A Sandhills Hall of Fame for extraordinary animals

By Bill Case

In 1953, Newport Dream swept honors as the country’s best 2-year-old trotter, winning 11 of 12 races. Following this remarkable campaign, the colt wintered at the Pinehurst Race Track, which, according to the horse’s owner, Octave Blake, provided “the greatest climate in the world to train a horse.” As Newport Dream rested and the ’54 racing season approached, Blake and trainer-driver Del Cameron eagerly looked forward to the prospect of their horse winning one, or all, of harness racing’s vaunted Triple Crown events for 3-year-olds.

But in mid-March, Cameron noticed that the bay was demonstrating acute soreness in his left foreleg. Swollen knees on the trotter’s forelegs were also evident. An alarmed Del consulted Sandhills area veterinarians, but none were able to determine the underlying cause of the horse’s lameness. One vet tried to pinpoint the location of the ailment by blocking a nerve. That treatment backfired, resulting in an infection. “We just couldn’t figure out what was wrong with him,” recalled Cameron. “We had him in bubble baths, diathermy machines, and we tried just about everything.”

In April, the horse was transported to Blake’s Newport Stock Farm in Vermont. But as spring rolled into summer, Newport Dream’s lameness continued. Blake and Cameron feared their champion would not recover in time to compete in the Triple Crown’s first leg, the Hambletonian Stakes, run in August at Goshen, New York. “He was too sore to race, and I couldn’t train him,” reflected Cameron. In late July, Dream’s condition finally improved enough for Octave and Del to enter the colt in the Hambletonian Prep. He ran surprisingly well, finishing second in both heats, and appeared none the worse for wear. Encouraged, the hopeful owner and trainer trailered Dream to Goshen for the main event.

To the astonishment of most, Newport Dream won the Hambletonian’s first heat going away. However, Cameron observed that the horse appeared a bit sore upon stepping onto the track for the decisive second heat. Nonetheless, he managed to maneuver the gritty Dream to a narrow lead at the top of the stretch. As trailing mounts challenged in the final hundred feet, Cameron “reached up and tapped the colt once, and he responded enough to win.”

Horse racing aficionados hailed Newport Dream’s plucky comeback. So did Cameron. “He has a heart as big as that bucket of oats,” gushed the renowned trainer-driver following his sensational ride.

If a Hall of Fame existed for exceptional Sandhills beasts, Newport Dream would get in on the first ballot. And if such a Valhalla existed, he’d have plenty of company. Winning races is one qualification, but others have excelled in their own domains. The Pine Crest Inn’s orange tabby cat, Marmaduke, was such a fixture in his habitat that his exploits (or perhaps lack thereof) were recognized far beyond the county’s territorial limits.

Rescued from the Haven-Friends for Life no-kill shelter in Raeford, Marmaduke came to the Pine Crest a decade ago. Two female orange tabbies of long service, both named Marmalade, successively preceded him as the inn’s resident cat. Marmalades II and I are remembered today with bricks inscribed with their names located at the foot of the Pine Crest’s front door entrance.

Marmaduke was unfriendly and reclusive when he first arrived in 2009. “We advised guests not to try petting him,” recalls Andy Hofmann, a member of the Barrett family that has owned the Pine Crest for decades. But over time, the tabby adapted to his role as the Pine Crest’s unofficial ambassador, warming up to patrons and employees alike. “Now, when our regulars arrive for cocktails around 4:30 p.m.,” says Hofmann, “he jumps on their laps.”

Marmaduke’s long tenure has not been without incident. A few years ago, he turned up missing and was feared fur-napped. To the relief of everyone, Marmaduke was returned the following day by a sheepish (and apparently desperately nearsighted) woman who had mistaken the miffed tabby for her own lost kitty.

Today when guests step onto the Pine Crest porch, they often check Marmaduke’s shelter for a bit of reassurance that the venerable and exceedingly well-fed feline still prowls the premises. Like the Putter Boy statue, Marmaduke and the orange tabbies that preceded him — and those who, in the inexorable march of time, are likely to follow — are permanent and beloved Pinehurst sentinels.

