Taking a moment to remember

By Jim Moriarty • Photographs by Tim Sayer

It is the most American of holidays, celebrated with a parade of giant cartoon inflatables through the heart of one of America’s greatest cities, football games in some of America’s greatest stadiums, and food that draws its flavor from roots sunk deep into who we are. On this Thanksgiving, like so many before it, there will be friends and neighbors hunkered down in dangerous places in corners of the globe where the niceties of the holiday are meager, and the delights it holds are distant. Left behind are their families who want nothing more than the next Thanksgiving together. While we sit in our homes surrounded by too much food at a table where there can never be too much family or too many friends, be thankful for those who do for us now as those on the following pages — who represent the many — have already done. Every experience was singular. On sea or on land, forward or in the rear, they had two things in common. They weren’t where they wanted to be. They were where they needed to be.

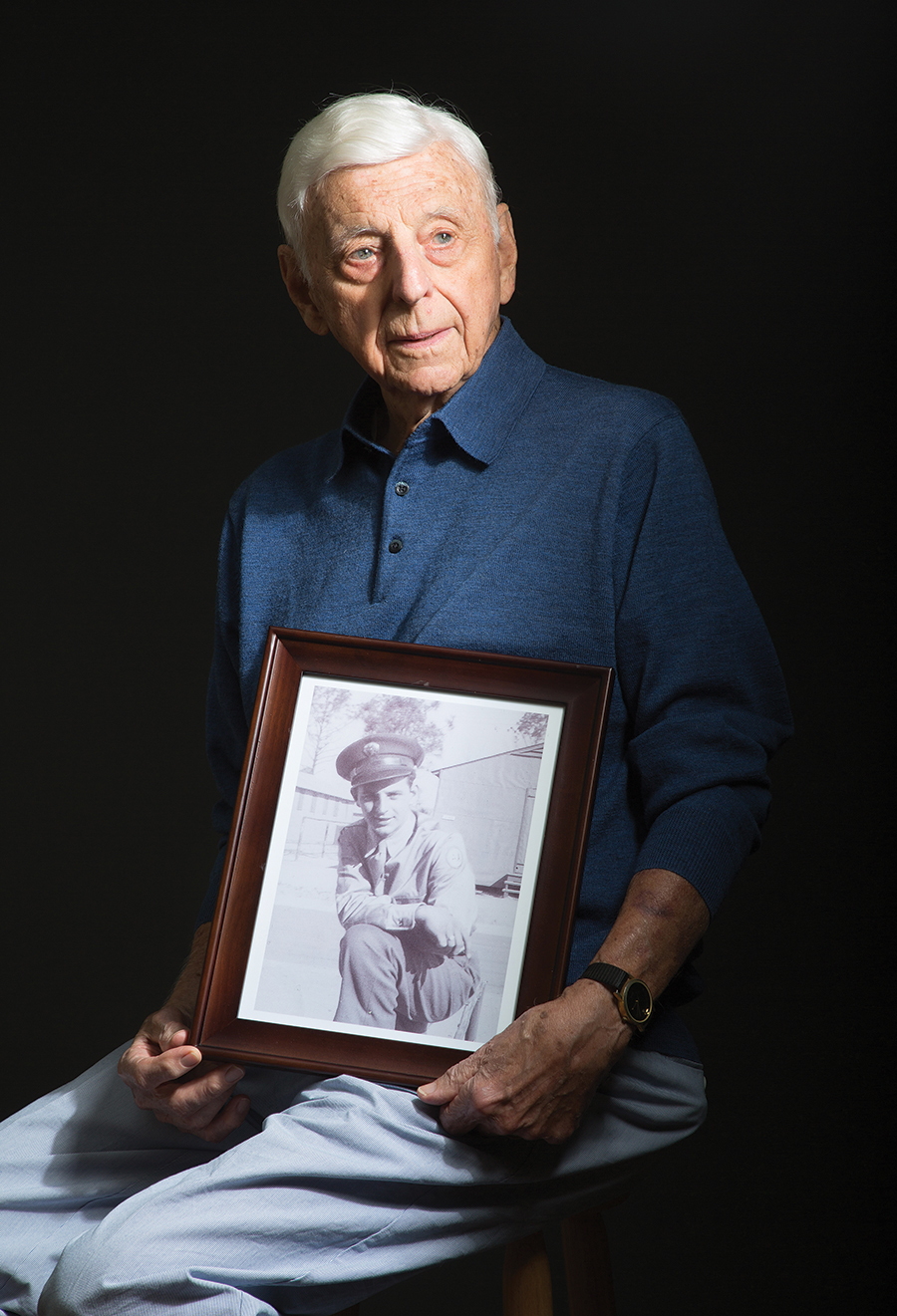

World War II

Len Grasso was drafted in March of 1943. He was 18 years old. A member of the Liberty Bell Battalion — “Our number was 776,” he says — Grasso spent one Thanksgiving in basic training and the next two making his way across France and Germany.

“We were out on forward airstrips. They were just metal strips that they laid down in a level area. We had P-47s, P-51 Mustangs and P-38s that were called the Black Widow.” Grasso manned the guns surrounding the airfield. At Thanksgiving a truck came around to collect the men.

“We’d all hop in that truck and they’d take us back two or three miles and there’s this big mess tent. We had to be there at a certain time because when we got through another group would come in and another group after that. This was one of the hottest meals we were ever going to get. We had the mess kit. They piled on the turkey and the dressing and gravy, the potatoes. They would overflow and they’d throw the dessert on there. Everything was all mixed up.

