Sixty years ago a wildfire ravaged the Sandhills

By Bill Case

The day dawned brilliant and balmy at Tom and Nancy Howe’s Aurora Hills farm in Pinebluff, North Carolina. It was a gorgeous spring morning on Thursday, April 4, 1963, except for the gusty winds that would blow throughout day. Tom finished breakfast with Nancy and the couple’s two young boys, Tommy Jr. and John, climbed into his pickup truck and drove to Pinehurst, where he worked at Clarendon Gardens, owned and operated by his father, Frank Howe.

Today, Clarendon Gardens is an upscale neighborhood off Linden Road, but in 1963, it was a magnificent, nationally acclaimed 160-acre botanical garden, attracting thousands of tourists who marveled at Frank Howe’s vast array of azaleas, rhododendrons and hollies. Springtime was Clarendon Gardens’ high season, and Tom Howe anticipated a busy day. The 25-year-old could never have foreseen the harrowing, grueling hours he and other Moore County residents were about to endure.

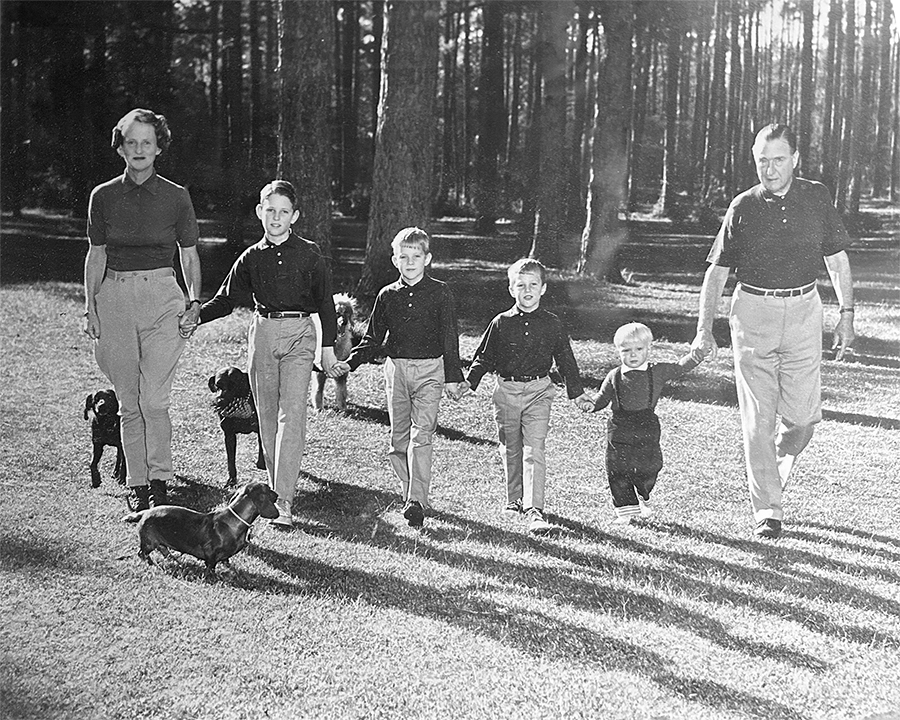

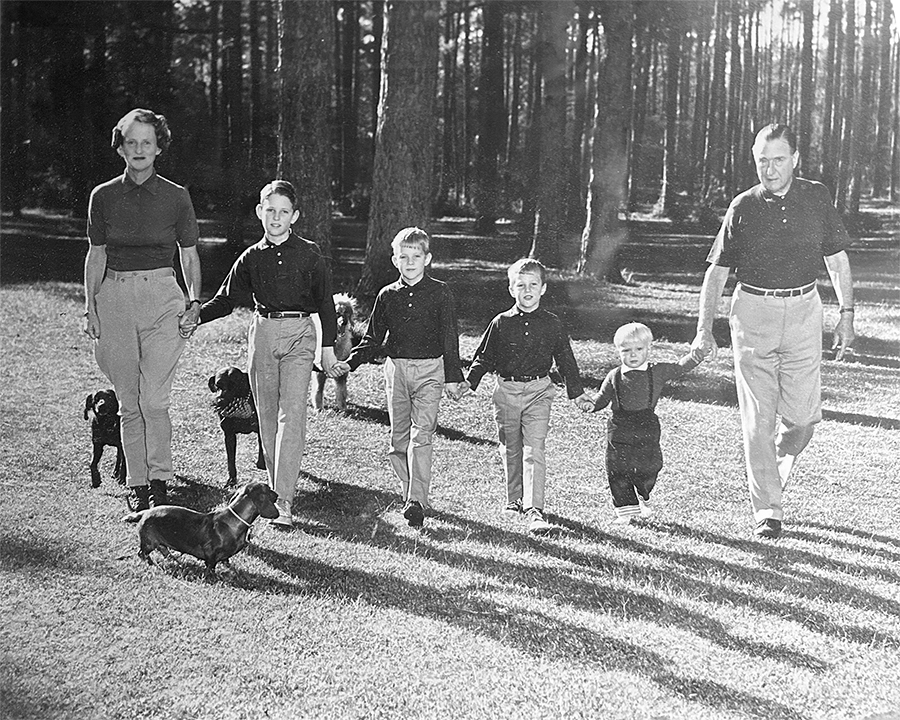

Two miles down Linden Road, west of Clarendon Gardens, lies the nearly 2,000-acre Sandy Woods Farm. Owners Mr. and Mrs. Q.A. Shaw McKean (Shaw and Katharine), having just arrived from Europe, were experiencing a bit of jet lag that morning. Their 6-year-old son, David, was playing in the McKeans’ rambling brick house while his three older brothers — John, Tom and Robert — were away at boarding school in the family’s home state of Massachusetts.

Shaw, a 1913 Harvard University grad and standout polo player, had amassed his fortune in banking and investments. His wife, the former Katharine Winthrop, was descended from Puritan John Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. She’d been a top-ranked tennis player during the late 1930s and early ’40s, winning the 1944 United States Indoors title.

Active participants in big-time Thoroughbred racing, the McKeans maintained an impressive stable of two dozen horses at Sandy Woods. The most prized was Polylad, winner of several important races including the 1961 Massachusetts Handicap in which the 5-year-old horse was spurred to a photo-finish victory by Hall of Fame jockey Eddie Arcaro. With major summer races upcoming, Shaw and Katharine would have been eager to catch up with head trainer John Donahue regarding the fitness of Polylad and his stablemates.

