How socialist politician Robert Hunter made the jump to celebrated golf course architect

By Bill Case

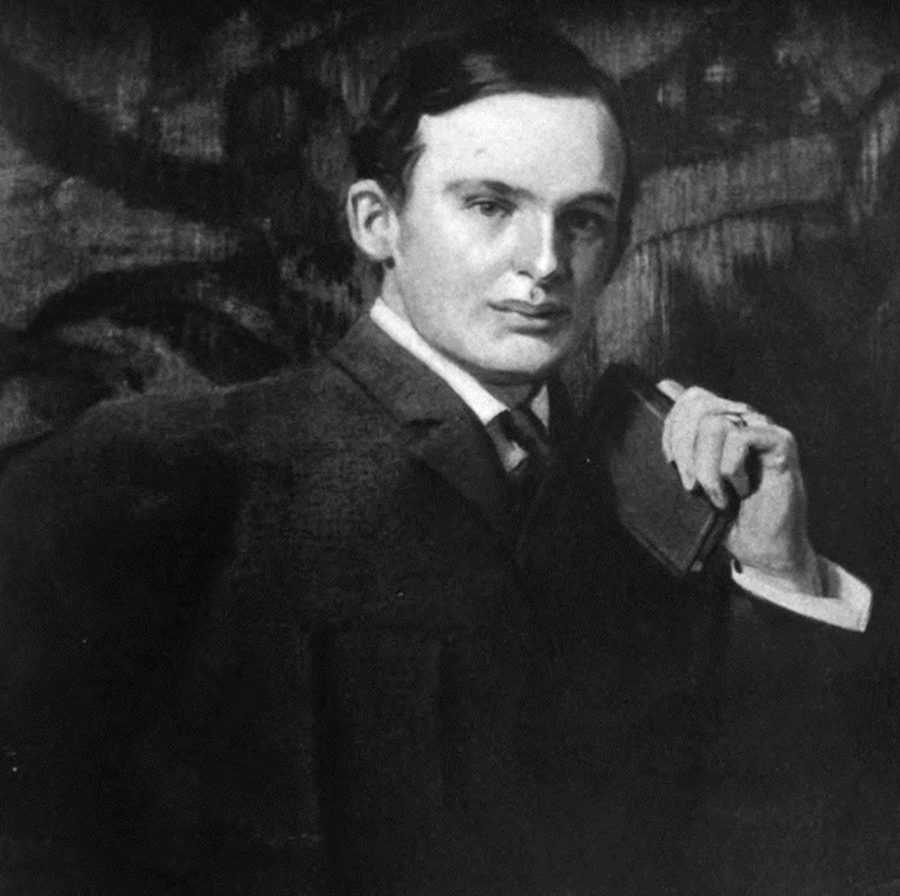

In April 1909, Robert Hunter was still a fairly new golfer, having played the game just five years. Yet the 35-year-old had already established himself as a player to be reckoned with at Wee Burn Country Club near his Connecticut home. Seeking further improvement, Hunter along with wife Caroline and family, decided to spend that April lodged at the Carolina Hotel, testing his mettle in competitive events as a new Pinehurst Country Club member.

Like so many early 20th century Pinehurst visitors, Hunter had the financial wherewithal to spend a month, if not a full season, in the Sandhills. He’d grown up in Terre Haute, Indiana, where his father operated a successful business building horse-drawn carriages. His wife, however, came from even grander opulence. This wasn’t Midwestern riches; it was New York money. Her father, Anson Phelps Stokes, had amassed a vast fortune from an array of enterprises ranging from railroads, copper mining and real estate to banking. It was Stokes who donated the trophy for the Americas Cup yacht race.

But politics set the Hunters apart from the other wealthy bluebloods — in Pinehurst and elsewhere. They joined the American Socialist Party in 1905, and Robert Hunter gained notoriety as a driving force in the party, serving on its executive committee. While the Socialist Party would have been anathema to an overwhelming majority of the well-heeled PCC members, it appears most of them welcomed the Hunters’ participation in various social activities at the club. When the couple returned to the village in January 1910 for a prolonged four month stay in Plymouth Cottage, the most important man in town, Pinehurst kingpin Leonard Tufts, made it a point to host them for dinner at The Carolina.

