By Nan Graham

We scrambled flat on our stomachs, wrestling the bulky cardboard box from under the looming four-poster bed. My cousin Anne and I are not teenagers . . . we’re not even middle-aged . . . so it was a grim spectacle of struggling grayheads, who risked never getting vertical again, to do this.

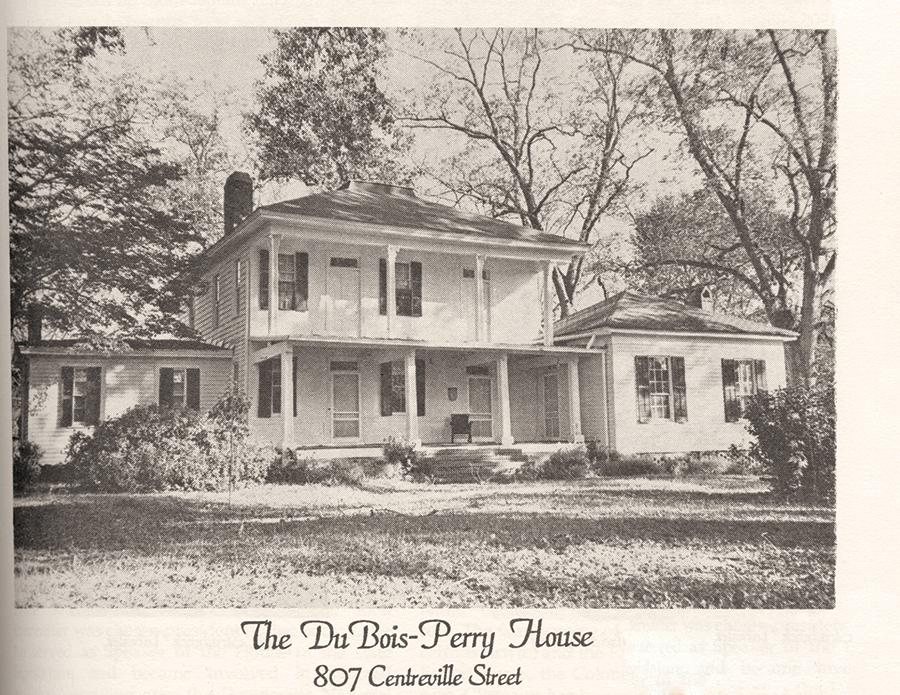

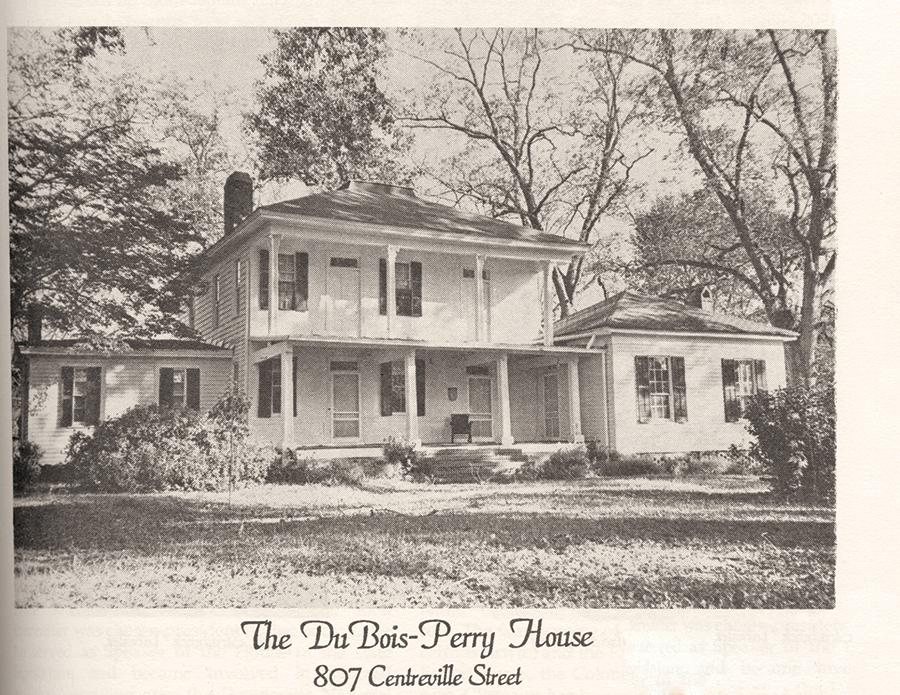

The musty papers and letters of one of the most colorful of our relatives, our great-aunt, Martha Strudwick Young, a diminutive professional writer, born the year after the War Between the States began, contained some surprising new information. Cousin Anne had never looked in the boxes since her mother’s death in 1970, some 40-plus years ago. We were only a few miles from Martha Young’s birthplace in Hale County, Alabama, at a place called The Pillbox a few miles out from Greensboro, Alabama, and my visit had prompted questions about the writer’s childhood. We were well into the second round of iced tea when Anne remembered the flat coat box stored beneath the bed.

We knew from family stories that Martha’s early years were spent riding in the carriage with her father, Dr. Elisha Young, through the Hale County countryside as he made his rounds and tended to his patients. A surgeon in the Confederate Army stationed at Fort Morgan in Mobile — and imprisoned in New Orleans after the fall of Mobile — Dr. Young returned to his little family after the war to practice medicine in Greensboro, Alabama. A born storyteller, the doctor entertained the little girl with stories of making quilts with his black nurse as a young boy, eyewitness accounts of battles on Mobile Bay, and starving troops in the Alabama countryside as the father and daughter roamed the county in his buggy on house calls. He told of performing the first ever successful cutting and suturing of a carotid artery on a man stabbed and brought to his kitchen table in the middle of the night. The patient survived the procedure in the makeshift operating room. Dr. Young said that early quilt-making, common among young Southern boys in the 1860s in the county, gave him his surgical skills.

