Southern Pines’ peaceful integration during the turbulent ’60s

By Bill Case

Though it seems like yesterday for those who lived through it, 50 years have elapsed since the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis, Tennessee. While poignant newsreel footage of racial clashes in places like Montgomery, Selma and Little Rock are enduring images, the struggle to end discrimination extended throughout the South. In Greensboro, a seminal event took place in 1960 when four black students from North Carolina A&T (the Greensboro Four) protested Woolworth’s whites-only lunch counter by refusing to budge from their seats. The success of these sit-ins sparked further civil rights activism in the state, including the “Freedom Riders” bus trips. All of it — and more — gave North Carolina its own share of civil rights heroes. And a number of them hailed from Southern Pines.

While protests against Jim Crow laws and practices — and the reaction to those protests — engendered a degree of hard feelings, the Old North State was spared the racial violence that many areas of the Deep South experienced during the 1960s. The progressive leadership of Terry Sanford, the state’s governor from 1961 to 1965, did much to diffuse tensions. In January 1963, Sanford created the North Carolina Good Neighbor Council to “encourage the employment of qualified people without regard to race, and to encourage youth to become better trained and qualified for employment.” The governor appointed an equal number of whites and blacks to the 20-member council. Later that summer, he urged communities to form similar Good Neighbor Councils to achieve the same goals at the local level.

While not prescribing a specific method for forming those councils, Gov. Sanford’s announcement provided an example of how concerned citizens could get one started. His press release mentioned a unique approach used in Wilson “where a Negro civic club gained the support of the Chamber of Commerce and then the two jointly made a successful appeal to the County Commissioners.”

