From its brutal beginning as a reformatory for “wayward” girls, Samarcand Manor’s transformation into a state-of-the-art law enforcement training center strives to live down its checkered 100-year history

By Bill Case

The dorm rooms are decorated with ancient mattresses and discarded clothing, occupied only by a ghostly albino cat that brushes my pants leg. You could almost hear the paint peeling from the walls. “If ever a place is haunted, it’s this one,” I muttered while traipsing through the derelict corridors of Gardner Hall, slated for the wrecking ball, at Samarcand Manor, North Carolina’s now closed reformatory for delinquent girls. More than a generation ago the dormitory housed “wayward” teenagers in Eagle Springs at what was once known as the Home and Industrial School for Girls — referred to throughout its century-old history simply as Samarcand Manor. My guide, Richard Jordan, the head man at Samarcand Training Academy (the state’s occupant of the campus since 2015), pointed to a large chamber of the eerie building. “They used this as the infirmary for girls recovering from the surgeries,” he confided. Over a decade ago the North Carolina General Assembly admitted that the surgeries Jordan referred to should never have occurred.

Gardner Hall’s forsaken appearance stands in stark contrast to the current spic-and-span look of most of the campus buildings, all geared toward providing the ideal environment for instructing and training North Carolina’s law enforcement and corrections personnel. Tucked away in the pinewoods, Samarcand Training Academy is state-of-the-art. But even a century after its founding in 1918, Samarcand Manor remains a subject of controversy, little of which is gleanable from the historic marker alongside N.C. 211, 3 miles north of what is now the academy. It is not the simplest of histories to unravel. State law protecting the identity of juvenile offenders hinders obtaining first-hand accounts, and it wasn’t exactly the kind of institution to have a thriving alumni association. Old newspaper articles raved about the place, but two recent books, Bad Girls at Samarcand, by Karen L. Zipf, and The Wayward Girls of Samarcand, by Melton McLaurin and Anne Russell, paint a far less flattering picture.

The use of the 230-acre main campus for educational purposes predates even Samarcand Manor’s existence. In 1914, noted educator Charles Henderson opened the Marienfield Open-Air School for Boys on the property. In the early 20th century, a near plague of tuberculosis had swept the country. Educators like Henderson believed that exposure to fresh air could ward off the disease, so his school held classes outdoors. The advent of World War I resulted in such a significant loss of manpower that Marienfield was forced to shut its nonexistent doors.

It was a Presbyterian minister from Charlotte and a North Carolina women’s club leader who lit the fuse that led to Samarcand Manor. In 1914, Rev. A.A. McGeachy began receiving statewide attention for his powerful sermons urging parishioners to perform “good works” in service of the Lord. Focusing his exhortations on the plight of those he referred to as “fallen women, seduced by the streets into lives led in sin,” McGeachy preached that good Christians should be concerned about the rehabilitation of female prostitutes and other young women of loose morals — the victims of sexual debasement at the hands of devious male ne’er-do-wells. McGeachy suggested they could be redeemed in a “reformatory for fallen women” and forcefully advocated that the state establish one.

In 1917, a print of McGeachy’s sermon found its way to Hope Summerell Chamberlain, a tireless advocate for the North Carolina Federation of Women’s Clubs. Galvanized by McGeachy’s missionary message, Chamberlain and NCFWC’s president, Kate Burr Johnson, began beating the drum at the legislature in Raleigh for a bill to create the “State Home and Industrial School for Girls and Women.” The vacated and secluded Marienfield campus emerged as the ideal location.

Some lawmakers expressed reservations. Were both young girls and adult prostitutes to be housed at the same facility? Apparently so, at least at first. Would female felons be mixing with girls who had committed minor violations? The proponents of the bill thought not, but there was nothing to prevent this. Wouldn’t it be better to attend to these females, particularly younger ones, in or near their home counties? The advocates argued that the state could more uniformly deal with the girls and women in a single institution. How long could the “State Home” keep girls in custody? The length of a girl’s incarceration, up to three years, would be left to the sole discretion of the reformatory’s Board of Managers. So much for due process.

