Bowled Over

Goodies in a gourd

By Jan Leitschuh

And so the seasons change.

The morning freshness in the air and the autumnal shifts in foliage color reinvigorate our heat-saturated souls. Naturally, we yield to the urge to celebrate the transition to coolness, happily sampling the seasonal pumpkin spice lattes and apple hand pies, and the return to outdoor enjoyment.

So, too, we decorate our homes with pumpkins, gourds, squashes — colorful symbols of the harvest abundance of summer, stored for winter feasting. Around Thanksgiving, the fall cucurbit show can be turned into nutritious meals and side dishes.

Eating a squash isn’t the only possibility for festive fall culinary adventures. Get your gourd on. Creativity increases festivity. C’mon, unleash your inner Martha Stewart, in service to the season.

No doubt, squashes and pumpkins are good eating. They are nutrient dense, with lots of vitamins, minerals, and gut-soothing fiber but relatively few calories.

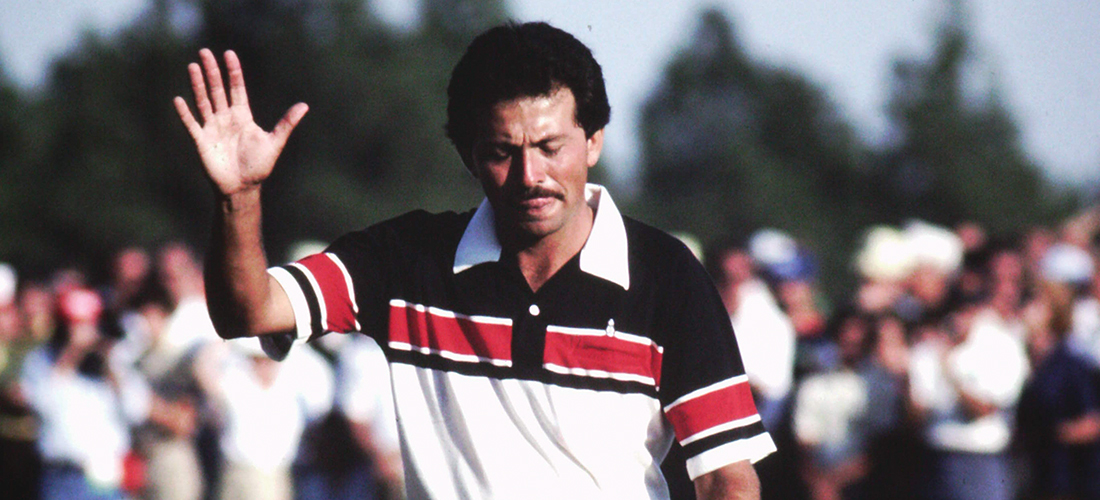

But we are talking fun here. To add a bit of thoughtful eye candy to the dinner table, we can skip the ceramic soup tureens, and the cute serving dishes shaped like autumn produce, and go directly to the real deal. Use your fall pumpkins, green and tan squashes and Jack-B-Little minis as the serving container.

Long ago, I tumbled to this at a fall potluck. I made a pile of buttery sweet potatoes mashed with a little orange juice, maple syrup and bourbon. The concoction was delicious, but in a bowl the brown-orange blob was visually uninspiring. I had a mid-sized pumpkin on hand, and it looked to be perfect for my presentation upgrade.

After cutting off the pumpkin top and scooping out the seeds, I put the hollowed globe in a baking pan and roasted at 350 degrees for 20-30 minutes. I wanted my “bowl” hot enough to keep my mashed sweet potatoes warm, but not so roasted that its walls collapsed and its pretty orange color changed. After I spooned the mash inside, I topped it with pecans and brown sugar, and stuck the top back on partway, serving spoon sticking out. My bourbon mash stayed hot, and the serving vessel brightened the autumn potluck table.

A large pumpkin, hollowed out and lightly seasoned and baked, could also hold soup. The seasonal “tureen” is a conversation-worthy centerpiece in itself. Tuck a few ears of colorful Indian corn at the base, if desired. A meaty tan or green heirloom pumpkin would be extra special.

Now, wouldn’t a ginger-peanut-butternut soup taste extra good in it?

Children love the smaller pumpkins as serving vessels. Pie pumpkins are a good size for soup and, who knows, could a serving of vegetables in one of the “Littles” encourage consumption?

Kids aside, small pie pumpkins could dish up pretty individual servings of, say, a coconut-pumpkin curry. The orange and white mini-pumpkins, so cute and readily available in supermarkets this time of year, could even dress up small quantities of something wildly spicy, say a Thai sauce, hot pepper jelly or Mexican salsa.

Squashes can get in on the action too. A halved acorn, delicata or butternut squash, seeds removed, can be brushed with oil and seasoned before baking. The heat caramelizes the sugars in the squash for a richer flavor. Use your squash as a side dish, as is.

A fancier method is to cool the baked squash, scoop out the roasted flesh, combine with some onions, rice, seasonings and ground beef, and return the mix to the shell. Top with a little shredded cheese for a quick broil. Dinner on the half shell.

Or, combine roasted squash mash with chopped fall apples and a little cinnamon, raisins and brown sugar for a nutritious dessert. The colorful striped “carnival” acorn squash would be spectacular here.

Now that you are planning to put that extra Halloween pumpkin to work doing double duty, you’ll want something warm to put inside it. Why not try this autumnal recipe, packed with cool-weather veggies, from BrokeAss Gourmet:

Peanut-Ginger Soup

Ingredients

2 tablespoons olive oil

1 1/2 cups broccoli florets

2 medium-sized carrots, cut into coins

1 tablespoon grated fresh ginger

4 cloves garlic, chopped

1/2 teaspoon cayenne pepper

1/2 teaspoon dried basil

1/4 teaspoon crushed red pepper

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon pepper

1 14-ounce can vegetarian vegetable stock

1 28-ounce can diced tomatoes

6 tablespoons peanut butter

Directions

In a large soup pot, heat the olive oil over medium heat and sauté the broccoli, carrots, ginger, garlic and spices until veggies are tender. Add the stock, tomatoes and peanut butter. Reduce the heat and simmer for 20 minutes, stirring occasionally. Serve and top with a few crushed peanuts. Serves 4. PS

Jan Leitschuh is a local gardener, avid eater of fresh produce and co-founder of Sandhills Farm to Table.