An OK place to visit, but you wouldn’t want to live there

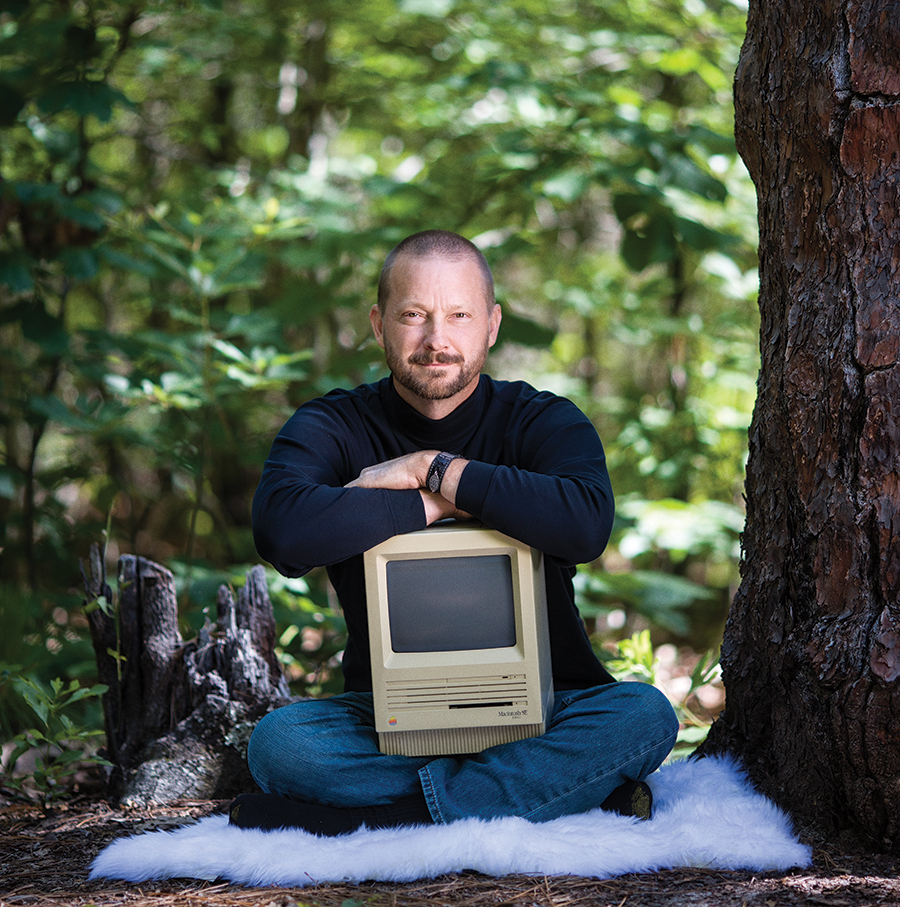

By Stephen E. Smith

In the mid-1980s, actor Robert Mitchum appeared on a late-night talk show to promote his latest film. The host asked if the movie was worth the price of admission and Mitchum replied: “If it’s a hot afternoon, the theater is air conditioned, and you’ve got nothing else to do, what the hell, buy a ticket.”

Readers should adopt a similar attitude toward Tom Clavin’s Dodge City: Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, and the Wickedest Town in the American West. If you’re not doing anything on one of these hot summer afternoons, what the heck, give it a read.

Dodge City is a 20-year history of the Kansas military post turned cow town that has come down in popular culture as the Sodom of the make-believe Wild West. No doubt Dodge had its share of infamous gunfighters, brothels and saloons, including the Long Branch Saloon of Gunsmoke fame, and there were myriad minor dustups, but nix the Hollywood hyperbole, and Dodge City’s official history is straightforward: Following the Civil War, the Great Western Cattle Trail branched off from the Chisholm Trail and ran smack into Dodge, creating a transitory economic boom. The town grew rapidly in 1883 and 1884 and was a convergence for buffalo hunters and cowboys, and a distribution center for buffalo hides and cattle. But the buffalo were soon gone, and Dodge City had a competitor in the cattle business, the border town of Caldwell. Later cattle drives converged on the railheads at Abilene and Wichita, and by 1890, the cattle business had moved on, and Dodge City’s glory days were over.

