Three friends fondly remember a rip-roarin’ ring-tailed artist

By Stephen E. Smith

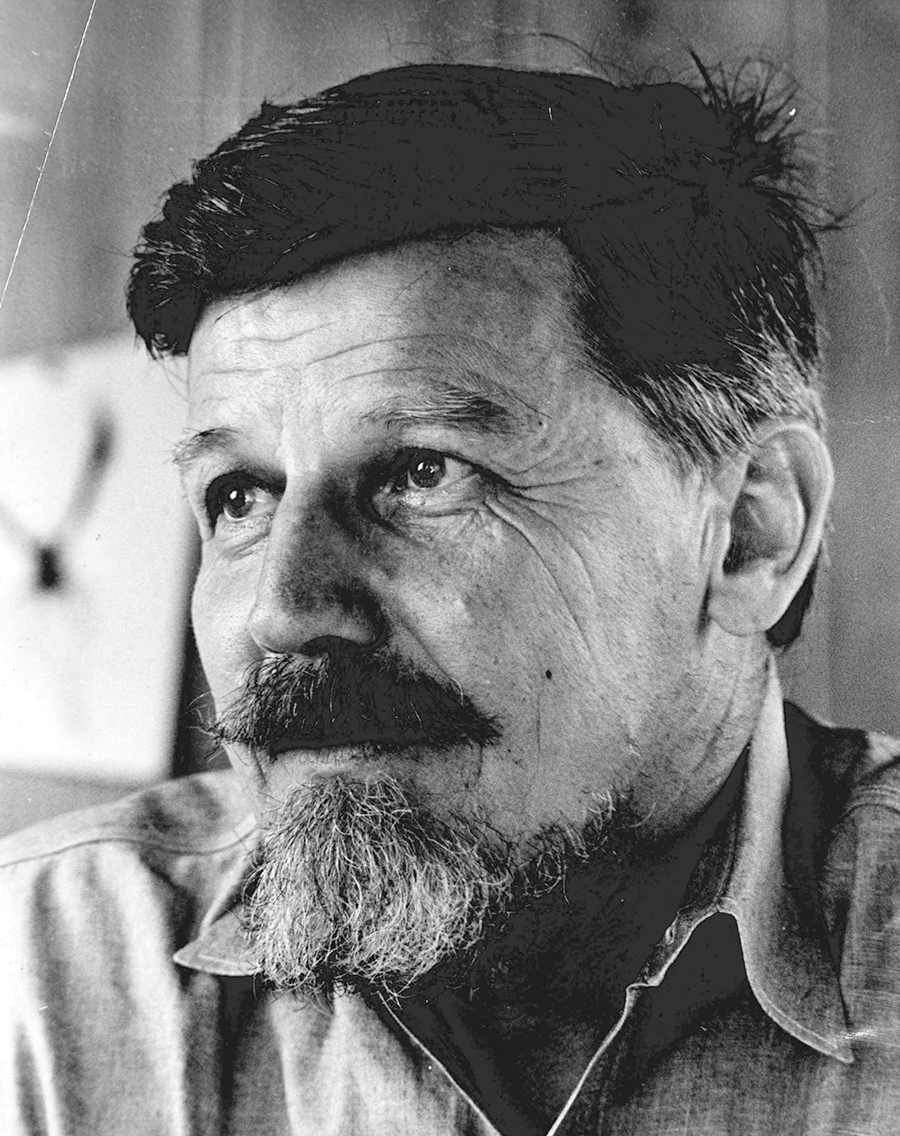

When Southern Pines artist-author-raconteur Glen Rounds was in his mid-90s, he broke his back in a fall and was carted off to the hospital where they immediately removed his gallbladder. A few days later, I visited him and asked, “How are you feeling, Glen?”

“Well,” Rounds said, without cracking a smile, “I feel like those Kansas City girls felt after the Texas cowboys left town: I hurt a little bit all over.”

Rounds was the real deal, an-honest-to-God ring-tailed roarer who authored 103 children’s books. He was also the recipient of the Parents’ Choice Award, six Lewis Carroll Shelf Awards, the New York Times Outstanding Book Award, the Kerlan Award from the University of Minnesota, and the North Carolina Award for Literature.

