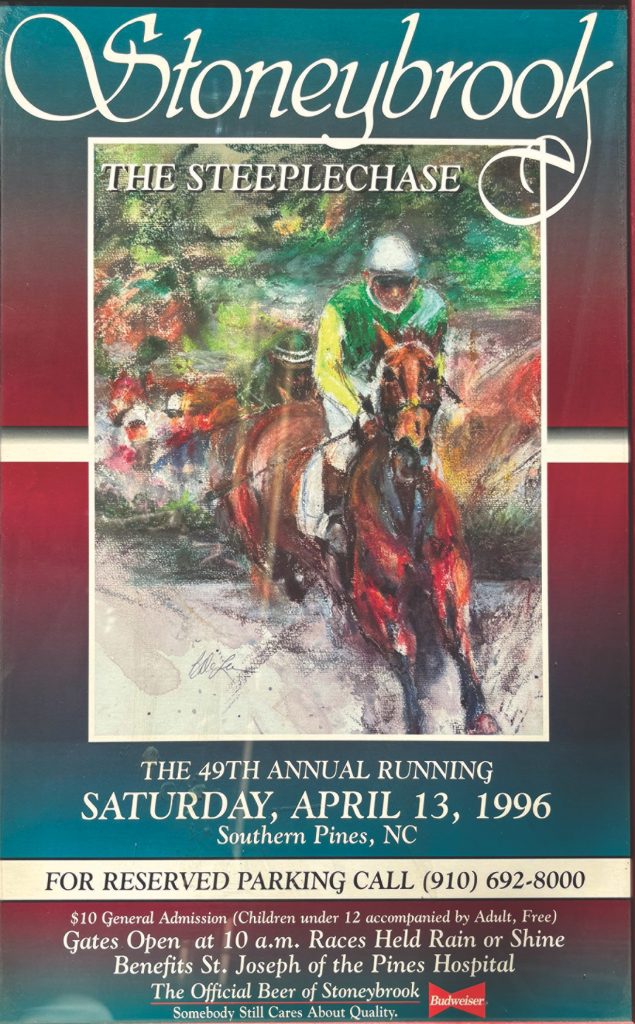

STONEYBROOK REMEMBERED

Stoneybrook Remembered

A springtime tradition like no other

By Chrissie Walsh Doubleday and Tara Walsh York

Elevated to one-word status, the locals simply called it Stoneybrook. But it was much bigger than just a day at the races.

