Sandhills’ Renaissance man Rassie Wicker

By Bill Case

It was accepted as Gospel in Pinehurst that Rassie Wicker’s ability to perceive, study and comprehend the world around him bordered on the supernatural. Hardly any subject escaped his quest for knowledge. He seemed to understand everything and could fix anything.

That was until July 22, 1944, when the War Department message dreaded by every serviceman’s family arrived. The telegram said that Lt. Jim Wicker, Rassie’s 23-year-old son, had been missing in action since July 7, barely a month after the Allies landed on the beaches of Normandy. A veteran of 27 bombing missions over Germany, Jim had been lost over Holland when the B-17 Flying Fortress he co-piloted collided in mid-air with another B-17. Most of the 10-man crew had perished. Jim and two enlisted men were unaccounted for.

Home on leave seven months earlier, Jim married Nancy Richardson, his high school sweetheart and the daughter of Pinehurst’s postmaster. It was the young bride who shared the news of the War Department’s wire with Rassie, his wife, Dolly, and Jim’s sister Eloise, casting the twin clouds of fear and uncertainty over the entire family.

Rassie was no stranger to the horrors of war, having soldiered on the front lines in the Meuse Argonne Offensive, the largest and bloodiest operation of World War I that cost over 26,000 American lives. When Jim revealed his intention to sign up for cadet training as an Army Air Corps pilot in 1942 — unbeknownst to his family he had already taken flying lessons — Rassie cautioned him that wartime service was “ugly, spirit-breaking labor, done under strict orders and under the most heartbreaking conditions.” If he was determined to serve, Rassie urged him to seek placement in a photographic post. After all, Jim had already been trained as a civil cartographer. Rassie admonished his son, “I thought I made it plain enough that I was not agreeable to your going into the air force as a pilot, bombardier, or navigator of combat ships.”

Rassie practically begged his son to reconsider. “The thought of your having to go through what I know would be ahead of you would be enough to unbalance what little reason of which I am possessed, and I don’t know what it would do for your mother,” he wrote. “The loss of you to us would mean the wreck of us both.” The son disregarded the father’s advice and reported to Nashville for officer’s flight training.

