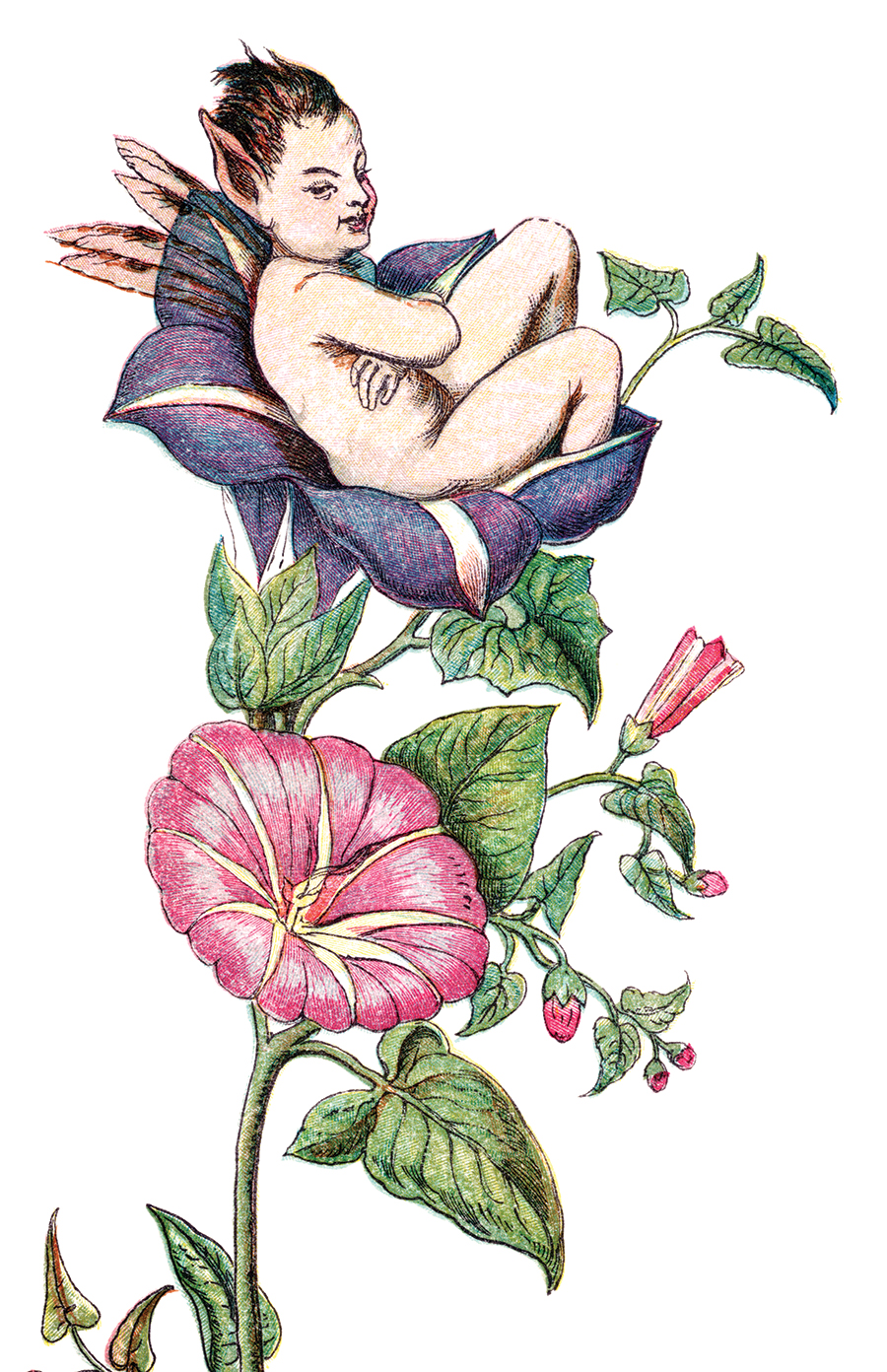

Those with “the Sight” claim there are wee folk among us. Do you believe?