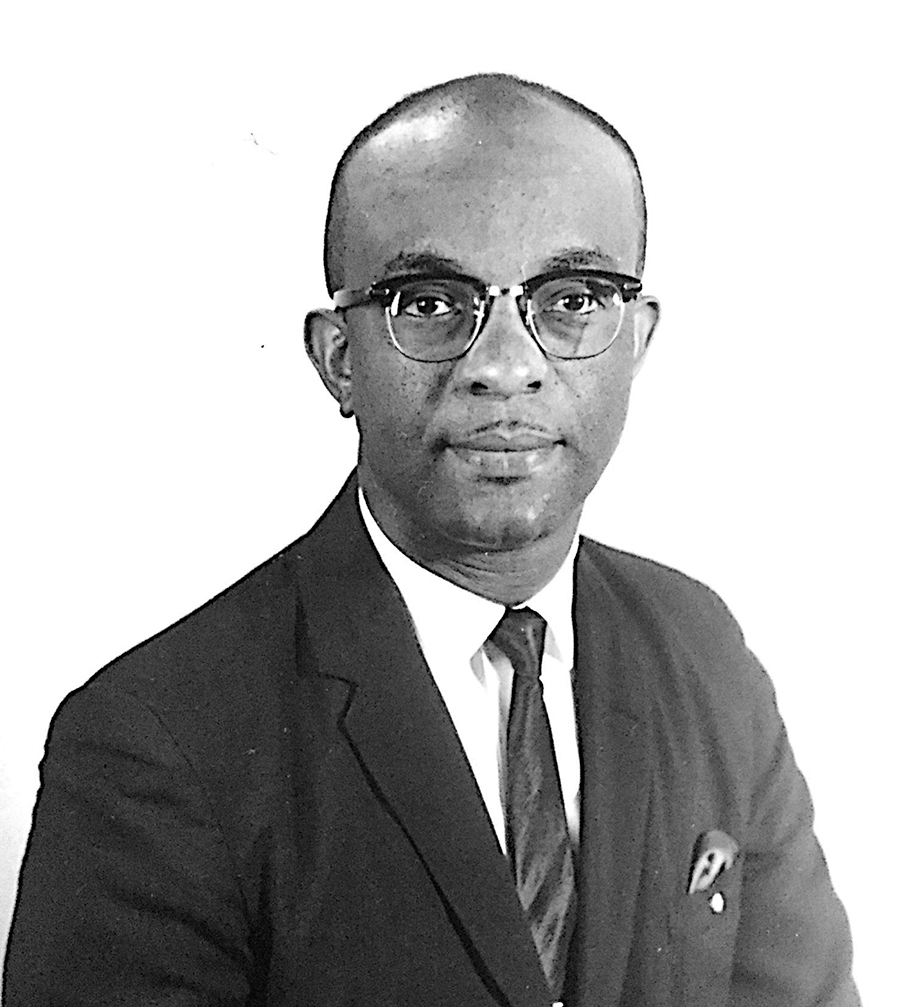

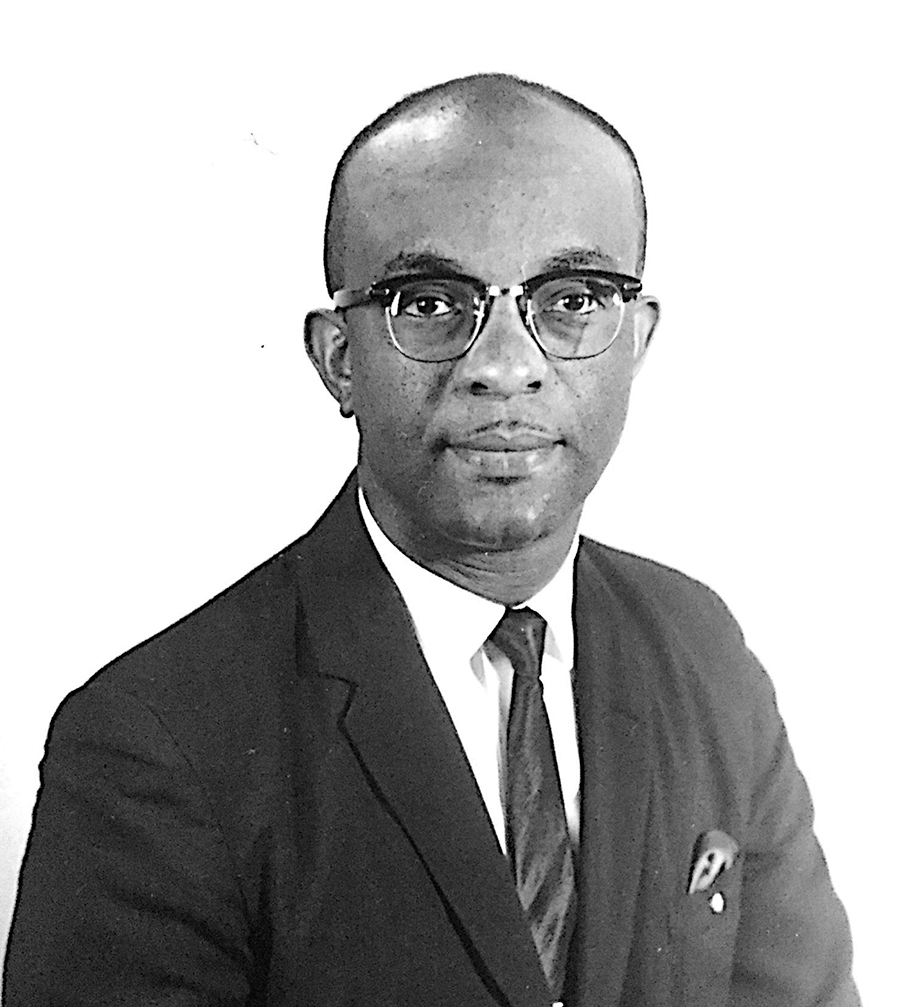

Rev. John W. Peek, then the African-American pastor of West Southern Pines’ Harrington Chapel Free Will Baptist Church, and the president of the West Southern Pines Civic Club, took notice. He thought it would be a good idea for his Civic Club to lead its own effort to end discrimination in Southern Pines. On June 18, 1963, Rev. Peek spoke at a meeting of the Town Council, imploring it to authorize the formation of the Southern Pines Good Neighbor Council “to peacefully meet the demands of the time and work toward the ending of discrimination of race in our community.” According to The Pilot, roughly 75 African-American residents of West Southern Pines, Mayor W. Morris Johnson and councilmen C.A. McLaughlin, Fred Pollard, Norris Hodgkins Jr. and Felton Capel listened intently to Rev. Peek’s presentation.