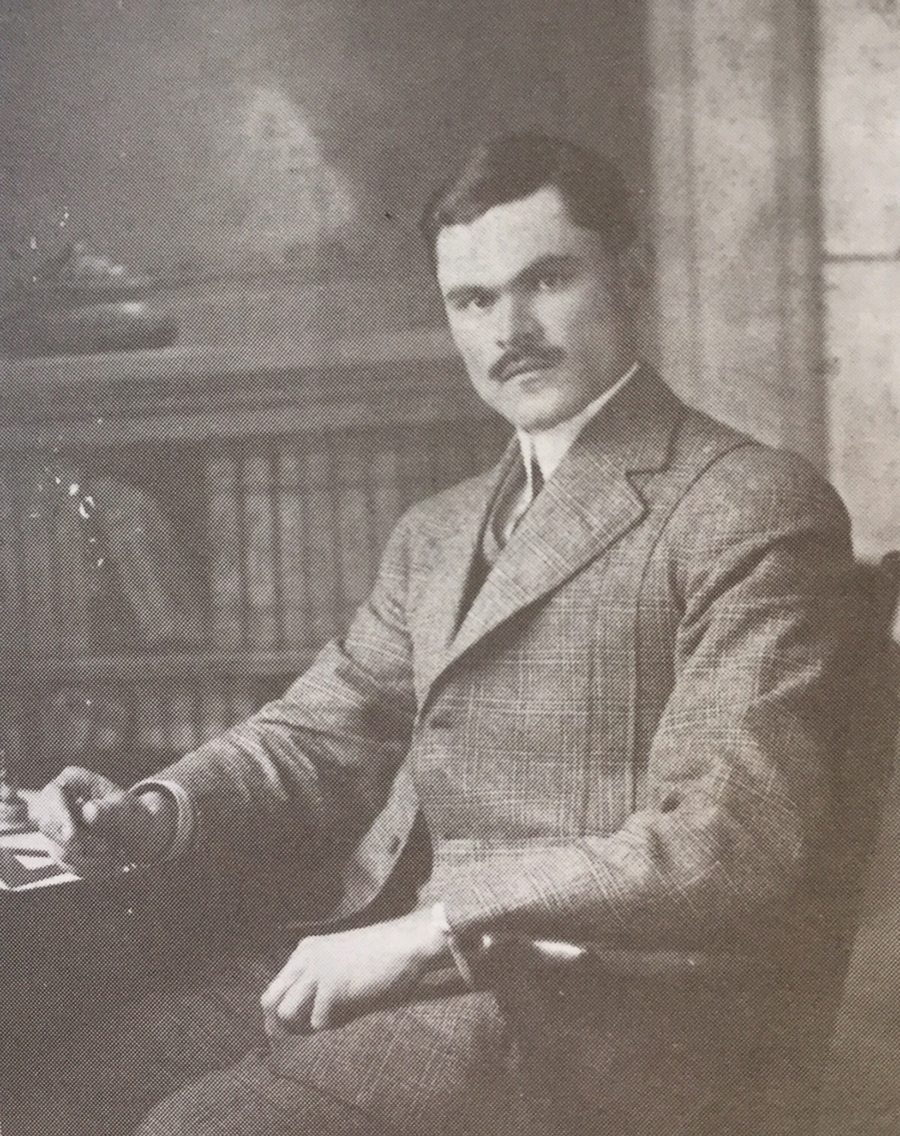

Now, with Jim missing, Rassie faced the potential — even probable — loss of his son. What possible comfort could there be in having been prescient? If anything, it made his grief all the more palpable. Rassie had gained a reputation in Pinehurst as a man of exceptional capability who adroitly performed any task he set out to do, regardless of its complexity. While his primary occupation was that of a surveyor and civil engineer, the 52-year-old Wicker’s versatility was such that those who knew him, if asked to name the skill at which he most excelled, could easily have given any of a dozen responses. Instead, he sat helpless.

Born in 1892 to James Wicker and Lucretia Mills, Rassie attended a one-room schoolhouse in his birthplace in nearby Cameron. It does not appear that he received any formal schooling in Pinehurst after James moved the family there in 1902. But, like Abraham Lincoln, Rassie read everything he could get his hands on, up to and including the Sears & Roebuck catalog.

Rassie’s father found that his cabinetmaking skills were in high demand in the 7-year-old community. Setting up shop near where the Manor Inn is now located, James received the bulk of his woodworking projects from Leonard Tufts, who assumed control of the family’s privately owned resort and town in the wake of James Tufts’ death, also in 1902. The young Rassie found work in the company town, too, starting as a delivery boy in the pharmacy. An enterprising teenager who nonetheless had time for a bit of fun (lanky and raw-boned, he participated in a farcical local baseball game in a red and green suit), Rassie quickly came into contact with the print shop employees who worked in the same building as the pharmacy. Soon, he had two jobs. Given the daily menu alterations at the Carolina Hotel, there was an unending flow of printing work, and it was not long before he mastered that trade.

The young man’s aptitude for catching on quickly wasn’t lost on Tufts, who used Rassie in a wide variety of roles. He assisted Pinehurst’s electrician, Owen Farrey, and lineman, Seward McCall, in cutting down the trolley line after Leonard decided to discontinue the service. When the installer of the first elevator in the Carolina Hotel walked off the job in a huff, leaving the elevator stranded at the top floor, it was Rassie who got the call. Despite knowing next to nothing about the equipment, he managed to bring the lift to the ground and, with typical dispatch, returned it to working order. Under the tutelage of civil engineer Francis Deaton, he helped survey the properties Leonard was buying, selling or developing. Rassie relished solving the kind of mathematical problems where there was only one right answer, and surveying required the same sort of exactitude. In an effort to enhance his knowledge, the largely self-educated Rassie passed the entrance exam into North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts (now North Carolina State University).

