Century-old apartment house gets a new lease on life

By Deborah Salomon • Photographs by John Gessner

Soft green, rose and plaid upholstery. A what-not shelf filled with elephant miniatures. Floral duvet, matching bedside table skirt and drapes. Dark woods and polished silver. A baby grand in the parlor. Bedrooms sized like bedrooms, not basketball courts. Antiques with family connections.

Genteel, pretty, Southern.

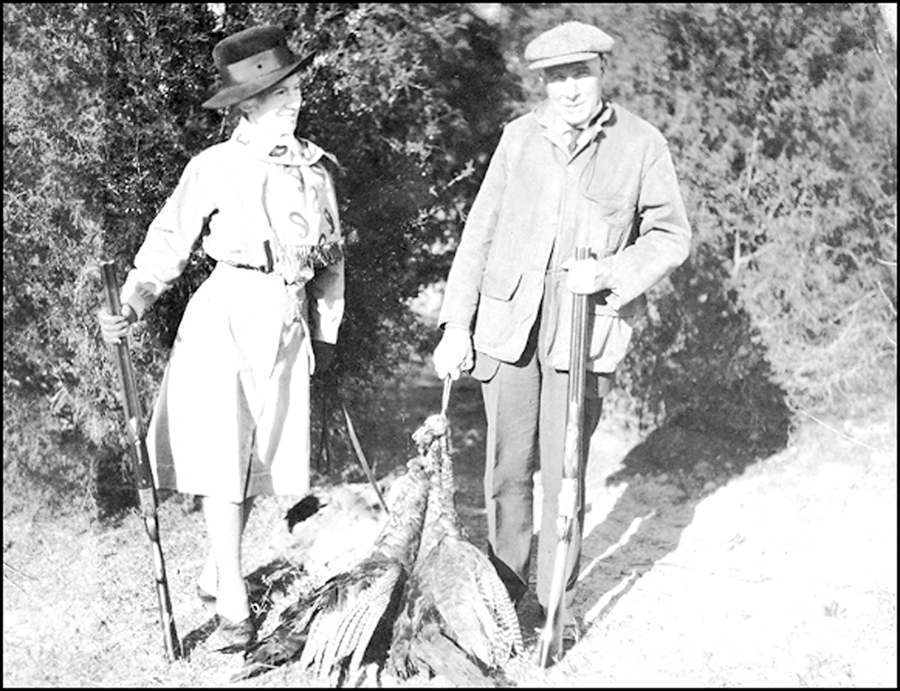

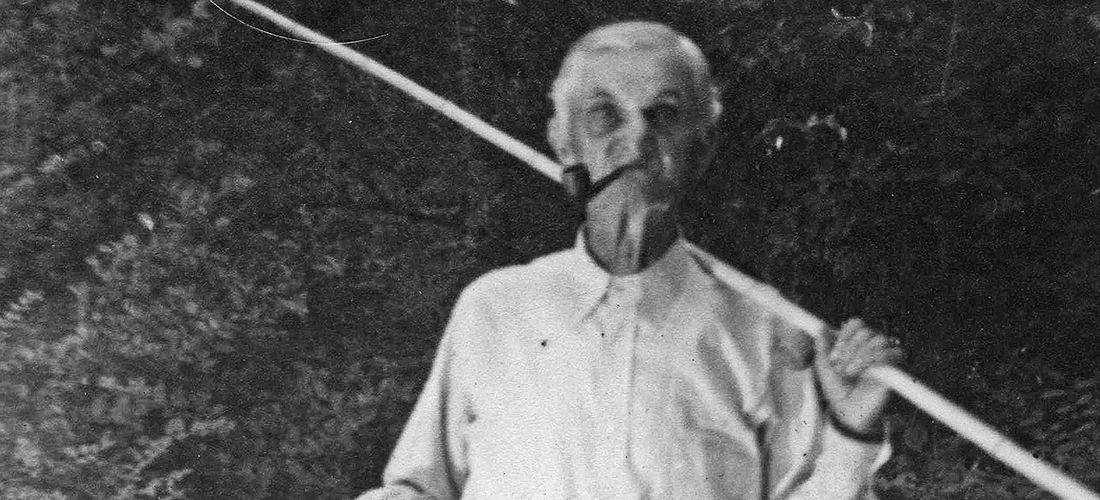

So goes Thistle Cottage, built on the edge of Pinehurst village by the Tufts family in 1916 as four apartments with separate entrances and separate furnaces to accommodate senior resort staff. Legendary Carolina Hotel doorman Sam Lacks and headwaiter George Ashe lived there. Subsequently, Annie Oakley and her husband, Henry Butler, occupied a first-floor apartment while she entertained guests during the winter season.

The apartment idea caught on. In 1918 the Pinehurst Outlook reported “the number of applications has surpassed expectations.” The building was renovated and minimally landscaped in 1922. Apartments got not only fresh paint but “modern” furniture, justifying $750 rent from October to May. Henry Page Sr. lived there in 1932, Roy Kelly from 1938 to 1962. In the 1980s Page and Hayley Dettor reconfigured the house as a longitudinal 3,200-square-foot two-story single-family dwelling with an unusual (for the Sandhills) full finished basement.

Yet something was missing.

No longer. In Jane and Jim Lewis’ 20-year tenure, scruffy grounds have become magnolia bowers with a carpet of English ivy.

“We didn’t want any newfangled vegetation,” Jane says.