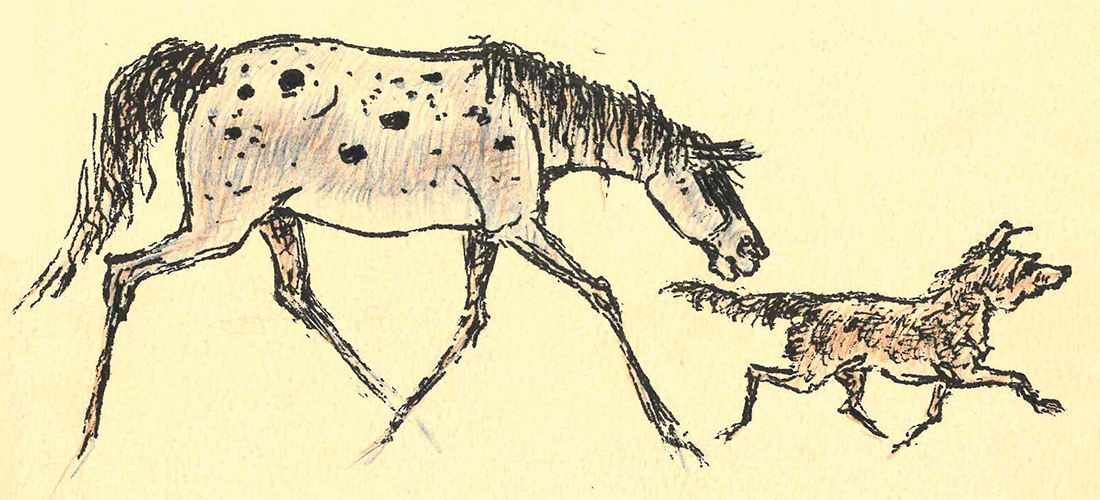

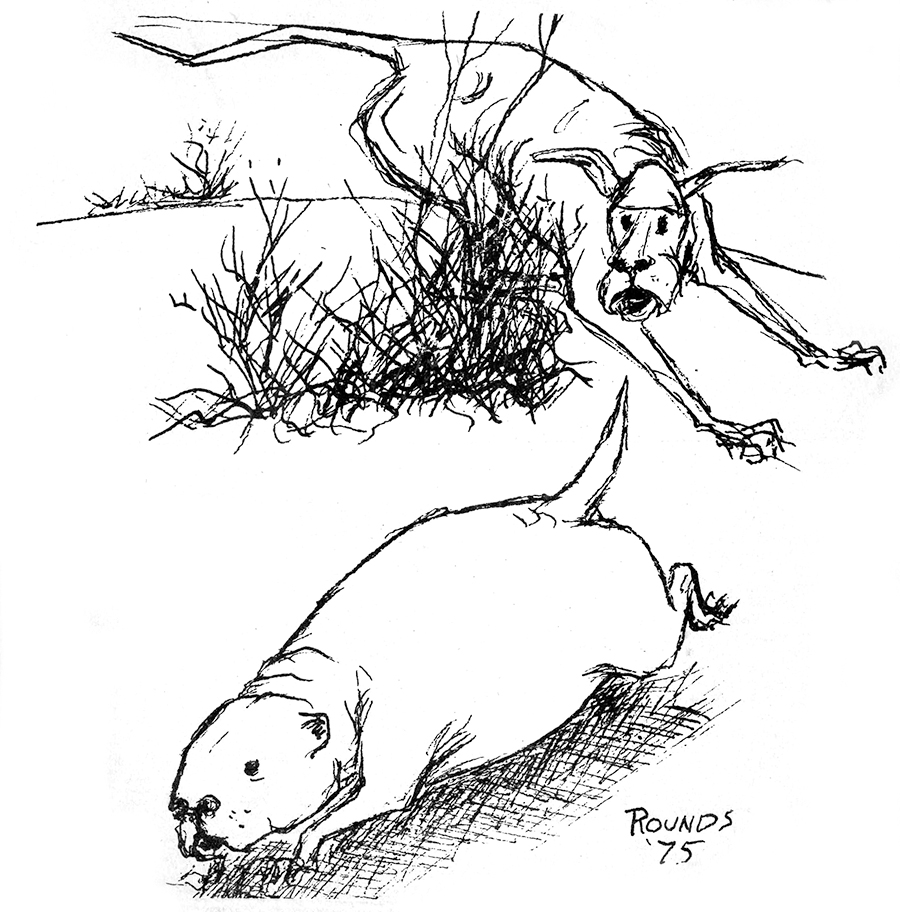

Every Groundhog Day, Rounds’ drawing of a plump, outraged Punxsutawney Phil would grace the front page of The Pilot, and after the spring running of the Stoneybrook Steeplechase, sinewy, intoxicated, loose-jointed partygoers would stagger, waddle and wiggle their way through a Rounds’ drawing, again on the front page. A week or two later an observant reader would notice that the figure in the middle of the Stoneybrook drawing was buck naked. “How’d that get into the paper?” the disgruntled reader and a chagrined editor would want to know.