After completing the 1911-12 academic year in Raleigh, he was back working in Pinehurst, spending an ever-increasing percentage of his time in surveying. Though he never completed his studies, Rassie was permitted to hang out a shingle as a registered civil engineer since his work in the field predated the state’s establishment of educational requirements. In 1912, someone convinced him to run for Moore County surveyor and he cruised to victory. There was only one problem: At the swearing in, Rassie learned he was one year shy of meeting the position’s minimum age requirement of 21. Accordingly, he stepped down.

Rassie’s surveying work required him to spend considerable time out of doors in the forests and fields of Moore County, and he reveled in the observation of nature. With three friends, he organized a five-day paddle down the Little River from Vass to Fayetteville, constructing two homemade boats for the voyage. Upon arriving at the party’s destination, Rassie reported to the Pinehurst Outlook that “we tied up to wharves of that old town; changed our river clothes for railroad style, bode our (homemade) boats farewell, and bought tickets to Aberdeen.”

By 1917, Rassie was already considered a person of prominence in Pinehurst. The Outlook listed him among those who “built the community.” He married his sweetheart, a 21-year-old Cameron native, Mary “Dolly” Loving and, like his son after him, left almost immediately for military service overseas. He survived the Western Front physically unscathed and returned to Pinehurst in 1919. Jim was born in 1920, and Eloise came in 1922. In 1923, the burgeoning family moved into the house that Rassie built at 275 Dundee Road in Pinehurst.

In addition to surveying, Wicker ran the movie projector at the new Carolina Theatre in Pinehurst. He supervised a five-man crew building houses for Leonard Tufts, an assignment he was unable to perform as expeditiously as Leonard would have liked. Despite Rassie’s crew completing construction of 10 homes inside of 11 months, Leonard expressed his dissatisfaction. “(Y)ou should have completed 47 houses,” complained the tough taskmaster. The beleaguered Rassie informed his boss he was incapable of meeting such an unrealistic target, and he voluntarily excused himself from further homebuilding. Leonard appears not to have taken the resignation personally, since he continued to inundate Wicker with other assignments.

