Passing the musical baton

By Jenna Biter • Photographs by John Gessner

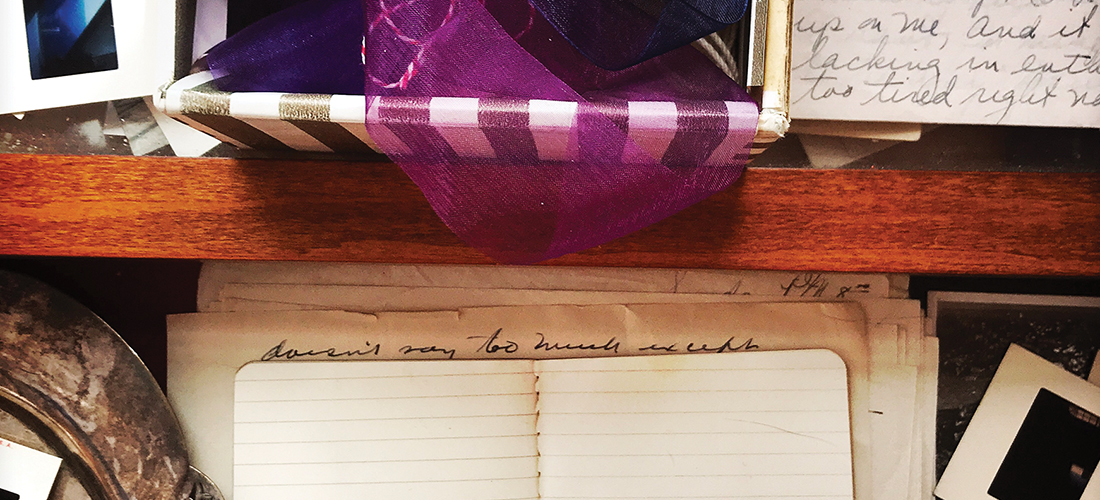

“These my mom made, if you have an interest,” says Janet Kenworthy, motioning to a stack of albums filled with newspaper clippings and concert fliers. Sitting on the wraparound porch of her historic home on Blue Street in Aberdeen, music playing softly, her Jack Russell Tootsie lolling about on a cushioned chair, Kenworthy flips through plastic-sleeved pages, rattling off the names of musicians and bands with encyclopedic ease.

“Laurelyn Dossett, another Grammy winner, she had a song on Levon Helm’s Dirt Farmer. John Cowan, the Voice of Newgrass. That’s Victoria Vox, she’s huge in the ukulele world. Here’s John Ellis.” Asleep at the Wheel, Scythian, Paul Thorn, Amythyst Kiah, Jeff Scroggins and Colorado — the list is almost unending.

As the one-woman force who is The Rooster’s Wife — the live music community-based organization that called Aberdeen’s Poplar Knight Spot home — Janet Kenworthy has curated about 60 shows a year since the organization’s inception. “See, this was the first outdoor show because we started in December 2006,” she says, pointing to a picture of the Carolina Chocolate Drops, a well-known, old-time string band from Durham.

The inspiration for The Rooster’s Wife sprang from Kenworthy’s experiences volunteering in Hurricane Katrina-ravaged New Orleans after her daughter, Helen, was evacuated from Tulane University. “I went to work for the Red Cross and ran a kitchen at a shelter. It was a 400-bed facility, and it was my job to get three hot meals on the table a day,” she says. “You can imagine losing everything and then sleeping in a gymnasium with 400 other people. It’s brutal. It’s shocking, and you’re totally discombobulated.”

One day a woman came through the kitchen’s back door and asked Kenworthy if her teenage son could play his guitar for the shelter’s residents. Mother and son were parishioners from a West Mississippi church who wanted to help any way they could. Music was their offering.

It was a time for small generosities. Local beauty and barber school students were giving haircuts, beard trims and manicures. Kind gestures eased the shock of sudden homelessness. When the gangly boy — tall in that teenage kind of way, trying not to be tall — started playing New Orleans-style guitar and taking requests for old standards, people reconnected. He became a regular.