Martha had a quick ear for the rich dialect of the black folks at home and in the rural countryside. She was spellbound with their musical language and loved their tales of witches, wicked spells and ha’nts, and stories of talking birds. She absorbed the speech, its cadence and energy, of the black storytellers. Martha took mental notes on the actual calls and songs of birds of her native Hale County along the wooded roads. She was a good listener and had an excellent ear for mimicry.

She began to write and craft the oral tales told to her by blacks in her household and those she knew in the small community of Greensboro. She listened to the musical calls from the men and women who peddled fresh butterbeans and field peas ( “Fe-ull Peeas. Yas. Freee-sh Pleeeez . . .”) from carts on the dusty streets of her neighborhood. She listened to the ghost stories of the cook Chloe in the family kitchen house and to the animal stories of Isham, who helped with the horses and cows. She wove the tales into lyrical and haunting stories about sparrows’ chatty conversations with crows and baby robins squabbling among themselves. And useful warnings that picking peaches from the tree after sundown would kill the tree. Martha added her own keen observations of nature in Greensboro and the countryside around it, and incorporated the sounds of the birds and creatures as an integral part of her stories.

Being the oldest child of the eight siblings (of whom only five survived), Martha as a young adult in her 20s inherited the role of caretaker of the family at her mother’s early death in 1887. Her physician father could never have managed without his eldest daughter’s capable and no-nonsense discipline of her younger, motherless brothers and sisters. Martha practiced her bird calls and storytelling skills on the younger children, who were enthralled at their big sister’s tales of the talking buzzards, singing bats and swamp witches. Amazingly, she continued her writing despite being mistress of a large household and surrogate mother to a brood of children ages 7 into pre-teen.

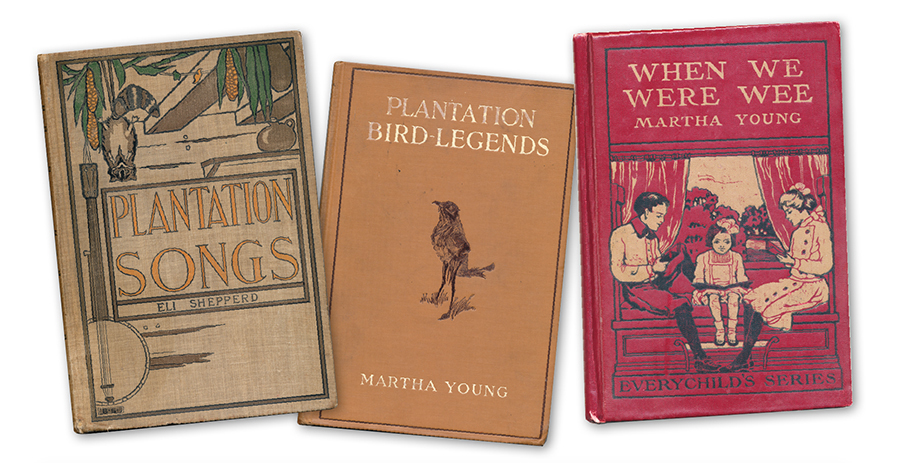

And after raising her younger brothers and sisters, Martha, or Tut (rhymes with foot), as the family called her, decided that the single life was the life for her. As she always replied to inquiries about her marital state: “No, I am not married. I shall stay . . . forever Young!” (Her early sibling-rearing may explain the decision of the many spinsters out there, especially around the turn of the century.) Granddaughter of an Alabama anti-Secessionist, she had a college degree and was encouraged in her writing by her family. She started her career under the pseudonym Eli Shepperd, since young women from the South were not usually accepted in the male-dominated literary scene.

She began submitting her dialect bird stories to the New Orleans Times-Democrat, which first published her work in 1884, a Christmas story titled “A Nurse’s Tale.” Other Southern newspapers published the prolific writer’s stories.

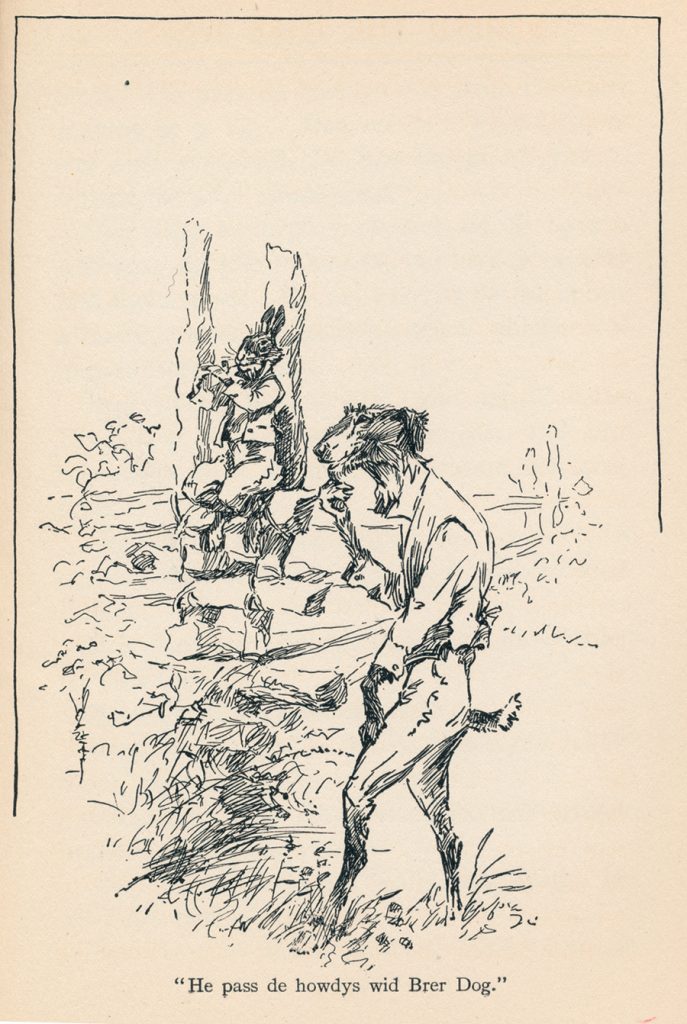

The creator of Brer Rabbit and the Tar Baby, Joel Chandler Harris, gave high praise to the dialect writer, according to one newspaper account and even collaborated with Martha on one of his Uncle Remus collections. Joel Chandler Harris himself wrote: “Her dialect verse . . . is the best written since Irwin Russell died. Some of it is incomparably the best ever written.”