The collective pressure from the NCFWC’s member clubs and other civic groups successfully strong-armed the bill through the legislature, eventually passing it with nary a dissenting vote. Samarcand Manor would house only white women and girls. The legislature gave no thought to funding a reformatory dedicated to the rehabilitation of “wayward” black girls until 1925.

In short order, dormitories, school and administration buildings, a chapel and a home for the new superintendent were under construction. The five-person board of managers hired Agnes MacNaughton as Samarcand’s first superintendent. Before long, close to 200 young females inhabited the campus. According to Zipf’s Bad Girls, the young inhabitants weren’t all charged with sexual offenses or serious crimes. Girls also came to Samarcand because they were socially maladjusted or had committed minor misdemeanors, like vagrancy or public drunkenness. Many had no record at all, having been banished to Samarcand by parents who deemed their daughters uncontrollable. Most came from broken homes. Others had been sexually abused in their homes, and somehow received the blame. Zipf says, “They were cotton mill workers, girls from the streets, and sometimes both.” A lot of girls were either poorly educated or thought to lack intelligence. Regardless of whether these deficiencies were innate or stemmed from a lack of educational opportunities, Samarcand tended to identify them as “feebleminded.” It was this labeling that was employed when the state Eugenics Board authorized the regrettable surgeries.

MacNaughton established a relentlessly busy routine of schooling, vocational training, religious instruction and exercise for the girls in hopes of providing each a “useful trade or profession and improving her mental and moral condition.” Several women’s clubs provided financial support for the superintendent’s program. One of them, the King’s Daughters, financed the construction of the Chapel of the Cross, still standing on the campus. The girls made their own uniforms, assisted in meal preparation, and tended to the livestock of Samarcand’s farming operation. The farm boasted an excellent herd of dairy cattle, courtesy of Pinehurst kingpin Leonard Tufts, who served on the Board of Managers. There were no fences around the campus, but girls whose misbehavior incurred MacNaughton’s wrath were subject to being locked in their room at Chamberlain Hall — the dormitory for the most difficult girls. They were further stigmatized by having to wear blue bloomers while “honor girls” wore khaki. Moreover, corporal punishment was administered, sometimes brutally. A girl’s unruliness also resulted in exclusion from Samarcand’s occasional fun stuff. According to Zipf, only the better behaved “enjoyed picnics in the woods, wading parties, hikes, attending church and movies, and planned weekend camping parties in the summer.”

While North Carolina’s legislators enthusiastically created Samarcand, they were reluctant to fund it. From its inception, the reformatory experienced severe financial woes. The federal government offered a prospective avenue for assistance. During World War I, military leaders and members of Congress viewed with alarm the increasing number of American soldiers infected with venereal diseases. To secure the health of military manpower, those leaders urged the states to step up efforts to restrain prostitution. As incentive for doing so, Congress would help finance state efforts to keep prostitutes and promiscuous “camp girls” far away from military bases. The potential infection of soldiers stationed in North Carolina became a subject of increased attention after Fort Bragg opened.

To convince officials that federal funding of Samarcand was required in order to avoid the prospect of females preying on unsuspecting soldiers, MacNaughton’s 1920 application for federal assistance highlighted the high percentage of Samarcand girls suffering from venereal diseases. Assistance was promptly granted, on the condition that Samarcand confine adult prostitutes in addition to its juvenile inmates. Thus, females ranging in ages of 10 to 30 served time at Samarcand in the reformatory’s early years. Zipf notes that Samarcand’s acceptance of federal funding resulted in its having two conflicting missions. “It housed adolescent white girls in need of redemption as Southern ladies,” she points out, “and also adult prostitutes in need of punishment, treatment, and control.” Years would elapse before the adult prostitutes were sent elsewhere.