At around 10:30 a.m., when Donahue knocked on the McKeans’ front door, he was carrying more pressing news. A forest fire was burning several miles west of the farm. The operator of a small sawmill in West End had left a saw running while taking a water break. The unattended equipment threw off a spark, which in turn ignited a small brush fire. Before anyone knew what was happening, flames began spreading through the pine forest, supercharged by the wind and tinder box-dry conditions.

There was the prospect that intervening county roads could provide an effective firebreak, keeping the blaze away from Sandy Woods and populated areas. Given the prevailing wind, even if the fire leapfrogged the roads, it seemed likely to follow a path that would keep it north of the farm. While not an immediate threat to Sandy Woods, the situation was worrisome enough that Donahue and the McKeans considered the steps necessary to protect the property and themselves if the fire headed their way.

Meanwhile, Moore County forest ranger Travis Wicker was growing increasingly alarmed. He feared the exceedingly dry conditions, coupled with high winds (gusts between 40-50 miles per hour), were a recipe for disaster. Later, Wicker said the danger became magnified when the towering flames “jumped the old Jackson Springs Road. It got hot (out of control), and we knew we had a monster on our hands.”

It seemed nothing could stop or slow the fire. According to The Pilot, the blaze “skipped over roads and fields as if they weren’t there.” Driven by the wind, long prongs of intense flames licked out in multiple directions. The monster became multi-headed, and it was difficult to predict its precise path. There were fears the fire would strike downtown Pinehurst, then vault into the area’s other populated communities. Moreover, three lesser (albeit substantial) fires were burning in other parts of the county.

Fire departments from Moore County and elsewhere were dispatched to far-flung areas of the Sandhills. Coordinating them presented an organizational nightmare. The emergency code 911 didn’t yet exist, and radios didn’t link the volunteer fire departments to a central command center. “When we needed a rural fire truck to do a particular job, we had to send out another truck to hunt him up and give him the instructions,” said Wicker.