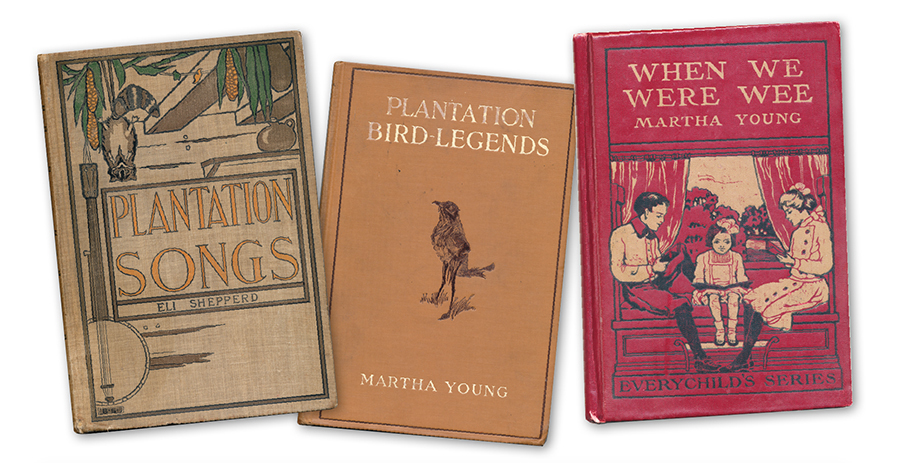

Her first book, with the catchy title Plantation Songs for My Lady’s Banjo and Other Negro Lyrics and Monologues, was published in 1901, still under the pseudonym Eli Shepperd. The originator of Brer Rabbit contacted the writer under that name. Joel Chandler Harris invited “Mr. Shepperd” to join him at a small hunting lodge at his Georgia home, Eagle’s Nest, to work on a collection of folk stories. It was a secluded spot and Harris felt it would be a productive collaboration. Naturally, Martha revealed her identity as a lady and responded that she hardly thought that Mrs. Harris would approve the plan. The two writers did eventually collaborate, but not in the secluded setting first suggested to Eli Shepperd!

