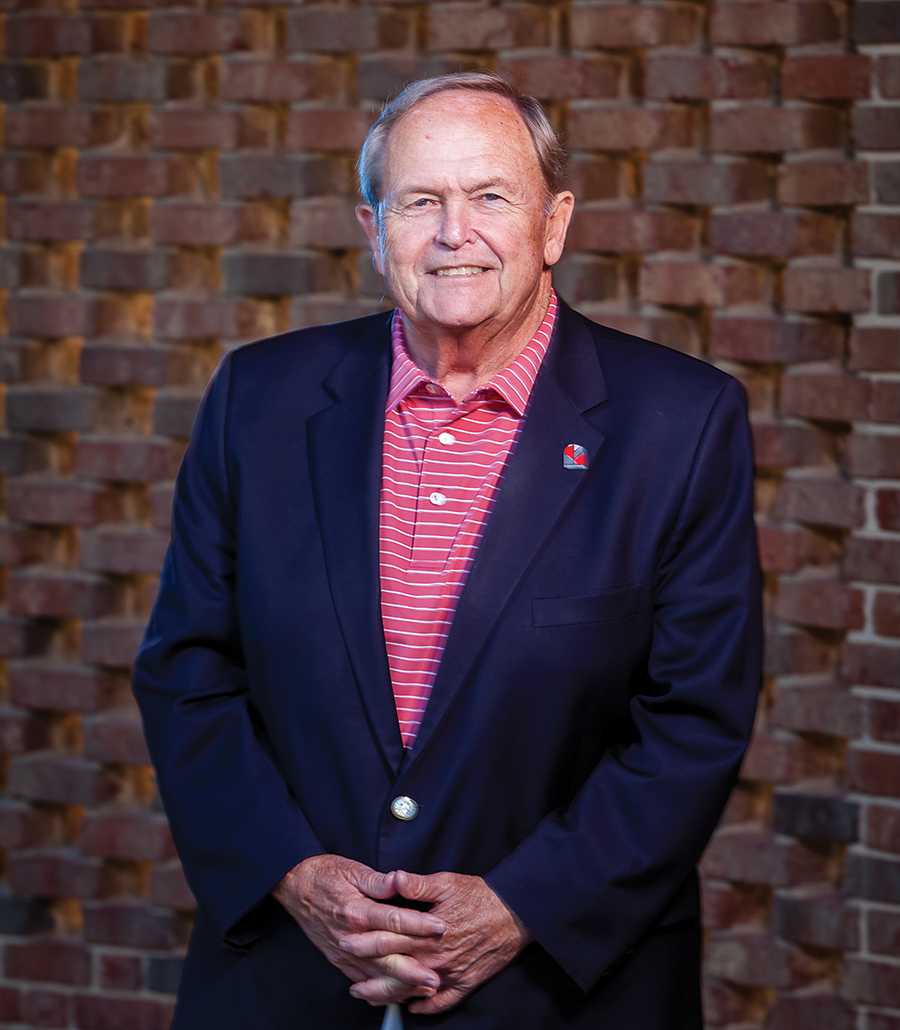

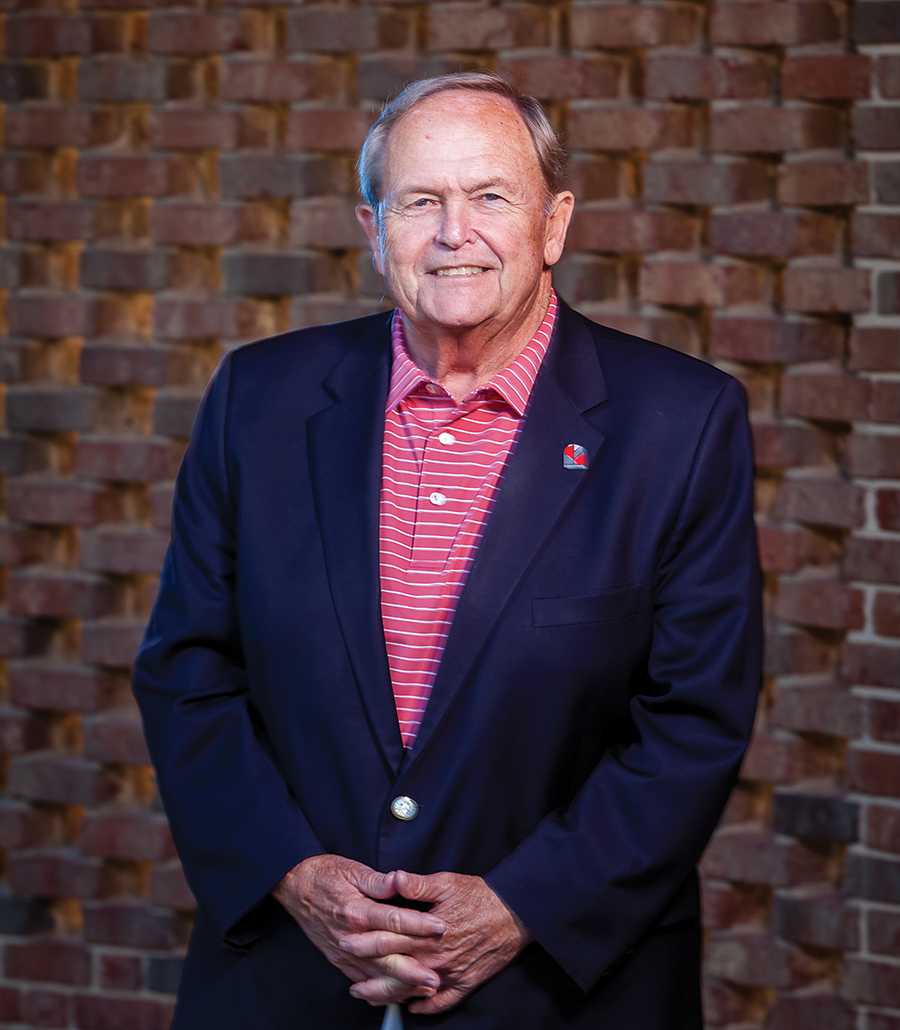

Pat Corso is the executive director of Moore County Partners in Progress and served as the president and CEO of Pinehurst Resort and County Club for 17 years.

“My wife’s sister and I were friends at Ball State University. We were in a group called the University Singers. She had gone to Northern Michigan the summer before and performed at Brownwood Acres, a family business on Torch Lake. The guy that ran it was moving over to a ski and golf resort called Schuss Mountain. She came to me and said, ‘My sisters and I are going to go up and we need a guy. Would you be interested?’ Hell, yes. I was painting fire hydrants in Logansport, Indiana, the summer before. This may be a step up. It was. That’s where I met my wife, Judy. Anyway, we stole music from what we did at Ball State. We’d wait tables. The mainstay entertainment was this guy who played electric accordion and a drummer in the upstairs loft of this ski building. They would play for 40 minutes and invite us up to perform for 20. We’d put our trays down and go up and sing for 20 minutes. The place held 300 and we’d have a line out the door because it was kids, working hard and performing. We did it for three summers. The second year we brought our band up from Ball State and got rid of the accordion player. We played from 9 o’clock at night until 1 o’clock in the morning. They moved me to the door so I was the guy who seated everybody. The girls were called the Schussy Cats. A black leotard, a little barrette with ears on it, hot pink shorts and high boots. I was the lounge lizard — remember shirts with collars that a good wind would pick you up and carry you away? The bottom line is, later on, we opened our own business doing the same thing in Traverse City. We didn’t have anything, didn’t have a nickel to rub together, running around in old beater automobiles, but when you look back at those years, don’t you think, boy, didn’t we have a good time?”

John Dempsey is president of Sandhills Community College. Heck, he’s got a building named for him.