“I went into that tent as a 19-year-old boy and came out a 19-year-old man. I saw these people — DPs, displaced persons — that had nothing. I’ll never forget. I noticed a family of four. A husband and wife and two children. They were digging into the garbage pail. If I’d only known who they were, I would have given them my meal because I was hungry but they were starving. That’s the saddest thing I remember about Thanksgiving.”

World War II

Eli Jaksic was drafted in July of 1943 at the age of 18. He was still a student at Emerson High School in Gary, Indiana. When he got out of the service in ’46, he returned to get his diploma, before going on to Drake University, where he was a 5-7, 130-pound forward on the basketball team. Today he’s got more jokes than Bob Hope. In fact, he’s probably got Bob Hope’s jokes.

Jaksic was a machinist’s mate third class. He spent two Thanksgivings on the Pacific Ocean, one aboard the USS Furse, a gasoline tanker, and another on the USS Dawn, a Gearing-class destroyer, on occupation duty. “They had good fresh meals,” he says. “Happy Thanksgiving and a prayer and all that sort of stuff.”

In between he spent Thanksgiving with the Seabees in Gamadodo, Milne Bay, New Guinea. “When we were going to invade the Philippines, I was on this gasoline tanker. It was built in 1923 and it had an old reciprocating engine,” he says. “We filled up the tank with millions of gallons of 100 octane gasoline. We were so slow we had to go out three days in advance and the convoy caught up with us. We were lucky we didn’t get bombed or torpedoed.”

As a 9-year-old boy, Jaksic was placed in an Indiana orphanage following the death of his mother. His father wasn’t able to put the family back together until three years later, when he found work in the Gary steel mills during the Great Depression. All of which made Thanksgiving of 1946, Eli’s first stateside after the war, extra special.

“Real beautiful,” he says. “We had somebody come in to make dinner. A friend of my father’s. I’ll always remember that.”