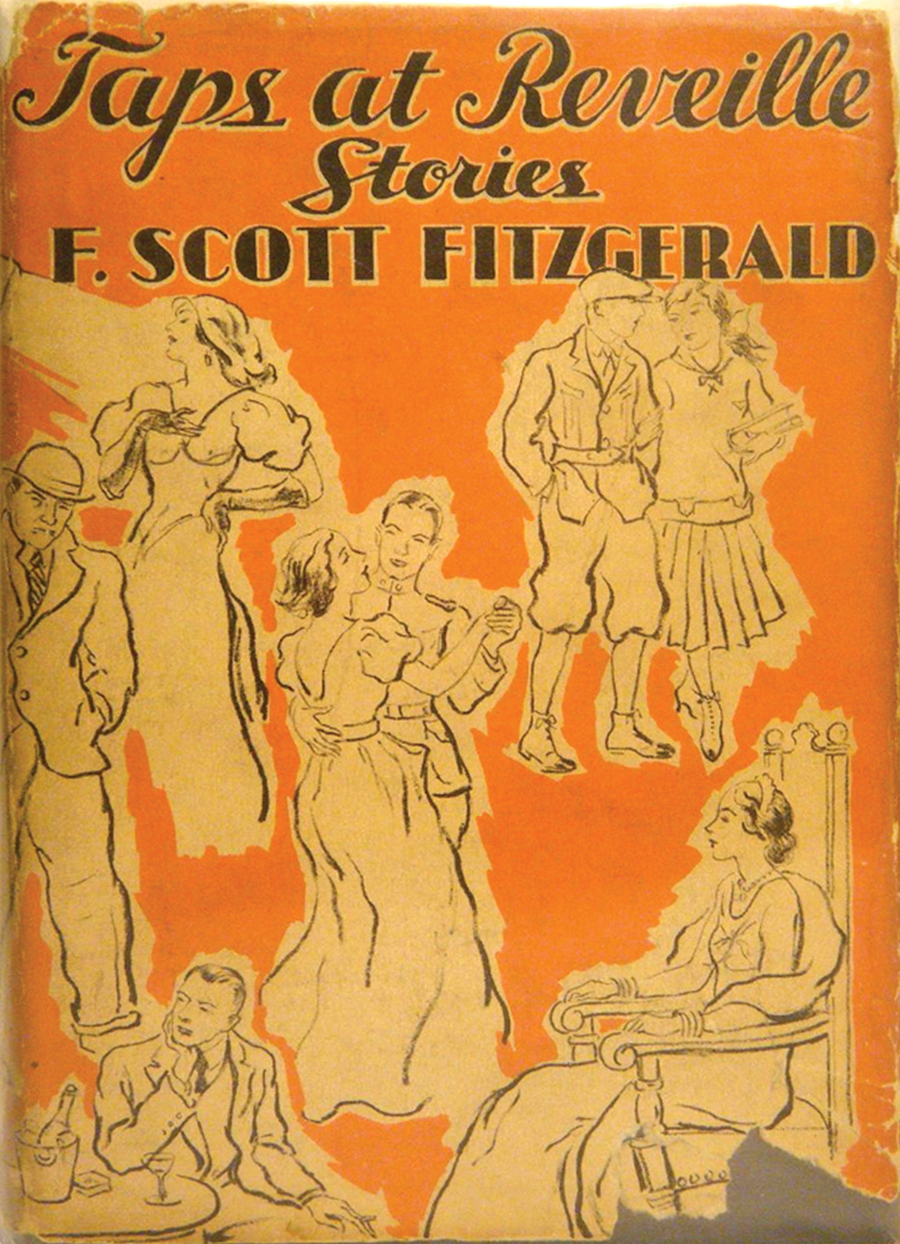

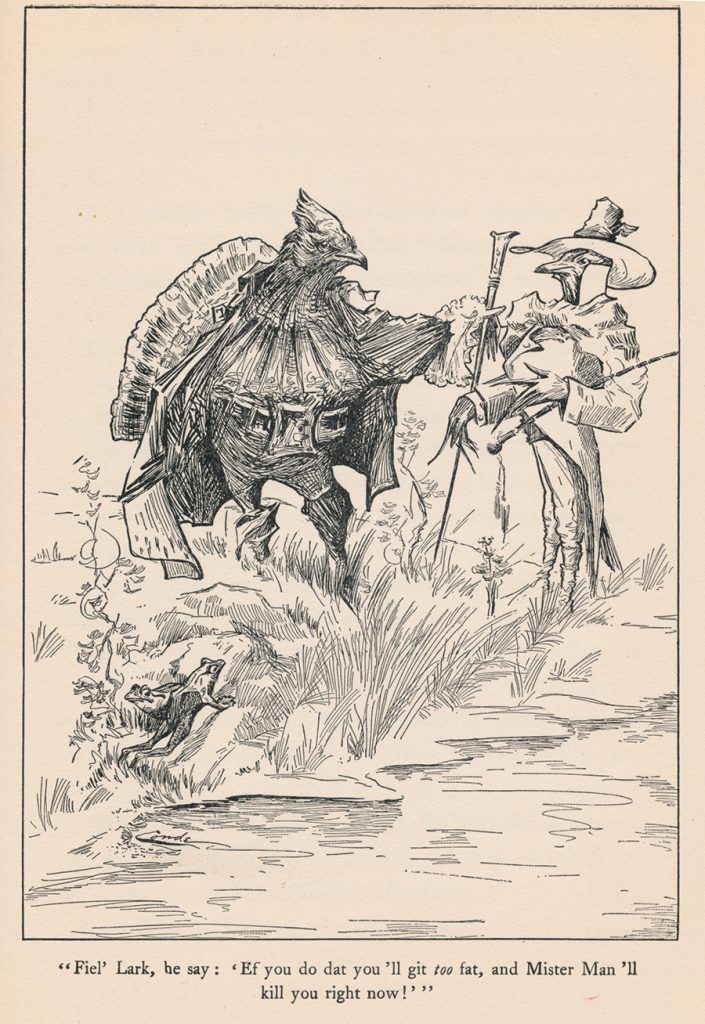

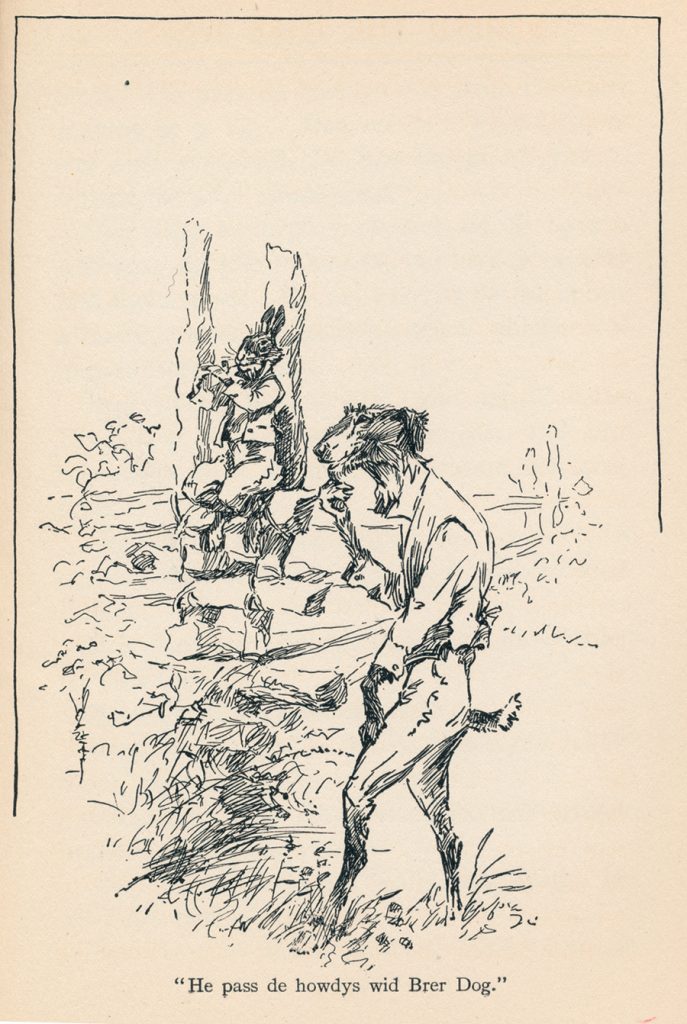

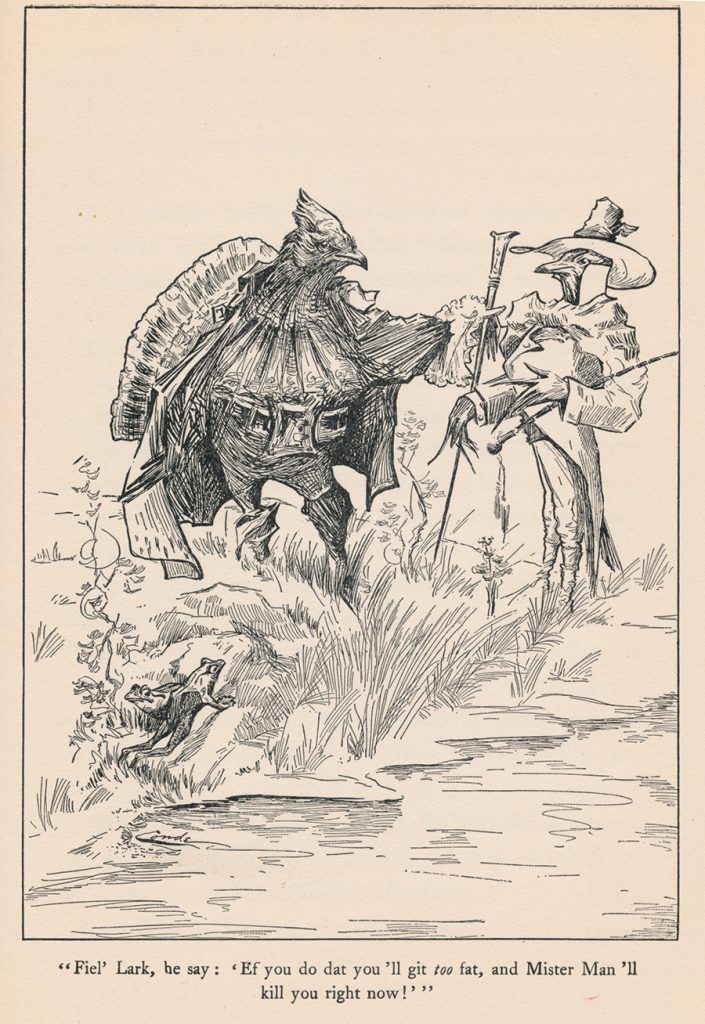

More books followed Plantation Songs: Plantation Bird Legends (1902), Bessie Bell (1903) (later re-released as Somebody’s Little Girl in 1910), When We Were Wee (1912), Behind the Dark Pines (1912), Two Little Southern Sisters (1919), and Minute Dramas: Kodak in the Quarters (1921). Another Martha Young book, Fifty Folklore Fables, was reviewed and mentioned in publicity releases but is unable to be located. Plantation Bird Legends and Behind the Dark Pines are both illustrated with pen-and-ink drawings by J.M. Conde, the artist used by Joel Chandler Harris. Besides her eight published books, numerous articles and stories by Martha appeared in such magazines as Woman’s Home Companion, Cosmopolitan and Christian Advocate. Cosmopolitan, begun in 1886, was a family magazine at the time (a far cry — not even in shouting distance — from the modern Cosmopolitan) and featured such established writers as Jack London, Edith Wharton, Willa Cather, Theodore Dreiser and later H.G. Wells and George Bernard Shaw. (In 1965, Helen Gurley Brown, author of Sex and the Single Girl, revamped the family magazine of Martha’s day, zeroing in on women’s issues, becoming the familiar magazine we know today as the sexy Cosmopolitan.)

Martha Young reached her literary peak in the first decade of the 20th century. Her whimsical bird stories in African-American dialect were a runaway hit. Her books were a smash across the country, North and South. The Pittsburgh Gazette was among those who raved about her Plantation Bird Legends: “What the Grimm Brothers did, taking from the lips of unlettered peasants the folktales of the foretimes and setting them down for the delight of the after age, has now been done by Miss Young.” Martha’s other animal tales included such titles as “Why Brer Possum’s Tail Is Bare,” “Mr. Bluebird’s Debt,” and “Why Mr. Frog Is Still a Batchelor.”