“Music spurs memory,” says Kenworthy. “People were talking. They were reminiscing. Some were singing. Some were dancing. I’ve always known about the redemptive nature of music, but this was really about the revitalization of the inner soul of these people. Hearing this music, their music, was really helpful. I wanted to bring music to this community.”

Jon Parsons, then the executive director of Sustainable Sandhills and one-third of the acoustic trio the Parsons, and Joe Newberry, a North Carolina songwriter and musician known for his clawhammer banjo-playing, introduced Kenworthy to the concept of house concerts. Within three weeks — “Well, maybe it was three weeks,” she says — The Rooster’s Wife took flight. She explains the name with a sing-song question and answer.

“We kept chickens. Who lays the eggs?”

“The hen.”

“Who raises the chicks?”

“The hen.”

“Who keeps the henyard straight?”

“The hen.”

“Who makes a lot of noise and has a lot of big feathers?”

She raises her eyebrows.

“The rooster.”

Ahhhh.

“I was doing all the work,” she says, “but I didn’t want my name on it, per se. It’s always been about the music, not about me.”

Her first venue was her home, a picturesque, turn-of-the-20th-century residence with a sprawling yard where she raised her brood of four. “We started here, right in this house. I put up fliers and sent postcards because we didn’t have a mailing list. My address book was my mailing list. We just called and invited people to come, and they did.” One hundred and five people showed up to that first house concert featuring the Parsons.

“People are listening to great music, eating my food, drinking my booze, and giving me money. Oh, it’s just business as usual, except for the giving me money part,” Kenworthy says with a laugh. “So, that’s how it started. We did four years of house concerts, and I concurrently started an outdoor series at the Postmaster’s House.”

It wasn’t until her bathroom door had to be wrenched from its hinges that The Rooster’s Wife renested at the Poplar Knight Spot, located at the intersection of Poplar and Knight streets, only three blocks from her house. “There was one show where a lady got locked in the bathroom. She was calling on her cellphone and beating on the door, but there was a big, rowdy show going on,” Kenworthy remembers. “At the set break, a couple of guys had to take the door off the hinges to get her out. It’s an old house, and it’s like, ‘Who locks the damn bathroom door?’”

The bathroom lockdown wasn’t the only reason for relocating. “The house, it was rockin’ in here,” she says, “but it was also moving furniture. The dining room table would come out here.” She motions to the porch. “And chairs would go in, and enough was enough. My mom and I had the opportunity to buy a building in downtown Aberdeen and renovate it.” And so, in 2009, the Poplar Knight Spot became the home of The Rooster’s Wife.

Sunday evening shows have been Kenworthy’s stock and trade, stretching back to the early days of the house concerts. “There wasn’t anything on Sundays, so I thought, OK, that’s my night. Lots of musicians were interested in having a night to play rather than a dead night,” she says. And it helped that the host and her mother, Priscilla Johnson, were hospitable. Johnson, who lives only a mile down the street, has been a mainstay of The Rooster’s Wife, cooking up sharp cheddar, apple and chutney grilled cheese sandwiches for the musicians, and baking cookies for every show. “I could house people, feed people, pay people and so, it just evolved from there,” says Kenworthy.

The early showtime with its idiosyncratic 6:46 p.m. start was also kid friendly. “There certainly wasn’t anything that welcomed families or small children,” Kenworthy says about live music in the Sandhills, “and I felt it was absolutely essential that they be exposed to good music. I figure, if you never had the flavor, you’re not going to develop the taste.”

Children under 12 were always admitted free at The Rooster’s Wife. A handful of families became Sunday night regulars. “One family had one child when they started coming; now they have three!”

Kenworthy’s own taste for good music developed at a young age. “I grew up in Lexington, Kentucky, and we certainly sang,” she says of her family. A relative was often on the piano and her Uncle Frank, Priscilla’s brother, was a jazz drummer and trombonist. “Music was just part of life,” Kenworthy says.