The pastor acknowledged that progress had been made locally but Southern Pines was still a place where African-American women were not permitted to try on clothing in the two dress shops, and blacks were denied entry to its restaurants. He said racial tension was “widespread” and, to avoid misunderstandings, a Good Neighbor Council would establish a more direct means of communication between the races. The minister summed up by saying, “What the Negro wants is to work at a job he likes, to decide where he wants to dine, to attend cultural, social, and recreation centers, to be admitted to hotels and motels, and to attend the church and school of his choice.”

Peek’s suggestion would have fallen on deaf ears in some communities. Southern Pines wasn’t one of them. The Town Council unanimously approved the formation of a Good Neighbor Council (GNC) with a membership to comprise an equal number of whites and blacks. The Town Council underscored its support for the new group by adopting a resolution confirming the town government’s own policy of non-discrimination, significant because there were no federal or state civil rights laws preventing racial discrimination in employment or access to public accommodations.

Rev. Peek assumed responsibility for appointing the five African-American members to the newly formed GNC. He selected Sally Lawhorne, Iris Moore, Edward Stubbs, Ciscero Carpenter Jr. and himself. Mayor Johnson appointed the following white members: Kathryn Gilmore (then wife of Southern Pines’ former Mayor Voit Gilmore), Harry Chatfield, Robert Cushman, James Hobbs and Rev. Dr. Julian Lake, the minister at Brownson Memorial Presbyterian Church. Though he’d only been in town a matter of months Lake was selected to chair the group and Peek became vice-chair. The appointees came from a variety of backgrounds. “One is an industrialist, two are insurance men, one is in the real estate business, one is a housewife, one a teacher, one a domestic servant, one works in a chain store, and two are ministers, ” said Dr. Lake.