When the wind abruptly swung 45 degrees south, the path of the blaze shifted away from Pinehurst and straight in the direction of Sandy Woods’ stables and kennels. The McKeans and Donahue were suddenly faced with a worst-case scenario. But help was on the way, not only from local fire departments but also the McKeans’ friends and neighbors. Among them was Tom Howe, who hauled Clarendon Gardens’ spraying equipment to the scene.

He and other volunteers endured treacherous drives to the farm, blindly feeling their way down Linden Road through intense, spark-bearing black smoke. Given the near-zero visibility, they risked driving right into the inferno. Two brave responders were forced to dive under their truck and lie flat on the pavement until surrounding flames passed by them.

Donahue’s first priority was the evacuation of the horses. Using Sandy Woods’ own horse trailer along with another furnished by legendary harness racing great Octave Blake, Donahue transported 10 of the McKeans’ 24 horses, including Polylad, to safety. But before the trailers could return for a second load, the flames had reached the paddock area. Donahue faced an intractable dilemma. The remaining horses were doomed if he turned them out into the now fiery paddock. Hoping against hope that the blaze would skirt the stables, the trainer decided holding the frightened horses in their stalls was their best bet for survival.

Tragically, they were doomed. The Pilot reported that “with the gale shifting winds, there was no safety anywhere. In a second’s time, it seemed, the stables were ablaze from heat and flying sparks as well as the kennels, and all were engulfed in the inferno.”

The wildfire now loomed within striking distance of the McKeans’ brick home, a half-mile from the stables. Responders feverishly dug a firebreak trench around the periphery of the house while Howe, horseman Pappy Moss, and firefighters from Vass and Pinehurst drenched the structure and surrounding vegetation.

David McKean, now 65, has vivid recollections of his mother appearing at the back of the house and telling him, “We have to leave right now!” The anxiety in her voice was in such marked contrast to her usual unflappable demeanor that 6-year-old David realized the situation was gravely dangerous.

The McKeans hustled to the family car. On their way out the door, they managed to grab a silver trophy commemorating one of Polylad’s victories and a cherished 18th century oil painting by English artist George Morland.

Exiting the farm proved more perilous than it would have been to sit tight at the house. The farm’s mile-long drive to Linden Road had become impassable due to the fire at the stables, so Shaw and Katharine chose a seldom-used back way through the property that led to Roseland Road. David recalls that as his mother drove down the remote path, “there was a burning tree in front of the car — I don’t remember if it fell as we were driving, or if it was already there — and she attempted (unsuccessfully) to drive over it.” With the fire spitting at the McKeans from the rear, it was impossible to back the vehicle out of danger. David and his parents abandoned the car and ran to an adjacent field.

They were spotted by Pinehurst Harness Track veterinarian Dr. John Peters, who came to their rescue and transported them to safety. The McKeans’ house, though scorched in places, escaped serious damage, but their automobile was burned to a crisp. Also destroyed were Polylad’s trophy and the Morland painting, both left behind in the trunk.

Returning home from Chapel Hill in the early afternoon, Pinebluff Mayor E.H. Mills noticed black smoke in the sky west of Pinehurst. Mills followed the smoke to its source at Sandy Woods. Arriving at the farm, the mayor witnessed the frenzied efforts of volunteers to create firebreaks and he, too, pitched in to help until he was met by reporter Valerie Nicholson, covering the disaster for The Pilot.

“Mayor,” she said, “you better get to Pinebluff. The fire is headed there. Your town could burn up.” Mills ran to his car and drove through the haze toward home. On the way, he pondered how his community of 600 could marshal the resources to repel the fire. Tom Howe, concerned with the safety of his wife, children and farm, also rushed home after the blaze at Sandy Woods was under control.

As the fire moved south toward Pinebluff, it caused considerable damage. According to the Sandhills Citizen, it “licked out a vicious tongue at the farming community of Roseland, two miles from Aberdeen, gobbling up two homes and nearly all outbuildings with some 10,000 chicks in two farmyards.” At the Country Acres subdivision off Sand Pit Road (then Gravel Pit Road), it consumed a house and trailer. “With the fire burning right into the yards,” reported the Citizen, “the homeowners watched in an anxious group from the highway intersection.” Several houses caught fire and responding firefighters beat out the flames.