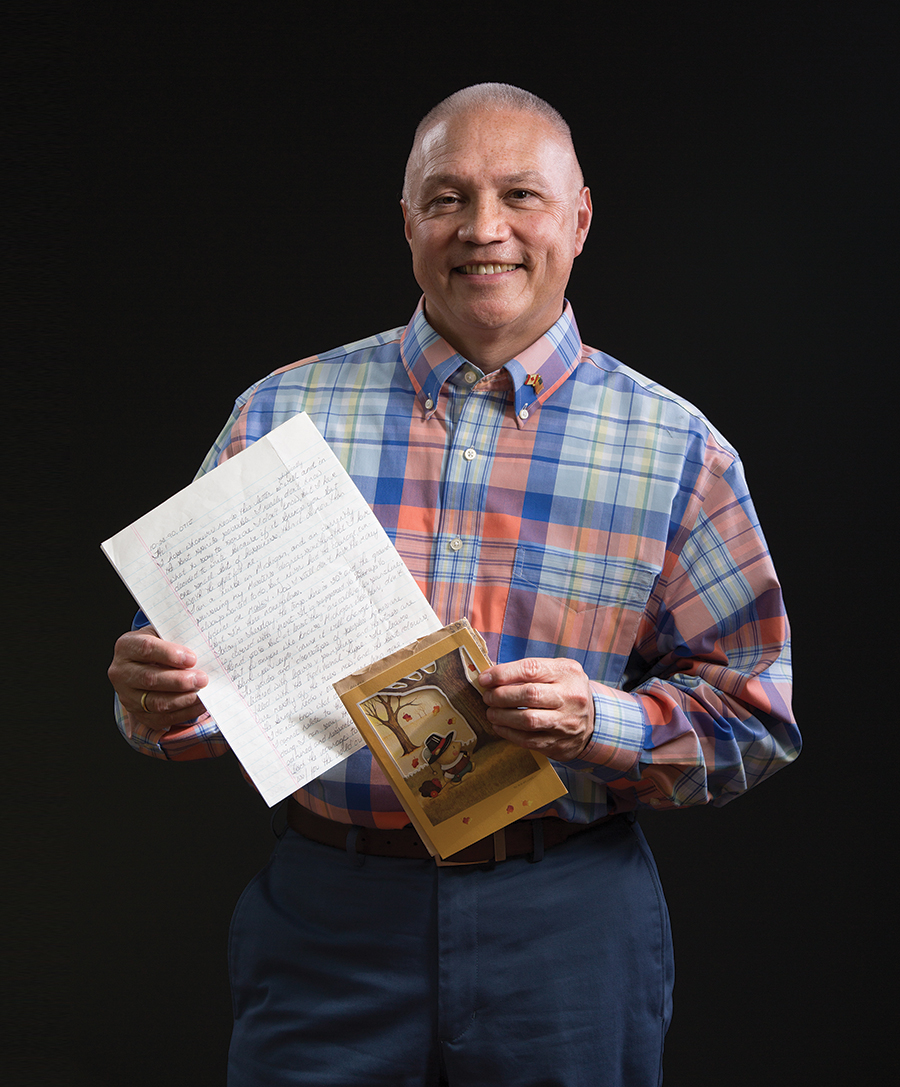

Rounds’ most enduring gifts to the community were the hundreds of drawings he bestowed upon friends and neighbors who were celebrating special occasions. Without warning these minimalist sketches of high-stepping hounds, plump wayward women, and skinny wranglers would appear in mailboxes or stuffed in door jams. Many of them were signed: “The Little Fiery Gizzard Creek Land, Cattle & Hymn Book Co.” A few of Rounds’ drawings survive still on basement walls of businesses in downtown Southern Pines.

