Shooting the Stars

Spacing out with a Sandhills photographer

By Jenna Biter

Photographs by Larry Pizzi

Feature photograph: The Western Veil Nebula or Witch’s Broom is the remains of a star that exploded more than 10,000 years ago

Left: Comet NEOWISE C/2020 F3 over Lake Auman in Seven Lakes

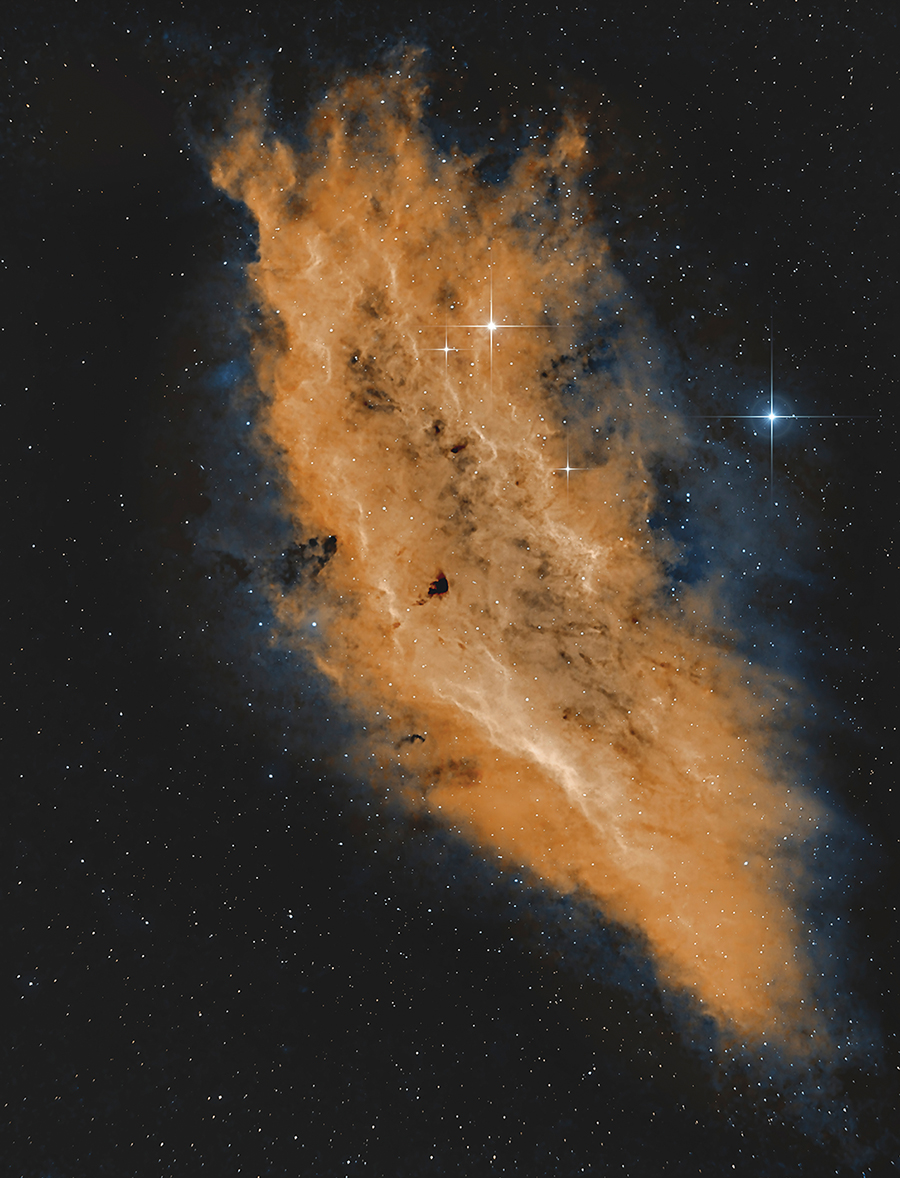

Right: NGC 1499 the California Nebula is shaped like the Golden State. It’s a nearby neighbor — only 1,000 light years from Earth.

At the end of another day, the Earth turns its face from the sun, and dusk stretches its long arms over the horizon, tucking half of the globe under the heavy blanket of night. In the thick of North Carolina pine country, drowsy towns go dim but not yet dark, like fires burnt to embers.

Somewhere in Seven Lakes, on a wide corner lot occupied by an agreeable yellow house, one Northerner-come-south seems immune to the lullaby of night.

As a neighbor’s kitchen light goes out, the yellow house stirs. Its garage door rolls up, and a man dressed in a vacation-style shirt fit for Georges Seurat’s La Grande Jatte steps onto his driveway under the purple fresco of Starry Night. He pushes a tripod fixed atop caster wheels into the middle of the blacktop, then steps back to eye the mechanical spider. It has one oculus instead of eight, a 21st-century Cyclops capable of probing the heavens.

Larry Pizzi rolls the telescope forward and back, left to right, manually repositioning the tripod before fine-tuning the focus and field of view with swipes on an iPad.