Clavin focuses on the city’s rough-and-tumble years from 1870 through the 1880s, explicating pivotal events through the lives and times of the usual suspects — Bat Masterson, the Earp brothers, Doc Holliday et al. He fleshes out his narrative by including notorious personages not directly linked to Dodge City — Billy the Kid, John Wesley Hardin, Wild Bill Hickok, “Big Nose” Kate, Buffalo Bill Cody, Sitting Bull, the Younger brothers, and a slew of lesser characters such as “Dirty Sock” Jack, “Cold Chuck” Johnny and “Dynamite” Sam, all of whom cross paths much in the manner characters interact in Doctorow’s Ragtime. Also included are abbreviated histories of Tombstone — will we ever lose our fascination with the 30-second shootout at the O.K. Corral? — and Deadwood.

If all of this sounds annoyingly familiar, it is. There’s no telling how many Wild West biographies, histories, novels, feature films, TV series, documentaries, etc., have been cranked out in the last 140 years, transforming us all into cowboy junkies. Our brief Western epoch has so permeated world ethea that blue jean-clad dudes in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, might be heard to say, “I’m getting the hell out of Dodge,” in Uzbek, of course.

Clavin offers what amounts to a caveat in his Author’s Note: “. . . Dodge City is an attempt to spin a yarn as entertaining as tales that have been told before but one that is based on the most reliable research. I attempted to follow the example of the Western Writers of America, whose members over the years have found the unique formula of combining strong scholarship with entertaining writing.”

So what we have is a hybrid, a quasi-history not quite up to the standards of popular history, integrated into a series of underdeveloped episodic adventure tales that ultimately fail to entertain. If Doris Kearns Goodwin and David McCullough are your historians of choice, you’ll find that Dodge City falls with a predictable thud. It’s simply more of the same Western hokum. The writing isn’t exceptional, the research is perfunctory, most of the pivotal events are common knowledge, and the characters are so familiar as to breed contempt.

If you have a liking for yarns by writers such as Louis L’Amour, Luke Short and Larry McMurtry, Dodge City isn’t going to make your list of favorite Westerns. Without embellishment, the narrative loses its oomph, and the episodic structure diminishes any possibility of a thematic continuity, which is, of course, that the lawlessness that marked Dodge City’s formative years is a metaphor for the country as a whole, that violence and corruption are a fundamental component of American life.

On a positive note, readers of every persuasion will likely find the book’s final chapter intriguing. Clavin follows his principal characters to the grave. Wyatt, the last surviving Earp brother, ended his days in Los Angeles at the age of 80. Doc Holliday died in Colorado of tuberculosis at 36, his boots off. “Big Nose” Kate, Doc’s paramour, lived until 1940 at the Arizona Pioneers’ Home, dying at the age of 89.

Of particular interest is Bartholomew William Barclay “Bat” Masterson, Wyatt Earp’s dapper buddy in the “lawing” business. Whereas Earp’s claim to fame ended with his exploits as a Western peace officer and cow town ruffian, Masterson went on to a life of greater achievement. He became an authority on prizefighting and was in attendance at almost every important match fought during his later years. He was friends with John L. Sullivan, Jack Johnson and Jack Dempsey. In 1902, he moved to New York City and worked as a columnist for the New York Morning Telegraph. His columns covered boxing and other sporting events, and he produced op-ed pieces on crime, war, politics, and often wrote of his personal life. He became a close friend of President Theodore Roosevelt and remained a celebrity until his death in 1921.

It promises to be a long, hot, unsettling summer. If you’ve got nothing better to do, turn off cable news, slap down $29.99 and give Dodge City a read. It’s little enough to pay for a few hours of blessed escapism. PS

Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of seven books of poetry and prose. He’s the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press awards.