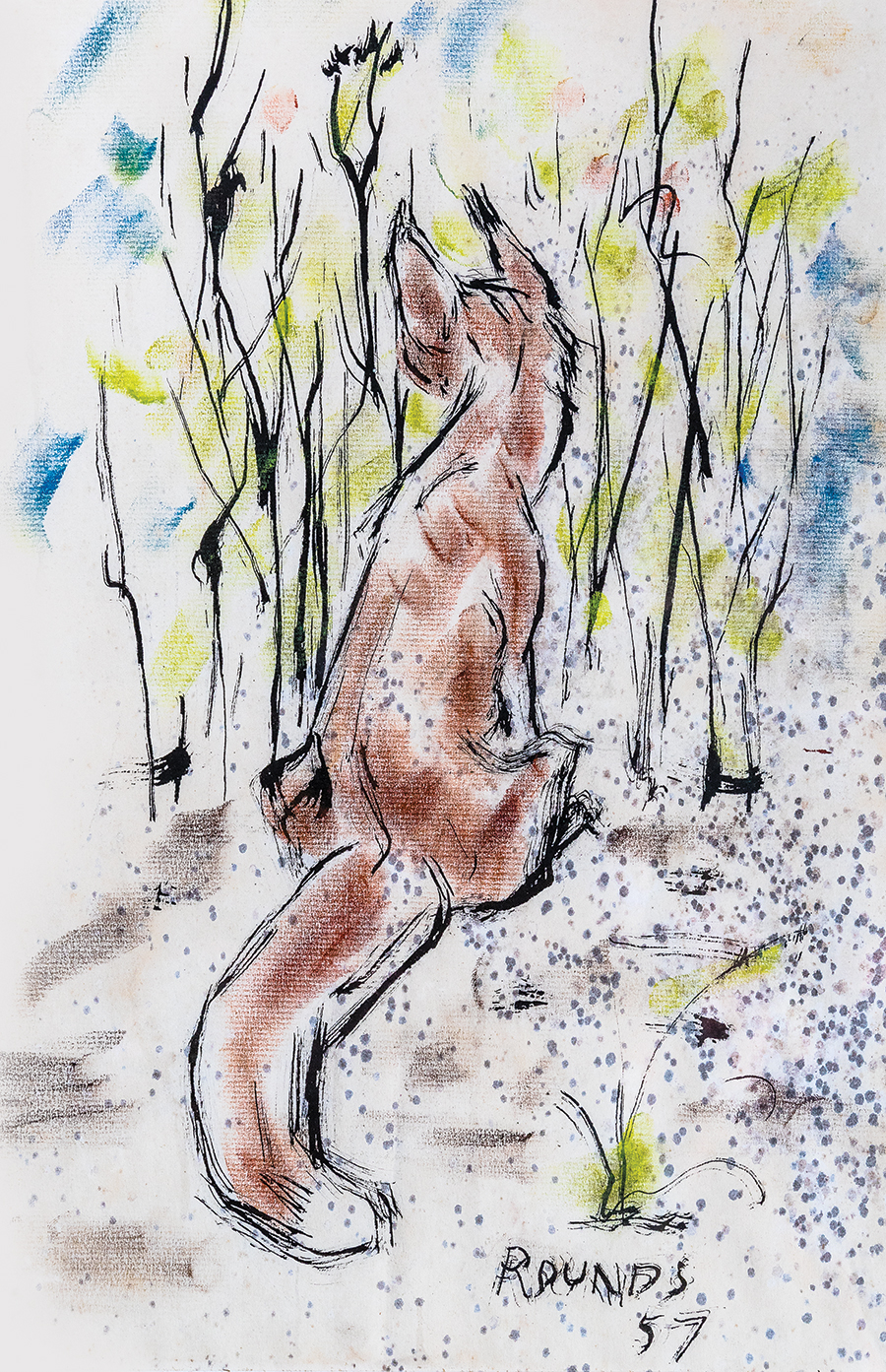

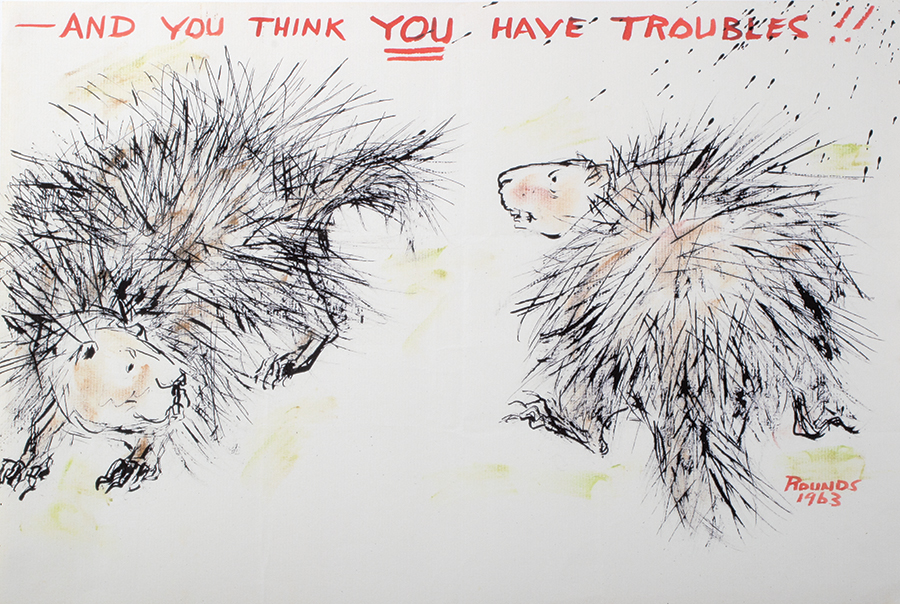

But Rounds’ most ephemeral gift — his most perishable legacy — was storytelling proffered in the moment, narratives that don’t survive in his books or his art. He was a teller of fabulous fictions rife with hyperbole, and for more than 50 years, he buttonholed unsuspecting passersby on Broad Street in Southern Pines with yarns that might last an hour or more. If you were his victim on a warm spring day, one of these outlandish tales would imprint itself, despite numerous twists, turns and lengthy digressions, indelibly in your brain. Years later, a random synaptic connection would propel an injured Easter Bunny, procreating porcupines, or a pack of blue tick hounds vividly into your imagination. Anyone caught up in the telling of one of Rounds’ beguiling tales wished for a videocam to record every word, every facial tick, the subtle smile that graced his craggy face.

