Pinehurst’s Fownes Family left an enduring legacy in golf

By Bill Case

When Bill Fownes faced George Dunlap Jr. on Dec. 31, 1929, in the final match of Pinehurst’s Mid-Winter Tournament, he was a decade past his golfing prime. He had won the 1910 U.S. Amateur Championship and remained a top-ranked golfer for another dozen years — good enough to play on two Walker Cup teams, captaining the U.S. side in the 1922 matches. He won numerous championships in his home state of Pennsylvania, including four state amateur titles. By contrast, the 20-year-old Dunlap, already a four-time Mid-Winter champion, was emerging as one of America’s best amateurs. The Princeton junior would win the 1933 U.S. Amateur, and seven United North and South Amateur titles.

Time had contributed to Bill Fownes’ golfing decline — he was by then 52 — and health issues were dogging him. In 1926, he suffered a heart attack at his Pinehurst winter home after a round. It is unlikely he would have survived but for the quick actions of his caddie, who had been waiting outside to be paid. When Fownes failed to reappear, the caddie rushed inside and found him unconscious next to the doorway.

Notwithstanding the difference in their ages, Fownes and Dunlap shared much in common. Both lived in Pinehurst during the winter season and competed at amateur golf’s highest level. Fownes’ metallurgical engineering degree from Massachusetts Institute of Technology equated with Dunlap’s Ivy League education. Both were sons of amazingly successful and wealthy fathers. George’s father founded the renowned book publishing company Grosset and Dunlap, while Bill’s dad, Pittsburgher Henry C. (H.C.) Fownes, made his millions acquiring and operating an array of enterprises associated with iron, steelmaking, and oil. Furthermore, Bill, George Jr. and their fathers were all active members of The Tin Whistles, Pinehurst’s pre-eminent male golf society.

But the Fowneses had accomplished something that no other family could match. It was H.C. who in 1903 founded Pittsburgh’s Oakmont Country Club, designed its epic course, and fashioned it into the most demanding test in championship golf. Bill then took charge of pushing the penal nature of the course to the max. For decades, he would roam Oakmont’s grounds, plotting the placement of additional harrowing bunkers. The younger Fownes believed that “the charm of the game lies in its difficulties.” He explained his course design philosophy with the pithy aphorism, “A shot poorly played should be a shot irrevocably lost.”

Few of the several hundred spectators gathered at the first tee of Course No. 2 to watch the Mid-Winter’s championship match gave Fownes much of a chance against young Dunlap. The older man began the match unsteadily, losing the first two holes. He righted himself and stood only 1 down as the match reached the eighth green, where Dunlap’s ball rested 4 feet from the pin while Fownes’ checked up nearer the hole. According to the Pinehurst Outlook, “the Princeton golfer slightly hooked his putt and knocked Fownes’ ball into the hole.” This astounding break brought Fownes even with the nonplussed Dunlap.

Thereafter, the battle was nip-and-tuck with neither player gaining better than a 1-up advantage. The match stood all square on the 18th. Dunlap misplayed his approach, and suddenly Fownes faced a 5-foot putt to win the match. To convert it, Fownes’ ball needed to barely miss Dunlap’s, which was partially blocking the line. He nursed the tricky slider past the stymie and into the cup for the upset victory. The Outlook reported it as “one of the most stirring finishes ever seen in a Pinehurst tournament.”

The victory was Fownes’ last hurrah in competitive golf. Within months, he suffered a second debilitating heart attack. More seizures followed and he would lie bedridden for six weeks. Though Fownes would survive the scare, he curtailed his business activities and ceased playing golf altogether.

W.C. Fownes’ fragile health in 1930 contrasted markedly from that of his wiry and agile father, H.C., who at 74 still golfed daily and, according to the younger Fownes, “seemed to have almost unlimited stamina and endurance.” H.C. brought this same gusto to driving an automobile. He loved fast cars and motored his flashy Duesenberg from Pittsburgh to Pinehurst with pedal to the metal over the rutted dirt roads of the era.