“I got out of the Navy in March of 1971 and I went to graduate school to get a master’s degree at William and Mary. I was on the GI Bill and a little bit of assistantship and we had a little baby. The end of the year came and my GI Bill ran out. My fellowship ran out. So I had no money. I mean, no money. I saw this ad in the paper. Taxicab drivers wanted. What the hell? I went down there. This is early 1972 and I’d gotten out of the Navy in March of 1971 and I hadn’t had a haircut since. Hair was big in ’71. I went in for an interview with the guy and he had a crew cut. He was making a statement just like I was making a statement. ‘I’m here about the taxicab driver’s job,’ I said. He said, ‘We don’t hire girls.’ I was 22 years old, just back from Vietnam. I’ve got two choices. I can jump over the desk and strangle this guy or I can go get my hair cut. I swallowed all my stupid Irish pride and went and got a haircut, came back and got the job. I left the house in the morning looking like a graduate student and I came back that night with a little taxicab driver’s hat on and no hair. The next day was my first day on the job. The deal was, you kept half the proceeds and tips. I discovered very quickly that my customers were not rich. Poor people take taxis because they can’t afford cars. It was unusual to get even a dime tip. I kept all my money in a little sack. The very first night I made $60, so I’d get $30 of it. I had to go to the bathroom at the end of my shift and I went into the Holiday Inn in Williamsburg and I thought I better take this money with me. I left it in the bathroom. Oh, it was so humiliating. That supercilious so-and-so. ‘College student, huh? Can’t even remember . . .’ When you have no money and a little baby you do what you have to do. After that ignominious start, I actually grew to like it. I guess it’s what being a hairdresser must be like. People talk to you about the strangest things. Every once in a while I’d get a call, go to the Williamsburg Inn. You know there’s a tip involved there. I would just schmooze them unmercifully. It got me through the summer. I got my master’s thesis written. You know what it’s done to me? It’s made me a big tipper. I over-tip everywhere I go. I know what it was like.”

Joyce Reehling is an actor and writer, a contributor to both The Pilot and PineStraw and will be appearing in the fall in the Judson Theatre Company production of Love, Loss, and What I Wore.

“The first job I had right out of college was I was Santa’s helper at Sears. I took my Bachelor of Fine Arts and immediately got a job at Sears. The guy in major appliances was Santa, a very nice guy. We took children’s pictures with Polaroids. You took the picture, then you pulled out the thing, then you waved it to make it dry before you put the sealer on it. Then blow on it. This is Sears. There was nothing fancy. I had an elf hat and that’s all. He had kind of this thronie thing for Santa. And then every 30 minutes or so we’d turn the ‘Santa’s Gone to Feed the Reindeer’ sign. And every parent just looked at you like ‘I’m going to kill you now with my bare hands.’ Some kids love to be with Santa. Some kids don’t want to be with Santa at all, ever. I forget how many children peed on Santa. I did this for like 10 days or two weeks. If you can be Santa’s helper for two weeks and not kill either a child or a parent you’ve passed some sort of huge spiritual test. The first job I had in New York was working at a 50-plug switchboard. You take the wires out and push them in. They give you no training for this. Just a headset. The woman who sat next to me was absolutely wonderful. She was very fast, very efficient, you could read every note she ever wrote. She had this darling sweet voice, a Southern voice. She’d answer your phone and you’d think you were the only person in the world, meanwhile she’s doing this for 15 people at the same time. If I got in the weeds, she’d just whip over and pick up a call for me. ‘Oh, baby, I’ll help you.’ It was the Judson Exchange, I think it was called. Behind us was this strange carousel of people who handled almost all the jingle bookings in New York. In the middle of their circle they had like Cheetos and Camel cigarettes. It was a very healthy environment. This was 1970-something. They were always smoking and talking on the phone in these raspy voices. ‘Joe, I got a session. Is this Joe’s wife? Yeah, I got a bookin’ for him. It’s a session plus 20 at 2:30. What? Oh, I’m sorry to hear that. When’s the funeral over? Can he make the 2:30?’ That’s the kind of thing you’d hear behind you.”

The Wisdom of Work

Friends and neighbors recall the peculiar jobs and summer employment that made us who we are today

Baxter Clement, Musician — “I’d just finished college and I went to New York to make music and I had day jobs. For one of my day jobs I dressed up as The Cat in the Hat and read children’s stories in grocery stores in Staten Island. I worked for the Swiffer Corporation, those little mops. Kids would come and sit on my lap, and I was dressed funny and I had a Vanderbilt degree and I was a classical guitar player and I read them stories. I don’t know why they pegged me as The Cat In the Hat but it happened.”

