Book Bonanza

October 6: Sharon Granito talks about her new children’s book, The True Story of Elmo, at The Pilot, 145 W. Pennsylvania Ave., Southern Pines.

October 7: Louise Marburg, author of No Diving Allowed, has a conversation with Katrina Denza at The Country Bookshop, 140 N.W. Broad St., Southern Pines.

October 12: Lee Pace discusses his new book, Good Walks: Rediscovering the Soul of Golf at Eighteen of the Carolinas’ Best Courses, with Jim Moriarty at The Country Bookshop.

October 13: Pinehurst author Tony Rothwell appears at the Weymouth Center for Arts and Humanities, 555 E. Connecticut Ave., to talk about his new book, Love, Intrigue and Chicanery, inspired by the work of English satirist James Gillray.

October 20: Walter Bennett discusses his new book, The Last First Kiss, at The Country Bookshop.

October 24: Elizabeth Emerson talks about her new historical biography, Letters from Red Farm: The Untold Story of the Friendship between Helen Keller and Journalist Joseph Edgar Chamberlin, at The Country Bookshop.

October 28: Michael Almond shares his debut novel The Tannery at the Country Club of North Carolina.

November 4: Kristy Woodson Harvey returns with her book Christmas in Peachtree Bluff at The Country Bookshop.

For information and tickets about all of the above, go to www.ticketmesandhills.com.

Everything That’s Old Is New Again

The 2021 Fall Street Fair in Cameron, featuring the town’s rich antique marketplace, begins at 9 a.m. on Friday, Oct. 1, and ends on Saturday, Oct. 2. There will be food, fun, and lots and lots of old stuff for sale. Wander the streets of downtown Cameron, N.C. 24-27. For information visit www.townofcameron.com.

Satire on Parade

The Country Bookshop is hosting an event at the Weymouth Center for Arts and Humanities, 555 E. Connecticut Ave., Southern Pines, on Oct. 13, where Pinehurst author Tony Rothwell will discuss his new book, Love, Intrigue and Chicanery, and share a selection of the prints by the English satirist James Gillray that inspired it. You can pre-register at www.ticketmesandhills.com.

On Sunrise Square

October’s First Friday, which for the impatient among us happens to be Oct. 1, features the Sam Fribush Organ Trio with Charlie Hunter. All the usual accoutrements apply: food trucks, sponsors, stuff to eat and drink, and beer from the Southern Pines Brewery. No rolling, strolling, jogging or jumping coolers allowed. And please leave Cujo at home. The square is adjacent to the Sunrise Theater, 250 N.W. Broad St., Southern Pines. For information call (910) 692-3611 or go to www.sunrisetheater.com.

Heritage Fair and Fundraiser

The 13th Annual Shaw House Heritage Fair and Moore Treasures Sale takes place Saturday, Oct. 9, from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. at the Shaw House, 110 Morganton Road, Southern Pines. The all-day event benefits the nonprofit Moore County Historical Association and offers baked goods, live music, and demonstrations of old-time crafts. There are farm animals for petting and American Revolution War re-enactors for learning. For more information call (910) 692-2051 or visit www.moorehistory.com.

Home Again

The Carolina Philharmonic will open its 13th season on Thursday, Oct. 7, at 7:30 p.m. at BPAC’s Owens Auditorium, 3395 Airport Road, Pinehurst. For its return to live performances Maestro David Michael Wolff has planned a high-energy celebration featuring Broadway’s Catherine Brunell and James Moye. Then, on Friday, Oct. 29, at 6:30 p.m., the Philharmonic will hold its annual gala fundraiser at the Fair Barn, 200 Beulah Hill Road S., Pinehurst, in support of its music education programs. Hors d’oeuvres and wine pairings will be accompanied by the delightful jazz songstress Hilary Gardner. For additional info call (910) 687-0287 or visit www.carolinaphil.org.

Live After Five

Get your shag on with beach music by The Sand Band from 5 p.m. to 9 p.m. on Friday, Oct. 8, at Tufts Memorial Park, 1 Village Green Road, Pinehurst. Eryn Fuson is the opening act for this family-friendly evening of music, dancing, food and beverages — adult and otherwise. No outside alcohol allowed, but bring your lawn chairs and your dancing shoes. For more information go to www.pinehurstrec.org.

Boo Ya’ll!

Children 12 and under can trick-or-treat at the downtown businesses in Southern Pines, then gather for Halloween-themed games, crafts, activities and a best-dressed dog costume raffle at the Downtown Park, 145 S.E. Broad St., Southern Pines, on Friday, Oct. 22. Don’t forget to bring a carved pumpkin to enter in the pumpkin carving contest. Stay for SCOOB! starting at 7 p.m. For information call (910) 692-7376.