Hunter’s advancement into the village’s in-crowd was capped by his December 1910 admission into the Tin Whistles, Pinehurst’s pre-eminent “golfing fellowship.” While there may have been some Tin Whistles who gritted their teeth a bit before voting him in, Hunter’s engaging sense of humor — along with his rise toward the top of PCC golf ranks — tipped the scales in his favor.

It’s fair to say that, notwithstanding his party affiliation, Hunter was no radical, wild-eyed flamethrower. Born at the back end of the laissez-faire Gilded Age when ultra-capitalist “robber barons” took advantage of the lack of legal protections for workers, Hunter’s core belief that America’s working poor were being horribly treated wasn’t a heavy lift. He urged that such economic injustices could be rectified by the legislative regulation of business. The specific proposals Hunter had in mind — considered revolutionary in early 20th century America — are now codified in every jurisdiction: minimum wages, workers’ compensation, old-age pensions, limitation of the hours of work, regulations governing a safe working environment, and child labor laws. Hunter was of the firm view that the only way to obtain progressive legislation was through the political process. He and Caroline emphatically rejected the arguments of Marxists, anarchists, and others on the far left who believed democratic processes, controlled by the capitalists, were of limited usefulness, and that only confrontational actions ranging from labor strikes to outright violence could bring about meaningful change.

In 1904 Hunter’s book Poverty became a best-seller and brought national attention to the plight of workers and their families laboring under the specter of the poorhouse and starvation. To refute a commonly held perception of the well-off that the working poor were personally responsible for their desperate circumstances, Hunter produced data demonstrating that precisely the opposite was true — it was next to impossible for undernourished, overworked employees to claw their way out of the depths. “A sanitary dwelling, a sufficient supply of food and clothing, all having to do with physical well-being, is the very minimum which the laboring classes can demand,” he wrote. “The more fortunate of the laborers are but a few weeks from actual distress when the machines are stopped. Upon the unskilled masses, want is constantly pressing. As soon as employment ceases, suffering stares them in the face.”

According to Edward Brawley’s biography on Hunter, Speaking Out for America’s Poor, Hunter’s book “opened America’s eyes to the magnitude of poverty in the midst of plenty.” Poverty, wrote Brawley, made a convincing argument that “causing people, especially children, to suffer preventable poverty and ill health was not only shameful for a wealthy society but also a waste of the nation’s most valuable resources.” When Poverty failed to spur the Democratic and Republican parties to promote legislation, the Hunters cast their lot with the socialists. His writing brought Hunter significant street cred with socialist higher-ups who arranged for the author’s appointment to the party’s executive committee.

Hunter’s advocacy on behalf of the less fortunate grew out of his Indiana roots. Through his father, a charitable man in his own regard, Hunter met Eugene Debs, another Terre Haute native and the most famous socialist and influential labor leader of the late 19th century. Robert’s first encounter with Debs left an everlasting impression. “An old railroad workman joined us,” Hunter recalled. “I heard him explain to Debs that he could get a job if he could raise enough money to buy a good time-piece. Knowing that a watch was essential to a worker on the railroad, Debs immediately took out a handsome gold watch . . . unhooked it from its chain, handed it over to the man, saying ‘I care a lot about this watch . . . Keep it until you can afford to get another.’”

Though his own family’s finances were sufficient to withstand a downturn in the economy, Hunter was witness to the massive distress caused by the Panic of 1893 when falling prices resulted in countless bankruptcies. An empathetic Hunter distributed food to the hungry and went so far as to put himself on a strict diet of oatmeal. His growing concern for the poor was also influenced by the Russian author Leo Tolstoy, who believed that obedient Christians should follow Jesus’ instruction to “Sell everything you have and give it to the poor (Mark 10:21).” A young Hunter considered it his Christian duty to share with those in need everything he possessed.