By John Hood • Illustration by Harry Blair

That rock in the river was a big one. Big enough to sit on. That’s what the woman did, in fact, while her husband spent the afternoon fishing upstream. She waded out to the rock, found a comfortable seat, and took out a book to read. What happened next was like something out of a book — but not the one she was reading.

Hearing footsteps and voices, the woman glanced up and saw two boys cavorting along a trail, their distracted father trudging along behind. As the boys approached the water’s edge, something else entered her field of vision. “It started coming up the river,” she later recalled.

What was “it”? A “pale-skinned, water-logged-looking” creature, she said, “with black hair and sharp, serrated teeth showing in a smile.” Paying no attention to the woman perched on the rock, it “focused on the boys” and moved rapidly through the water toward them.

She wasn’t the only one who saw it. The boys did, too. They picked up sticks and pointed them at the mysterious swimmer. The woman never found out if their makeshift weapons would have done any good. Although apparently unable to see the creature that was now just a few feet away from his boys, the father nevertheless decided they were playing too close to the water and ushered them back to the trail.

That the boys were briefly in peril, though, the woman never doubted. “It watched them move up the trail away with a creepy look on its face,” she said, “and then moved on upriver out of sight.”

Maybe you think you know what was really in that river. A bullfrog. A bottom-feeder. A bumpy log converted into something sinister by an overactive imagination. But the woman in question is convinced she saw a fairy. Just a few years ago. Right here in North Carolina.

It’s not our state’s first fairy sighting. It won’t be the last. Oh, it’s easy to scoff at those who claim to see wee folk wading in rivers or slinking through forests or dancing on hilltops. How childish. How backward. How unscientific. Well, sure. But I bet you know someone who still carries a lucky charm or wears a lucky sweatshirt whenever the Wolfpack play the Tar Heels. I bet you know someone who watches Ancient Aliens or Ghost Hunters, hits up psychics for advice or thinks Bigfoot just might really be out there somewhere, camera-shy but furtively flattered.

By the way, what’s your sign?

Generations ago, all the smart people thought universal schooling would disabuse the masses of such fanciful superstitions. They thought the relentless march of science would muscle old faiths and folk traditions aside — confining them, converting them into historical curiosities. “Rationalization and intellectualization,” the sociologist Max Weber famously predicted a century ago, would bring “the disenchantment of the world.”

Then a great many of these same smart people went out and got their palms read. Or sat in seances. Just for the experience, you know.

The magical, the paranormal, the supernatural are not so easily banished. According to a recent Harris Poll, 42 percent of us believe in ghosts, 36 percent in UFOs, 29 percent in astrology and 26 percent in witches. Fairies — by which I mean the broad swath of legendary little people, not just tiny Tinker Bells with translucent wings — rarely get included in American polls. But surveys in other countries find significant minorities still believe in fairies. In some places, such as Iceland, believers form a majority.

Among the believers is the woman I mentioned earlier. I wish I could tell you more about her and the fairy encounter she claimed to witness from that big rock. Unfortunately, I can’t even tell you her name. Anonymity was the promise made by folklorist Simon Young in 2014 when he began soliciting first-person accounts of fairy sightings. Published four years later as The Fairy Census, Young’s research spans hundreds of stories from around the world — including several from our state.

I can tell you the woman says it wasn’t her first sighting. “I have seen them since childhood, different ones,” she told Young. “My granny from Ireland says I have ‘the Sight’ like her.” The woman describes fairies as “beings from another world” that can have good or bad intentions. “I was always taught to never talk to them or let them know I see them.”

I can also say that, if you believe her story and hope to see your own fairy one day, there are plenty of places in our state worth exploring. While researching my new historical-fantasy novel Mountain Folk, largely set in North Carolina during the American Revolution, I learned a great deal about the fairy lore of our ancestors. Some of it developed locally, tied to specific Carolina landmarks. Other beliefs were brought here from afar — from the British Isles, from Northern Europe and the Mediterranean world, from West Africa. It turns out that almost all cultures have stories of wee folk. Accounts vary, of course, but a surprising number of them converge in key details: creatures two to three feet tall, invisible to most if they wish to be, infused with magic, attuned with nature, prone to pranks but also willing to trade favors for something they covet.

