Songs of Home

The Steep Canyon Rangers celebrate the music of the Old North State

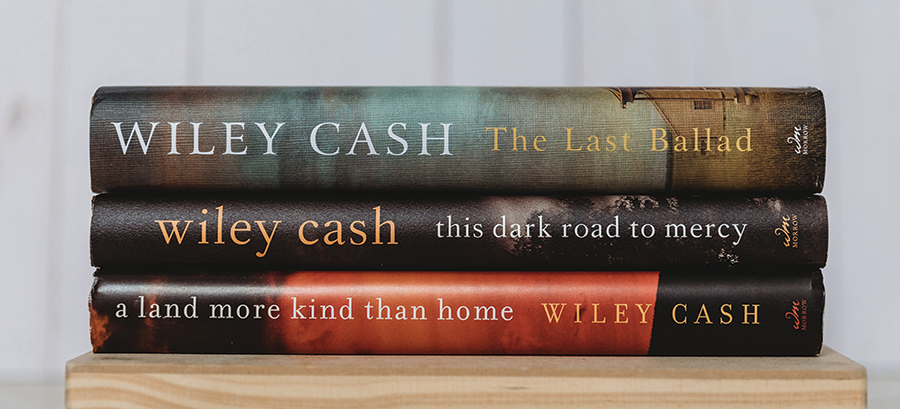

By Wiley Cash • Photographs by Mallory Cash

What do you do after spending several weeks playing sold-out shows across Australia, some of them with Steve Martin and Martin Short? If you are the Steep Canyon Rangers, you come back to North Carolina and play a lunchtime show inside a strip-mall record store in Raleigh. If you are the Steep Canyon Rangers you even carry your own equipment through the front door and snake your way through the crowd on the way to the stage.

There were no crowds when I arrived nearly an hour or so before the noon show on a chilly Wednesday in early December. The Steep Canyon Rangers had just released their latest album, North Carolina Songbook, which they had recorded live at MerleFest in April. The album is a celebration of North Carolina music, featuring the band’s renditions of the work of some of North Carolina’s most foundational voices, including Thelonious Monk, Doc Watson, Elizabeth Cotton and James Taylor. The album was released on the Friday after Thanksgiving, a day that many music lovers have come to revere as National Record Store Day Black Friday. In support of the album, the Rangers had decided to play record stores, starting with School Kids Records in Raleigh.

If you want to feel uncool, I invite you to visit an independent record store that sits a stone’s throw from a university campus.

“VIPs only down front,” says the record store manager from behind the bar. I call it a bar because while it is a counter where you can pay for records and merchandise, it is also a bar in that beer is served from behind it.

“I’m friends with the band,” I say. He knits his brows as if he has heard this hundreds of times over the years from lame dads like me. But it is the truth. I went to college with mandolin player Mike Guggino, and I have written about the band and gotten to know them over the years.

I decide to try another tack. “I’m with the media,” I say, which is also true. After all, you are right now reading the media story I wrote, but this was not enough for the manager.

“You have to purchase an album to be a VIP,” he says.

“That’s it?” I ask. “I was going to do that anyway.”

“Great,” he says, not smiling. “You can be a VIP.”

As the clock crawls closer to noon, the store begins to fill to capacity with a mixed crowd that ranges from college students to retirees. Someone has ordered pizza. Beers are being passed from the bar back through the crowd.

“Do a lot of bands play here?” a middle-aged woman asks the manager.

“A couple times a month,” he says. He looks around. “But nothing like this.”

I hear someone say my name, and I turn to find Graham Sharp, one of the band’s vocalists, carrying his guitar case and pushing through the crowd. I say hello to him and pray that the record store manager has seen us greet one another by name.

The rest of the band streams in behind Sharp, each of them carrying an assortment of instruments. The band takes the small stage, nearly filling it. The room is warm and pleasant; everyone clearly happy to be out of the office or skipping class in favor of live music from one of North Carolina’s most famous bands.

“Hey, y’all,” Sharp says to the audience. “These are songs we recorded at MerleFest.” The crowd cheers at the mention of the iconic festival. “But we haven’t played them since April.”

“We relearned them on the way here,” says lead vocalist Woody Platt to the audience’s laughter. And then the band is off into a rollicking version of Charlie Poole’s “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down,” Platt’s rich baritone playing a wonderful historical opposite to Poole’s higher pitch.

The event soon takes on the feel of a college keg party, a feel that is intimately familiar to the Steep Canyon Rangers. The band was co-founded by Sharp and Platt at UNC-Chapel Hill in the late ’90s, when both were undergraduates. They released their first album in 2001, and they have released 13 albums since then, a few in collaboration with Steve Martin.

“This new album is a homecoming for us,” Platt later tells the audience. “We released our first record with Yep Roc Records, and that’s who’s just released North Carolina Songbook.”

And what a homecoming. The album is not only a celebration of famous North Carolina musicians and their music; it is also a testament to the Steep Canyon Rangers’ ability to blend and bend genres and styles while making a cover song seem like their own.

The band moves through gorgeous covers of Thelonious Monk’s “Blue Monk,” Tommy Jerrell’s “Drunkard’s Hiccups,” Ola Belle Reed’s “I’ve Endured,” Elizabeth Cotton’s “Shake Sugaree,” closing out the set with the state’s beloved James Taylor’s “Sweet Baby James,” sung by bassist Barrett Smith, a longtime friend of the band who is the newest addition.

At the close of the show, Platt sets down his guitar and tells the audience that the band will hang around for a little “shake and howdy,” but they have to get over to Chapel Hill for a mic check. They are singing the national anthem at the Dean Dome before tonight’s Tar Heels game against Ohio State. A homecoming indeed, but while so much has changed for the Steep Canyon Rangers, shows like the one at the record store prove that so little about them has. PS

Wiley Cash lives in Wilmington with his wife and their two daughters. His latest novel, The Last Ballad, is available wherever books are sold.