David Carpenter, Accountant — “I was a lint head. I worked in the cotton mill and held the following jobs on any given day: sweeper, card hand, hopper feeder (cotton and polyester), opening cotton bales, comber hand, dye house floor hand, and noil sucker. Before you attached your tube to the vacuum system and flipped the ‘on’ switch, you had to call the waste house and announce what was coming — ‘Mill No. 6, white noils!’”

Sam Walker, Minister — “My first summer job was between high school and college at Phillips Esso just over a bridge off the main drag in Avalon, New Jersey. I can still see the place. Regular gas in those days was 28 cents a gallon. My job was to greet customers, pump gas, wash front and rear windshields, check the oil, the battery, fan belts, radiator fluid and the pressure in all the tires. That summer I learned how to clean restroom toilets, polish brass handles, change oil, lubricate a car, change a flat tire, drive a stick shift, manage a tow truck and that a VW engine was not in the front. I fell in love at least every other week and opened my first bank account. I learned the value of good service, the importance of showing up and doing your job and being part of a team.”

Kevin Drum, Restaurateur — “As a teenager, I was the relish girl at the Pine Crest Inn when the girls didn’t show up. My peers gave me a really hard time but I persevered and tried to be the best relish girl I could be.”

Rose Highland-Sharpe, Minister — “My first semester at UNC-Chapel Hill, I worked at the Carolina Inn. I served the vegetables. I was very nervous about it. I wasn’t much over 100 pounds. A tiny thing back in the day. The fellas referred to me as the ‘Vegetable Girl with the Million Dollar Smile.’ I was so thankful for that job.”

David McNeill, Mayor — “In the ’60s and ’70s the city of Rocky Mount’s largest park, Sunset Park, had a children’s museum, a miniature train, a merry-go-round — or hobby horses as some called them — swimming pool, ball fields, tennis, picnic areas and a concession stand all adjacent to the Tar River. My job at age 16 or 17 was to drive the train and occasionally operate the merry-go-round — with music on LP records. We opened at 2:00 each day and closed at 9:00 p.m., just about dark. I drove the train three times around the half-mile train track for each ticket purchaser — mostly kids. In 1999 the flood after Hurricane Floyd took out the park.”

Rick Dedmond, Lawyer — “I had just graduated from UNC and I needed a summer job. I went to work for my uncle, who was a commercial building contractor, churches, schools, things like that. The first day I was down digging footers to pour concrete. I came back to work the next day and he assigned me to Wallace. For the rest of the summer, I was Wallace’s assistant. Wallace was early 40s, about 6-2, 230 pounds. I’m about 5-6 and I probably weighed about 125 pounds. Wallace wore overalls and a straw hat. Chewed cigar butts after he smoked the cigars. He drove a truck with a dump bed so we mostly cleaned up construction sites. We filled up the truck with sand and bricks and hauled off sheet rock, that sort of thing. We would remove mounds of cardboard where new pews had just been installed in a the church and take it to the cardboard recycling and sell it for enough money to buy our lunch.”

Patrick O’Donnell, Pub Owner — “I took a gap year between Montclair State and Appalachian and I’m backpacking through Cairns, Australia. I was doing willing workers on organic farms. It’s called WWOOF. You call up and say, ‘Hey, do you need anybody?’ You’re working for room and board basically. I had to go clean out the chicken coops. The things were maybe 6-feet high. When you stepped in there it was like 4 1/2 feet. You had to shovel all the chicken shit out and move it to a compost. Oh, my God, this was the worst job ever. I did that for two days.”

Mark Hawkins, Jeweler — “I worked in a convenience store in Miami, Coconut Grove, for maybe six months. That was kind of weird down there at the time. It was probably more dangerous than I realized. I learned how to make jewelry in Coconut Grove. Dropped out of the University of Miami and never looked back.”

Caroline Eddy, Non-profit Director — “Remember the stores The Record Bar? They started in Durham and sold LP albums. I was the clerk that rang up the items we sold. I loved that job.”