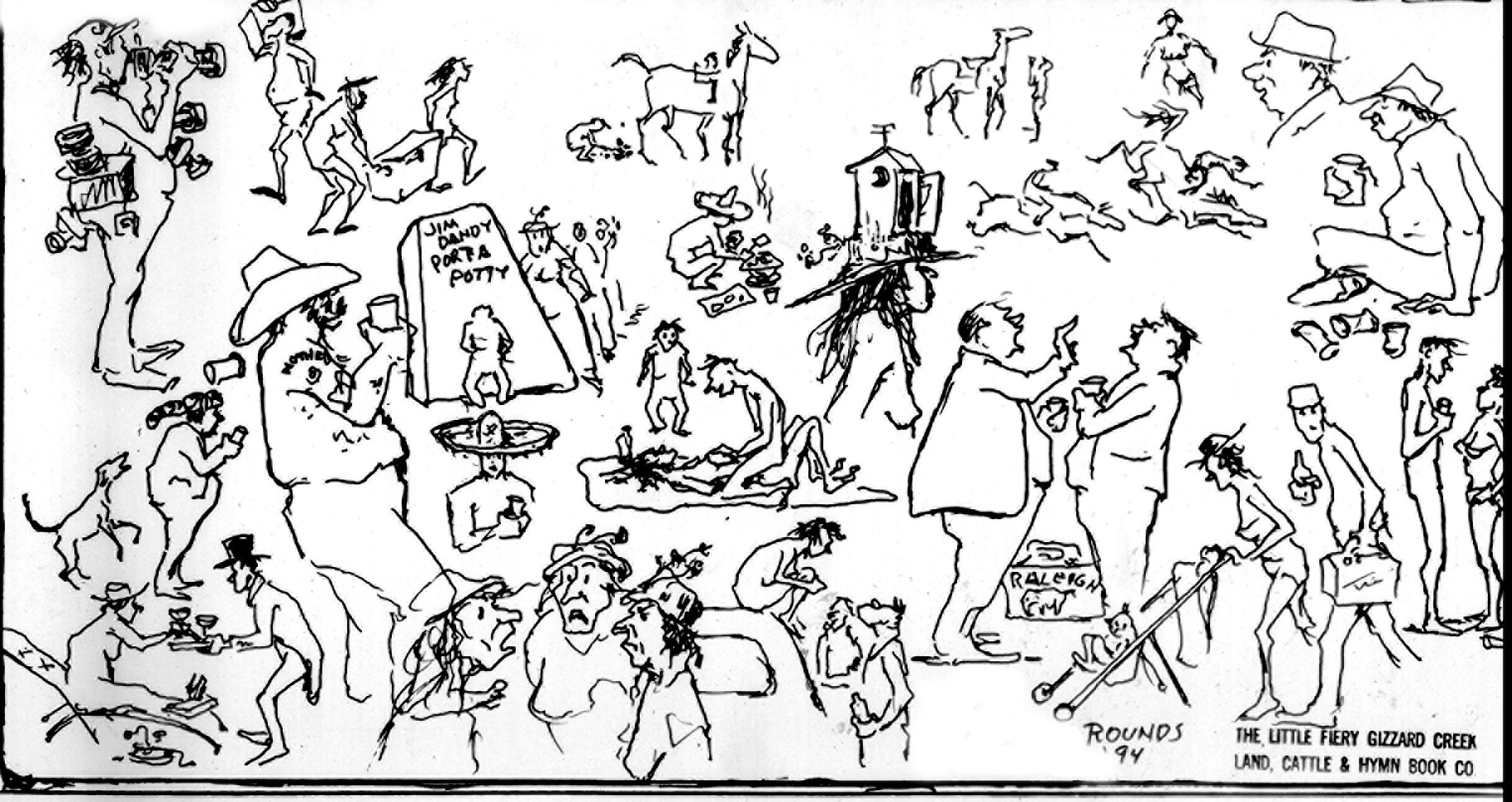

The Stoneybrook Steeplechase was an outdoor cocktail party rivaling the grandest in the Southeast, and once you went, you never wanted to miss it again. Whether folks donned fancy hats and dined at banquet tables adorned with fine linens and chilled Champagne, sat on the back of a pickup truck with a bucket of Kentucky Fried Chicken and a cooler of beer, or spread a blanket on the grass with a picnic basket, it was the place to be. More than just a lively celebration, though, Stoneybrook embodied the thrill of horse racing.

The perfect parking spot was as coveted as a family heirloom. People arrived on foot or by bus, in cars or by limo, but regardless of how they got there or where they came from, when they heard the announcer say “The flag is up!” they raced to the rails to watch. At its peak, nearly 40,000 spectators packed into Mickey Walsh’s Stoneybrook Farm, transforming it into a carnival of energy and tradition. It was the first sunburn of spring, and the ultimate mingling of community and family.