She attended Presbyterian-based Sayre School from elementary through high school and went to its live music performances every Friday at chapel. “It might be some old biddie from the DAR, or it might be your headmaster’s son’s roommate from Vanderbilt who is Rodney Crowell, multiple Grammy winner,” she says. “You had no idea, but you would be polite and attentive, regardless of who would be on stage.” She can’t quite remember the punishment for turning around to catch a friend’s eye, but she knows it wasn’t worth it.

“Musicians really appreciate an attentive crowd,” Kenworthy says. “I think it’s cultural, learning how to be a good audience. It was incumbent upon me to bring compelling enough programming that the audience would be respectful.” Precisely what The Rooster’s Wife has done for the last 15 years.

During the pandemic, Kenworthy had plenty of downtime to reflect on the future of The Rooster’s Wife and the Poplar Knight Spot. “Everything has its season, and being able to sit and not just be on the hamster wheel gave me time to think.” she says. “People say they’re leaving their job to spend more time with their family, but I actually am.” Her four children and six grandkids are scattered around the world, as far flung as Costa Rica and New York. Maybe it was time to pass her passion on to someone else who loves music.

That person is Derrick Numbers who, along with his wife, Dr. Malgorzata (Gosia) Kasperska, bought the Poplar Knight Spot from Kenworthy in April. “Derrick grew up going to the Bluebird Cafe in Nashville, which is well known for singer-songwriters, and it’s always been his dream to have a venue. And they have a little boy,” Kenworthy says, referring to 8-year-old Logan.

“Every year in April, the Bluebird Cafe did this thing called Tin Pan South where all of the little music venues — a lot of them the size of The Rooster’s Wife — will bring in songwriters, and they’ll do two shows a night for the week,” says Numbers. “And so, you get these amazing people who write songs, and then six months later, you hear them on the radio. That started for me when I was about 14-years-old. I’d go with my dad.” Numbers developed the ‘taste.’

He earned his B.A. in music business from Malone College and interned in Nashville with Dualtone Music Group, the record label for the Lumineers. After his internship, he switched course and joined the military. “We lived in quite a few places, Hawaii, D.C., but I was always going to shows, always buying guitars, all that kind of stuff,” he says. “We ended up at Fort Bragg and found The Rooster’s Wife and Casino Guitars and made a home here.”

Numbers heads up marketing and videography for Baxter Clement’s Casino Guitars in Southern Pines. “As part of my video stuff, I try to shoot a lot of artists, interview them, get them on film. I’ve interviewed guys from Kiss to Paul Thorn,” he says. “I actually interviewed Paul Thorn when he played in Aberdeen, I think it was maybe four years ago. So, that was one of my first experiences with The Rooster’s Wife — seeing an artist that I really loved.” When the opportunity to buy the Poplar Knight Spot came along, the couple jumped at it.

“Hopefully, we can replicate some of the success that Janet’s had,” Numbers says. “A lot of that success derived from her ability to connect with those artists, make those artists feel at home. That’s a huge thing. Hopefully, we can continue to do that.” But with their own flair, of course.

“The name we’re going with is the Neon Rooster,” says Numbers. “I kind of wanted to have something cool and funky and ours, but with a tribute to the old.” They’re planning to open in September.

“We’re excited to be embraced by the community,” Gosia says. “It’s super important, right? We’re bringing something to the community, but without the community, it will not be a success. I’m hoping that we’re able to fill the gap that Janet created.”

As for the original Rooster’s Wife, Kenworthy is in the reinvention business. “People that came to shows in the beginning knew my dog well. His name was Bert.” He was a Jack Russell like Tootsie and Janet’s show dog. On Sunday nights, he’d lead the way from Blue Street to the Poplar Knight Spot, taking the shortcut over the train tracks.

“The next venture will be Dog-at-Large Productions,” says Kenworthy. “What I intend to be is just running amok . . . whatever the universe provides.” PS

Jenna Biter is a writer, entrepreneur and military wife in the Sandhills. She can be reached at jennabiter@protonmail.com.