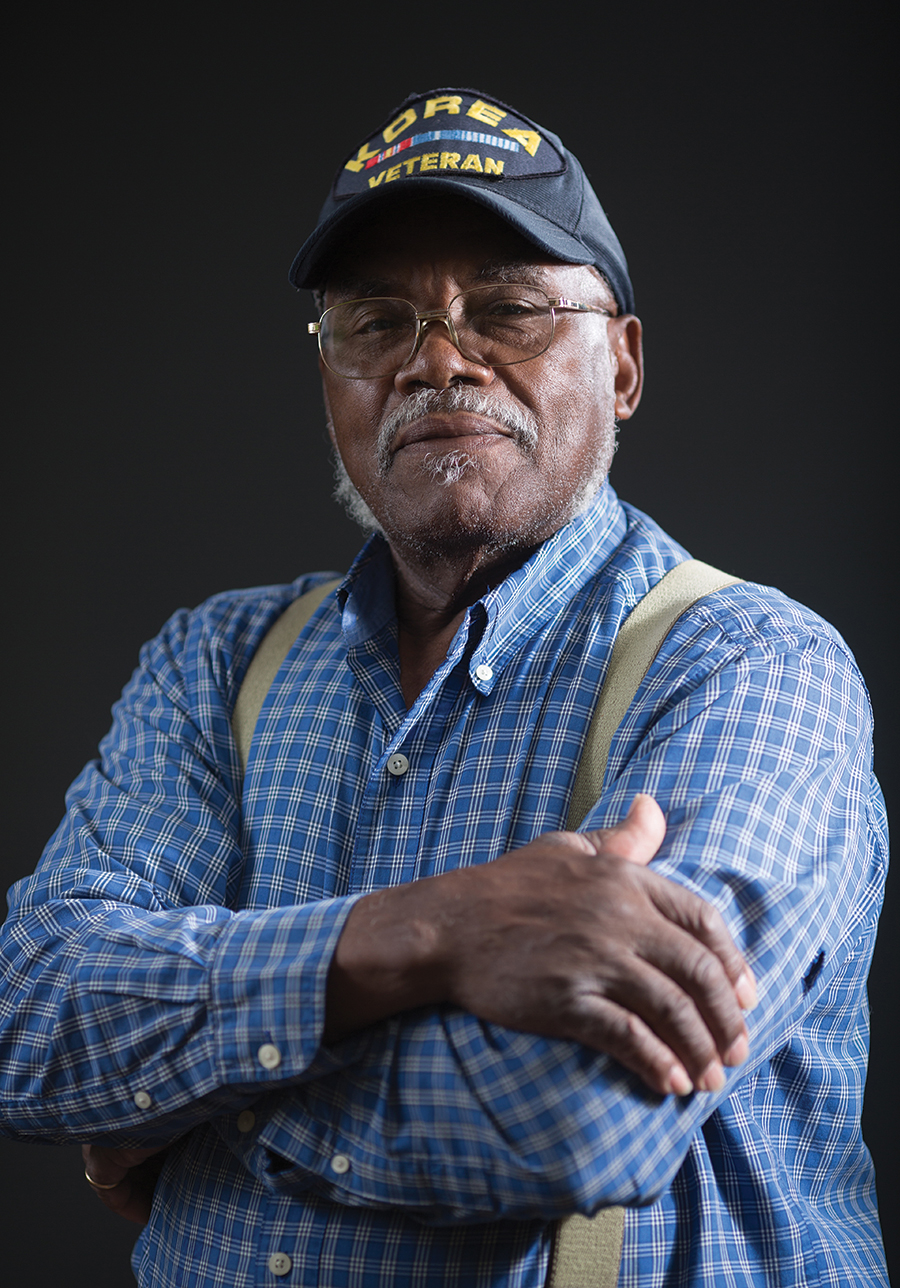

Korea

Halbert Kearns was drafted in 1952. He was in the 7th Division, Charlie Company, the third platoon, manning an outpost protecting Pork Chop Hill, the site of a pair of battles that took place during the spring and summer of ’53 while the armistice negotiations were going on in Panmunjom.

“My company was in the rotating cycle, relieving different platoons,” says Kearns, who was born in Hoke County but moved to Pinehurst when he was 12 years old.