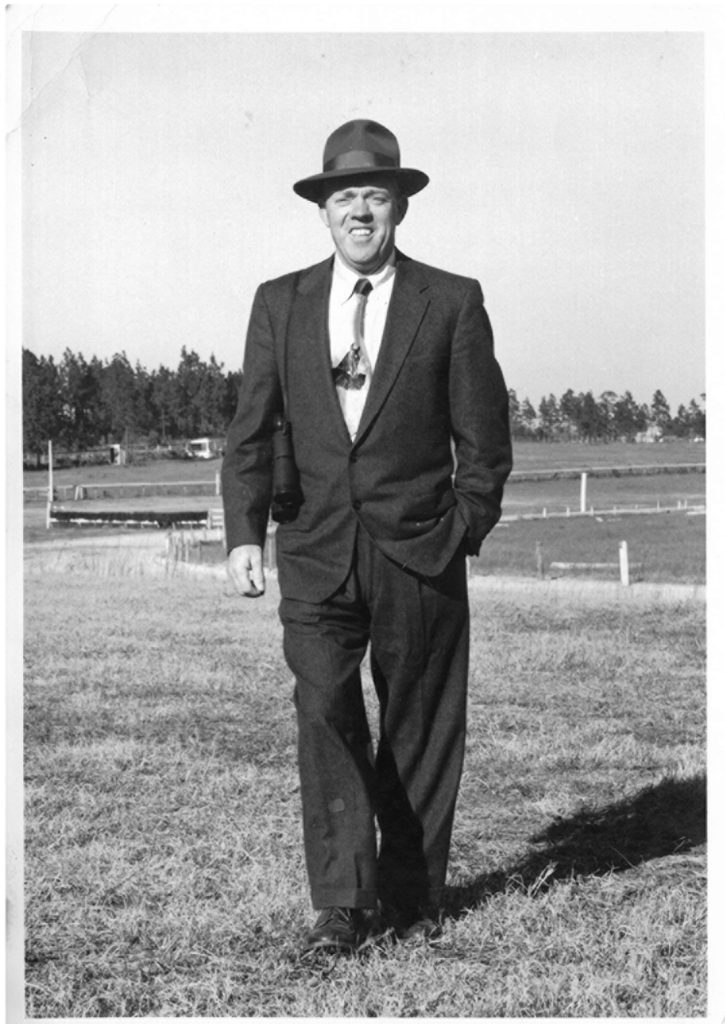

On St. Patrick’s Day 1947 Michael G. “Mickey” Walsh, an Irishman from Kildorrery, County Cork, Ireland, brought his dream of starting a steeplechase race to life on his 150-acre farm in Southern Pines. That year, the first Stoneybrook Steeplechase set the stage for nearly half a century of camaraderie, equestrian excellence and cherished memories — not just for the thousands who attended, but especially for Mickey’s own family.

After immigrating to the United States in 1925, Walsh gained fame in the show jumping world, where his horse, Little Squire, achieved a remarkable three consecutive wins at Madison Square Garden. With ambitions that stretched beyond show horses Walsh settled in Southern Pines in 1944 with his wife, Kitty, and transitioned to steeplechase racing, where he became the nation’s leading trainer from 1950 to 1955. The Stoneybrook Steeplechase would become part of the National Steeplechase and Hunt Association in 1953 and one of the premier horse races in the Southeast.

The success of Stoneybrook relied heavily on the community. The Knights of Columbus organized the parking logistics and directed the influx of visitors on race day, and in the spirit of community that defined Stoneybrook, profits from the event were donated to St. Joseph of the Pines, a nursing home. Within the Walsh family, the event was a labor of love. Marion Walsh, Mickey’s daughter-in-law, managed the Stoneybrook office for many years before the responsibility fell to Phoebe Walsh Robertson, Mickey’s youngest daughter. From selling parking spots to securing sponsorships or working with the horses, all the Walsh women played a vital role in sustaining the tradition.

For the Walshes, Stoneybrook was far more than a public event — it was a cornerstone of their lives. The farm was a haven for Mickey’s children and grandchildren, who spent their days riding horses, playing in hay barns and absorbing the rhythms of farm life. Duties like mucking stalls and riding racehorses before school cultivated a deep appreciation for hard work and horsemanship.

Mickey’s daughters Cathleen, Joanie, Audrey and Maureen were accomplished riders, and raced a time or two. Later, his grandson, Michael G. Walsh III, followed in their footsteps, becoming a leading amateur jockey. In one poignant moment Mickey watched his grandson race at Stoneybrook, riding every jump in spirit alongside him. When young Michael crossed the finish line in first place, Mickey’s pride was unmistakable, his joy radiating through his smiling Irish eyes. His siblings and cousins shared in the pride, racing to the winner’s circle to surround him for the winning photo.

Stoneybrook weekend was a cherished reunion for the entire family. With seven children and 29 grandchildren, the gathering brought relatives from across the country, including Oklahoma, Boston and New York. Close friends, like the Entenmann family — famous for their baked goods — also attended every year, adding sweetness to the occasion.

The festivities extended beyond race day, beginning with the Stoneybrook Ball on Friday night. On race morning, Grandmom Kitty hosted her renowned Owners, Trainers and Riders Brunch, preparing all the dishes herself. Following the races, the celebration continued with an evening reception for horse owners, trainers and jockeys, featuring music, food and drinks. Sunday brought the weekend to a close with a lively bocce ball tournament hosted by Mickey’s son, Michael G. Walsh Jr.

As each Walsh family member reached adulthood, they embraced the full spectrum of Stoneybrook’s traditions, bringing their friends to share in the magic. The event became a rite of passage, a chance to create lifelong memories and forge lasting connections. Even as the races drew thousands, the essence of Stoneybrook remained intimate for the Walsh family. It was a tapestry of laughter, camaraderie and shared experiences. This sense of togetherness extended to the broader community, where old friendships were rekindled and new ones blossomed.

Mickey Walsh’s passing, in 1993, marked the end of an era. The races at Stoneybrook Farm eventually ceased in 1996, but their impact lingered in the hearts of all who had been part of them, spectator and family alike.

For the Walshes, the memories of those weekends — the excitement of the races, the joy of reunion, the shared pride in their heritage — remained indelible. Though the races ended just shy of 30 years ago, the memories endure, a lasting tribute to Mickey Walsh and the indomitable spirit he embodied.