There is another Hall-worthy four-legged tourist attraction currently gracing the streets (as opposed to the track) of Pinehurst. Shiloh, standing 16 hands and weighing in at 1,400 pounds, is the friendly, carrot-chomping horse that for 12 years has pulled carriage loads of enthralled visitors through the village’s historic district. Driver Frank Riggs, who operates Carriage Tours of Pinehurst Village Inc., swears the 18-year-old is the ideal carriage horse. “Traffic doesn’t bother Shiloh,” says Riggs. “About the only thing that can startle her are skateboarders whizzing by from behind if she doesn’t hear them coming.”

Riggs obtained Shiloh from Holmes County, Ohio, where she previously pulled an Amish farmer’s buggy. She is the offspring of a Percheron, a large draft horse breed, and a Morgan, a smaller pleasure horse. According to Riggs, that type of crossbreeding is common practice for the Amish.

In 40 years of commercial carriage driving, Riggs has worked with a number of animals in harness. While Shiloh rates as his top horse, he also has fond memories of Moonshine, a mule he drove a few years back. “Moonshine wasn’t at all stubborn. He had lots of personality,” recalls Riggs. “When we’d pass The Village Chapel as church was letting out, he thought everybody was rushing out to see him.”

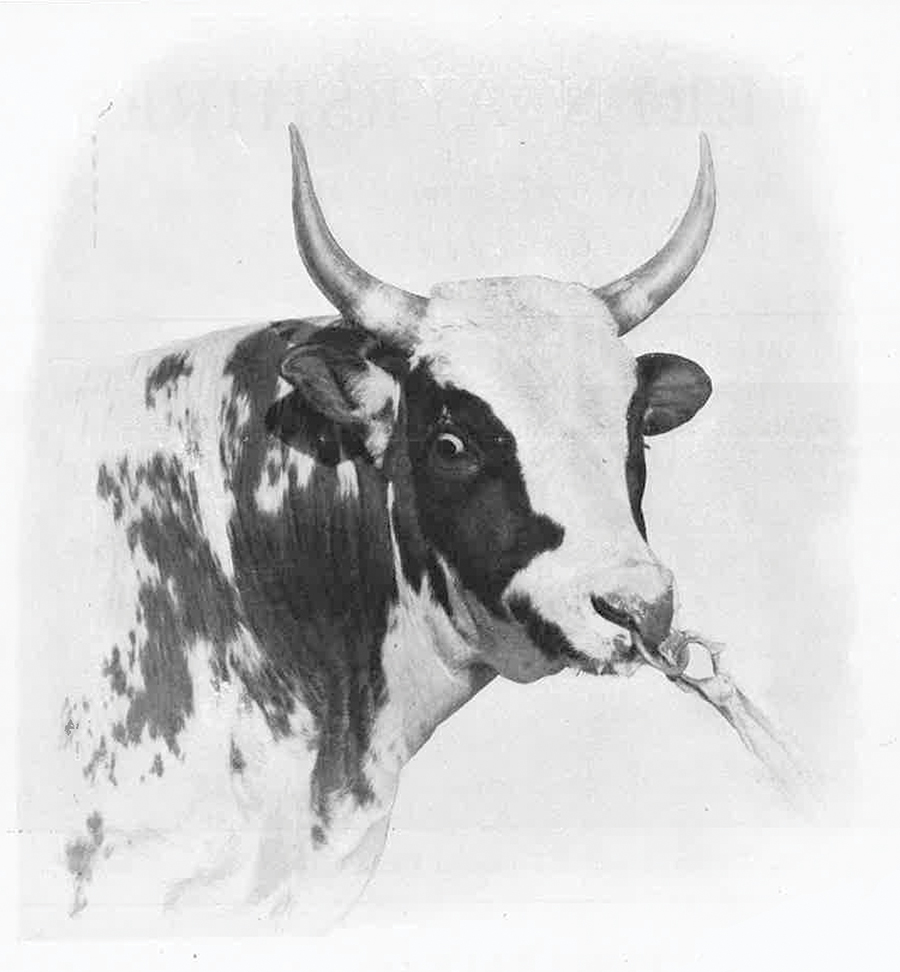

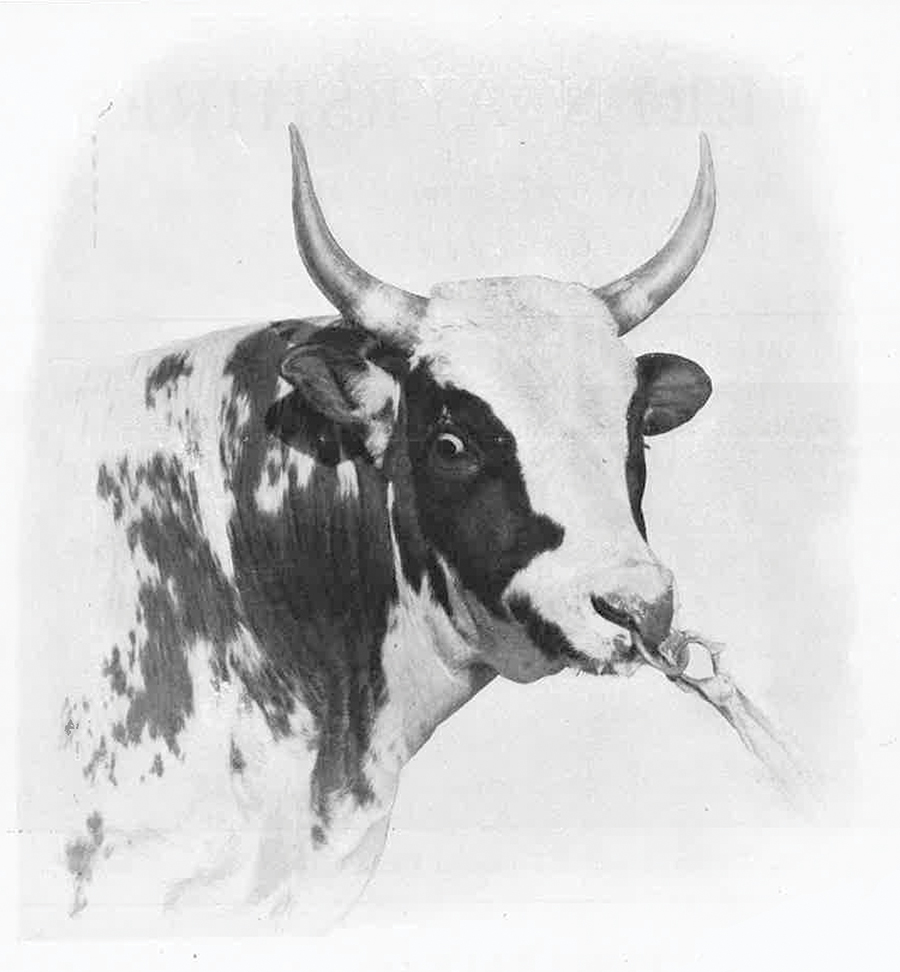

Shiloh and Moonshine aren’t the only working stiffs to have generated profits for their owners. Farm animals have been a staple of the Sandhills’ economy since the area’s settlement a century ago, but the unprecedented milk production of an Ayrshire cow known as Tootsie Mitchell created a truly exceptional income stream, as it were, for one Moore County farmer.

Tootsie’s owner was Leonard Tufts, the Pinehurst kingpin who essentially operated the village and resort as his own private enterprise. Though the innumerable details of managing Pinehurst required his constant attention, Tufts always found time to devote to his favorite pastime — Ayrshire cattle. Some people collect stamps, others collect cows. As president and director of the Ayrshire Breeders’ Association, he immersed himself in the study of cattle breeding genetics. The crowning achievement of Tufts’ applied research was Tootsie, born in 1909. In her 12th year of milking, she produced a prodigious volume of 14,729 pounds of milk and 596.62 pounds of butterfat, much of which was consumed by Carolina Hotel guests. Moreover, Tootsie produced six female calves whose output approached their mother’s remarkable production.