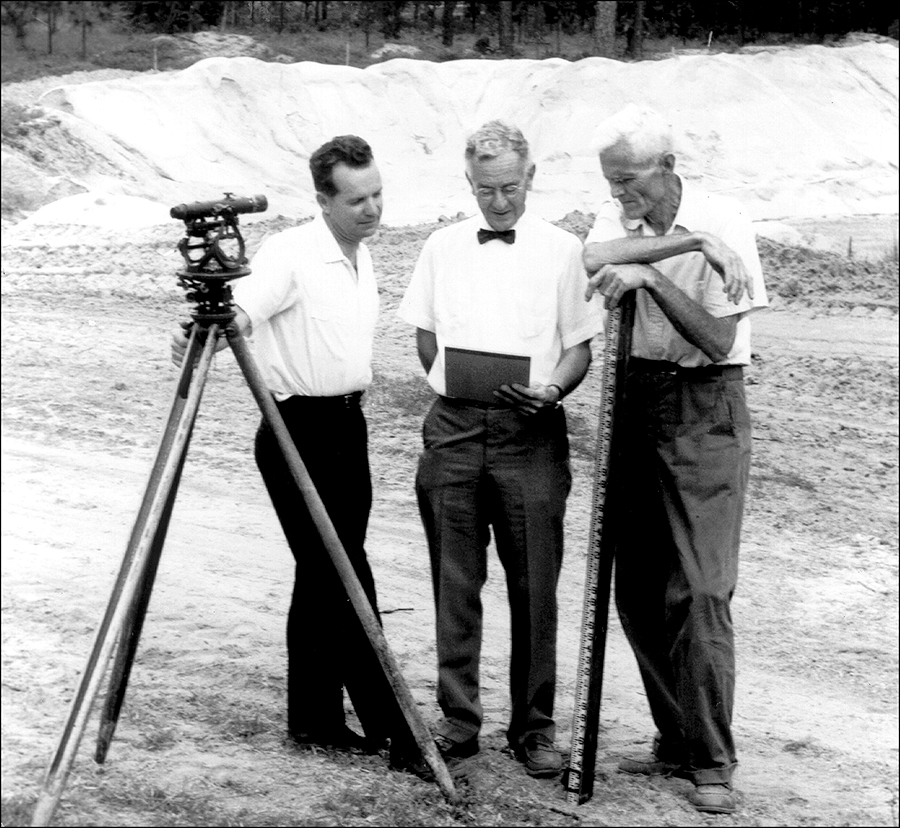

One task involved preparing a detailed map of the entire Sandhills area — a job Rassie, Francis Deaton and James Swett undertook in 1921. Much of the area was still unsettled dense pine forest. Land elevations and precise paths of Moore County’s watercourses were unknown. The laborious and meticulous work took nearly a decade to complete. One result of this effort was the decision to focus on development in the triangle between Pinehurst, Southern Pines and Knollwood. The Pilot reported in November 1931: “Rassie Wicker has been in the field on the proposed extension of Pennsylvania Avenue from the top of the hill in ‘Jimtown’ (Western Southern Pines) to the boundary of Pinehurst.”

While mapping unidentified creeks, Wicker took it upon himself to name them. According to Tony McKenzie’s “Tribute to Rassie Wicker,” Rassie called one offshoot of a creek “Joe’s Fork” in honor of a Jamaican, Joe Melton, who “drove an oxcart from hotel to hotel collecting food scraps and taking them to the Pinehurst piggery.” Republican political operatives once again began floating Rassie’s name as a candidate for county surveyor. He wryly shot down that trial balloon with a Will Rogers’ style quip. The Pilot reported that Wicker “denies the allegation and spurns the allegator.” Rassie went on to say, “ I always was, is, and always will be a Democrat.”

Rassie’s work in Pinehurst brought him into contact with the landscape architect Warren Manning, a protégé of the man who designed New York City’s Central Park, Fredrick Law Olmsted. As the Tufts’ architect-in-charge, Manning had the final say regarding nearly all plantings in the village. A sponge for absorbing the insights of experts, Rassie’s acquaintance with Manning enabled the younger man to learn how the interrelation of selected plantings could enhance a home or streetscape. Rassie opened his own business, Pinehurst Landscape Service, by the mid-1920s to capitalize on the numerous opportunities for a landscaping enterprise in a village less than 20 years old built on pine barrens.

By the end of the Roaring 20s, Leonard Tufts’ son Richard began to supplant his oft-ailing father in running Pinehurst’s affairs. The father and son, however, shared their appreciation of Rassie Wicker. In a personal letter, Richard raved, “You are getting a reputation with us as an architect, landscape designer, and the sort of handyman to refer things to when we want something that looks extra nice.”

Rassie was given the responsibility for locating and laying out new streets along with the water and sewer lines. According to Tony McKenzie, Wicker “took the liberty of giving all the newest streets names. He chose to use the last names of the people who provided manual labor to build Pinehurst.” They included Graham, Short and Caddell. He supervised construction of the Given Library and the hangar for the Moore County Airport. Leonard entrusted Rassie with the preparing and placing of historic markers identifying the ancient Yadkin Trail, four of which still remain.

Everything Rassie encountered seemed to pique his curiosity. Though often racked with migraine headaches, he invariably finished three books in a three-day period — the allowable bookmobile lending policy at the time — then scoured National Geographic and the Encyclopedia Britannica, front-to-back and A-to-Z. Surveying and mapmaking led him to an interest in the historic derivations of land titles in Moore County. His research dated back to the initial grants of the king of England. The completion of that project spun off into a deeper history of the county and ultimately the state. He became an organizing member of the North Carolina Society of Historians and a valued contributor to the Moore County Historical Association. He wrote numerous columns he titled “Historical Sketches” in The Pilot. One of his writings described his successful search for the North Carolina homes of Scottish heroine and Revolutionary War figure Flora MacDonald. His research culminated in the publication of a book that continues to be a leading reference for county historians, Miscellaneous Ancient Records of Moore County, compiling a massive amount of 18th century data.