“My telescopes, you don’t look through them,” Larry explained earlier in the living room inside the agreeable yellow house. Antique clocks chattered from the walls, their pendulums tick-tocking as they waved hello and goodbye. Like a chorus of teakettles whistling with steam, the clocks burst into chirps and chimes and dings at set intervals — like clockwork.

Left: SH2-275, the Rosette Nebula, is a star incubator. Its gasses and dust allow stars to form in it.

“Sorry about that,” Larry said.

“That’s his other hobby,” his wife, Wendy, said, seated on the floor. Beside her, their small pooch, Dibley, champed at a stuffed alligator. He ripped with such enthusiasm that he seemed to understand the irony.

“There are a hundred clocks here, and a hundred still in storage in the garage,” Larry said, then returned to his other passion. “My telescopes, they’re like really big camera lenses.”

Larry’s dad, Joe, surprised him with his first telescope when he was in fourth grade. He didn’t get his first camera until a year later. Of course, Larry unscrewed screws and peeled back metal housings to investigate both gadgets, as little boys are prone to do.

“I was good at taking things apart, not really great at putting them back together,” he admitted. “I ruined that camera.” His tone sagged with momentary regret.

“God bless digital cameras,” Wendy cracked, bringing her husband back.

He grinned. “I had to know how it worked, you know?”

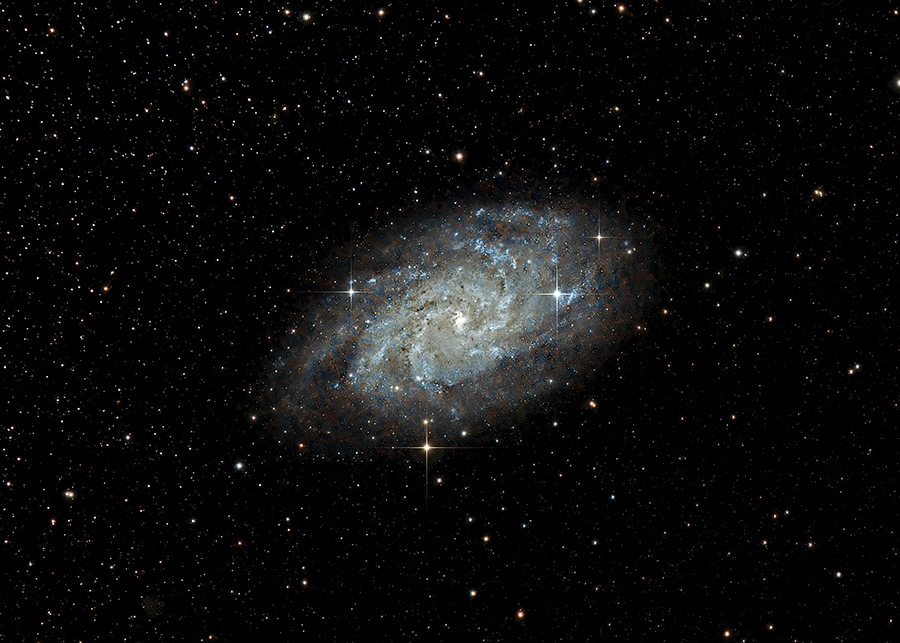

Left: M33, the Triangulum Galaxy

Right: M45, the Pleiades or the Seven Sisters is easy to spot with the naked eye in the constellation Taurus, the Bull.

Larry kept up with photography through three careers and the lion’s share of his almost 70 years, focusing mostly on eye-level wonders, from the covered bridges of Pennsylvania Amish country to Appalachian waterfalls. It was almost as though he had forgotten to look up.

“It was in high school that I really got into astronomy and started a little bit of astrophotography,” Larry said. “But then life intervened for about 40 years.”

It wasn’t until 2018, when the Pizzis moved south to the Sandhills, that Larry resurrected a telescope from the bowels of his garage and days gone by.

“Clear skies,” he said. “We came from New Jersey.”

“Plus, you were retired when you moved here,” Wendy pointed out. “You no longer had your day job.”

After serving in the Army for 21 years and working with nonprofits for another decade, Pizzi retired from his third and favorite career in 2016. A classics major, he taught English and Latin for a dozen or so years in the part of New Jersey that thinks it’s Philadelphia.

Back outside, Larry, though no longer a teacher, diagrams his telescope with the quiet confidence of a veteran professor lecturing on the human skeleton. “This is the main camera,” he says, pointing to a cylinder at the butt of the telescope’s yard-long tube where the eyepiece would normally seat. “This is the guide telescope, and this is a guide camera.” He finishes the anatomical tour before gazing up at the now-black sky.

“Tonight’s target is a nebula,” he says. Like many of the clouds swirling with cosmic dust and gas, this nebula located deep within the Cepheus constellation, beyond the reaches of the naked eye, has no name, only a designation: NGC 7822. Nebulae reveal the life cycle of the gods. Either they’re the birthplaces of the stars, like this night’s target, or they’re like overturned funeral urns, spilling the ashes of luminescent giants into the void. On this particular night, this particular nebula arcs through the band of sky perfectly visible — between rooflines and the crowns of longleaf pines — to the Cyclops in the middle of Larry’s blacktop.