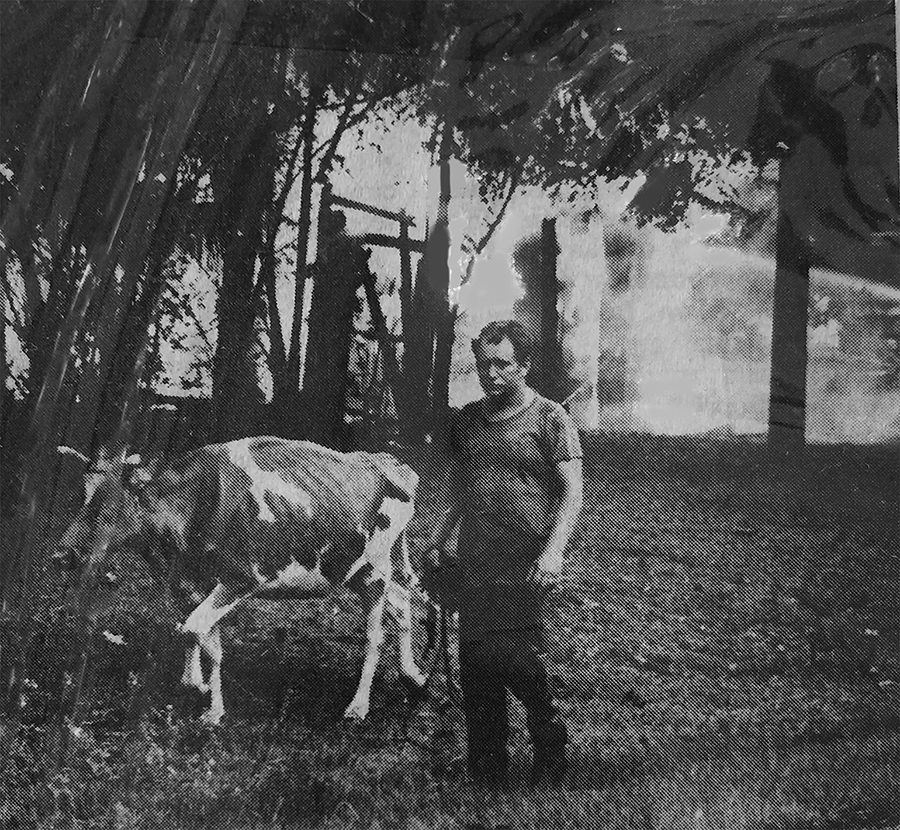

Howe’s route home brought him within sight of Country Acres but, as Tom turned off Route 5 onto Sand Pit Road, he noticed something else. A herd of clearly distressed cows, enveloped by smoke, were straining at the fence alongside the road. A former dairy farmer himself, Tom stopped his truck, cut the fence and freed the cows, who meandered down Route 5 toward Aberdeen.

Back in his pickup, Howe was unable to proceed further because firetrucks blocked progress down Sand Pit. Desperate to assist his family, he maneuvered around the trucks by ramming his pickup through the fence where he’d just freed the livestock, flattening it.