This zest extended to his social life. A round of golf in Pinehurst was incomplete until he and his Tin Whistles playing partners sipped drinks at the home H.C. built on East Village Green Road in 1914. During the season, eight to 10 visitors usually lodged in its spacious quarters. A widower following his wife, Mary’s, death in 1906, the convivial entrepreneur was usually the last man to depart a party or a card game. H.C. favored bridge and poker, pastimes likewise enjoyed by Bill.

Father and son shared much more. According to Bill, they “went through the bicycling craze together,” and regularly played tennis. “So that from early boyhood . . . and because of (our) close association, I was frequently classed as his brother instead of his son; much to my father’s amusement and gratification.” The son’s premature baldness no doubt contributed to this misapprehension.

The men were inseparable business associates. Two years after his 1898 graduation from MIT, Bill joined his father, and extended family, in operation of their various enterprises. These included an iron casting foundry in Pittsburgh, a modern blast furnace in Midland, Pennsylvania, coal reserves and coke oven near Brownsville, Pennsylvania, and the Standard Seamless Tube Company. In 1929, the Fowneses diversified this portfolio, founding the Shamrock Oil & Gas Company. Bill served as his father’s alter ego in managing these undertakings though “no major decisions were made without his (H.C.’s) guidance and advice which in the last analysis was the determining factor.”

Most of all, the Fowneses, père and fils, shared a passionate love of golf. Though not in the same class as his son, H.C. became an exceptional player despite starting the game in 1898 at the age of 42. By 1901, he was competing in the U.S. Amateur, even winning three matches in the 1905 championship before his elimination. He captured The Tin Whistles club championship of 1906.

H.C.’s greatest playing achievement was winning Pinehurst’s 1918 Spring Tournament at age 62. He defeated son C.B. “Chick” Fownes (Bill’s brother) in the final match. Chick was a fine player despite suffering from palsy. “He is the greatest putter in the world,” marveled Walter J. Travis, America’s best player in the early 19th century, and noted for his own putting chops. The Outlook observed that the Spring Tournament’s all-Fownes final meant that, “not one man (of the 217 in the field) could beat a Fownes. Not one.”

While H.C., W.C., and C.B. may have cornered the initials market, they weren’t the only distinguished Fownes golfers of the period. H.C.’s daughter Mary took home the championship trophy at the 1909 Women’s United North and South Championship, while his niece Sarah finished runner-up in 1919 and 1922.

The family’s many fine golfers might never have chanced to take up the game absent a freak injury H.C. sustained in 1896 that was followed by a botched medical diagnosis. Then 39, H.C. sought to make a patch for a bicycle tire by heating it with a hot wire while neglecting to wear any eye protection. After completing the repair, he became aware of a black spot interfering with his vision. His physician grimly advised it was the result of arteriosclerosis and that H.C. could expect to live at best another two to three years. “This information, of course, was very depressing,” said Bill, displaying something of a gift for understatement. As a result, H.C. ceased his immersion in business ventures and “started traveling about the country seeking relaxation.” One recreational outlet was golf, which he took up at the suggestion of friend and fellow steel titan Andrew Carnegie.

H.C. eventually learned from a specialist that his eye’s blind spot was not, in fact, a death sentence. It had come from the subjection of his eye to the blinding light and heat caused by the tire repair. Given a new lease on life, he returned to work, but now balanced it with time for leisure — mostly golf. He began playing at Pittsburgh Field Club, a small athletic facility located in what is now Fox Chapel. Dissatisfied with the club’s rudimentary course, H.C. helped start Highland Country Club, which featured a nine-hole, 2000-yard layout. It was the venue where H.C. introduced many family members to the game. In fact, four Fowneses playing out of Highland (himself, his two sons, and brother William Clark Fownes, for whom W.C., Jr. was named) won the 1902 Pittsburgh district team championship.

With the game’s popularity on the rise, H.C. decided Pittsburgh deserved a course of challenge and stature. When he learned that farmland above the Allegheny River in Oakmont might provide a suitable location, he rounded up shareholders to buy the property and build a new course. To retain control, H.C. purchased the majority of the shares himself.

Who should design this new behemoth? The self-confident H.C. just happened to have someone in mind — himself. Fownes fashioned a virtually treeless, bunker-strewn course of architectural brilliance containing unique features like the notorious Church Pews bunker between the third and fourth fairways. The humps, moguls and terrorizing speed of Oakmont’s greens would prove humbling to the best putters. In an era when the longest courses topped out at 6,000 yards, Oakmont’s distance at its 1904 opening stretched to a hitherto unimaginable 6,600 yards, with a par of 80.