During MacNaughton’s 16-year tenure as Samarcand’s superintendent, the reformatory was periodically inspected by the State Board of Charities and Public Welfare and generally passed these reviews with flying colors. MacNaughton would also invite members of the press and public to attend Samarcand’s Field Day and May Day festivities, which showed the campus off at its best. Visitors usually came away impressed, rarely observing any inmates other than smiling, rosy-cheeked, well-mannered honor girls. A typical example was the Washington, D.C., policewoman who, in 1924, gushed, “I did not think it was possible to have such a splendid school for delinquents as was shown me. It has not the atmosphere of a correctional institution but rather that of a boarding school.” In fact, MacNaughton did try to inject something of a prep school atmosphere, convincing state education administrators to grant high school accreditation status for the reformatory’s classroom curriculum in 1930.

In the ’20s, Raleigh News & Observer columnist Nell Battle Lewis was among those writing highly complimentary pieces about Samarcand Manor and Agnes MacNaughton. Admitted to the North Carolina Bar in 1929, it was shortly after Nell hung her attorney’s shingle that shocking events at Samarcand would necessitate a backtracking of her effusive praise.

While most honor girls coped with day-to-day existence at the reformatory, many of the girls housed at Chamberlain Hall — the punishment dorm — seethed with resentment at the bedbugs in the blankets, the harsh discipline, and what they perceived as bogus reasons for their being trapped at Samarcand in the first place. Margaret “Peg” Abernethy was one of the latter, a victim of incest at age 10 by her own father. Her stepmother sent the blameless Peg to Samarcand. She revolted against MacNaughton’s strict discipline and twice tried to run away. Whipped on both occasions with a hickory switch for as long as three minutes, Peg required treatment for her bruises. Samarcand’s disciplinary officer shaved Peg’s head.

On March 12, 1931, Peg learned that one of the girls planned to start a fire at neighboring Bickett Hall. The sight of Bickett burning inspired Peg and fellow inmates Margaret Pridgen and Marian Mercer to plot another arson at Chamberlain. They torched stockings stuffed in the dorm’s attic, but staff quickly discovered the smoldering hose and snuffed out the fire before serious damage was done. Undaunted, Pridgen started a second fire in her room, probably with Peg’s help. The fire went undetected until it was too late. Bickett and Chamberlain Halls, both wooden structures, were engulfed by flames.

MacNaughton obtained confessions from a number of girls, including Abernethy and Pridgen. Those admitting their guilt seemed oblivious to the fact that they were implicating themselves in a crime, which potentially carried the death penalty. Both Abernethy and Pridgen (and others) almost welcomed the prospect of the penitentiary, assuming it would be more bearable than what they perceived to be the hellhole of Samarcand Manor.

Sixteen girls were eventually charged with involvement in the arsons and held for trial at county jails in Carthage and Lumberton. The girls apparently regarded setting fires to be a can’t miss attention-getter, since they ignited new ones in both county jails, each extinguished without much damage. Aghast at the pyromania, press accounts like the one in the Moore County News described the girls in animalistic terms, “distorted with rage,” and “eyes gleaming.”

It was against this ominous backdrop that Nell Battle Lewis agreed to serve as co-counsel with Carthage lawyer George McNeill for all 16 defendants. Having never tried a case of any kind, it seemed in one sense preposterous for the fledgling lawyer to become involved with a major criminal matter — particularly one where the death penalty was potentially involved. The high-profile nature of the case meant there would be intense newspaper coverage. Due to her work as a columnist for the News & Observer, Nell was friendly with the reporters covering the trial. While not initially sympathetic to the girls, the writers liked Nell and were open to hearing her version of the story.

Given the confessions of several of her clients, Lewis had little choice but to claim that conditions at Samarcand had driven the girls to their actions. Putting Samarcand itself on trial, she introduced evidence of squalid conditions, beatings, and the questionable incarcerations claimed by the girls. As Lewis hoped, the newspaper stories began emphasizing the brutal whippings rather than the firebugs’ actions. It did not help the reformatory’s image that several Chamberlain girls had been locked in their rooms for disciplinary reasons at the time of the final fire, and were fortunate to have escaped just ahead of the flames.