His landscaping work led to the study of the local flora and fauna. After locating a sweetgum tree in Pinehurst, he took the time to compare its characteristics with other known varieties of the species. It turned out there existed no other known sweetgum tree with similarly shaped lobes on its leaves. The uniqueness of the discovery was subsequently confirmed by a nationally known expert at Harvard University.

As if those pursuits weren’t enough, he had hobbies, too, including playing the piano, making his own dulcimer, singing in a chorus, acting in the occasional theater production, beekeeping and orchid growing. Perhaps Rassie’s most unique interest was sparked after he found a nest of orphaned quail in his yard and adopted them as pets. His care and feeding of the birds ultimately led to their taming. He cultivated wild plants he thought might improve their diet. His domesticated “Peewee” even fluttered its way into feature stories in The Pilot and Pinehurst Outlook.

His never-ending pursuit of learning took him beyond this world to a study of the heavens. He became an astronomer. Wanting a telescope to gaze more closely at the stars, Rassie fabricated one himself. In 1935, he contributed periodic columns to the paper with the purpose of educating its readers on locating the planets — “The Heavens in October,” etc.

Wicker was an inveterate writer of letters to local newspapers. Rather than pontificate he would raise issues overlooked by everyone else. And, though usually soft-spoken, he could launch into vituperative commentary when circumstances warranted. Concerned that a proposed constitutional amendment would transfer power from the “common people” to the state legislature, he colorfully opined that “(i)f it does, then it should be hung higher than Haman, drawn and quartered, boiled in oil, beheaded, disemboweled and buried in the deepest sea, and its tomb forgotten.” As part of the war effort, in 1944 Wicker was working as an engineer in Sanford for General Machinery and Foundry when he learned that his son, Jim, was missing in action.

The Wicker family tried to stay strong, but that was next to impossible. Jim’s wife, Nancy, wrote daily letters to her husband, holding them in safekeeping that he might one day have an opportunity to read them. Earl Monroe, Rassie’s best friend, noted that the interminable waiting for news about Jim drove Rassie, “a little crazy.” Finally on September 23rd, a telegram arrived confirming that Jim, after safely parachuting to the ground, had been captured by the Germans and was being held as a prisoner of war. The Wicker family was overjoyed. The only other survivor of the midair collision from his B-17 was the waist gunner, Clyde Matlock.

Jim was held in captivity at Stalag Luft I until May 1, 1945, when the camp’s guards fled as the Russian Army approached from the east. The Russians liberated the prisoners at 10 a.m. Two weeks later, Jim arrived at Camp Lucky Strike in France to await transport home. He soothed his anxious family, telling them, “All of you stop worrying now. I’m practically in the front yard.” And fittingly, it was Independence Day when he finally arrived home. Jim later received numerous commendations for his heroic service, including the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Rassie returned to his usual activities in Pinehurst, but managed to spend increasing amounts of time with Earl Monroe, his son Bud, now 80, and Tony McKenzie at the blacksmith shop at the corner of Rattlesnake and McCaskill roads. Bud recalls that Rassie loved working there as well as in his small workshop at home. Rassie welded and woodworked, like his father had. He gave away everything he made to his friends and children, including intricately crafted grandfather and grandmother clocks.

Bud Monroe proudly shows off several of Wicker’s handmade wooden pieces at his Murdocksville Road home. “How on earth are you going to go about describing what an incredible wizard Rassie Wicker was?” asks Monroe.