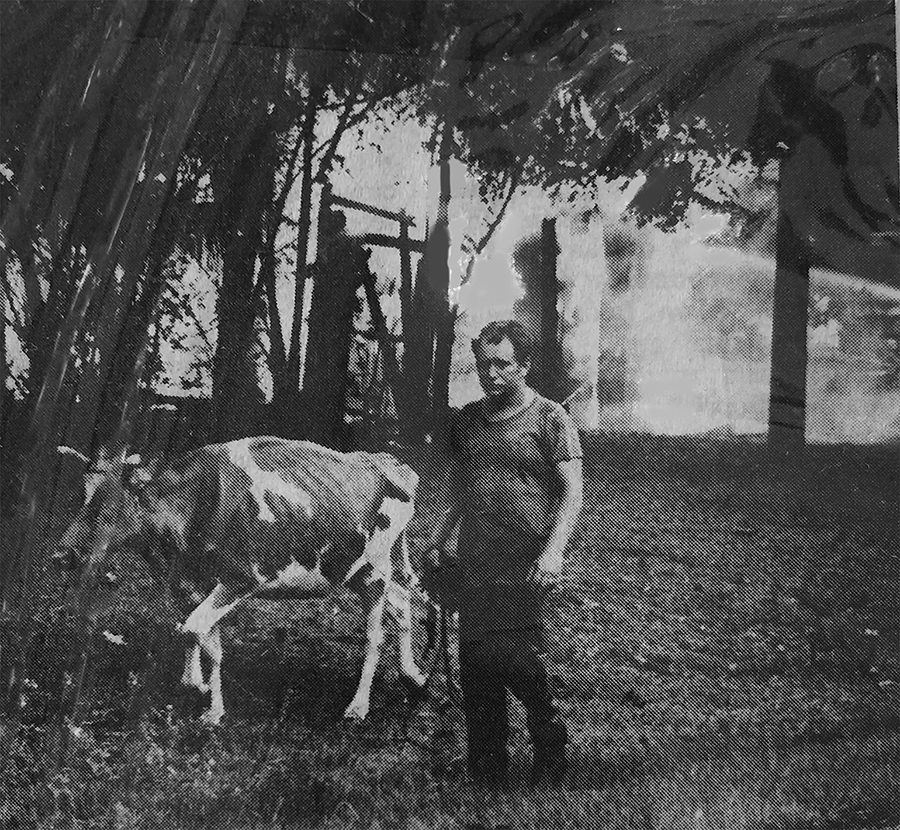

Meanwhile, the fire near Sand Pit Road was bearing down on Elmore Smith’s small dairy operation located off West Baltimore Street just outside Pinebluff. Riding his tractor, Smith, 61, caught sight of approaching dense smoke. Since the blackness seemed far off, he assumed there would be time to take any necessary precautions. Comforted by the fact that his farm and outbuildings were surrounded by open fields and pasture — the woods were 500 feet away — Smith expected his operation would escape serious damage.

Within minutes, a breathtaking tornado of fire catapulted over Smith’s field and came down on his farm. “The sky was filled with fire, boiling in the air, an inferno 100 yards high,” said Smith. The gusty wind had caused the fire to crown, rocketing immense flames skyward a half-mile or more ahead of the heart of the blaze. According to The Pilot, Smith turned out his mule and seven cattle, “smacking them to run off and save themselves.” Elmore’s wife and 18-year-old son ran from the house. The family escaped, but the Smiths’ house, barns, chicken houses, two autos and two pickup trucks were consumed.

After wreaking havoc at Smith’s farm, the fire roared toward downtown Pinebluff. Fire Chief W.K. Carpenter, Jr. sounded the siren. Around 5 p.m., the flames crossed over U.S. 1 at the approximate location of today’s Dollar General Store. It had taken only seven hours for the fire to cover the 14 miles from West End to Pinebluff. According to the Sandhills Citizen, it “leapfrogged from tree to tree and crept relentlessly on the ground through thick pine needles from yard to yard.” A separate prong of the fire jumped the highway south of town.

A veritable army of firefighters from far and near, the District Forester’s office headed by Chief J.A. Pippin, members of rescue squads, as well as ordinary citizens, were poised to fight the blaze in Pinebluff. So, too, were soldiers. It was Tom Howe’s mother, Mary, who persuaded Fort Bragg military brass to authorize aid to the town.

Back at the Howe’s Aurora Hills farm, Nancy was unaware of these happenings when sister-in-law Susan Howe Wain began pounding on her door and shouting, “I need to get on your roof with the garden hose!” According to her memoir titled Dear Owie, when Nancy went outside and looked up, she was aghast to see hot burning embers “falling and dancing on the roof, bouncing up and down, and sailing through the air like they were dissatisfied with my roof and were looking for a better place to land.”

When Tom pulled in the driveway and jumped from the truck, his face, recalled Nancy, was completely blackened and covered with soot, “except for his eyes that peered out from his glasses, like a frog looking for a fly to eat.”