At a 1922 bankers’ conference held at The Carolina, Tufts touted Tootsie’s unparalleled liquefied achievements. Present on the hotel’s grounds was the great cow herself along with a huge can 6 feet in diameter and 17 feet tall, the volume of which matched Tootsie’s total milk production the previous year. An article in the Pinehurst Outlook predicted, “What this remarkable cow has accomplished will be talked about in every county in the state when the bankers go home.”

Animals have caused a commotion in Pinehurst since the earliest days when the depredations of razorback hogs necessitated the erection of a wire fence around the periphery of the nascent town. Then, in 1905, after concluding that showcasing wild animals would provide a novel attraction for resort guests’ children, Leonard Tufts erected a small zoo on land across Palmetto Road from the present Village Chapel. Squirrels, owls, raccoons, opossums, Chinese pheasants, Belgian hares, peacocks and deer were exhibited in confined spaces in the “Deer Park.” The zoo would remain on those grounds until 1949. The final animal to exit was the ancient buck Bluebeard — a resident of Deer Park for so long no one could remember his arrival. Bluebeard surely belongs in the Hall based on his longevity, his association with the long-gone zoo, and the fact that he could well be the only individual deer not associated with Bambi that has a name.

There is another animal that enjoyed a brief sojourn at the Pinehurst Zoo who deserves at least a bronze plaque in the Hall’s hall. During World War II, a black bear cub in Moore County became a national sensation. Gifted by Canadian paratroopers to their brethren in the U.S. Army, Joey found his way to Camp Mackall in 1943 as the beloved mascot of the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment. The nearly-tame (hey, what could go wrong?) 200-pound bear reveled in his role, playfully wrestling with the paratroopers. Like many in the regiment, he developed a taste for beer. Aside from imbibing, Joey’s favorite activity involved protracted bathing. The Pinehurst Outlook reported that Joey relished sitting in a tub under the shower. He would object “to having his baths interrupted and growled when soldiers removed him from his ablution.”

In the fall of 1943, Joey’s regiment shipped out from Camp Mackall, forcing Joey to take a little personal time. The AWOL bear emerged from winter hibernation beneath the barracks the following March, and the newly encamped 515th regiment adopted him. His reappearance captured nationwide media attention.

Then, in July 1944, orders came directing the 515th to depart for Europe. Though Joey seemed temperamentally suited to invade France, the regiment was not permitted to bring him along and no one remaining at Camp Mackall cared to assume his custody. On the eve of their farewell, several soldiers from the 515th gathered at a Southern Pines nightspot to ponder the seemingly unsolvable dilemma of finding Joey a new home. According to longtime area resident Tony McKenzie, the soldiers, perhaps by force of numbers, persuaded several Pinehurst boys on the premises, including 17-year-old Peter Tufts (Richard’s son) and McKenzie’s brother Jack, to take Joey off their hands. Alcohol may have been involved in the transaction. Tony McKenzie recalls that the resourceful young Tufts “worked late into the night making sure the bear was safe and secure,” at the zoo at Deer Park. The nationally known “paratrooper bear” had the additional benefit of boosting zoo attendance, bringing in more visitors than ever before.

Peter Tufts and his cohorts accompanied Joey on daily unleashed romps through the park. But after a number of Pinehurst mothers complained that an untethered bear posed an unacceptable risk to the safety of neighborhood children, Joey was banished from the zoo and taken to a farm in Eastwood, where he lived until he journeyed to that big hot tub in the sky.