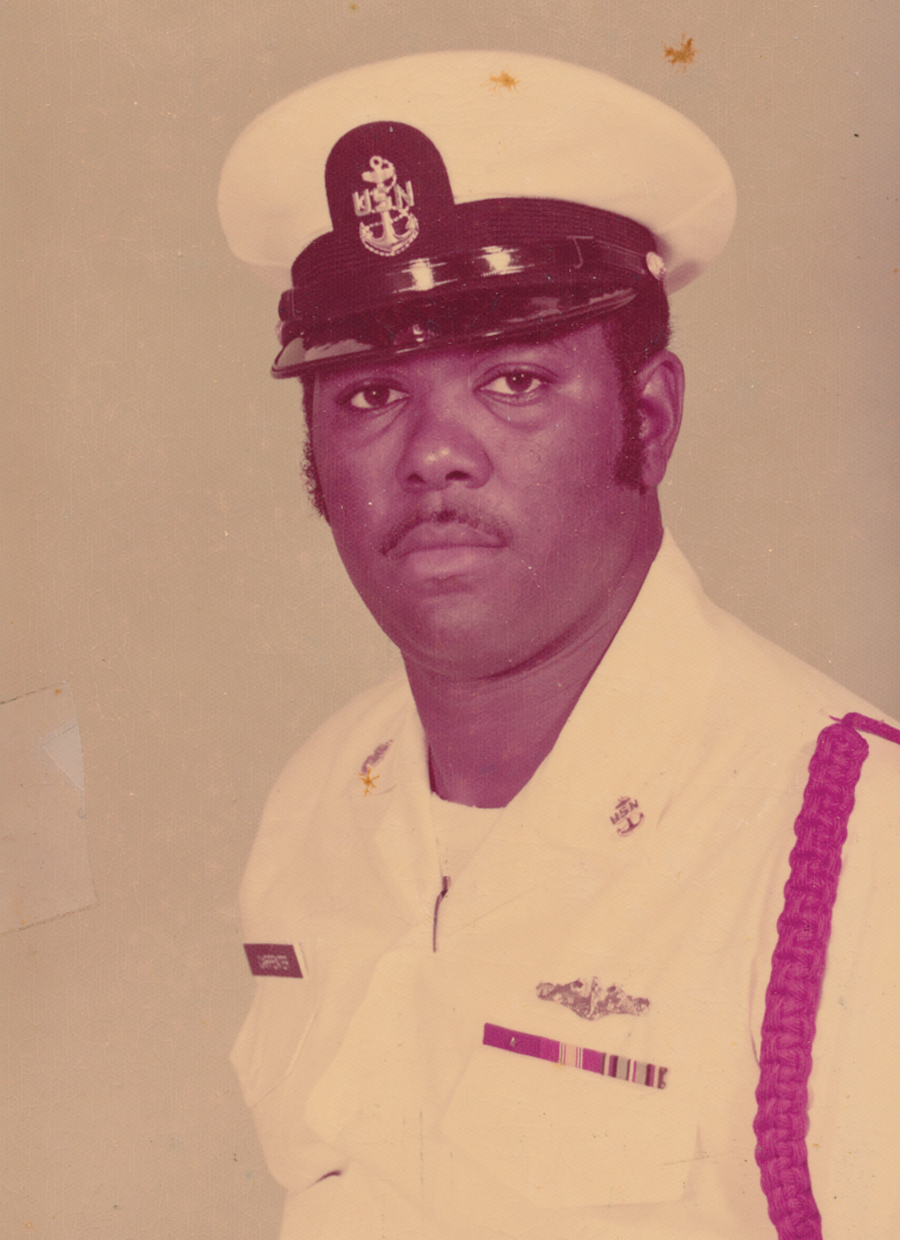

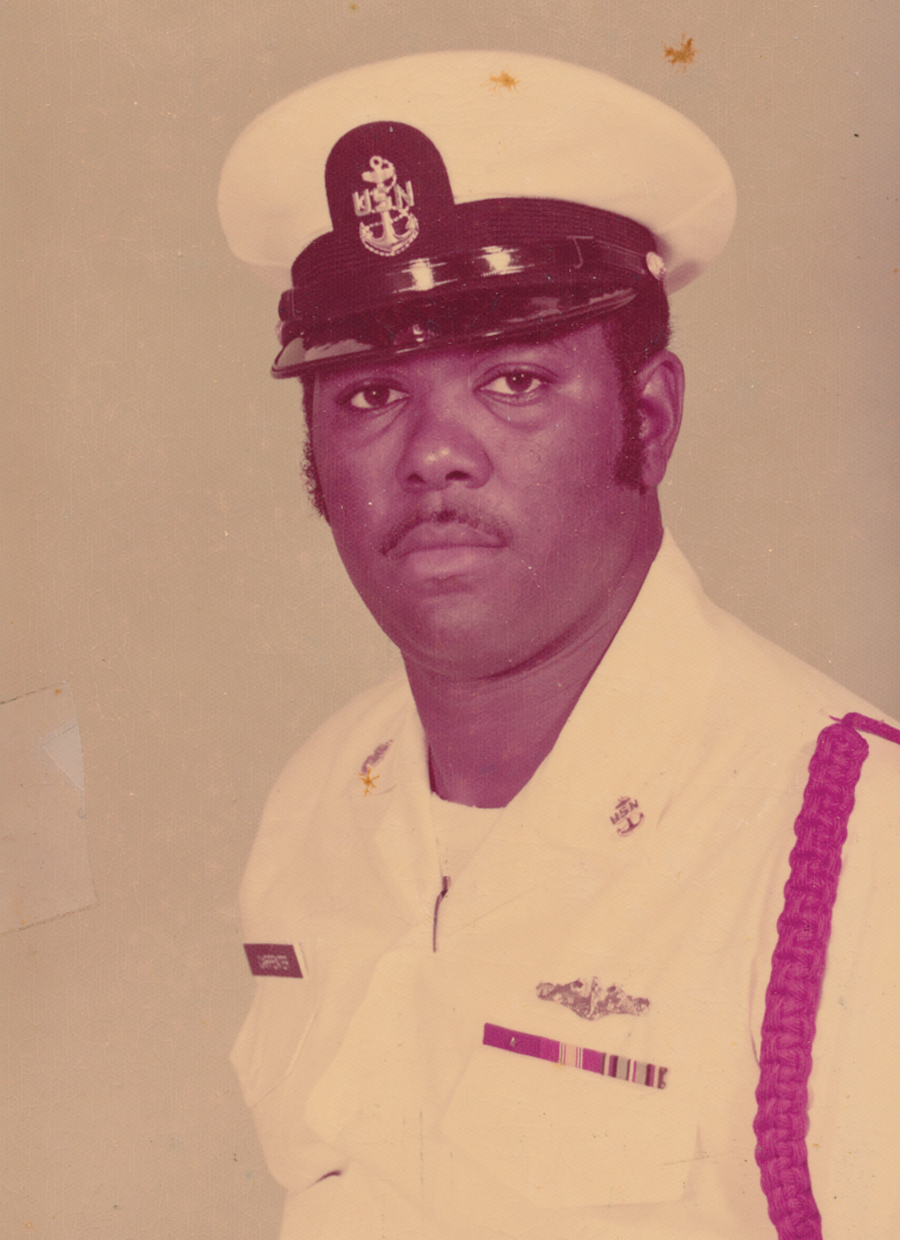

The chain store worker was 22-year-old Ciscero Carpenter Jr., employed as a cashier at Southern Pines’ A&P supermarket, a job he got because a manager had been impressed by Carpenter’s rapid advancement during his three-year hitch in the Navy. At first, some shunned the register manned by the young vet. As it turned out there was a limit to how often white customers were willing to pick the slow line. Speed and efficiency won out, and folks gravitated to his aisle.

Carpenter had spent a significant portion of his formative years at Weymouth House where both parents worked for James and Katharine Boyd. Ciscero Carpenter Sr. saw to the horses and tended the Moore County hounds while his wife cooked and did housework inside the home. Ciscero Jr. was actually born in the space that today serves as the Weymouth Center’s visiting writers’ quarters. As a favorite of Mrs. Boyd, the lad had the run of the place, even attending functions in the home as a guest, not as a servant. He palled around with the Boyds’ son, Jimmy, and the other neighborhood white kids.

The GNC members quickly established collegial relations with one another. Carpenter, now the group’s last surviving member, remembers that “we all became friends.” An executive committee was formed consisting of Lake, Peek, Moore and Gilmore. Seven working committees were established, “job opportunities” and “public accommodations” among them. Carpenter was selected to head the “education” committee. Dr. Lake later recalled that the members emphatically committed themselves to refraining from violence or political pressure. The GNC’s selected motto was “persuasion and not pressure.” However, Dr. Lake acknowledged that many of his fellow GNC members felt like “Daniel felt entering the lions’ den” given what promised to be an uphill battle persuading local businesses to change their ways. Even owners sympathetic to the aims of the GNC were expressing concern that integrating their establishments could result in an adverse impact to their bottom lines.