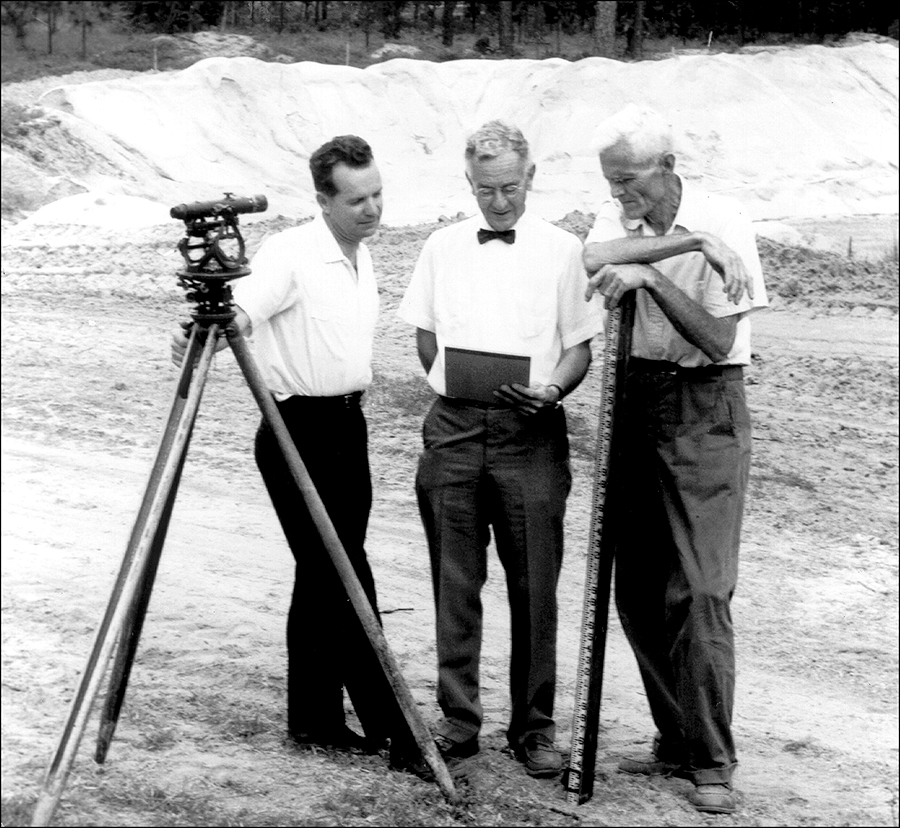

Wicker kept surveying until very late in life. A familiar and welcoming site in Pinehurst was Rassie driving his old Chevy down Cherokee Road with his surveyor’s rod protruding out the back window. As he aged, the white-haired Rassie began “taking on something of the majesty of an Old Testament prophet.” His community sought ways to honor him. In December 1971, he was the recipient of the Sandhills Kiwanis club’s Builders Cup for “the year’s most outstanding contribution to the county, made without thought of personal gain.” He passed away the following October at age 80. Dolly would die 16 years later.