Though Lewis realized some girls had little hope of avoiding punishment, her spirited defense resulted in charges being dismissed against two of the girls for lack of evidence. The other 14 were found guilty of the reduced charge of attempted arson. Peg Abernethy and 11 others were sentenced to terms in the penitentiary of 18 months to five years. Pridgen and another girl received suspended sentences — curious leniency in Pridgen’s case, since she admitted setting both Chamberlain fires. McLaurin and Russell’s Wayward Girls, by way of historical fiction, delivers a fast-moving account of the fires and their aftermath.

The offenders were punished, but the trial’s revelations had struck a severe blow against Samarcand Manor. Nelson Hyde’s editorial in The Pilot pilloried the girls’ parents, the reformatory, and a North Carolina child welfare system that had driven girls with no previous criminal records to arson. “Weren’t we all on trial for permitting conditions to exist which culminate in sixteen youthful members of society, our neighbors’ children if not our own, facing charges for committing a capital offense,” Hyde wrote. ”And what are we going to do about it? “

The state launched an investigation that resulted in the end of corporal punishment at Samarcand, and a new policy in which only girls convicted of offenses would be admitted. Girls under the age of 10 would no longer be accepted. The events exacted a huge toll on MacNaughton, who took a leave of absence in 1933 and retired a year later.