Hunter’s father expected him to enter the family buggy business or embark on a legal career, but the son harbored other ideas. A light bulb went off for Robert after a chance meeting with Dr. Phillip Ayers, the secretary of the Cincinnati Board of Charities. Hunter recalled that Ayers “made my heart leap with joy by pointing out that with adequate preparation I could expect to obtain employment as a social worker.” After visiting Ayers in Cincinnati, Hunter was taken aback by the appalling conditions of the area’s slums and wanted to assist relief efforts there. When Ayers advised him to attend college first Hunter enrolled at Indiana University, graduating in 1896. By then, Ayers had moved to Chicago and was heading up the city’s Charitable Organization Society. He arranged a job for Hunter as the organizing secretary.

After observing that the teeth of children in the slums were frequently in poor condition, Hunter convinced city dentists to donate their services to those unable to pay. He also organized the first-ever municipal facility dedicated to short-term housing for vagrants, and published a study, “Tenement Conditions in Chicago,” the first of his sociological writings.

While in Chicago, Hunter resided in settlement houses, a reform phenomenon of the late 1800s where people from all segments of society came together in urban locations to find ways to alleviate area poverty. Settlement houses also became cultural destinations where famous speakers, writers, poets, public figures and educators appeared. During his stint in Chicago, Hunter lived at Hull House, operated by one of America’s pioneer social workers, Jane Addams. While in residence, he broke bread with celebrities like Clarence Darrow, Frank Lloyd Wright and John Dewey. He also spent a summer at another settlement house in London, where he met Bernard Shaw and H.G. Wells.

In 1902, Hunter moved to New York and became the head resident of the University Settlement. He led the group largely responsible for passage of the first New York state law prohibiting child labor. “It was in New York that Hunter met Graham Phelps Stokes, who like Robert, was destined to become that rarest of birds, a millionaire socialist,” wrote Brawley. The younger Stokes introduced Hunter to his sister Caroline, who was also active in social work. The two hit it off immediately and in April 1903, became engaged on the elder Stokes’ yacht, marrying a month later in Noroton, Connecticut, the Stokes’ hometown.

During the couple’s European honeymoon, Hunter visited one of his idols, Count Leo Tolstoy. The Russian confided that his attempt to give his possessions to the poor had been thwarted. The great writer’s wife refused to cooperate, maintaining that his benevolence would condemn the couple’s children to lives of ceaseless poverty. In appeasement, the author of War and Peace turned his property over to his spouse and was residing in the house as her guest. The count lamented to Hunter that this attempt at compromise had undermined his principles. Hunter described Tolstoy as “downcast, tearful and, I should say, morally wounded by his failure.”

Returning to New York, Hunter redoubled his efforts to assist the poor and live a simpler life. One frigid morning, he gave his overcoat to a shivering beggar, and then stoically did not don another throughout the winter. Rather than live in luxury, the newlyweds moved into modest quarters on Grove Street in the city’s Lower West Side (later Greenwich Village) with hopes of lending a hand toward revitalization there.

A New York newspaper reported that the Hunters had moved into “one of the vilest slums.” When it was whispered that the couple intended to give away “millions of dollars” to the poor, the rumor went viral. Hundreds formed outside their home seeking a piece of the pie — and more kept coming. For three weeks, Hunter was unable to leave the house, and it eventually forced the couple to retreat to the Stokes family enclave in Noroton.

It was during this frantic time that Hunter researched and wrote Poverty, a Herculean effort that brought him to the brink of a breakdown. His physician recommended outdoor exercise to provide a distraction, and Hunter embarked on a regimen of daily golf, despite awareness that many in his circle considered participation in the sport to be “effeminate.”

Hunter continued his deep involvement in socialist politics, writing books and lecturing. Twice he mounted runs for Connecticut political office under the socialist banner, losing both races. He sailed to Europe and attended international congresses of socialists, where he encountered Vladimir Lenin, Friedrich Engels and Benito Mussolini. President Theodore Roosevelt took notice of Poverty, and invited Hunter to a one-on-one discussion at the White House. Hunter even befriended Mark Twain.