Now three mini-porches and a secret garden exude a rocking-chair charm never out of style. Just inside the front door a 1990 version of a glamour kitchen suits the classic American cuisine Jim prefers when they eat in, which is most of the time.

“Meatloaf,” he nods. “I don’t go for fancy seasonings.”

Instead, Jim (from a South Carolina tobacco town) and Jane (family roots deep in antebellum Virginia) relish surrounding themselves with history.

“You can tell a lot about a man by looking at his books,” Jim believes. An entire wall of bookshelves in the TV room reveals his love of baseball and American history, while Jane falls into the gardening/interior design category, having worked with the fabric company Brunschwig & Fils Inc., whose installations at the White House and Palace of Versailles join the dining room, living room and bedrooms of Thistle Cottage — its name, bestowed by the Tuftses, emblematic of Scotland.

“I’m sentimental,” Jane says. “I like to mix in old family books . . . look inside them and see which great-great (relative) it was given to.”

How Jane and Jim Lewis found Thistle Cottage begs the beginning “. . . once upon a time.”

They both have fond memories of Southern living. Jim moved around a lot — 14 times since his marriage alone. Jane, from a Navy family, lived mostly in Charlotte, with her grandmother and “old maid aunts who didn’t have any other place to go.” He graduated from Davidson, she from Queens College. As a communications executive at Southern Bell, then Lucent Technologies, Jim was sent to Savannah and Richmond, which they loved, finally Denver. As Jim neared retirement, he requested relocation to Charlotte, now a big, busy city — less than ideal for retirement, they discovered. Pinehurst was a frequent golf destination. “I tried to persuade Jane that this was the place (to live),” Jim says. They struck a deal. “We’ll practice living here for a year and if Jane doesn’t like it, we’ll go back to the empty-nester in Charlotte.” To this end, Jim looked around and found Thistle. “I liked it the minute I walked in . . . the open space (kitchen, breakfast room, family-TV room). I called Jane to come down and take a look.”

They bought Thistle in 1997 as a weekend retreat. “We subscribed to the newspaper, pretended we lived here,” Jim recalls. By 1999 the transition was complete. They sold the empty nest and took up permanent residence in a house with plenty of history for Jim to explore, plenty of land for Jane to garden and plenty of room for their sons and, later, grandchildren, to spread out.

At first glance, except for the grounds, Thistle looked “finished” to Jim. He admired the thriftiness of a previous owner, who took down paneled doors and laid them horizontally as wainscoting. Still, they found plenty to do. Removing a wall between smallish dining and living rooms made both appear larger. They created an upstairs spa bathroom and dressing room with washer-dryer, installed crown moldings, replaced crumbling exterior wooden shutters with hard-to-find replicas, lighted and brightened everything.

“I like happy colors,” Jane declares. No contemporary grays and neutrals. From three previous houses she brought forward the same stunning crimson wallpaper in the dining and living rooms. The kitchen and family rooms are a pale yellow. Oriental rugs feature primary rather than shaded colors. The master bedroom is done in red toile and the living room, a masterful mix of Brunschwig & Fils fabrics in bold hues — mostly florals, one geometric. Jim’s study is painted a forest green, to match his favorite sweater.

Jane’s antiques — tables, rush-bottomed chairs, sideboards, case pieces — are crowned by a grandfather clock crafted in the early 1800s by John Weidemeyer of Fredericksburg, Va. This “case” clock, long in Jane’s family, has a false front where coin silver spoons were hidden from Union Gen. Philip Sheridan, who charged down the Shenandoah Valley in 1864. Jane owns several of the spoons. Her collection of China export porcelain plates in the butterfly pattern hang on dining room walls.

She is especially fond of etchings by Hungarian artist Luigi Kasimir, picturing European churches, which she found bargain-priced in a second-hand shop. They set a classic tone in the foyer and upstairs hallway. Portraits of Gen. Robert E. Lee and Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson hang over a bedroom mantel, stripped to its original pine.

A painting of the Pine Crest Inn by local artist Jessie Mackay underlines Jim’s opinion that this landmark, although not luxurious, is as steeped in tradition as Pinehurst No. 2. “Everybody who’s anybody in the game of golf has been there.”

But the conversation starter in Jane and Jim’s Thistle has to be a bar nook built by a previous owner, with shelves displaying 280 mini liquor bottles, no duplications, the kind available on planes and trains in the good old days. They belonged to an aunt who began collecting them in the 1930s. Many, although unopened, are empty, the contents evaporated through the seal. Jim put up the narrow shelf and cataloged the bottles. Dusting them is a delicate chore, performed by Jane.

Historian Jim enjoys the Annie Oakley connection. Photos, memorabilia, even a gun of the era (“It came with the house”) form a small shrine in the family room. He’s ready with lore and dates, books and posters — proud of living where she did even if the walls are now crimson.

Jim and Jane Lewis have succeeded in providing Thistle Cottage an atmosphere both elegant and comfy, respectful of an era in the South — the ’50s and ’60s — which has yet to gain status with millennials busy simplifying and modernizing. An era when elders still recounted the history of their possessions.

“I love the lived-in feeling,” Jim says.

“Oh yes, we’ve been happy here,” Jane adds.

The upscaling of Thistle Cottage, particularly the landscaping, helped this outlying street where modest houses are being rejuvenated or replaced for a new generation of residents. “Now we have mothers with jogging strollers come by,” Jane notices. “It’s a real pleasure.” PS