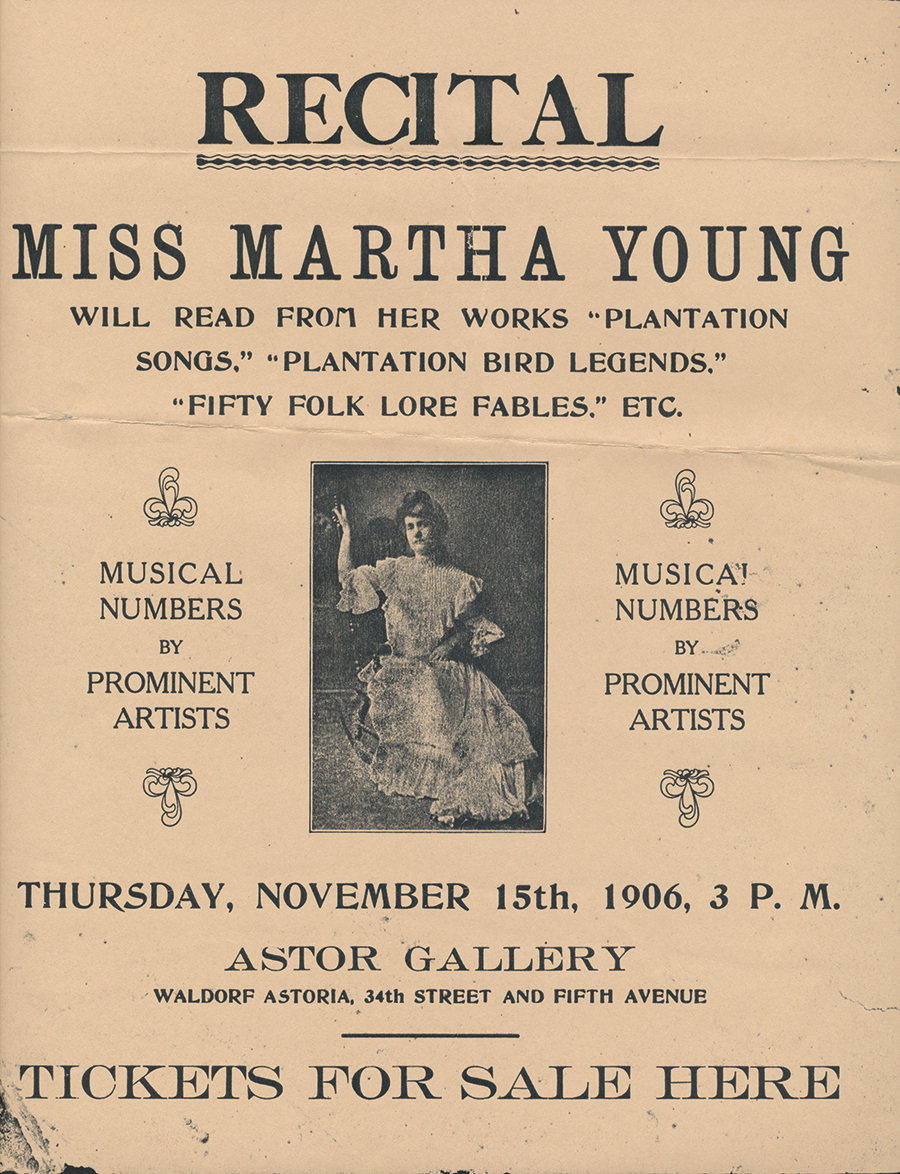

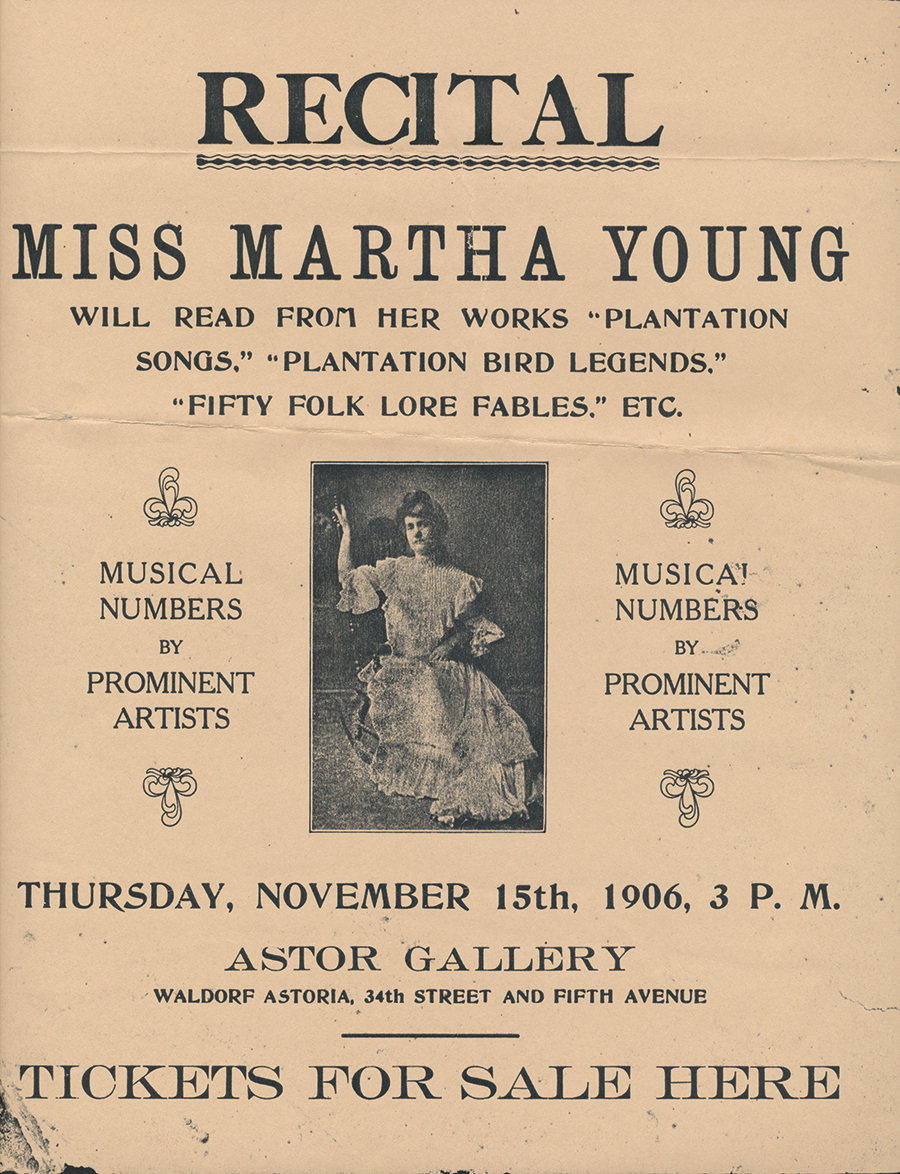

Martha even performed live at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in 1906, reading stories and poetry in dialect from her published books and actually performing bird calls and trills to the audience’s amazement and delight. Other “musical numbers by prominent artists,” not mentioned by name, were also to appear on the evening program. She became a popular speaker in the East and almost all reviews of her events laud her delivery and lively presentations with comments about her distinctive voice.

OK. It WAS a different era, but I like to think Martha was an early Susan Boyle — without the bad hair — an unlikely candidate for public success having been raised in the tiny town of Greensboro, Alabama. Tickets for the performance were $1, the equivalent of about $27 in today’s currency, when the 1906 worker’s wage was about $300 per year and the average hourly wage 22 cents an hour.