While Joey experienced his 15 minutes of fame, Talamore Golf Resort’s llama caddies seem to have had more legs. They’ve been making news in the golf world since the course’s opening in 1991. After learning that donkeys had been successfully employed as caddies in South America, Talamore’s owner decided to try another pack animal — the llama — in the same capacity. Stunningly, or maybe not, no golf course had used llama caddies before, and Talamore’s promotional literature hyped that novelty in its marketing. Two llamas acquired from Vermont, Billy and Dollie Llama, were trained to carry double bags over the hilly Rees Jones-designed layout. Accompanied by their handler, the llamas effortlessly, and mostly quietly, marched up Talamore’s fairways, their camel-like hooves doing no damage to the turf. Though aloof and silent when asked to read putts, Billy and Dollie never squawked about low tips, satisfying the time-honored three cardinal rules of caddying: “show up, keep up, and shut up.” Billy and Dollie Llama, golf pioneers, have rama llama ding-donged their way into the Hall of Fame.

Through no fault of their own, the llama caddies proved a double-edged sword for Talamore. With fascinated golfers frequently stopping to photograph the animals, play slowed considerably. As a result, Talamore stopped using llama caddies a decade ago but, should there ever be a sudden llama emergency, the resort still houses two of them in a pen adjacent to the 14th hole. The long-necked animals continue to be prominently displayed on the logo of Talamore hats, shirts and other paraphernalia. The resort’s “Llama Pen Bar & Grill” serves hungry and thirsty golfers at the clubhouse.

The current general manager of Mid-South Club-Talamore Golf Resort, Matt Hausser, says management is weighing a possible return of the woolly caddies. In any event, they continue to be a source of wonderment. Hausser recalls the time a few years ago when “one of our workers came up to me and asked, ‘Just how many llamas is it we have right now?’ I answered, ‘Three.’ He responded, ‘Well, believe it or not, there’s four in the pen.’ Unbeknown to us, a female llama had delivered a baby.”

In addition to Newport Dream and Shiloh, many area horses have distinguished themselves in jumping, cross-country, dressage and three-day event competitions. John Zopatti, who rides and trains horses at Gavilan Farm in Hoffman, is internationally recognized as a top dressage competitor, trainer, and coach. A United States Dressage Federation gold medalist and winner of many championships, Zopatti has ridden and trained a number of outstanding horses. He reserves a soft spot for a talented Andalusian gelding that was falling far short of his potential before Zopatti agreed to train him in February, 2015. At that time, Uwannabee WH (nicknamed “Slim”) was a nervous and tense animal — unfortunate qualities for a horse competing in the meticulously precise discipline of dressage. Zopatti brought Slim to Hoffman for the summer, and under his tutelage, the horse’s temperament dramatically improved.

“Slim began taking good, confident rides in training and then reproducing them at the shows,” says Zopatti. With Zopatti aboard, the half-Arabian soon began regularly winning dressage competitions, ultimately taking home two national titles at shows held in Raleigh in 2015.

Gavilan Farm’s owner, Will Faudree, is himself an internationally acclaimed four-star event rider. Antigua (nicknamed “Brad”) is the Australian Thoroughbred gelding Faudree rode to the Team Gold in event riding at the Pan American Games. He acknowledges that riding Brad helped “kick-start my competitive career” and marvels that in eight years of competition, “at the highest levels of the sport — including events at Rolex, Badminton, and Burghley — Brad never had a cross-country jump penalty. Now that’s one in a million!” At the venerable age of 30, Brad is enjoying his leisurely retirement at Gavilan Farm.

Foxhunting is another Sandhills activity where a good mount is a must. Brothers Jack and James Boyd founded the Southern Pines-based Moore County Hounds (MCH) in 1914, and locals have been riding to the hounds over the vast acreage of the Walthour-Moss Foundation and the Sandhills Game Lands ever since. Boasting over 20 years of experience, Lincoln Sadler, huntsman of MCH, has ridden and observed his fair share of foxhunting horses. A retired state wildlife biologist, Sadler nominated the spirited and athletic Thoroughbred he personally rode from 2011 to 2018, Rusty Trawler. Possessing the ability to effortlessly clear the highest obstacles Rusty “could jump and hang in the air like Michael Jordan,” says Sadler.