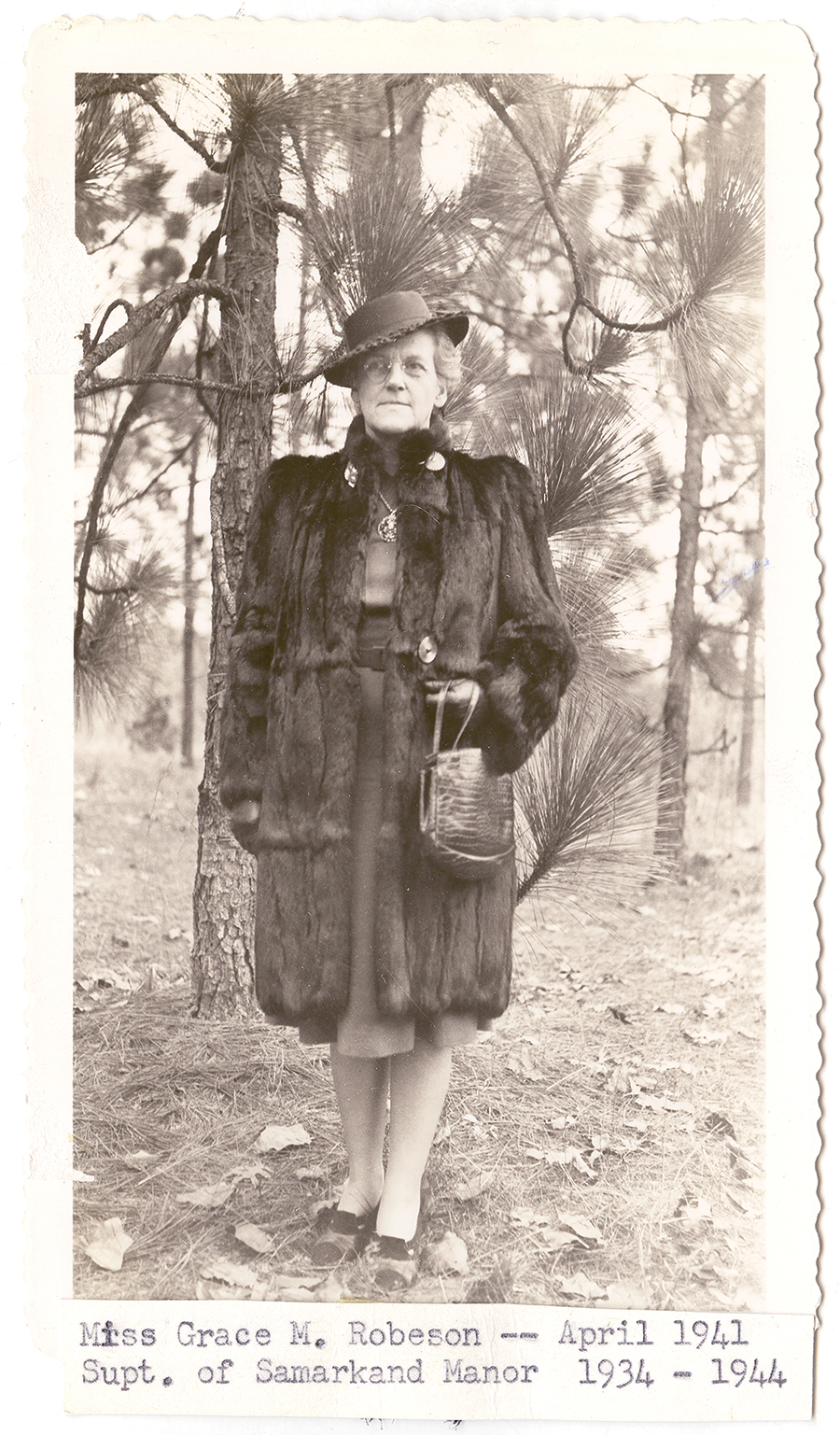

Grace Robson was named to succeed MacNaughton. According to Zipf’s Bad Girls, Robson’s hiring heralded for Samarcand inmates a new era of psychological testing, and classification. Her program sought “to separate the fit from the unfit and to determine a recommendation on sterilization.” Today, we consider forced sterilizations (eugenics) to be an inhumane practice right out of Nazi Germany’s playbook. But such surgeries were legally sanctioned for decades by North Carolina’s General Assembly. The law allowed sterilization of “any mentally diseased, feebleminded (typically an individual with an IQ below 65) or epileptic inmate or patient,” or where social workers believed that an individual would procreate a child “with a tendency toward serious or mental deficiency.” The state established a Eugenics Board in 1933 to provide some semblance of due process for helpless girls before their ability to bear children was surgically removed. But that board served primarily as a rubber stamp for the recommendations of Robson and like-minded administrators at other institutions. Sterilizations of Samarcand’s girls were performed at Moore County Hospital, and the girls recuperated at Gardner Hall.

From 1929 to 1950, 2,538 forced sterilizations were performed in North Carolina, the majority on white females. At least 293 Samarcand girls were sterilized. The last recorded Samarcand sterilization was in 1947. North Carolina was hardly alone in promoting eugenics — 32 states allowed it in one form or another. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote that “three generations of imbeciles are enough,” in a 1927 U.S. Supreme Court decision rejecting a challenge to Virginia’s eugenics law. North Carolina, however, is generally recognized to have been the most aggressive of the states in promoting the practice.

Post World War II, support for forced sterilizations waned, but in North Carolina the program actually gained steam by targeting female recipients of Aid to Dependent Children (ADC), at least half of whom were African-Americans. The Eugenics Board was finally abolished by the state in 1977, but laws permitting forced sterilizations were not actually repealed until 2003. North Carolina Governor Mike Easley issued an apology to the victims and, in 2013, the General Assembly passed an appropriations bill authorizing up to $50,000 per person to compensate those sterilized pursuant to the order of the Eugenics Board.

Certainly the fact that Samarcand was perpetually underfunded made it difficult for Robson to operate the place efficiently. World War II caused even greater budget trimming and a significant loss of personnel. Samarcand barely survived the war. Robson’s tenure as Samarcand’s superintendent ended in 1944. She was succeeded by Reva Mitchell, who served in the post for nearly 30 years.

After the war, conditions and funding markedly improved. By 1955, the campus sported an entirely new look with 11 new buildings. Four more were erected in the following decade along with a recreational park and lakeside theater, pool and numerous plantings. In the ’60s the institution started receiving African-American girls.

In 1974 juvenile boys were admitted to Samarcand for the first time. The percentage of boys in the Samarcand population gradually increased over time. Andy Auman was appointed as Samarcand’s director (a title change from superintendent) in 1986. He stayed until 2002. Auman’s tenure coincided with the reformatory’s transition from focusing on detention to emphasizing individualized therapy, counseling, education and rehabilitation. The facility was formally renamed the “Samarcand Youth Development Center.” Today, Auman credits the shift with enhancing the ability of many Samarcand juveniles to make better lives for themselves. Now retired and living in Aberdeen, Auman expressed pride in the many dedicated Samarcand teachers and staff while acknowledging it could sometimes be a difficult place.