The GNC members fanned out across Southern Pines, urging its business owners to eliminate racial discrimination in their enterprises. Strong support from white and black pastors comprising the Southern Pines Ministerial Association, coupled with the leadership of the two church leaders heading up the GNC, bolstered the group’s moral authority. In late August of ’63, Dr. Lake reported to the Town Council that all of the industries in town were accepting job applications from African-Americans and pledged that candidates would be considered for employment without regard to race. The times, they were a-changin’.

Progress was also taking place on the public accommodations front, albeit at a less rapid pace. A majority of the restaurants, motels and other public facilities were now willing to serve the general public regardless of race. Gilmore, owner of the local Howard Johnson’s motel and restaurant, had led the way earlier by welcoming blacks at his HoJos in 1960. But holdouts still remained.

In October of ’63, Dr. Lake issued a statement in the newspaper stressing the underlying righteousness of the GNC’s cause, citing the biblical commandment that “Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.” He exhorted residents to “speak a good word to and for those stores, restaurants, hotels, motels, business houses, and industries who are now ready to employ and serve persons of both races.” The Pilot’s progressive editor Katharine Boyd offered unwavering support, observing in an editorial, “Negroes only want to be treated like everybody else.”

Despite Dr. Lake’s heartfelt appeal to their better angels, some business owners still resisted. Increasingly, the GNC turned to town councilman and former Civic Club President Felton Capel to assist it in finding a way forward. By then, the 38-year-old African-American resident of West Southern Pines and successful entrepreneur had gained the respect of nearly everyone in the community. In meetings at the Civic Club, Capel would counsel everyone to refrain from direct confrontation, and to continue following a policy of negotiation that often meant accepting piecemeal changes.

Capel described how this strategy worked in a 1987 interview. “I recall when we had a bowling alley in town and we would send them (blacks) in by couples. You know they had this thing about tokenism. They’d accept you if you didn’t send in but one or two or three.” Felton further reflected, “We’d get two white couples and two black couples and we went bowling. That’s how we started breaking that down.”