But the amount of time Hunter was devoting to golf was beginning to rival that spent on social reform. In March, 1911, he reached the PCC club championship semifinals and then entered April’s prestigious United North and South Amateur Championship, a move specifically addressed in a tongue-in-cheek Tin Whistle bylaw that explained it was “the duty of each member to suppress the incipient conceit of any fellow member who thinks he is in line for the United North and South Amateur Championship.” Hunter surprised everyone by qualifying for match play and winning his way to the 36-hole final against the legendary Chick Evans — then at the peak of his Hall of Fame career. Hunter kept the match close during the morning round, but Evans pulled away in the afternoon to win 6 and 5. Still, it was an extraordinary feat to have reached the final given that he had only played golf for seven years.

Over the next five years, “Hunter of Wee Burn” won numerous Pinehurst events. In December 1912, he carted off the Holiday Golf Tournament’s President’s Cup, defeating former U.S. and British Amateur champion Walter Travis in the final match. He beat the great Travis again in a scintillating extra-hole match to win Pinehurst’s Mid-April Tournament in 1914, and successfully defended that championship the next two years. Hunter fashioned a second excellent performance in the 1915 North and South championship by reaching the semifinals, and he won the 54-hole medal play Tin Whistles championships of 1914 and ’15.

In January 1913, the Hunters purchased Mystic Cottage, which, according to the Pinehurst Outlook, was “the largest and most attractive of the winter homes here.” The couple hosted dinners in their spacious home with distinguished guests like Leonard Tufts and Donald Ross. It did not go unnoticed that the millionaire socialist, having once craved a Spartan existence, was increasingly living a life of opulence. Some thought the man a hypocrite, a charge Hunter never satisfactorily rebutted. His encounter with Tolstoy (recounted in his 1919 book Why We Fail as Christians) and the adverse public reaction to his own attempt to live modestly in New York may have persuaded him that self-denial was not all it was cracked up to be.

In any event, his disenchantment with his fellow socialists was growing. A majority of party leaders advocated labor strikes and other confrontational actions that moderate socialists like Hunter thought wrongheaded. This disagreement over tactics became intractable and led to his resignation from the Executive Committee in 1912. His disaffection was further exacerbated when the party refused to support America’s 1917 entry into World War I.

Hunter approved of the war declaration, reasoning that the conduct of a militaristic and conquest-driven Germany threatened the rights of working people in all democratic countries. In protest, the Hunters and thousands of former party supporters who likewise favored the war fled socialist ranks in droves. The party nearly disintegrated and was never again a major factor on the American political scene.

Increasingly regarded by many colleagues on the left as a pariah, Hunter began pursuing another outlet for his considerable energies — golf architecture. He wrote that his interest in the subject led him “abroad in the summer of 1912 for a six months’ study of the structure and upkeep of the championship courses of Great Britain.” The courses he visited included the Old Course at St. Andrews, Prestwick, Muirfield and Hoylake, all “by the sea in links-land.” As the demand for new golf courses in America was rapidly escalating, a self-taught crash course in golf architecture at the game’s birthplace could provide enough bona fides to start a course design business.

But it was not going to happen in Pinehurst, where Donald Ross monopolized commissions for golf courses up and down the Eastern Seaboard. In 1917, the Hunters pulled up stakes from their Connecticut and Pinehurst homes and relocated to Berkeley, California, where he filled a teaching position at the University of California until 1922. While relishing his new environment, Hunter admitted missing Pinehurst’s golf courses, bemoaning in a letter to a friend, “There is absolutely none where I am now living — unless I am to consider the local country club, which resembles one of the sand clay roads of Moore County.”

However, Northern California’s lack of courses also provided an opportunity. When Berkeley locals decided to build a new course in 1920, Hunter was named chairman of the fledgling club’s greens committee. Soon, he had drawn up a set of complete plans for the course. Berkeley Country Club had already hired the well-established Willie Watson as course architect, but Hunter’s routing left little for Watson to do. He basically rubber-stamped Hunter’s design work. Hunter also oversaw the course’s construction and today, the club acknowledges he deserves the lion’s share of credit for the design.