Marsh Smith, Lawyer — “My neighbor, Donald Ray Schulte, who was a psychiatrist, lived right across from my dad’s house on Warrior Woods Lake. He had a Jaguar. The road on the north side of the lake was so rough it would knock the muffler off his Jaguar so he ran straight pipes. Every morning he would fire that XKE Jaguar at about 6:15 and have the choke set at fast idle for the motor to warm up. That rumble was my alarm clock. It sold me on the coolness of a Jaguar. A couple, three years later when I was in college I noticed a midnight blue XKE roadster sitting outside Five Points Garage. Carl Bradshaw had a farmhouse off of Highway 211. He had an airplane hangar that had formerly been at Skyline airstrip behind Dunrovin. Carl had a condition that made him allergic to petroleum products. He would sit in his lawn chair and tell us what wrench to choose and what bolt to turn. He agreed to let the Jaguar sit in his garage and I would come home from Duke University and work on it. Then I heard about a guy in Beckley, West Virginia, who rebuilt his Jaguar, so I dropped out of school to go up there and learn about how to restore Jaguars. That lasted a couple of months. I came back and went to work for Carl. I opened up a Jaguar restoration business behind what’s now Doug’s Auto. That building was rented by Lawrence Bachman. He worked on VWs in four of the stalls and rented me one and a half stalls. I lived at the Jefferson Inn, $35 a week for a room, with linens.”

Linda Pearson, Non-profit Director — “I was a cashier at Holly Farms Fried Chicken. It was where Taco Bell is now. I remember my boss’ name was Steve.”

Doug Gill, Lawyer — “The A&W root beer stand on Lincolnway in South Bend, Indiana, was in the form of a giant root beer barrel. I worked behind the counter. My primary job, in addition to climbing up into the attic of the barrel and mixing the root beer in big vats and cleaning the fryer at the end of the evening, was to draw mugs of root beer for the carhops to deliver. On busy nights I was able to draw 12 mugs at a time by holding six mugs in each hand and then rotating them under a running root beer tap. Had I tried to sing, it would have destroyed the business.”

Earl Phipps, Police Chief — “I used to dig ditches for a water and sewer line contractor as a young man working all through Lee, Harnett, Chatham and Moore counties. In college I worked as a vacuum attendant and car detailer at a car wash in Greenville. I used to hate those minivans with the red velvet interior. They always came with a white poodle and its white curly hair stuck in the fabric came along with it. One time I was vacuuming a car and my manager said, ‘Let me know when you are ready for me to pull the car up.’ I answered, ‘OK.’ And he pulled the car up right over my foot. While I was obtaining my Basic Law Enforcement Training I worked as a shoe salesman in the mall. I lived the life of Al Bundy trying to fit size 10 feet into size 7 shoes.”

Rich Angstreich, Proprietor — “In my mid-20s I was a chimney sweep on Long Island. I saw an ad in Mother Earth News. It was this system of cleaning chimneys. You could buy the whole set-up. Home and Hearth. Once you can’t work for other people you’re doomed for the rest of your career to work for yourself.”

Lindsay Rhodes, Shop Owner — “I would handle escalator distress calls and dispatch technicians for Montgomery Kone in Greensboro. Actually it was elevators and escalators. If somebody got their shoelaces stuck in the escalator or got a stroller stuck or if people were stuck in an elevator.”

Tom Stewart, Shop Owner — “Mrs. Mac’s Jelly Kitchen was right downtown in Petoskey, Michigan. Mrs. Mac was probably 75. She would give me a list and I would go to Crago’s Grocery Store and pick up a little thing of half-and-half, Archway molasses cookies and several other things. Before the golf season started she wanted me to weed the flowers. I did such a good job I eliminated every living thing in her plot. She actually used some of that stuff in her jam and her jelly. I don’t think she was real happy. Thank God caddying came along at the right time.”

Jarrett Deerwester, Proprietor — “In Cincinnati I worked for a guy who was a West German immigrant named Willy Brandt. It was a good life lesson. I was a mechanic. The repair shop had white linoleum tile floor. You had to mop it every night. You couldn’t have so much as a screwdriver on your workbench out of place. Complete OCD German. A good first boss. Taught you appearances and details matter. I did that for two years finishing up high school.”