Gilmore and Capel often formed a tag team to break barriers. Once Gilmore called a public golf course that had excluded blacks and advised the pro that he desired a tee time for himself and Capel, “and that Felton was not going to be my caddie.” The two friends enjoyed their round.

Capel freely acknowledged that he leveraged his position as a councilman and Gilmore’s status in the community to wrangle entry where other blacks would have been barred. “It would be awkward (for recreational facilities owners) not to give the opportunity to play,” he would later say, “since I’ve got to sit up there (on Town Council) and appropriate monies and vote for them through travel promotions and get money to come in.” These groundbreaking entries provided significant inroads at a time when legal remedies for discriminatory practices simply didn’t exist. But the duo’s success did not always mean a permanent end to discrimination at an establishment. In 1962, Sunrise Theatre management permitted Gilmore and Capel to watch a movie together on the main floor despite the theater’s policy restricting blacks to seats in the balcony. But this proved to be a one-time exception, and segregated seating at the Sunrise continued thereafter unabated.

By March 1964, the GNC’s policy of friendly persuasion had resulted in remarkable and peaceful transformation. Dr. Lake reported that just two small restaurants still barred blacks altogether. Emulating the tactics of Capel and Gilmore, the GNC members volunteered to patronize the holdout restaurants for a week to demonstrate to the owners that the two races could dine together. One declined. The other agreed to the benefit of all — as Dr. Lake suggested.

Though blacks could now gain entry to nearly all Southern Pines’ service establishments, it did not sit well with the GNC that Charlotte’s Stewart & Everett Theatres, Inc., the owner of the Sunrise Theatre, still kept black and white customers apart once they purchased their tickets. Black patrons could only reach their assigned balcony area by ascending the exterior fire escape that now provides entry to a yoga studio. Stewart & Everett aggravated the situation by dividing the balcony with a partition so that white customers preferring to view a flick from a higher vantage point would do so without mingling with those of another race.

At the request of the Town Council, Stewart & Everett’s president, Charles Trexler, came to Southern Pines on April 23, 1964, for a meeting with the council and the GNC executive committee to address these grievances. New Mayor Norris Hodgkins Jr. mediated the discussions. At the session, Trexler announced three measures that Stewart & Everett would be taking: (1) the doors from the partition running down the middle of the balcony would be removed; (2) a concession stand would be installed in the balcony; and (3) the theater would integrate immediately if civil rights legislation was passed by Congress — or would resume negotiations with the Southern Pines GNC if it became apparent that such legislation would not pass. It was then uncertain whether President Lyndon B. Johnson’s pending civil rights legislation would be enacted. The bill was stalled in Congress due to intense filibustering by Southern senators, including Sam Ervin and B. Everett Jordan from North Carolina.

Trexler may have considered these steps meaningful, but the GNC attendees essentially viewed them as a dodge since the company was still unwilling to stop segregating theater patrons unless legally required to do so. The unappeased Dr. Lake and Rev. Peek informed Trexler and the Town Council that the Stewart & Everett proposal was unsatisfactory.

In its 10 months of existence, the GNC had refrained from conducting public protests and demonstrations since the group’s strategy of privately negotiating with the town’s business owners had paid dividends. This time, the GNC leadership concluded that the stiff-armed resistance by such a high profile business could not go unchallenged. Immediately after the meeting, the GNC began planning a demonstration at the Sunrise, scheduling it for April 26th prior to a 3 p.m. Sunday matinee showing of the forgettable Tony Randall vehicle, 7 Faces of Dr. Lao.

Working together, the GNC members developed a novel plan for the demonstration. A number of African-Americans, including several youngsters, would be chosen to stand in line at the Sunrise’s box office. Once at the head of the line, the would-be moviegoers would ask to be seated on the main floor. Expecting the request to be denied, the rejected individuals would cycle through the line repeatedly, each time renewing their seating requests. The demonstration didn’t involve any speeches or chants. The GNC calculated its low-key approach would make its case more effectively than any provocative strategy could.