Thanksgiving was just another Thursday. “You didn’t have like Thanksgiving dinners or Christmas dinners. We just had C-rations because we were on outpost,” he says. “A lot of times you didn’t even know what day of the week it was. Sunday was about the only time you realized it was a Sunday because sometimes the chaplain would come out and have a service. Some Sundays we weren’t fortunate enough to have that.”

Kearns got out of the service in ’55 and worked at the Pinehurst Harness Track for 32 years, traveling up and down the East Coast, doing “whatever came to hand.”

Vietnam

Gene Schoenfelder was a petty officer second class who entered the Navy in 1970 and served on three nuclear submarines, the USS Francis Scott Key and the USS George Washington Carver (a pair of ballistic missile submarines), and a fast attack submarine, the USS Tenosa. “All the boats I was on are decommissioned now,” says Schoenfelder, who spent most of his working life in construction management, including work on the World Trade Center.

Each sub had two crews, a Gold and a Blue. “My rotation was gone for Thanksgiving and Christmas. That was the rotation of the Blue Crew,” he says. “You submerged on Day 1. The longest I was under water was 132 days, I think it was. Because I was in navigation, when we’d come up to periscope depth at night, at least every now and then I’d get to go on the periscope and look at the stars but, basically, you were under water.

“The thing about submarine service is they have the best cooks of, I think, any service. The Thanksgiving dinner on the Key was just fantastic, everything you could want except, of course, you weren’t at home. I remember watching them loading these big, beautiful Butterball turkeys.”

It wasn’t always smooth sailing. “On the Tenosa we were out on patrol. The cooks were making some turkeys for the crew. Everybody is kind of grumbling because you could smell that turkey and everybody was getting hungrier and hungrier and grumpier and grumpier.” Then, the boat executed the American version of a Crazy Ivan (fans of The Hunt for Red October will recognize the term) without warning. “The guys are in there cooking and all of a sudden they take a roll and out comes the turkeys, sliding across the floor, grease all over the place,” says Schoenfelder. “The cook is furious. Thanksgiving dinner’s now gone. We had turkey and cranberry sauce sandwiches.”

Vietnam

Ted Mataxis likes to say he failed retirement. After a 31-year career in the Army, he spent another 20 years in education, 19 working for Moore County Schools. Unable to rest on his Harleys (he owns two), he still commutes to Fort Bragg to work in the history office. In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s he spent three Thanksgivings in Vietnam.

“The first one was when I was with the 101st. All we had to do for that one was move to a landing zone where they could come in and pick us up, take us back to the rear, which was a firebase in the mountains, and then redeploy us to another area afterwards. That one wasn’t too painful.

“My last Thanksgiving there I was at a border Ranger camp, Polei Kleng Camp. Elevation was just about 2,000 feet. We had a 3,500-foot airstrip which was made out of perforated steel and we had a little old triangular French fort. There were only two Americans, we had three-man teams but at that particular time we only had two of the three slots filled. I had a battalion of Montagnards with me and I’ve got a village of Montagnard families. We got word that we had to accept a Thanksgiving meal that was being flown around to all the various camps. If you’re sitting in Saigon, say, a general looking at his map says, ‘These places all have airstrips, here’s what we need to do. I want every camp out there to get a meal.’ Yes, we had a strip but anytime anyone was coming in, they were subject to being fired up. To accept them we had to deploy a battalion worth of my soldiers so that myself and my NCO could have hot turkey.”

It was a Thanksgiving dinner he’d have been content to do without.