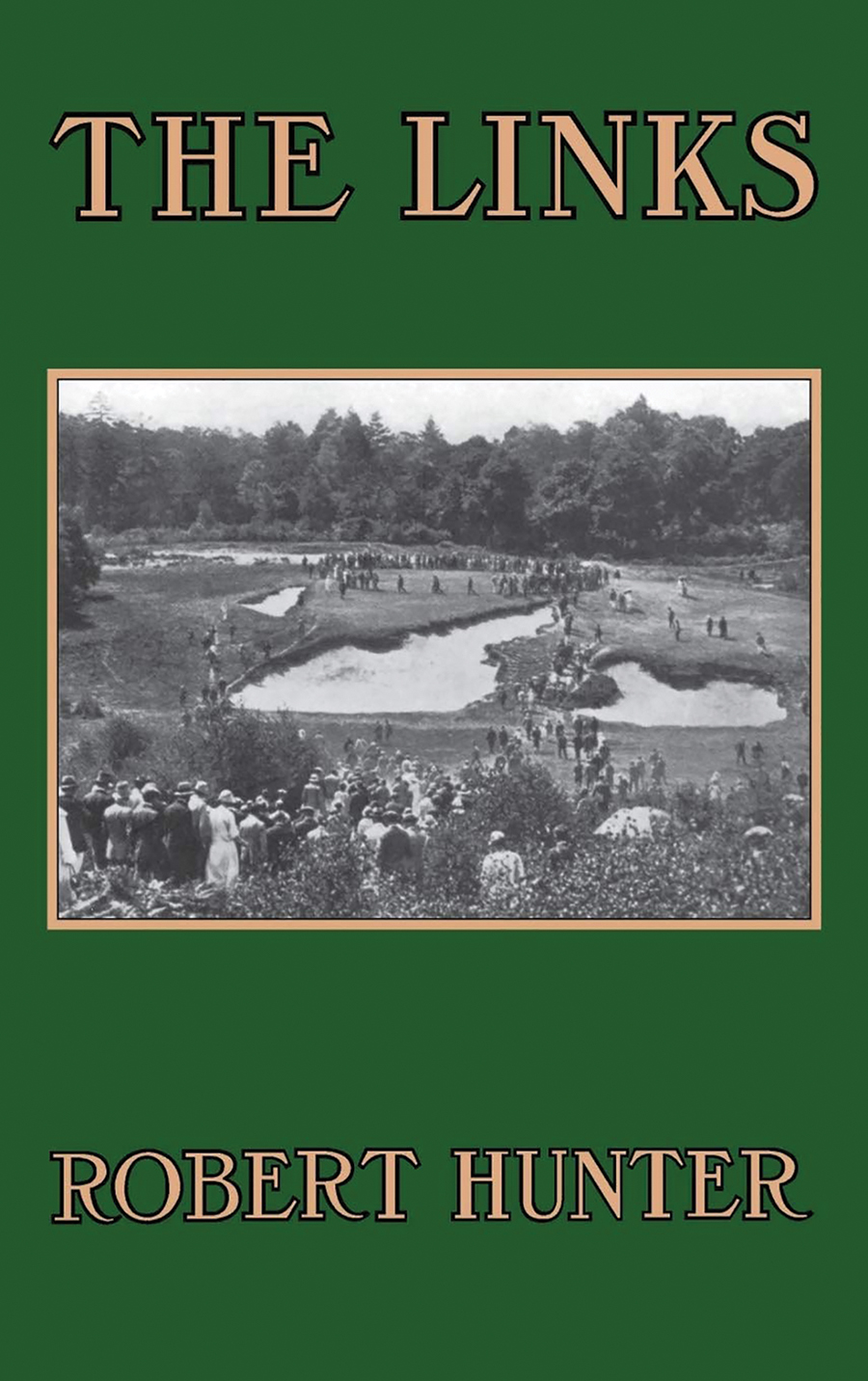

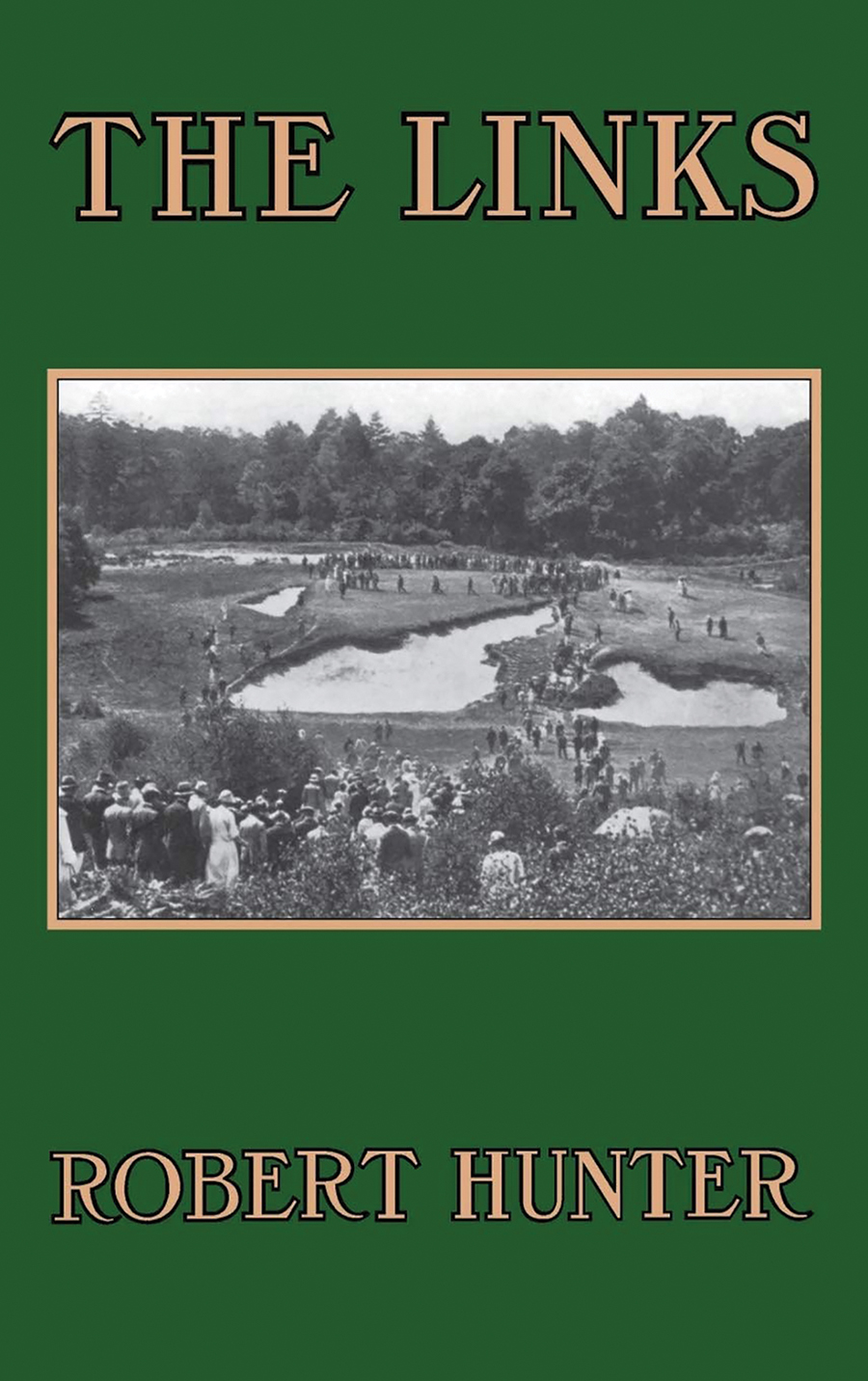

After a fire destroyed his Berkeley home, Hunter moved to Pebble Beach, hoping his work at Berkeley CC would create sufficient splash on the Monterey Peninsula to result in further design commissions. It did not. How could he broadcast his course design chops and simultaneously prove he was no dilettante in the field? The same way he had cemented his reputation for reform advocacy — by writing a book. Published in 1926, The Links became an authoritative reference bible for every phase of golf course design and construction. It’s chock-full of the author’s philosophy regarding everything from hiring a designer and acquiring land to the placement, shape and contours of hazards, bunkers, and greens. Noted designer Bill Coore still consults Hunter’s book and says that it “became a cornerstone in my personal golf architecture education and a bond in my partnership with Ben Crenshaw, who I learned had begun studying The Links at approximately the same time I did.”