Her Waldorf-Astoria poster shows the studio photograph of the petite 28-year-old Martha in an elegant pose. Reality was that in 1906, Miss Young was well into her 42nd year and a bit more stout (as they say in the South) than the slender young woman pictured.

Tut even had an offer to perform in vaudeville in New York, but politely demurred. (I am certain her lips were pursed when she did.)

She was quite prolific: plays, novels, stories for education journals and poetry, some even feminist. The poem “Uncle Isham” written under her pen name is narrated by an African-American to suffragettes who laughingly says ladies, don’t bother. He complains that he got the vote, but it didn’t change a thing . . . so never mind!

Hollywood called early on. One of her books, Somebody’s Little Girl, caught a Hollywood mogul’s eye. His office called the author Martha Young. As it turned out, it was not her story they were interested in, it was the title. Could they purchase the title alone, they asked. Martha was mortified at the idea. “Of course not,” she replied. “I would just as well sever my child’s head from its body as sell my title from its story.” (It does make you think of Gloria Swanson’s has-been character in Sunset Boulevard when she thinks Cecil B. DeMille wants her for a movie comeback, when he actually only wants to borrow her vintage 1929 Isotta-Fraschini touring car.) Hollywood went elsewhere for a title, and unfortunately, we do not know which movie resulted after these failed negotiations with Martha.

One family story centered around Martha’s ferocious love of coffee and her prodigious consumption of the drink. She downed a dozen or more cups a day, but one Lent she decided to deny herself her most precious beverage. She announced what she was giving up for Lent with an unseemly pride to family, friends and neighbors: No coffee for 40 days and 40 nights.

About a week into her extreme Lenten abstinence, her brother came to see her. The door was open; he called . . . no answer. He wandered through the empty house until he heard a tiny voice from the closet. “In here, Elisha.”

He opened the door and saw his sister sitting on a straight chair in the darkened closet, drinking a cup of coffee.

“Tut,” he chastised, “Don’t you know the Lord can see you, even in this closet?”

“Of course I do,” she said, taking another sip. “But the neighbors can’t.”

Her Presbyterian brother closed the closet door and left her to her secret sin.

Tut became the family eccentric, a standout in a host of relatives competing for the title. Martha Young never voted in any election, even after women won the right to vote. She had been born the year Alabama seceded from the Union. Alabama came back after Appomattox . . . Martha never did. She was of the notion that she was not a citizen of the United States and accordingly, was not an eligible voter.

Her tiny feet were a particular source of pride. And with reason. In Martha’s day, Birmingham was where you shopped when you wanted something grand. It was Alabama’s answer to Paris. Passing the city’s finest shoe store, Tut stopped to read the display sign:

TRY ON CINDERELLA’S SLIPPER

You Might Be the Lucky Winner of a Pair of Shoes of Your Choice!

Tut strolled into the shop and sat while the salesman slipped the crystal slipper on her foot with ease. A perfect fit! She selecting the most cunning — and expensive — shoes on display. With shopping bag in hand, she waltzed out to meet her family for the triumphal return to Greensboro. Needless to say, she and her feet were the envy of every female in town. In all her photographs from that day forward, she managed to display her Cinderella foot peeking out from her floor-length dress.

Also vain about her small hands, she always posed them prominently in every picture. At one dinner party, she took a stroll in the garden at her host’s home at dusk. When she reached to touch a flower, she was bitten by a small garden snake. She rushed to the house, where she dropped to the sofa, crying, “My hand! My beautiful little hand. Ohhhh!” She held her hand aloft for inspection. As the guests gathered round, Martha put on a performance her fellow guests never forgot. Sarah Bernhardt would have been proud. Talk about how to sabotage a party. Tut’s uber-vanity quickly became part of the family history.

Local lore in Greensboro claims that Margaret Mitchell came calling on Tut in the 1930s. She was looking for advice on African-American speech patterns and dialect on a certain book she was writing. There is no evidence of this research visit by the author of Gone with the Wind except three local Greensboro sources who have heard the story handed down.