Glen Rounds died on September 28, 2002 at the age of 96, but a few recordings of his deftly choreographed tales survive. This charming anti-Easter fable, tentatively entitled “A World Full of Bad Rabbits,” is transcribed from an audiotape I recorded in the late ’80s.

“It all started years ago when somebody mentioned mad March hares. Why would the hares go mad in March? Nobody knew. It might be part of March or into April, this madness with the hares.

“So this old rabbit, he’s an old-timer, sees this paper go blowing across and right down in front of him. It was The Pilot, I think, and he looked down at that thing and all of a sudden he makes some strange noises, jumps about three foot in the air and takes off screaming as much as a rabbit can scream and bumping into sagebrush and cactus and stuff. And the other rabbits who hadn’t been inoculated said, ‘What the hell ails him?’

“The paper said something about Easter being 13 days away, and when the older rabbits saw this, they commenced to have fits. Why did the mention of Easter drive these rabbits into madness? It was always the older ones that went mad. So I researched it and ran it down and what I found it was the old rabbits who’d been through a lot of Easters who were going into this madness.

“Well, it was simple enough! You know yourself that everybody’s going out for the Easter bunny. They have Easter egg hunts in the churches and the President of our United States, if he’s not too busy this year, will have an Easter egg hunt. It’s the Easter bunny laying all these eggs! Now birds go around laying eggs in the most unsuitable places and in that color and this. But rabbits don’t lay eggs unless they’ve been forced to do it.

“Compare the anatomy of a bird with a rabbit, and the bird is especially made to excrete an egg very neatly — and enjoy it! But a rabbit isn’t made like that. Not only are they forced to lay eggs about this size but in various colors. A lot of people see an old rabbit and he looks like hell and they say, ‘He must have been hit by a car.’ Car hell! He just got through laying a dozen Easter eggs. I got drawings of a rabbit that went through two seasons of laying eggs like that, and he can hardly get around.

“After a rabbit has laid an egg, he’s never the same. It does something to their psyches, and it does something to their egg-laying parts. So what we’re trying to do is say, ‘Please, look. Why? If you want Easter eggs in colors, the birds will lay them everywhere. Let the birds do it; they enjoy laying eggs.’ If we don’t do something we’ll end up with a world full of bad rabbits.

“So we need to go to the churches and the President of the United States, well-meaning people, but where the hell they got the idea it was the business of rabbits to lay eggs I don’t know! So I’m forming an organization that says write to your friends, ‘Save the Easter Bunny!’ And then send five cents to me, that’s all a membership costs, and I’ll put up big billboards that say, ‘SAVE THE EASTER BUNNY!’ We need a concerted effort by everybody. See, they have a law about you can’t abuse a dog; it’s cruelty to animals but nobody’s worried about saving the Easter bunny’s butt. Five cents isn’t too much to contribute.”

Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of seven books of poetry and prose. He’s the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press awards.

By Denise Baker

I was a new professor of visual arts at Sandhills Community College when I met Glen Rounds. Glen’s wife Betty, Stephen Smith and I were trying to get Glen to commit to an art exhibit at the college gallery. Glen finally granted us permission with one condition, “The Girl,” that was me, would come over and help him go through his artwork and pick the pieces to be in the show. Every time I knocked at the door of his home on Pennsylvania Avenue, he would yell to Betty: “The Girl is here!”

I was ecstatic. For every piece of Glen’s art I chose, there was a story to be told. Anyone who knew Glen knew he loved to chat.

I don’t think I was prepared for the massive art collection that Glen accumulated over the years. He was the type of artist who sketched on anything, and one of his favorites was the old Pinehurst Gazette, which used to be extremely large. The images were great, but Glen drew on both sides so if you framed one side you buried the other. Glen was a recycler long before it was fashionable and I was captivated by his work, and of course his stories of working with Thomas Hart Benton and rooming with Jackson Pollock who, at the time, was a student of Benton’s.

Glen had flat files of etchings, woodblock prints, lino prints, ink drawings and colorful sketches from all of the children’s books he was most famous for. The early linoleum prints that Glen created had a touch of Thomas Hart Benton with The Grapes of Wrath as subject matter. As a printmaker, I was in heaven and I convinced Glen that the printing plates and woodblocks should be on exhibit with the rest of the art. I am a proud owner of several of Glen’s early prints, and they are among my most prized possessions.

Another thing that Glen did as I was trying to go through the thousands of pieces of art was to stop me and say, “Let me show you something,” and he would proceed to carve delicate images in oversized erasers. The amount of detail that Glen could get in a 1 x 2 inch eraser was magnificent and just watching those enormous rough hands do magic with an X-Acto knife was worth every second of lost curating time. It took me more than nine months to go through his art, but I got to hear amazing stories and watch a master at work. Glen gave me one of his hand-carved erasers with a cowboy and a horse on it, and to this day I love to stamp envelopes with it. The stamp reminds me of the stories he told of the Wild West and heading out with his artist friends.