During Auman’s time at Samarcand its population steadily dwindled as juvenile offenders were housed in smaller group facilities closer to their homes rather than in large centralized, and expensive, reformatories. Finally, the General Assembly opted to close the facility, and on June 30, 2011, the last 26 teenagers vacated the campus.

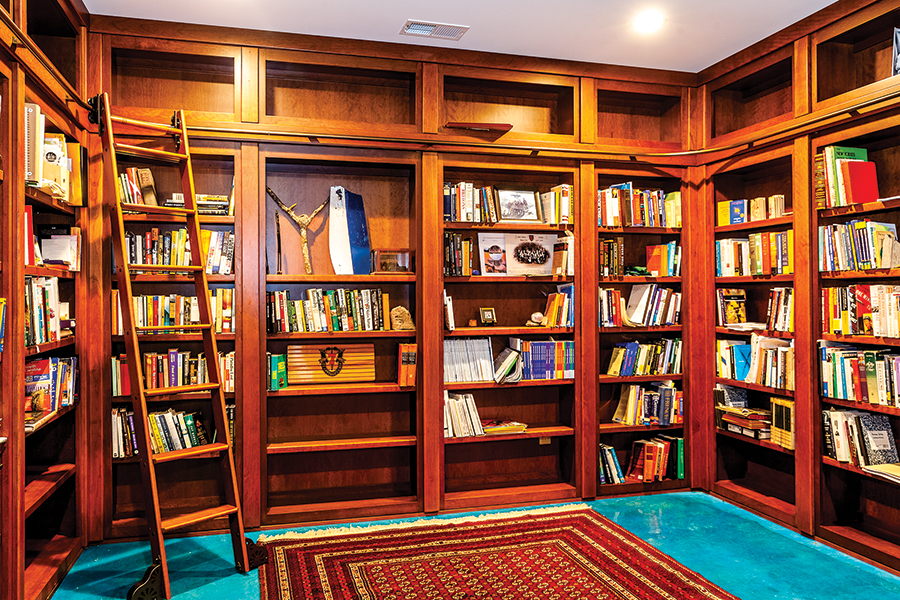

Led by state Representative Jamie Boles, the General Assembly transformed the old reformatory into the Samarcand Training Academy, which opened in 2015. Fourteen of Samarcand Manor’s buildings have already undergone (or soon will) substantial renovations for dormitory and classroom use. The facility is equipped with every type of interactive training currently available in the law enforcement field. There is a five-panel simulator that can place a trainee in virtual reality scenarios, like school shootings, and confront the trainee with up to 230 variations of visual images from a 300-degree range. The simulator can be programmed to replicate the real-life facilities the trainees will be protecting. The Firearms Training Center, completed in June 2017, is the finest in the state, testing all aspects of marksmanship from short-range handguns to long distance sniping. A new dining hall is under construction. When completed in full, Samarcand Training Academy will total 168 bedrooms and 11 classrooms funded by expenditures exceeding $23 million.

Members of over 20 state law enforcement agencies have taken advantage of Samarcand Training Academy’s facilities, including the State Bureau of Investigation, Department of Corrections, and the Alcohol Law Enforcement Agency. Local police forces of Moore County and school resource officers committed to ensuring student safety have received training since the facility opened. In 2017, 955 students attended Samarcand Training Academy; many of them engaged in intense four week courses of study.

“For over a century, whether the property was occupied by Marienfield, Samarcand Manor and now the academy, it has always been used for educational and training purposes,” says the academy’s director, Jordan.

The State Home and Industrial School for Girls opened on Sept. 17, 1918. Eddie Russell, an alum from Andy Auman’s teaching staff who taught at Samarcand from 1985-94, considers those nine years one of his most gratifying experiences. While acknowledging the negativity in Samarcand’s past, he points out that successful rehabilitation of many young men and women also occurred there and that achievement should not be overlooked. “You claim it for both the fame and the shame,” he says. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.