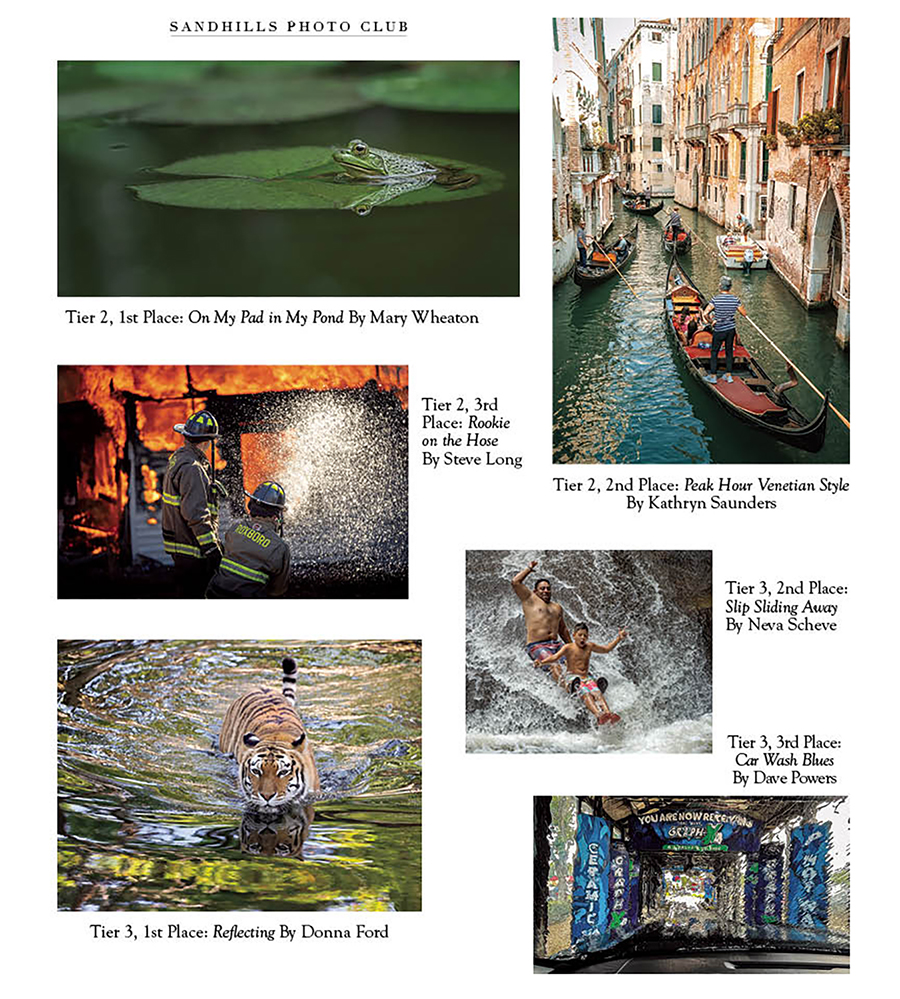

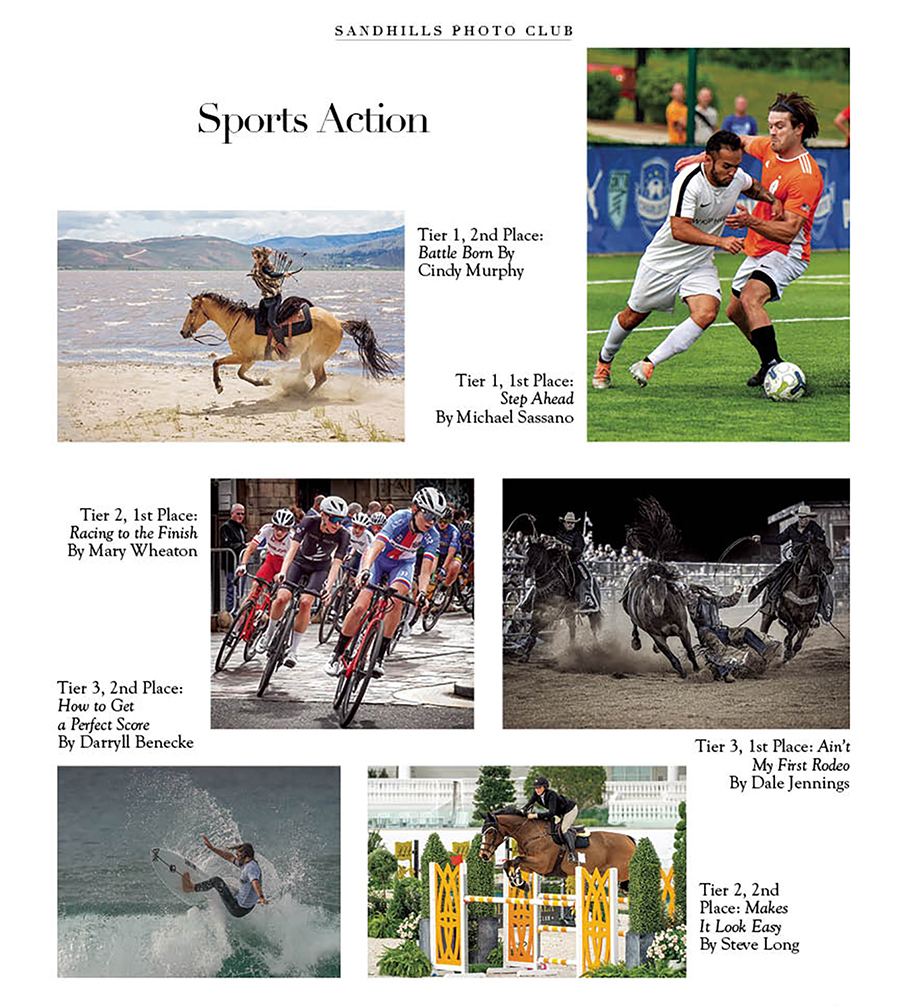

Party Animals

N.C. Zoo celebrates five decades

By Jim Moriarty

Photographs Courtesy of N.C. Zoo

Feature Photo: Southern White Rhinos (from left to right: Bonnie, Abby and Nandi) and Fringe-Eared Oryx in background

It began with Sonny Jurgensen, Tort and Retort. None of them moved very fast, but all of them played significant roles in the birth of the North Carolina Zoo 50 years ago.

The zoo, built initially on 1,371 acres in Randolph County near Asheboro, is the largest natural habitat zoo in the world. It entertained over a million visitors last year, including nearly 90,000 students who attended free of charge. The formal celebration will be on Aug. 2, the day the interim facility was officially dedicated in 1974. Among the many promotions staged throughout the year will be the recognition, probably sometime in June or July, of the zoo’s 30 millionth guest, who will be showered with a lifetime membership, a Zoofari (an open-air trip through the Watani Grasslands), and every manner of zoological swag known to man.

Left to Right: Giraffe (Turbo), African Elephant (C’sar), Red Wolves (from left to right: Catawba and Pearl), American Alligators (from left to right: Liv and Gatorboy)

The seed money for the zoo came, in part, from a series of four preseason football games that raised money for the feasibility study to determine the location of the zoo. The first of those games was on Aug. 19, 1967. The Washington Redskins (now Commanders, though that’s likely to change) were led by their quarterback, Jurgensen, a Wilmington native, and linebacker Chris Hanburger, who was born at Fort Bragg (now Liberty) and attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The Giants had a Carolina connection of their own: Darrell Dess, a guard/tackle who had attended N.C. State University. The game was played at night, the first such event, at what was then called Carter Stadium in Raleigh. Washington won 31-13 in front of 33,525 who paid six bucks apiece to attend.

Left to Right: Southern White Rhinos (from left to right: Linda and Jojo), Southern White Rhinos (from left to right: Linda and Jojo), Galapagos Tortoise (Retort), Galapagos Tortoise (Retort)

The location that was eventually settled on for the zoo was known as the Purgatory Mountain site, named, according to legend, for the fires from the moonshine stills visible at night. Randolph County donated the land, the state legislature earmarked $2 million for the project, and hiring began.