Howe gave urgent instructions, detailed in Dear Owie. “I want you to pack up important papers and a few clothes, food, and water, and be ready to leave. If it gets bad, you all get in the car and drive as hard as you can into the middle of the plowed field across from the house.” Nancy wound up huddled in the field with her boys. While the fire would miss them and their home, Tom’s work was far from over. He rushed to assist others in town where the battle to contain the fire had become a house-by-house struggle.

Hot embers relentlessly dripped from neighborhood pines onto homeowners’ roofs, igniting scores of little fires. Many houses caught fire “again and again only to have the flames put out by workers converging solidly upon them,” wrote the Citizen. Not all the proliferating fires could be extinguished in time to save homes. The residences of Richard Graham and Cad Bennett were destroyed, and countless others sustained severe damage.

Pinebluff’s town council had been scheduled to meet the evening of April 4. Madeline Charles, the town clerk, took the town’s books to her home so she would have them ready for the meeting. The Citizen reported that when the fire jumped the highway, “right in front of the Charles’ home, she searched wildly for a safe place to stash the books.” She wound up stuffing them in the family freezer before running off to fight the fire raging on her lawn.

With a second swath of the blaze threatening the south end of town, the Robbins Rescue Squad and several Fort Bragg soldiers, as a precautionary measure, moved to evacuate residents of the Pinebluff Sanitarium, now long gone. That second swath fortunately failed to reach either the sanitarium or residential areas. Farther south down U.S. 1, David Spence, a machinist whose unique enterprise involved the specialized forging of horseshoes for harness racing horses, was not so lucky. His building and equipment were totally wiped out, causing an estimated loss of $40,000. The Addor area also was hit hard.

So much water was thrown on the fire that the Pinebluff water tank ran dangerously low, and Chief Carpenter ordered his trucks to start drafting from the lake. “We have a fine water system,” said the chief, “but no small town is prepared for a thing like this.”

Those residents not involved in fighting the fire contributed in other ways, manning the Red Cross food station or retrieving lost pets. Carpenter’s own children, Cathy, 13, and Billy Jr., served food past midnight. “They wanted to help,” remarked their mother, Marion, “and I let them stay up even though they are so young. After all, this is their town.”

By 11 p.m. the danger to the town and Moore County was over as the fire blew farther south, ravaging acreage in Camp Mackall before finally petering out at Drowning Creek. The final toll was staggering: 26,000 acres burned, two-thirds of them woodlands; 5,000 acres of planted areas lost; engagement of 4,000 firefighters; the razing of 14 dwellings, 25 barns, two business buildings, and the death of an untold number of animals. Fortunately, no human lives were lost.

The nightmare wasn’t over for Tom Howe. Katharine McKean asked him to bury the horses destroyed at Sandy Woods. Howe told his wife it was the most gut-wrenching experience of his life.

Howe eventually started a nursery business at Aurora Hills, which he operated until his death in 2015. His two sons still run the business. Nancy continues to live in Moore County, as does Susan Howe Wain.

The McKean family still owns Sandy Woods, though the stables no longer house racehorses. Shaw and Katharine have long since passed on. Son John lived at the farm until his death in 2019. His brother Tom, a retired Massachusetts attorney, now looks over the property. Brother David, who escaped the fire that day, became a diplomat, serving as ambassador to Luxembourg and director of policy planning for the Department of State. He’s a successful author of books about 20th century American history.

Could the wildfire of 1963 happen today? One factor that reduces the chances of a similar catastrophe is the increased use of controlled burning. Forest fires require fuel to accelerate and, especially in a longleaf pine forest, much of that fuel comes from the wiregrass and scrub oak underlying the trees. Jesse Wembley of West End, whose mission locally is educating area landowners and farmers about the benefits of controlled burning, says, “We have to learn to live with fire. Particularly here in the Sandhills, it is part of the natural process. With it, we get an improved ecosystem and peace of mind.”

There was little piece of mind that day in April. Lifetime Pinebluff resident John Mills, son of the former mayor, says, “It is a miracle the fire missed Pinehurst and a double miracle it didn’t burn all of Pinebluff to the ground.” PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.