Tickling the Ivories

Renowned concert pianist Solomon Eichner, who made his debut at Carnegie Hall in 2016, will be performing selections of romantic music and jazz-influenced compositions in the Great Room of the Boyd House at the Weymouth Center for Arts and Humanities, 555 E. Connecticut Ave., Southern Pines, on Sunday, Oct. 24. Tickets are $25 for members and $35 for non-members. For information and tickets go to www.weymouthcenter.org or www.ticketmesandhills.com.

Up in the Air

The Festival D’Avion, a celebration of freedom and flight, returns for 2021 on Friday, Oct. 29, at 5 p.m. at the Moore County Airport, 7425 Aviation Blvd., Carthage. The band On the Border — The Ultimate Eagles Tribute will perform. The festival continues Oct. 30 at 10 a.m. with the aircraft flyout from 4 p.m. to 6 p.m. For information and tickets go to www.ticketmesandhills.com.

Boiled Over

Enjoy a low country boil catered by Giff Fisher’s White Rabbit Catering from 6 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. on Wednesday, Oct. 27, with the proceeds benefiting the Given Memorial Library, 150 Cherokee Road, Pinehurst. For more information call (910) 295-3642 or visit www.giventufts.org.

Jazz on the Grass

Enjoy live jazz with Al Strong and the “99” Brass Band and a boxed brunch by Baton Rouge Cuisine for a Mardi Gras-inspired Halloween celebration at the Weymouth Center for Arts and Humanities, 555 E. Connecticut Ave., Southern Pines. For information and tickets go to either www.weymouthcenter.org or wwwtickemesandhills.com.

