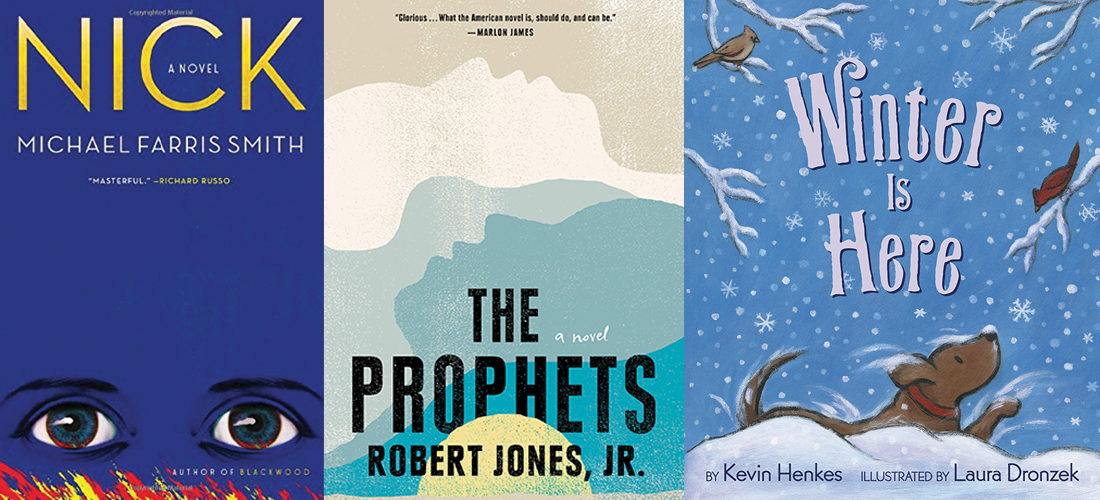

January Books

FICTION

Nick, by Michael Farris Smith

Before Nick Carraway moved to West Egg and into The Great Gatsby, he was at the center of a very different story — one taking place along the trenches and deep within the tunnels of World War I. A romantic story of self-discovery, this rich and imaginative novel breathes new life into a character that many know but few have pondered deeply. Nick reveals the man behind the narrator who has captivated readers for decades.

The Fortunate Ones, by Ed Tarkington

A teenage boy being raised in a low-income area of Nashville by a single mom receives a mysterious scholarship offer to attend an elite private school for boys. Charlie Boykin is thrust into the midst of the children of billionaires and socialites, and the trajectory of his life is altered forever. But was it all worth it? This is a character-driven novel with a storyline as opulent as the mansions within it.

The Good Doctor of Warsaw, by Elisabeth Gifford

Janusz Korczak ran an orphanage for Jewish children in Warsaw, where conditions became increasingly harsh during World War II. Gifford tells his story with moving details of daily life — struggling to find food and to avoid being killed by the Nazis. Over 95 percent of the 350,000 Jews in Warsaw did not survive the war. A story the world must never forget.

The Prophets, by Robert Jones Jr.

A singular and stunning debut novel about the forbidden union between two enslaved young men on a Deep South plantation, the comfort they find in each other, and a betrayal that threatens their existence. In the barn they tended to the animals, but also to each other, transforming the hollowed-out shed into a place of human refuge, a source of intimacy and hope in a world ruled by vicious masters. With a lyricism reminiscent of Toni Morrison, The Prophets masterfully reveals the pain and suffering of inheritance, but is also shot through with hope, beauty and truth, portraying the enormous, heroic power of love.

The Last Garden in England, by Julia Kelly

This is a sweeping novel of five women across three generations whose lives are connected by one very special garden — the Highbury House estate — designed in 1907, cared for during World War II and restored in the present day by Emma Lovett, who begins to uncover secrets that have long been hidden.

The Divines, by Ellie Eaton

Moving between present-day Los Angeles and 1990s Britain, The Divines is a scorching examination of the power of adolescent sexuality, female identity and the destructive class divide. Josephine inexplicably finds herself returning to her old stomping grounds of St. John the Divine, an elite English boarding school. The visit provokes blurry recollections of those doomed final weeks that rocked the community. Josephine becomes obsessed with her teenage identity and the forgotten girls of her one-time orbit. But the more she recalls, the further her life unravels, derailing not just her marriage and career, but her entire sense of self.

A Mother’s Promise, by K.D. Alden

In Virginia in 1927, Ruth Ann Riley was poor and unwed when she became pregnant. She was sent to an institution and her child given up for adoption. All the rich and fancy folks may have called her feebleminded, but Ruth Ann was smarter than any of them knew. No matter the odds stacked against her, she was going to overcome the scandals of her past and get her child back. She just never expected her battle to go to the United States Supreme Court, or that she’d find unexpected friendships, even love, along the way.

The Narrowboat Summer, by Anne Youngson

Eve and Sally are at a crisis in their lives when they each happen upon a narrowboat on a canal owned by Anastasia. Before they realize what they’ve done, Sally and Eve agree to drive Anastasia’s narrowboat on a journey through the canals of England, as she awaits a life-saving operation. The eccentricities and challenges of narrowboat life draw them inexorably together, and a tender and unforgettable story unfolds. At summer’s end, all three women must decide whether to return to the lives they left behind or forge a new path forward.

NONFICTION

Let Me Tell You What I Mean, by Joan Didion

Twelve early pieces never before collected offer an illuminating glimpse into the mind and creative process of Didion. Drawn mostly from the earliest part of her astonishing five-decade career, these are subjects Didion has written about often: the press, politics, California robber barons, women, the act of writing, and her own self-doubt. Each piece is classic Didion: incisive and stunningly prescient.

CHILDREN’S BOOKS

Winter is Here, by Kevin Henkes and Laura Dronzek

When winter comes, it comes soft like snowfall and hard like leaves frozen in ice. Winter comes white and gray and deep, deep blue. From the husband and wife team of Henkes and Dronzek, Winter is Here is the companion to the lovely When Spring Comes and is the perfect introduction to the seasons for young readers. (Ages 1-3.)

A Busy Year,

by Leo Lionni

Winnie and Willie and Woody are friends. First, as January snow falls on Woody’s branches, later as her branches bloom and even later as her leaves begin to fall, the friends experience all a year has to offer. A fun way to learn about the seasons while also zeroing in on the qualities of a good friend, A Busy Year is a classic that deserves a spot on every child’s bookshelf. Arriving Jan. 12. (Ages 2-3.)

Looking for Smile, by Ellen Tarlow

Once in a while, when you least expect it, life gets you down, and you just lose your smile. But sometimes the quiet song of a good friend can make the world bright again. A great story of friendship and of dealing with the downs. (Ages 3-6.)

Just Our Luck, by Julia Walton

In this moving and absolutely hilarious tale, Leo is a high school boy caught up in his own anxiety. He normally keeps his head down, but a fight with another boy at school starts a chain reaction, entangling Leo in something he never would have been part of by choice. This amazing, touching masterpiece is perfect to the very last page. (Ages 13 and up.) — Review by Kaitlyn Rothlisberger. PS

Compiled by Kimberly Daniels Taws and Angie Tally.