Left: Part of a large complex of nebulae in the constellation of Orion. Upper left is the Flame Nebula. The dark formation is the Horsehead Nebula. The largest is M42, the Great Orion Nebula.

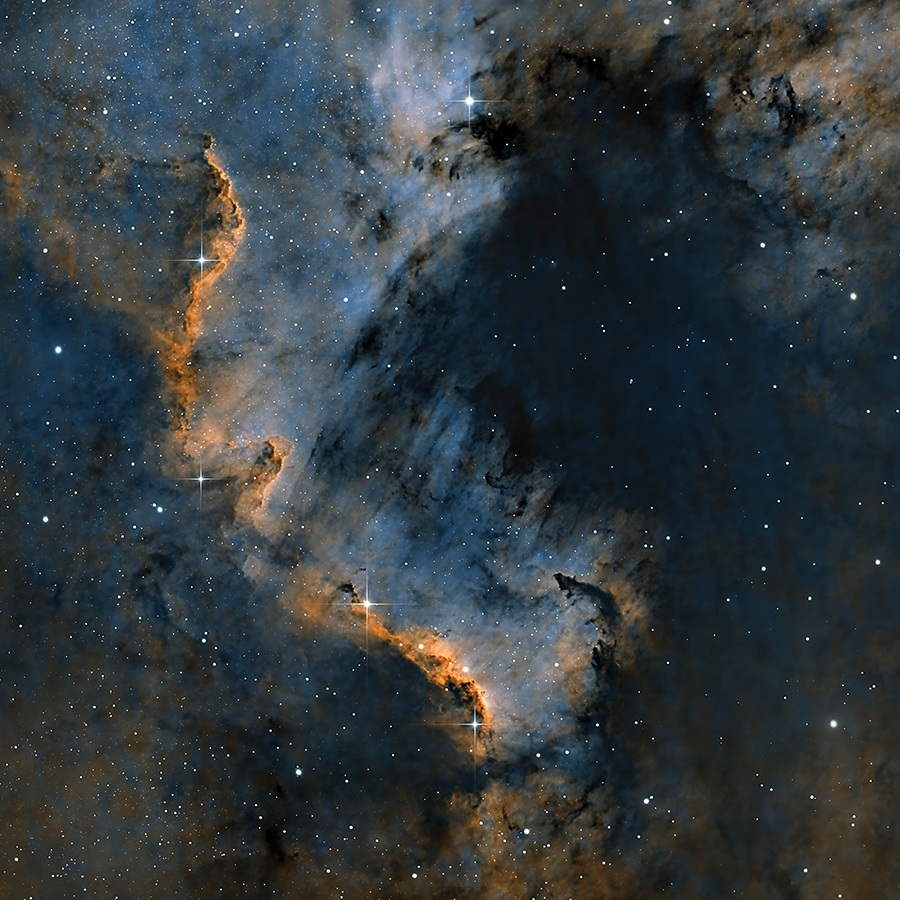

Right: A part of NGC 7000, the North America Nebula. The bright part is called the Cygnus Wall, a formation of very hot gasses and dust actively giving birth to stars.

“Taking the pictures is actually the easiest part,” Larry says. Once the telescope locks onto its target, the oculus, like a landbound guardian angel, watches the cosmic traveler move through the sky, snapping photos all the while.

“When you’re taking a picture, you don’t take a picture,” he says, hanging onto the ‘A.’ “You take dozens if not hundreds of short exposures.” Larry usually shoots 100 to 150 frames in a session. “And sometimes, you do it over multiple nights, the same target.”

After shooting, Larry stacks the frames on top of each other like a digital layer cake. Then he attends to each frame individually, checking them for the taillights of stray aircraft or the glow of the neighbor’s kitchen, before combining the unflawed frames into the final photo.

“It’s at least eight to 12 hours to process the photos,” he says. The process happens on a pair of computer monitors at a corner desk in a corner room that Larry dubbed “the digital darkroom.” Of course, a clock chatters happily from the wall behind.

“The way I take pictures is the exact same way the James Webb Telescope takes a picture,” Larry says. “Webb is just a little more sophisticated.”

Once the telescope finds its target, Larry turns away. He wheels around shooting a green laser into the dark and circles constellations. There’s Draco, Cygnus the Swan, and the W-shaped Cassiopeia. He points out stars like a maestro lost in the music of space and time, conducting the celestial orchestra.

“I think the reason he’s rekindled this passion is that retirement is a challenging season in life, and I think that this has made retirement a plus instead of a minus,” Wendy says.

“This is a great outlet,” Larry says. “I think I’m a frustrated artist.” PS

Jenna Biter is a writer and military wife in the Sandhills. She can be reached at jennabiter@protonmail.com.