The interim zoo, today nothing more than a staging and construction area, became home to the first animals, two endangered Galapagos tortoises named Tort and Retort, who were sent to other zoos long ago for propagation, one of the zoo’s foundational purposes. “The interim zoo was chain link, that’s all it was,” says Diane Villa, the zoo’s director of communications and marketing. “But that’s not what we were going for. What sets our zoo apart from other zoos is the original vision for what they wanted it to be. They wanted it to be good for the animals.” Its creation marked a turning point from concrete, fenced facilities to the creation of environments as close to the animal’s natural habitat as possible.

Left to Right: African Elephants (from left to right: C’sar, Batir, Rafiki, Nekhanda and Tonga), African Lion (Mekita), American Bison (Calf), Red River Hog (Patience)

Bill Parker was one of the facility’s earliest zookeepers. A graduate of Pfeiffer University (Pfeiffer College at the time), he began in ’74 and retired six years ago this September. “When I started there were probably fewer than double digits of permanent employees, mostly in administration,” he says. “They started acquiring animals in the late summer and early fall of ’74.” And it was definitely learn as you go.

By the end of the decade he was working in animal care. “I was on the African grasslands, at the time we called it the African Plains,” he says. “We were riding on the back of a truck and we had an antelope, called a nyala, that was breach birth. So we called out the vets and we started doing what we could to help the animal deliver, but it looked like it wasn’t going to survive. So, in the back of the truck, the vet did an emergency C-section and pulled the calf out. The lady I was working with — her name was Nancy Lou Gay Kiessler — who was training me to be a keeper, immediately took the calf out of the vet’s hands, wiped the mucous off its snout, and she put the snout in her mouth and started giving it resuscitation. I thought, ‘Boy, if I’m ever called to do that, I don’t know if I could.’ What it demonstrated to me was the level of care and compassion she had for that group of animals, and that calf survived.”

Left to Right: Ocelot (Inca) Chimpanzee (Obi), Fringe-Eared Oryx, Zebra (Spirit), Grizzly (Ronan)

Part of the zoo’s commitment in helping to restore populations of endangered species involves transporting animals to facilitate breeding recommendations in a program implemented by zoos and aquariums called the Species Survival Plan. These days the animals are shipped FedEx, but Goldston has done it driving down I-85. “My first transport was in ’99. We had a recommendation to move our male gorilla to a zoo in Atlanta. Myself and another keeper, I think we were somewhere in South Carolina, we needed to stop to refuel. It was one of those combo stations where it’s a Wendy’s on one side and a fuel stop on the other. So I’m standing in line waiting to get our food and I’m just reeking with gorilla musk. People are sniffing and turning around. ‘Where’s it coming from? Who is it?’ We just sort of cracked up.”

Left to Right: Elephant (Tonga) & Rhinos (from left to right: Nandi and Bonnie), Red Wolf (Warrior), Western Lowland Gorilla (Hadari), Desert Dome

If the early days had its challenges, over five decades the zoo has grown, gazelle-like, by leaps and bounds. Today it manages 2,805 acres and broke ground on an Asia region in August of ’22 that will feature tigers, Komodo dragons and king cobras, to name a few species, when it opens in two years. There are currently 305 permanent state employees with a staff that expands to roughly 700 during the highest traffic months. The zoo has three full-time vets on staff and a number of vet techs. “They work on everything from Madagascar hissing cockroaches to African elephants and everything in between,” says Villa. The zoo won the 2021 World Association of Zoos and Aquariums sustainability award.

A monitoring and reporting tool called SMART, developed by the North Carolina zoo in collaboration with the Wildlife Conservation Society and several other zoos, is being used in over 80 countries to track animals and combat poaching. “A lot of animals are in trouble. African lions, African elephants, vultures. One of our signature programs here is vulture tracking,” says Villa. “They’re part of the circle of life. African vultures are one of the steepest declining birds in the world. One of our scientists, Dr. Corinne Kendall, is one of the leading vulture experts. If there was one thing that we try to let people know, it’s that just by coming to the zoo, your admission price helps support our conservation efforts. We’re trying to be a leader for our guests.” Man and animal alike. PS

M

M

One chilly

One chilly