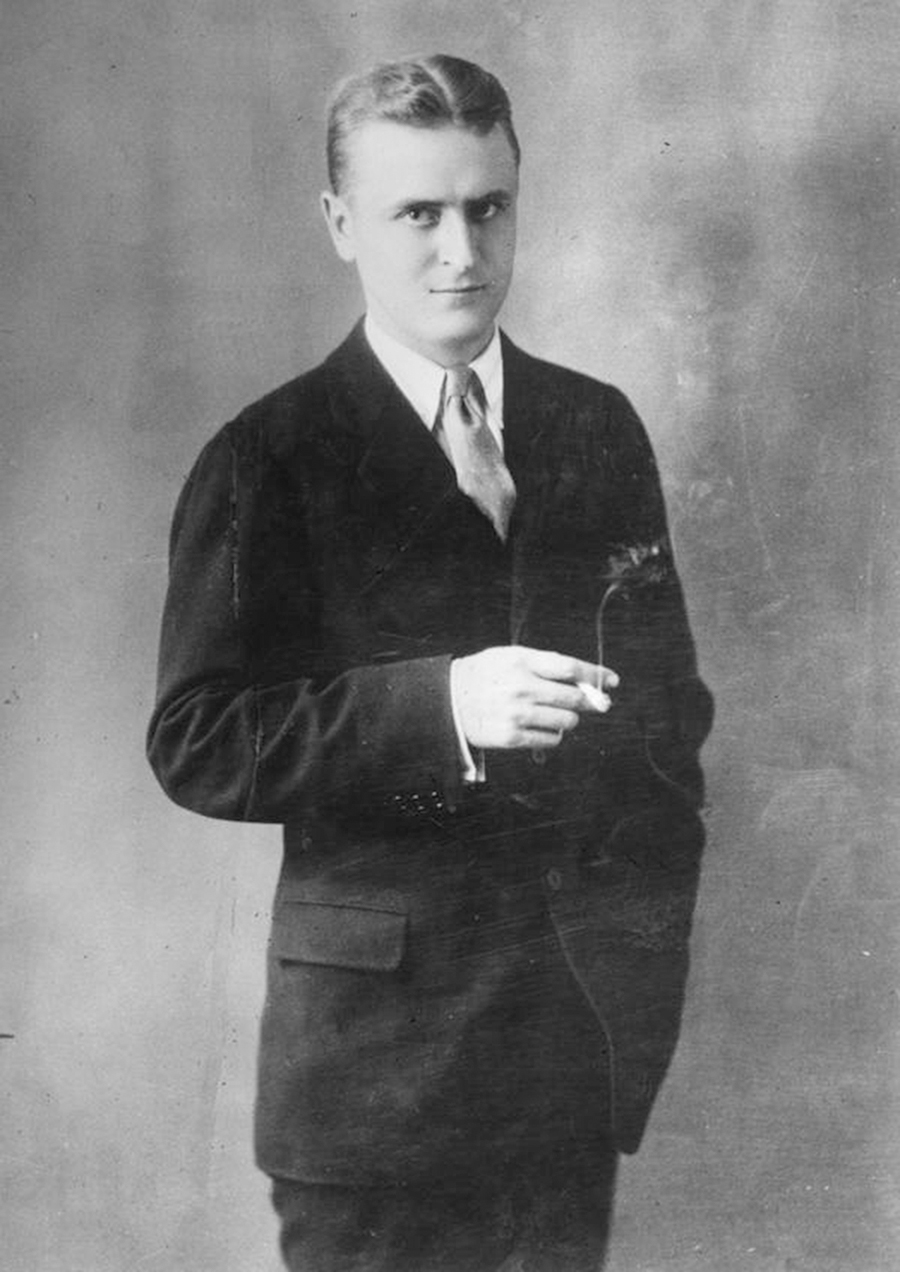

In 2006, a call came from Hollywood asking if I had or knew of any recordings of Martha Young’s voice. Production was beginning on a new film about Zelda Fitzgerald. They had heard of Martha Young’s work and were anxious to hear her Deep South accent for resource material for the film. Alas, although there is mention of her recordings in several writings about her, none could be tracked down.

The aging author did not mellow with age. One of my favorite stories about Tut was about her later years, when she developed diabetes in her old age and would not go to the doctor for follow-up visits.

“But Martha,” her friends insisted, “You need to get your blood checked.”

“I certainly do not,” she replied, drawing herself up imperiously. “I can assure you, I have the very best blood in Alabama.”

As the century rolled on and literary styles changed, Martha turned from writing lively animal stories to religious poetry and full-length plays as her next endeavors. It was an unfortunate career move. Martha’s religious poems are excruciatingly bad, but despite that fact, they continued to appear in magazines and newspapers. A few of these poetic gems’ titles: “Buddha’s Lilies” (Tut was an avid Episcopalian) and “Sermon on the Mule,” “Blessings of the Magnolia,” and “Sermon Against Bad Language.” The tedious plays (my personal favorite was Dice of Death) and her novels were never published, thank God, and now languish in a library’s special collection archives.

In the late 1930s, Walt Disney contacted Martha’s agent, according to correspondence found under that bed. The Disney studio was interested in animating her bird characters and stories. The elderly author had almost stopped all writing by now, but her agent’s letters were wildly optimistic. Disney, flush with the huge success of the 1937 release of Snow White, was working with Martha’s bird stories and had come up with some ideas on using them in a Disney full-length animated feature film.

“Oh no,” wrote Martha after reading one Disney adaptation, “Sis Sparrow would never say such a thing! No, no, Brer Crow could not possible perform such a dance . . . it’s all wrong. Wrong!” The imperious author was unyielding to the siren song of Hollywood.

Negotiations broke down after several years, the letters reveal. The headstrong Miss Martha Young proved a tough cookie. Five years later, Disney came out with Song of the South, the mix of animation and real film characters. Aunt Tut died in 1941 and the correspondence recording the futile negotiation with Walt Disney was stashed under that poster bed in Hale County, where it remained until a few summers ago.

Sis Sparrow could have been singing “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” while Bruh Crow and Martha Young’s other bird characters danced, if only Proud Martha had not been so mule-headed. She coulda been a contenda . . . maybe!

Acknowledgment for the culture and dialect of the black stories is a growing movement in the literary world. Zora Neale Hurston’s Barracoon, the true story of a survivor of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, was refused by editors in 1927 because of its dialect narrative and is now published with a scholarly introduction.

Aunt Tut is not completely forgotten. Almost all her early works have been republished by academics and folklore enthusiasts with original titles and author Martha Young’s name. And so the original stories remain in print.

Virginia Hamilton, a noted African-American author, read some of Martha Young’s folktales, rewrote them (it is almost a translation from the dialect) and had famed Barry Moser illustrate the stories. When Birds Could Talk and Bats Could Sing, published in 1996, is a beautifully illustrated book of Martha Young’s stories that are a joy to read today. ( My only complaint: The book is titled by Virginia Hamilton. As an academician, Hamilton surely knew that the correct way to title the book would be: By Martha Young as retold by Virginia Hamilton.) There is a brief explanation of Martha Young on the last page of Hamilton’s book. The beautiful new version of Martha Strudwick Young’s fanciful tales of talking sparrows and dancing crows is thankfully preserved. PS

Nan Graham is a regular Salt contributor and has been a local NPR commentator since 1995.