Fenton Wilkinson, Lawyer — “I worked for the Norfolk Redevelopment Management Authority on a brush clearing crew for projects where stuff had overgrown or houses they were going to take down and redevelop.”

Adam Faw, Teacher — “While I was in college I spent two summers working in concrete construction. The first summer I worked at a pre-cast plant in Wall Township, New Jersey. Didn’t need to work out that summer. I got all the exercise I needed lugging things around the plant. The next summer I worked for a concrete company in Boone, North Carolina, mostly in the field on curbing and sidewalk pours. I actually did some steps and railing that are still around campus at Appalachian State.”

Skipper Creed, Judge — “In high school I worked at Goldston’s Beach at the Dairy Queen for one summer. I just wanted to pretty much take the job so my dad would not send me down to his hunting property to work driving a bulldozer or backhoe and getting paid five dollars a day. The great thing about Dairy Queen is you got to see every flavor of life that came by the window. I made thousands of Blizzards. Families would go to White Lake and someone would order for the entire family, including the extended family, because they’re all staying in the different little motels and hotels there. You think they just want one order and they look at you and want 30 banana splits.”

Mark Elliott, Chef — “My dad used to hang me off the side of buildings to fix things. I think I was 11 or 12 years old. We owned a hotel in Torquay. These buildings were huge Victorian summer homes a long time ago. We were repairing the roof, three stories up. It’s like a slate roof with a flat area. He actually had me on a rope wrapped around my feet lowering me down. That is a true story, right there. There was no health and safety back then. We dug out the patio and dug in a pool so it was probably 60 feet to the ground. I remember looking down. My dad would scream, “You’ll be all right, son. I’ve got ya.” I actually got paid 25 pence an hour. That’s about 35 cents. No danger money on that one.”

Kerry Andrews, Marketing — “My only odd job was working in the arcade at a water park in Fayetteville. My friend was a lifeguard but I didn’t quite make the lifeguard status so I got to work in the arcade. They would give me quarters and I would give them tokens. Smelly bunch of 10-year-olds and wet carpet. Back then it was Galaga and Ms. Pac-Man. It was a straight on 1980s arcade with all the ding-ding-ding-ding-ding. Four hour shifts of that.”

Ken Howell, Mason — “My first ever entrepreneurial job was when I was 8, 9, 10 years old and I would buy flower seeds for a nickel in a mail order catalog and sell them for a dime. I’d walk around the neighborhood and sell flower seeds and double my money. After I got in the masonry business I worked at Roses at Christmas putting bicycles together. I would get paid $5 for a regular bike and for a 10-speed I got $10. I would go in there after hours at night, work until midnight throwing those bicycles together. I had to make extra money at Christmas and that was a good way to do it. “

Tom Pashley, Resort Director — My high school job was scooping ice cream at Häagen Dazs. After my sophomore year at college I felt like I needed to branch out. I ended up working for a temporary services company called Kelly and I remember my family saying I was a “Kelly Girl.” Whether or not they were stilling calling themselves Kelly Girls in 1989 or ’90, I don’t know. The job the agency sourced for me was in the Lamar Building in downtown Augusta, Georgia. It’s probably a 25-story building. My job was to paint the stairwells and refinish the wooden banister. There’s nothing like using a paint gun in an enclosed space to teach you the value of education.

Warren Lewis, Chef — “My dad was in real estate and every summer I had to work for one of his contractors. One of the jobs was re-bricking furnaces for big apartment buildings in Manhattan. You got so dirty, your toenails got dirty. The room was the size of a good bathroom with a door that’s like a foot by two feet. You’d climb in. Once you got in the chamber, you didn’t leave it all day. It was relatively cold. You’d have to pull all the bricks out and start re-bricking them. Five bucks an hour. You remember the Moonies, the religious cult? We did their building. They were the coolest people. They would bring us down food and stuff and feed us. We did one in Brooklyn or the Bronx that was really sad. It was a very, very poor neighborhood. They hadn’t had hot water in a year or whatever it was. The landlord finally broke down and had to get it done. These people were angry and sad and happy all at the same time.” PS