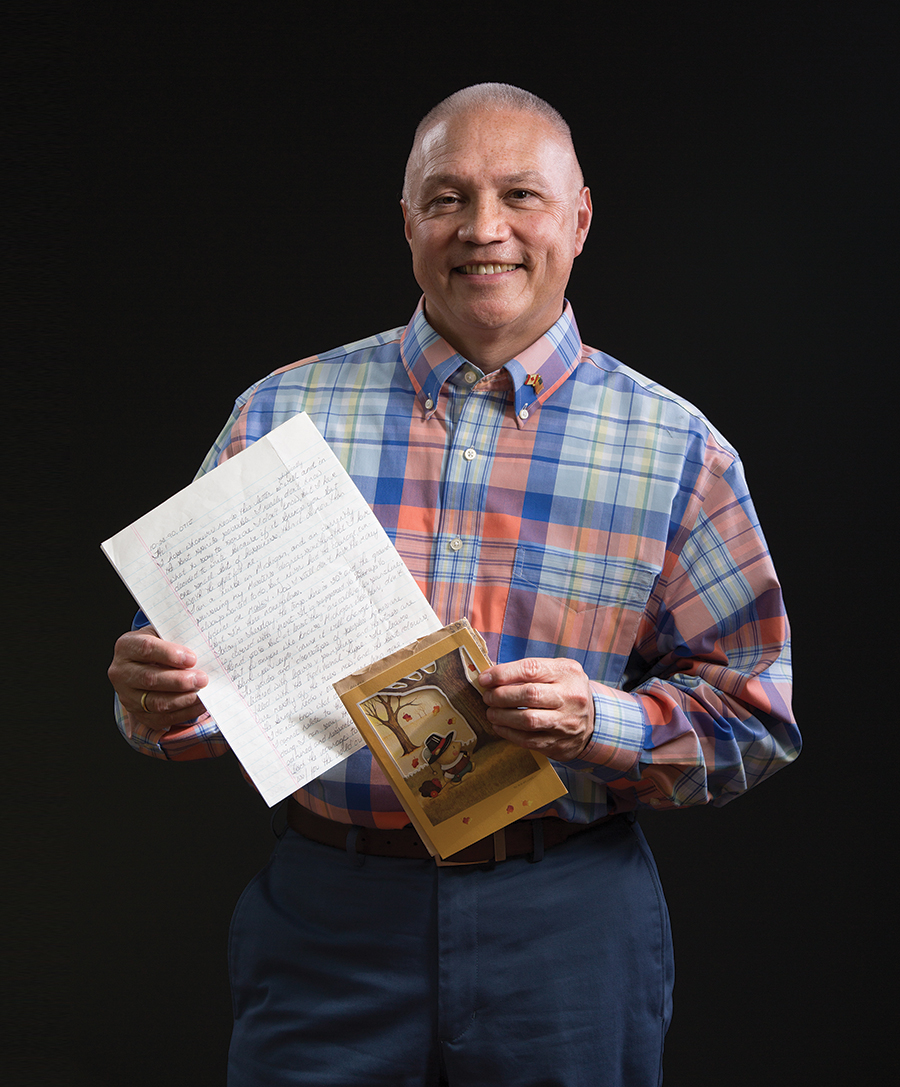

Bosnia / Iraq

Lloyd Navarro was deployed for 14 Thanksgivings over a 26-year career, including one in bombed-out Zetra Stadium in Sarajevo. “It truly was an international force,” says Navarro. “We had Canadians. United Kingdom. Members of the Turkish force. When Thanksgiving came up it was kind of foreign to them how much emphasis we put on it. We wanted to show the multi-national force what Thanksgiving meant to us.”

Different U.S. units did different things. One dressed entirely as Pilgrims. “Our unit did the Remembrance table or the Missing Man table. It’s to commemorate fallen comrades. We literally had 10 soldiers lined up. Two would bring in the table. One would bring in the chair. Then there would be a plate set with a vase and one single rose. Each item represented something. There’s some salt on the plate. A lemon. A white tablecloth. There were interpreters who were explaining exactly what was going on. It was kind of educational but it made us all come together. It wasn’t going to be just a meal.”