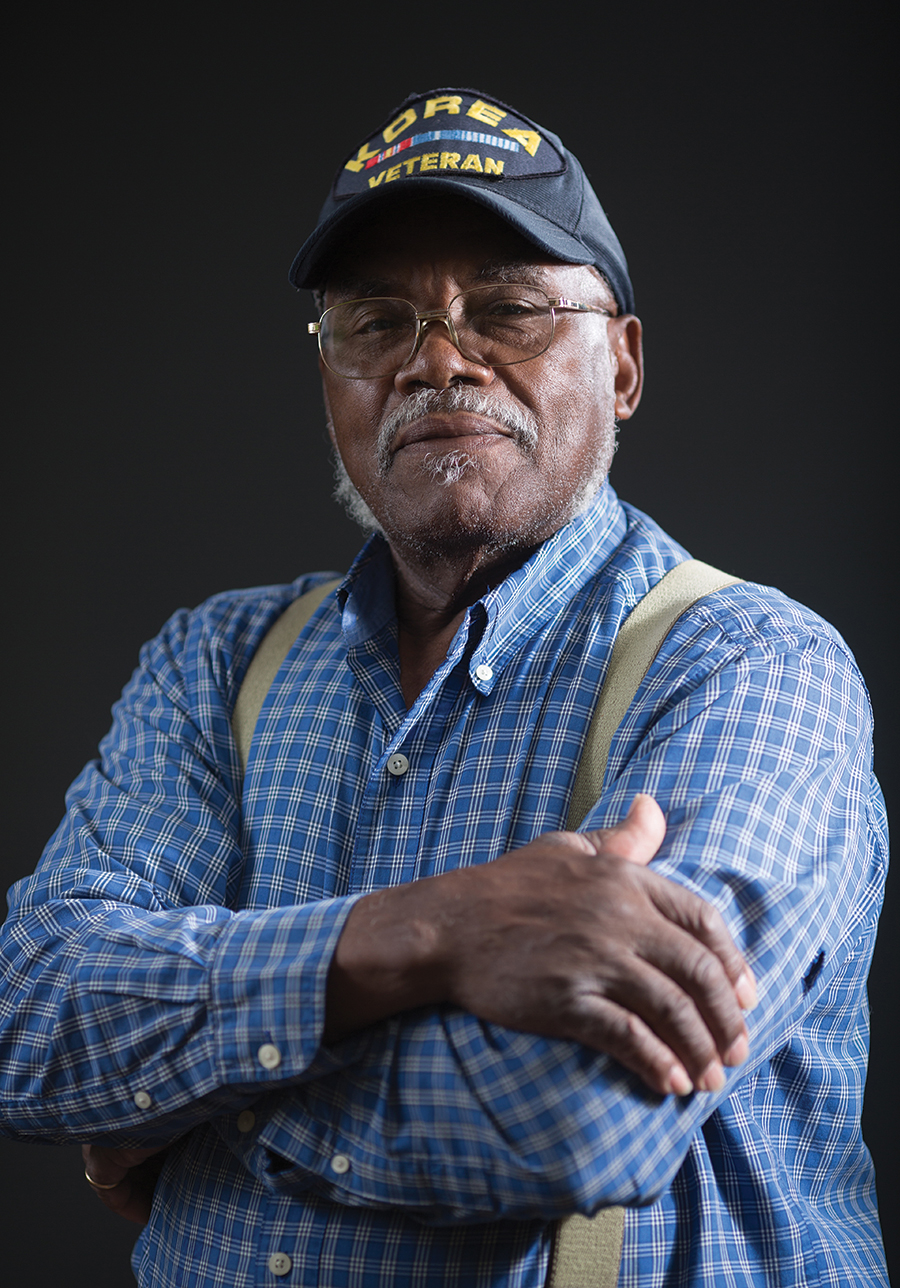

Glen loved to walk to the Southern Pines post office twice a day and talk to everyone he saw along the way. Decked out in his rugged old denim jeans, dapper in his long gray hair and mustache, he was ready to tell a story to anyone who had the time to listen. He was truly the essence of the classic eccentric. I was lucky, I got to listen, watch and absorb everything he offered “The Girl.”

Denise Baker taught visual arts for 34 years before retiring from Sandhills Community College. She’s a printmaker, artist, teacher and an ambassador for Moore County Cultural Arts.

By Dr. Michael Rowland

Glen Rounds and I met as patient and doctor. He’d undergone multiple surgeries and radiation treatments, and I convinced him he needed another surgery. I asked him to follow me to my secretary’s office. I always walked at a very fast clip, and when I reached the office, I expected him to be a good distance behind me. Instead, he ran into my back. At age 77, he’d kept up with me, step for step, and was not even out of breath.