The book came to the attention of the renowned British golf architect Alister MacKenzie, who was wowed by Hunter’s grasp of the innumerable details of course design, calling “it by far the best book on golf architecture ever written.” So, when Hunter proposed that he and MacKenzie build courses together in California, the Yorkshireman, who had never been to the West Coast, listened and agreed. Hunter expected the two would find themselves deluged with commissions. He was correct. Requests for work to be performed by the firm of MacKenzie and Hunter poured in.

In August 1926, the new partners entered into a contract to design a course for the Meadow Club in the San Francisco Bay area. This was followed by projects for the California Golf Club of San Francisco; Woodside Country Club near Stanford University; Green Hills Country Club; Northwood Golf Club; Pasatiempo Golf Club; and the Valley Club at Montecito. MacKenzie and Hunter updated the Pebble Beach links in preparation for the club’s hosting of the 1929 U.S. Amateur. To some extent, Hunter’s working relationship with MacKenzie mirrored the one he had established with Willie Watson at Berkeley. The more flamboyant MacKenzie was always the name architect while Hunter promoted him and managed the details on the ground. He seemed content to play the role of second banana in the relationship, though MacKenzie fully recognized Hunter’s ingenuous contributions. Regarding their work at the Valley Club at Montecito, an appreciative MacKenzie lauded his partner for introducing “a new machine, a Caterpillar tractor with bulldozer equipment, to remove the large rocks and boulders. He thus saved thousands of dollars in explosives and manual labor.”

But the partnership’s tour de force was its work in 1928 designing and building the incomparable Cypress Point Club, an oceanside course so beautiful it’s often referred to as golf’s Sistine Chapel. Golf historian and architect Geoff Shackleford calls the course “the most stunning creation in the history of golf course architecture.” Hunter, a local, was again the man responsible for overseeing the progress of daily construction. Also involved was son Robert Jr., who headed up the American Golf Course Construction Company.

It is too late to unravel the individual contributions Hunter and MacKenzie each made that resulted in the finished product at Cypress Point. Nonetheless, it is clear that Hunter was no mere sidekick and deserves far greater credit than he ever received for Cypress and the partners’ other wonderful California courses. Their association lasted until 1929, when the Great Depression tanked most all golf construction projects.

With the advent of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal in the early 1930s, Hunter ping-ponged back into the analysis of the nation’s affairs. This time he had a far different spin on things. Despite the fact that the president’s leadership resulted in the enactment of progressive legislation, which he would have undoubtedly supported in his socialist days, Hunter was alarmed at what he perceived to be Roosevelt’s dictatorial tendencies. He viewed the president as a profligate spender whose economic policies were destined to result in an inflationary upheaval that would ultimately culminate in revolution.

Hunter pointed out that Lenin had hijacked Russia’s progressive movement and imposed a brutal dictatorship under similar economic circumstances. In 1940, he encapsulated his dire warnings (which, of course, proved to be greatly overblown) with another book, Revolution: Why, How, and When?, that was favorably received by those Republicans who despised Roosevelt, then running for his third term. The former socialist also served as an adviser to Republican candidate Wendell Willkie during the latter’s unsuccessful campaign for the presidency against Roosevelt in 1940.

Hunter would pass away two years later.

Most biographers tend to discount Hunter’s rants against the New Deal and Roosevelt, focusing instead on his earlier social reform efforts and authorship of Poverty. Of course the world of golf remembers another Hunter book, The Links. But the ripple effects of his contributions to the game reach beyond his writings. If he had not induced Alister MacKenzie to come to California, Cypress Point might never have been built in the glorious manner it was. And if there was no Cypress Point, Bobby Jones would never have chanced to play the course in 1929, nor would he have engaged MacKenzie in the design of Augusta National Golf Club.

Pinehurst had its role to play. It’s where Hunter’s interest in golf course architecture was first cultivated, and his acquaintance with fellow Tin Whistle Donald Ross (whose layouts Hunter revered) undoubtedly gave him meaningful exposure to the art and science of design. While his impact may have been easy to overlook, his legacy is astonishing in its scope. PS