Based on the woman’s description, for example, you might find her rocky seat in some Piedmont river or mountain stream. The original inhabitants of those parts of North Carolina often told tales of such creatures. Among the Cherokee, for example, they were called the yunwi amayine hi, or “water dwellers,” and had the power to boost fish catches and promote healing.

In one story, a water dweller disguises herself as human to attend a dance. Smitten by her charms, a Cherokee man follows her to a riverbank and professes his love. He must be persuasive, for she agrees to become his wife. Eyes sparkling, she dives in the river and beckons him to follow. “It is really only a road,” she says. He takes a deep breath and leaps. Finding a wondrous world hidden beneath the river, he lives there happily as her husband. Later, when he leaves to visit his parents, they turn out to be long since dead. Generations of Cherokee live and die during the few years he lives among the water-dwellers.

Alternatively, maybe what our eyewitness saw was not a diminutive humanoid from native folklore but something scalier. The place where the Haw and Deep rivers converge in Chatham County to form the Cape Fear is nicknamed Mermaid Point. Just before the Revolutionary War, a man named Ambrose Ramsey ran a tavern nearby. When the locals left Ramsey’s tavern late at night to stumble home, they’d pass a sandbar. On numerous occasions, they spotted small figures luxuriating there in the moonlight. Figures with the heads, arms and torsos of beautiful women and the lateral lines and shiny tails of a fish. If the patrons were quiet and kept to the shadows, they could watch the mermaids laugh, play, sing and comb their long hair. But if the men tried to speak to them, the fairies would disappear into the water.

Rivers are hardly North Carolina’s only sites for fairy lore. Another folk from Cherokee legend, the Nunnehi, are associated with such locations as Pilot Mountain (both the famous monadnock in Surry County and a lesser-known peak near Hendersonville) and the modern town of Franklin, where the Nunnehi were said to have helped defeat a Creek invasion and, much later, a raid by Union soldiers. On the other side of the state, in and around the Great Dismal Swamp, the mythology of Iroquois and Algonquin speakers mingled with European and African-American legends to produce a rich folklore of eerie lights, dark shapes and magical creatures.

Moreover, as the Fairy Census reminds us, our sightings aren’t limited to old tales preserved in old books. They still happen. A 30-something woman reported “staring at the foot of the bed at the light coming in through a large window when I saw a fairy suddenly appear on one side of the room and fly across the bed toward the window.” She described the creature as brown-haired and gaunt, about three-feet tall with sharp features “not very pleasant to look at.”

The woman wasn’t alone. But her husband, lying next to her, never saw the fairy. “I think it is strange that I had this experience in my house in suburban North Carolina, of all places,” she said.

Another North Carolinian described an encounter she had in her youth with a fairy “about two to three feet tall, dressed entirely in red, with a solid red face, tiny white horns on the top of his head, and with a red, pointed tail.” He was standing next to the stump of a tree that had been his home until it was felled during the construction of the girl’s house. She ran to get her parents. But they couldn’t see it.

The more you study both folklore and modern-day sightings, the more you come to appreciate the commonalities. I decided to include several in Mountain Folk, such as the extreme time difference between fairy realms and the human world, the link between fairies and nature and the idea that only those rare humans possessing “the Sight” can pierce fairy disguises.

Do such commonalities suggest fairy traditions aren’t pristine, that they develop over time through cross-cultural exchange? Or that people claiming to see fairies are just mashing up distant memories of bedtime stories with drowsy daydreams and optical illusions? Could be.

There are many explanations for fairy belief. For some, it’s reassuring to believe that good and bad events aren’t just random. That powerful forces are at work, magical forces to be tapped or propitiated. For others, fairy belief is about rediscovering a sense of wonder — about reenchanting the world, as Weber might say, instead of settling for a cold, clockwork version.

That’s how some of your fellow North Carolinians feel, anyway. Whether out exploring their state’s natural beauty or just puttering around the neighborhood, they keep their minds open along with their eyes. They suspend their disbelief. They dare to hope that something utterly fantastic will happen. That something utterly fantastic can happen.

After all, it’s happened before. Or so they’ve heard. PS

John Hood is a Raleigh-based writer and the author of the historical-fantasy novel Mountain Folk (Defiance Press, 2021).