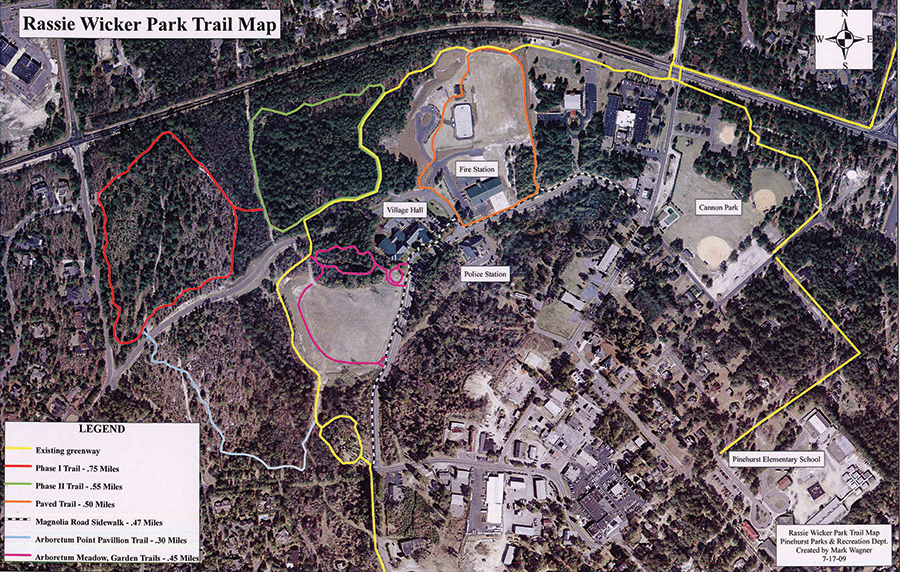

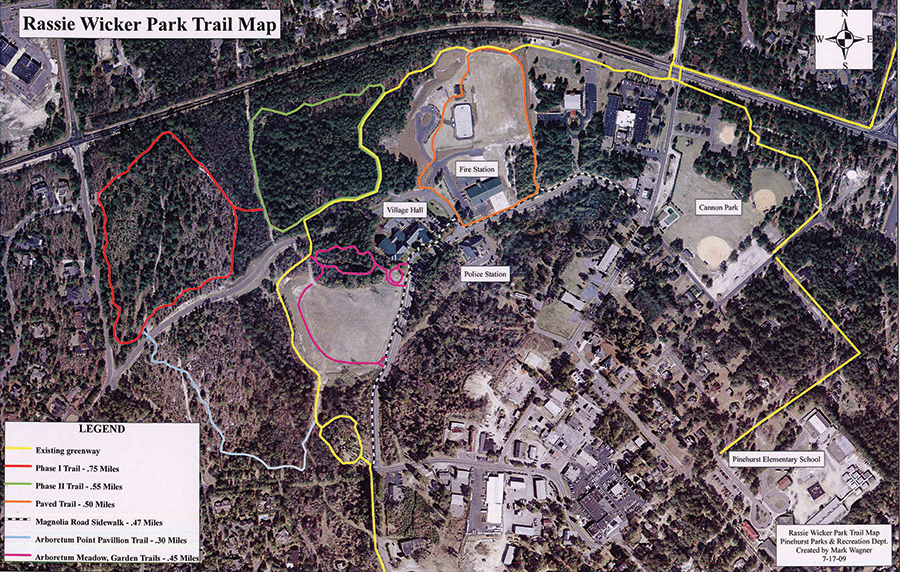

Recognition continued to come to Rassie posthumously. On Sept. 18, 1995 Pinehurst’s Village Council held a ceremony at the World Golf Hall of Fame to celebrate the naming of its newly acquired 100-acre recreational site, Rassie Wicker Park.

Jim Wicker piloted airplanes in the military for 21 years, and continued in aeronautic related activities thereafter. He and Nancy had two children, Jim, Jr., and Jill Wicker Gooding, both of whom maintain homes in Pinehurst. Rassie and Dolly’s daughter, Eloise, emulated her father’s penchant for scientific inquiry. She graduated from the University of North Carolina with a degree in botany and became Chapel Hill’s curator for its herbarium, part of the North Carolina Botanical Garden.

In a heartfelt message to Eloise who had just graduated from college, Rassie Wicker wrote, “I (and you too) know the pleasure — the deep and soul-satisfying pleasure — of having knowledge as one of your possessions. Not a knowledge confined to one subject, but a broad intellectualism which gives you a deep appreciation, not only of the distant and unapproachable things, but also of the little, homey, everyday creatures and incidents of which everyone’s life is made up … a bug or a worm or a plant each going about [its] appointed task, not haphazardly but in conformity with some great plan. These things come to me occasionally with overpowering force, but I have learned to keep them to myself except to a certain very few people who have seen this picture.”

Rassie Wicker did his best to see the whole picture. His passion flowed from a strongly held belief that the more he studied the world, the more he would be able to discern recurring patterns, to see how everything in it — the beauties and the mysteries — fit together. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.