The black members of the GNC set about rallying support from the various West Southern Pines churches and the Civic Club urging their members to be in attendance outside the theater once the line formed for the movie. Dr. Lake and the white contingent of the GNC were also on board. According to The Pilot, at the appointed hour the “Negro men and women, all well-dressed young people, lined up in front of the box office where Robert Dutton, local theater manager . . . refused to sell them tickets.” Three of the demonstrators contacted for this story believe a woman, and not Dutton, was working in the box office. In any event, each of the blacks in line — wearing a small, hand-printed card pinned to his or her clothing stating the reason for the demonstration — was turned away. As planned, this process would continually repeat itself. Rev. Peek and Capel did not stand in the line but kept an eye on things to make sure the demonstration proceeded without incident. Sgt. Charles Wilson provided a police presence across the street where 30 or so African-Americans and some whites looked on from the railroad platform.

White patrons lined up to see the movie, too, and most seemed unconcerned that they were caught in the middle of a civil rights demonstration. The Pilot noted that “(t)he addition of the white patrons, who all received tickets as they reached the box office, resulted in separation of the Negroes at some places along the line which at one time exceeded 100 feet or more.” The recurring discussions at the box office between the demonstrators and the ticket salesperson about why management would not admit the black patrons to the main floor slowed the movement of the line considerably, causing some impatience, even among the youngest of the demonstrators. Felton’s son Mitch Capel, then just 9 and now a professional storyteller appearing across the country as “Gran’daddy Junebug,” was cajoled into staying in the line by his mother’s promise of a treat from the bakery next door. Longtime West Southern Pines resident Clifton Bell, then a teenager, also recollects devouring tasty doughnuts from the bakery following his long stints in the line. Eventually, Dutton started a separate line so the white customers could proceed without further delay into the theater.

The account appearing in The Pilot said the demonstration was peaceful in all respects. But something happened to Ciscero Carpenter Jr. while waiting his place in line that, had he been less stoic, might have led to a more chaotic outcome. “I got shot with a pellet gun just above and between my eyes,” says the Navy veteran, showing the resulting bump on his forehead, still evident 54 years later. He was more stunned than hurt. “I saw the guy that did it. I remember Iris Moore (GNC member) comforted me. I did not react. Don’t know what would have happened if I had.”

According to The Pilot there came a time when Felton Capel pulled the youngest demonstrators (including Mitch) out of the line, perhaps feeling the need to protect the younger demonstrators after the incident with the pellet gun, though no one can say for sure. The demonstration continued for over half an hour with some of the participants cycling up to the box office as many as 10 times.

While Stewart & Everett still refused to change its policy, reaction to the conduct of the demonstration was generally favorable. Katharine Boyd’s editorial commended “the quality of the dignified demonstration conducted here

. . . Such a protest is deserving of as much or more response by theatre ownership as the response evoked by protests — some of which we are told, were not as orderly — at other theaters of the chain.”

Proponents of the Civil Rights Act finally broke through the Senate filibuster, and on July 2, Johnson signed the act into law. Shortly thereafter, Dutton admitted four young blacks into the Sunrise. They were allowed to patronize the concession stand and sit anywhere they liked, including the main floor. It was a watershed moment, and other breakthroughs followed. Later in the summer, the new West Southern Pines swimming pool was completed and opened to all races. At the dedication, Mayor Hodgkins paid tribute to the GNC and its unstinting efforts to foster good will and peaceful change.

There were still skirmishes to come. The consolidation and desegregation of the local schools brought new challenges that were not always dealt with smoothly. And equal opportunity of employment remained elusive for many, including Carpenter who, despite stellar qualifications, was continually stonewalled. Frustrated, he elected to re-enlist in the Navy in June of ’64 where he built on his admirable service record, even drafting a manual the Navy uses to this day. After retiring from the service in 1981, he returned to West Southern Pines, working long past normal retirement age.

Now, Carpenter prefers not to dwell on the discrimination he faced as a younger man. “It only made me stronger and work harder,” he says. But he is proud that Southern Pines was more “advanced” in addressing and remedying racial discrimination than some other parts of the state. And he takes special pride in the role he played.

Two leaders who played important roles in the civil rights movement in Southern Pines died recently: Felton Capel and Norris Hodgkins Jr. Peaceful change in a turbulent time is their legacy. But, one suspects, they would be the first to say, they didn’t march alone. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is Pinestraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.