We spent six long hours in a complex surgery — and he recovered uneventfully, living almost 20 more years, during which we enjoyed a close friendship. There were other complicated surgeries, but Glen was amazingly resilient, like the Energizer Bunny, practically bionic.

Our relationship was complex, starting as doctor/patient and evolving until we were like brothers, with the same feeling of trust and love such a bond implies. He’d been around so long, doing so many different things in so many different places with so many wonderful people, and he had a way of making each person he interacted with feel important. He shared parts of himself generously, and he made you feel like family. You’d get busy and miss seeing him for a time but when you next met him it was like you’d seen him just yesterday. He had that very special and unique talent and personality that immediately put you at ease. I always wished I had half his charm.

When Glen learned that I was building a barn on my farm, he proudly told me a story about his uncle, the doctor, who designed and built a barn, with Rounds’ help. Wood was a rare and expensive commodity on the Plains, and the trainload ordered by his uncle was systematically measured, cut, drilled and notched according to his uncle’s directions. The locals continually ridiculed Rounds’ uncle for wasting and destroying all that expensive wood. The next spring a barn raising was held and the pieces of the puzzle came together quickly and precisely, just as his uncle had planned, shaming the neighbors who had mocked him all winter as he sawed and drilled the boards into neat piles.

Eventually, our joint efforts to keep him healthy, sometimes without his full cooperation, brought our friendship to the most personal level. I believe he was grateful for the extra decades we achieved together. We would talk about what we would do when he reached 100, and he would just groan.