That, however, wasn’t his most memorable Thanksgiving away from home. During Desert Storm/Desert Shield, Lloyd’s wife, Leslie, was an unattached graduate student in Michigan studying nursing. The local newspaper suggested people write letters to “any” soldier. “She wrote a letter and along with it was a Thanksgiving card,” Lloyd says. “Her letter came to my unit. I had a rule, if you picked a letter out and opened it, you had to reply to that individual. One of my young soldiers picked her letter.” In it, Leslie explained a little about who she was.

“To this day I can see his face,” Lloyd says. “He brought her letter to me and he says, ‘Sir, I know your rule and everything but I don’t have anything in common with her. She’s about your speed.’”

They’ve been married 25 years. He still has the Thanksgiving card.

Iraq / Kuwait

Catherine “Cat” Jones was a communications officer who left the Army in 2015 with the rank of first lieutenant. “I was never in any operating area where anybody was shooting. There were never IEDs. No explosives. I was like an air traffic controller for convoys. You remember when we left Iraq the first time, back in 2011, my unit had to manage all of the physical assets and people getting out,” she says.

Thanksgiving was at Camp Arifjan in Kuwait. “The base itself had a lot of people, but there were only four of us in my battalion, three dudes and me. OK, it’s Thanksgiving. We’re not home. We all miss our families. I tell them, you guys sleep in today, go to the gym, go play basketball. I’ll get there at 7 and take care of everything until noon. Then you guys figure out who’s going to come in. There’s not a whole lot going on. Everything’s kind of low amp at that point. They said, ‘OK, ma’am.’

“They all get there at 6:30 to make sure they got in before I did. ‘Ma’am, we’re not at home. We’re not with our families. At least if we’re here, we’re with our deployed family.’ OK, touché,” she says.

“We sat around and talked about all the foods that we missed that we would normally have. Pumpkin pie. Somebody’s favorite turkey. Maldonado had three stepdaughters — it was his lot in life to be surrounded by beautiful women. Rogers had twin boys. We were just our own little cluster of goofiness.”

Afghanistan

Jeb Phillips was part of a Special Operations support battalion in Afghanistan in 2003. “We deployed on a surge, believe or not. It was up in Asadabad. It would remind you of Shangri-La with the terraces, agrarian fields. Close to Pakistan. Little one road network up into it from Jalalabad. It was incredibly beautiful. At that time you felt you were on the edge of the empire, so to speak.

“Working out of Bagram (Air Base) we flew in at night. It was a pretty narrow area. It probably wasn’t much bigger than this block. They had room for one Chinook at that time, maybe two Blackhawks. Looked like it was an old fort which most of the U.S. forces were occupying. A Special Forces company, some soldiers from 10th Mountain. Rangers were using it for a bed down facility. Had some interagency people and some Afghans working with the interagency people. Everybody was doing their own little stuff.”

The only kitchen was a cement slab with walls around it and a propane gas hookup.

“I ended up going back to Bagram to pick up some parts and things for some generators. It was getting close to Thanksgiving. I talked to a few of the cooks from all these different elements about doing a Thanksgiving dinner. About four days later I got on a Chinook late at night and I had parts, ammunition, some documents and a lot of turkey breasts in mermite cans (insulated containers). The rest of the Chinook was full of Rangers,” says Phillips.

“We flew back and started preparing for Thanksgiving dinner. Told the elements what we were doing. All the officers were going to serve. The cooks were awesome. We had collards, yams and pies, shipped up by other means. At that time we were able to have a satellite so we had Armed Forces Network. One big huge screen. Watched a football game. We were 13 1/2 hours ahead. It’s a half an hour because they’re on funky time. It might have been a college game from the day before. One guy who volunteered to cook wasn’t necessarily a cook by trade. Even to this day, the greens, I don’t know which one of the cooks did it. It was the best greens we ever had. It was tight in that little room. People were just stuffed. You saw nothing but smiles on people’s face. We got in there and pulled together. It was amazing. It was ours.” PS