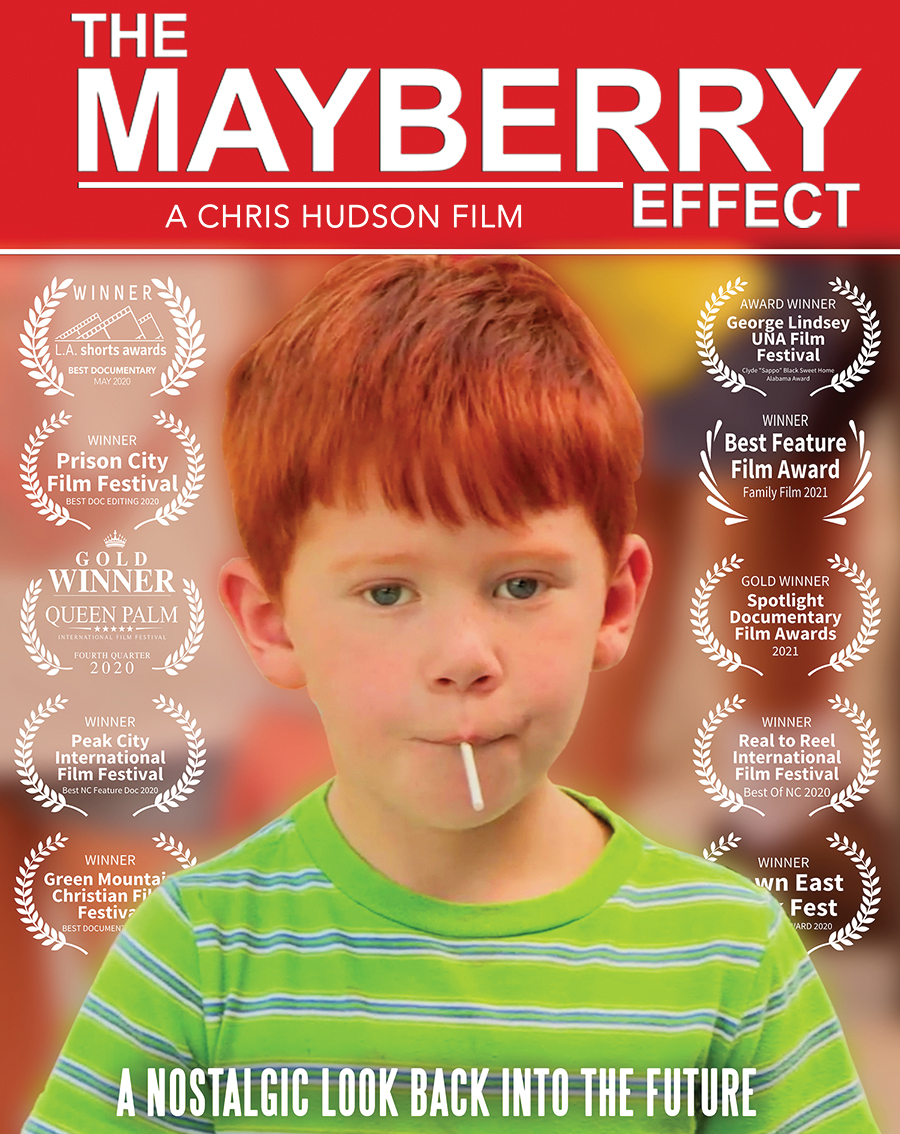

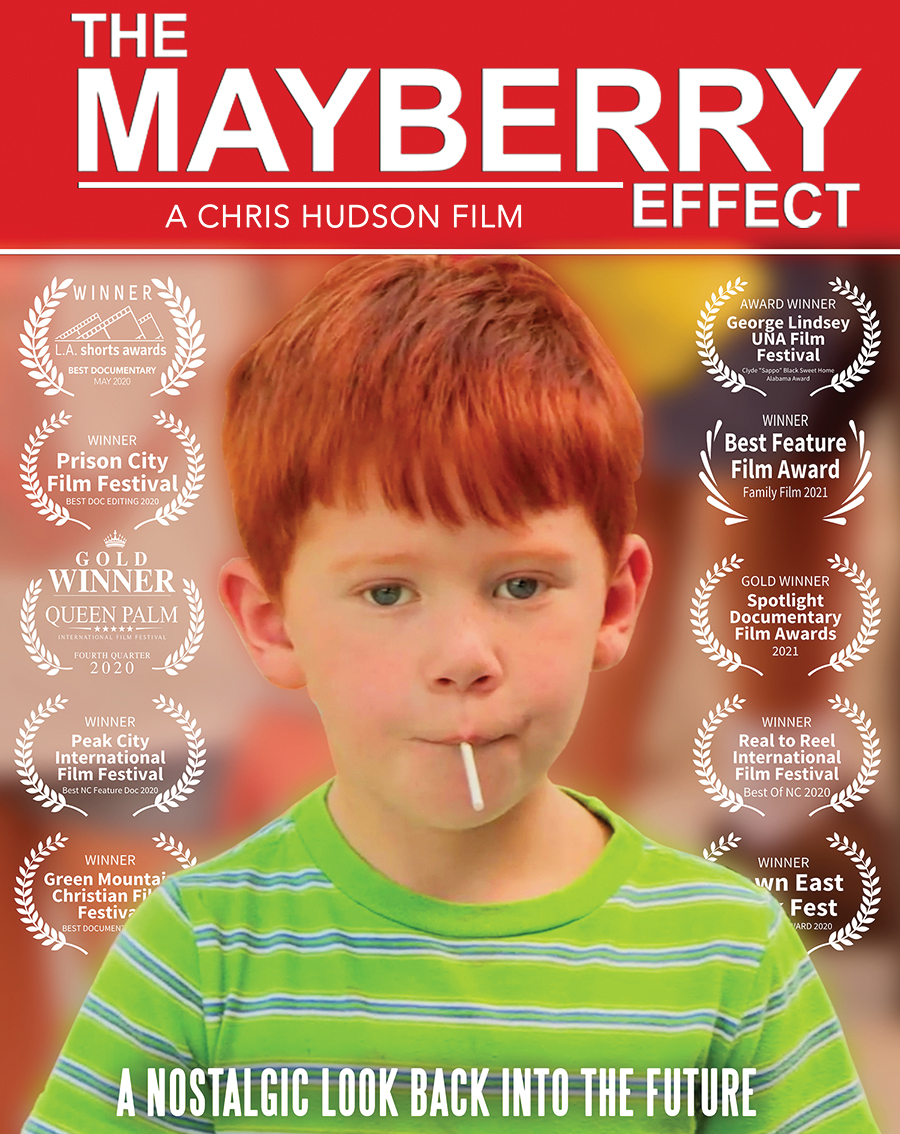

Barney, Floyd, Otis, et al.

Few things have the ability to tug at North Carolina heartstrings like The Andy Griffith Show, an imaginary land where everything, it seems, is a morality play. Independent filmmaker Chris Hudson, born in Moore County and raised in Charlotte, recently released a 90-minute documentary, The Mayberry Effect, a project five years in the making that sees the fictional Mayberry through the eyes of those who never left it — the re-enactors who inhabit the characters, quote their lines and stroll down to the ol’ fishing hole in the land of nostalgia. The film is distributed digitally in the U.S. and Canada by Gravitas Ventures. The link on iTunes is https://itunes.apple.com/us/movie/the-mayberry-effect/id1584316675. You can learn more by visiting Hudson’s website, www.TheMayberryEffect.com.