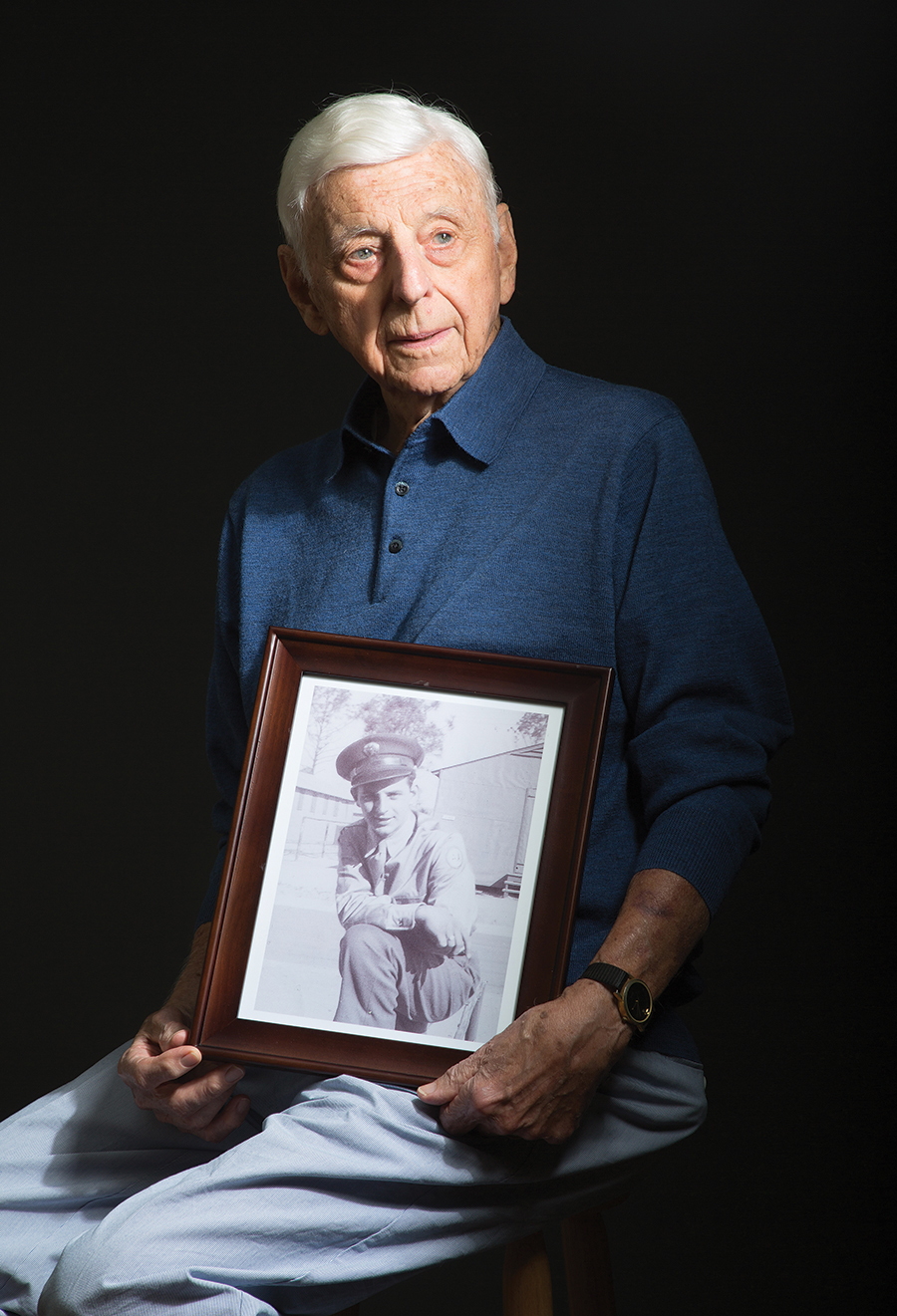

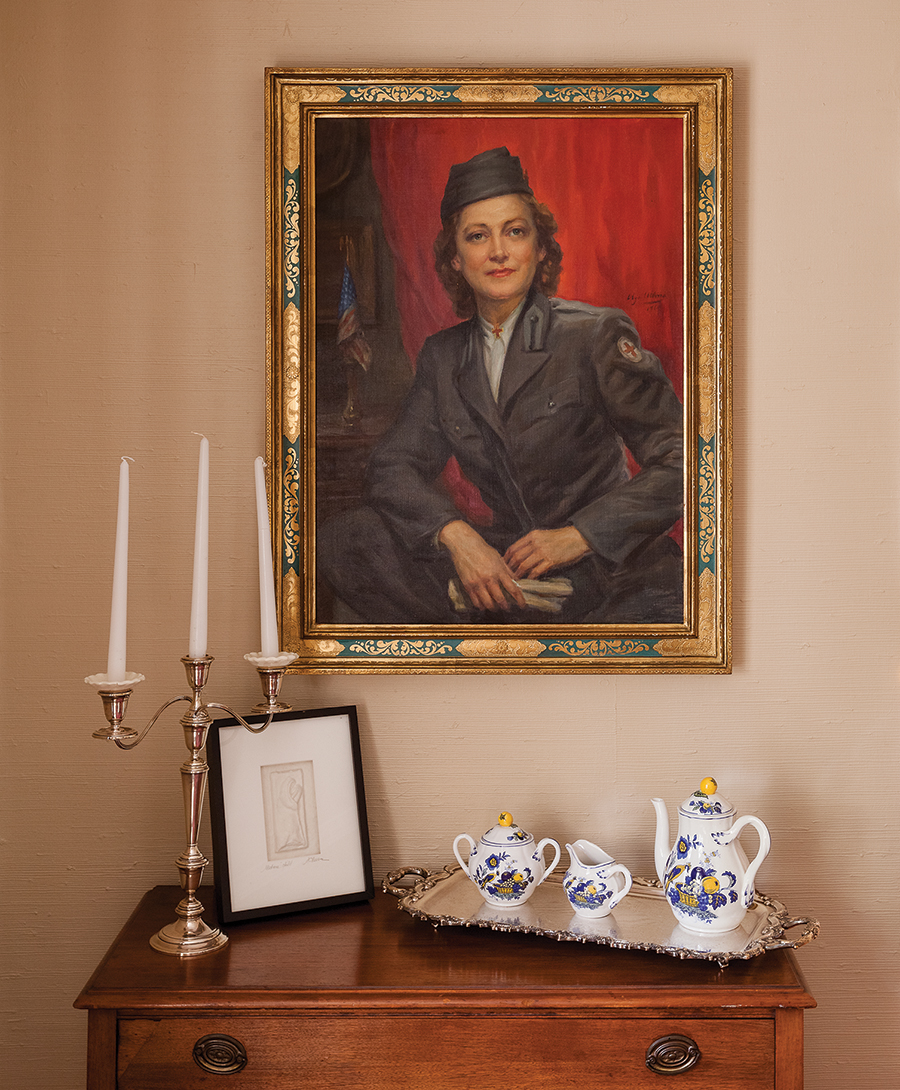

One of the four photos hanging in the dining room where I eat breakfast was taken in early September 2002, just a short time before Glen’s death. He and I talked that summer as my barn with living quarters upstairs was being built. We moved in during August of that year. Glen wanted to take a tour of the new barn because he’d worked so hard with his uncle those many years before. Glen was using a wheelchair and made use of our new lift my parents had me put in so they could get upstairs. Knowing this photo was the last one taken of him makes it extra special to me.

When Glen died, I could not have felt greater loss. And yet he’d said to me on multiple occasions that he was ready for the next destination and weary from the problems and pain his failing body forced him to live with. I wasn’t ready for our relationship to end. There is always guilt a physician feels when a patient dies, yet I have the consolation of his having lived a long and productive life that brought so much joy to so many. I still miss him dearly. His picture, looking like Paladin (Have Gun Will Travel), is in front of me every morning. I still feel he is a part of my life since I can look up and see him smiling down on our dining room, one of the last places he visited before leaving us for good. PS

Michael Rowland is an organic grass-fed beef farmer, retired general surgeon, and nutrition lecturer.