When it came to the organization’s famed pack of Penn-Marydel hounds (a strain emanating from Pennsylvania, Maryland and Delaware’s foxhunting areas), Sadler steadfastly refused to select an MVP, since the hounds are bred and trained not to stand out individually but to blend in. The Shangri-Las’ 1960s hit aside, there is no leader of the pack. “For instance,” points out Sadler, “you don’t want a hound that either outruns or does not keep up with the others.” If necessary, MCH may send a recalcitrant hound to another foxhunting pack where the animal is more likely to fit — Cool Hand Luke for hounds. The huntsman considers what he calls “biddability” (obedience) the most critical attribute for a foxhound. Greeting a stranger with a cacophony of yelps, a single command from Sadler can, like a choir director, silence the deafening chorus in a heartbeat. Just as the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame routinely chooses supergroups in addition to individual artists, so too should the Sandhills — the Moore County Hounds are in!

Dorothy Starling, the historian for Weymouth Center for the Arts and Humanities, did happen to mention that MCH’s co-founder and first master of the hunt actually expressed his choice of a favorite in writing. James Boyd, a noted author of historical novels and poetry, penned an ode in remembrance of his departed foxhound Sorrowful and delivered it to family members gathered at Weymouth on Christmas night, 1938.

Sorrowful was a ponderous dog indeed,

But nevertheless, she was the best of her breed.

The thing we realized the most was,

That whether in Heaven or whether in Hell,

There never was or will be

A dog that could hunt so well.

With apologies to the great Sorrowful and all the assembled hounds, the all-time top canine performer was the astounding Dave, a black, tan and white English setter owned by the sharpshooting husband and wife duo of Frank Butler and Annie Oakley. In 1915, Leonard Tufts hired the 55-year-old Oakley along with Butler to work at the Pinehurst Gun Club, where they taught resort guests the fundamentals of skeet and trapshooting. Female guests in particular flocked to the club seeking Oakley’s instruction. In 1916 alone, over 1,800 women visited the range. The couple would remain Pinehurst mainstays until 1922 and so would Dave, a dog with unforgettably soulful eyes that Butler had adopted in Maryland.

Oakley and Butler took part in numerous shooting exhibitions, wowing all onlookers with their rapid-fire trick shooting. A dazzling performer her entire life, Oakley was still able to smash 100 consecutive trapshooting targets at age 62. Though one suspects there would be an outcry of condemnation today, she began using Dave — a hunting dog unaffected by the sound of gunfire — in her exhibitions. Soon, she was shooting apples off the pooch’s unwavering head. If it makes card-carrying members of the ASPCA feel any better, it should be noted that Oakley used Butler’s noggin for the same purpose.

The Pinehurst Outlook’s account of a February 1917 exhibition at the Gun Club expressed amazement at what was actually a routine Oakley performance. Before a crowd of 800, she “started on coins flipped into the air — she broke marbles on the fly, shot the cigarette out of Butler’s hand, and a hole through the apple on Dave’s head.” In fact, Dave may have been a bit of a ham. Following the shot, he “threw what was left of the apple into the air, caught it in his mouth and danced about in ecstasy to exhibit the puncture.”

While Annie Oakley never grazed a hair on the obedient setter’s coat, Dave still met with a violent end, hit by a car in Leesburg, Florida, in February 1923. A heartbroken Butler dealt with the loss by authoring a book about his beloved dog, titled, The Life of Dave as Told by Himself.

Shakespeare wrote, “Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them.” An orange Carthage cat that won a national competition this summer surely falls into the final category. The feline, Jean-Clawed Van Damme, loosely named after the kickboxing actor, was the winner of Nationwide Insurance Company’s “Wackiest Pet Names” contest. Nationwide picked the winner from its database of 780,000 insured pets. In tribute to his overnight celebrity, Jean-Clawed is the final, and admittedly wackiest, Hall of Fame selection.

So, there you have it: five horses, a pair of llamas, two cats, a mule, a cow, a deer, a bear, two dogs and the Moore County Hounds — the inaugural class of the Sandhills Animals Hall of Fame. Of course, there are undoubtedly other worthy candidates. Who, by way of example, could ever forget Pee-wee, Pinehurst’s trained quail? Relax, Pee-wee, don’t get your head plume in a twist. There’s always next year. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.