H.C. also assumed the role of Oakmont Country Club’s president. He adamantly rejected any favoritism toward wealthier, more prominent members. Bill wrote that his father “hated all pretense or show,” and was insistent “that every member in the club was entitled to equal rights.” The club welcomed female members, a rarity during that period. H.C. also took pains to recruit excellent golfers — three members, including Bill, would win the U.S. Amateur.

Bill’s victory in the 1910 championship at the Country Club in Brookline, Massachusetts, featured a sensational semifinal match with legendary Chick Evans. Down two holes with three to play, all seemed lost for 33-year-old Fownes after he bunkered his tee shot on the par-3 16th. But when Bill holed a sizable putt for par and Evans three-putted, the deficit was cut in half. Fownes’ birdie on 17 squared the match, and after the frustrated Evans three-putted the final hole, the resilient Fownes escaped with a win. His 4 and 3 defeat of Warren Wood in the final proved far easier.

Throughout the first quarter of the 20th century, W.C. Fownes remained a mainstay in the U.S. Amateur. A four-time semifinalist, he qualified for the event 19 times in 25 years. His last notable performance came in 1919, held fittingly at Oakmont. He reached the semis before bowing to Bobby Jones.

The honing of his formidable skill had been enhanced in tournaments and exhibitions during Pinehurst winters. The Fownes family’s annual migrations to Pinehurst began around the time that H.C. started the Oakmont project. At first, only H.C. and golfing sons Bill and Chick made the excursion, bunking at the Carolina or the Holly. The Tin Whistles provided an ideal golf and social outlet for the men. Bill and his dad would both become presidents of the organization with H.C. serving in that capacity three times.

In 1908, Mary Fownes, age 24, joined her father and brothers at Pinehurst for the winter season. She often brought along her golfing cohort from Oakmont, Louise Elkins, who, like Mary, would eventually become a North and South champion. A popular social butterfly, Mary enjoyed bridge and hosted card parties for her Pinehurst friends. She also demonstrated formidable dancing acumen with an Irish jig that knew no equal.

From 1909 to 1913, H.C. leased Lenox Cottage on Cherokee Road. Formerly a rooming house, the cottage was large enough to house all the family’s golfers. Bill’s wife, Sara, and the couple’s two children, Louise and Henry (Heinie) C. Fownes II (named after his grandfather), came too. W.C. and Heinie were frequent winners in father-son tournaments. H.C.’s spry mother stayed in Arbutus Cottage next door.

Thus, the Fowneses became integral members of Pinehurst’s wealthy “cottage colony.” The cottagers were a closely knit bunch who hobnobbed with one another throughout the season, even holding their own golf tournament. The Fowneses stood atop the cottage colony’s pecking order following the 1914 completion of Fownes Cottage on Village Green, arguably the most impressive home in the village.

In those days, Pinehurst was essentially a company town run by the Tufts family. Everyone in Pinehurst, including the upper crust denizens of the cottage colony, depended on the Tuftses for staples of daily living. The Tuftses owned and operated the utility services, the local lumber company, laundry, service station and department store. To defray operating costs, they instituted a quasi-governmental taxing system. To avoid outcries of taxation without representation, Pinehurst kingpin Leonard Tufts established an unofficial village council in 1923. In recognition of H.C.’s business acumen, Leonard appointed the steel baron to the new council. H.C. also led other Sandhills’ organizations, serving as president of the Pinehurst Country Club’s Board of Governors and as a member of the Pinehurst Bank’s board of directors. Donald Ross referred to H.C. as “the best citizen in Pinehurst.”

H.C.’s most significant business contribution to Pinehurst, however, occurred during the Great Depression. The unprecedented economic downturn plunged the Tufts family’s holdings into receivership. It appeared doubtful that the family would retain their sizable Pinehurst assets after a creditor bank demanded payment of a $100,000 note. A group of cottagers anted up the funds to purchase the note, thereby keeping the Tuftses afloat. H.C. contributed the largest share — $30,000. This was no small gesture given that H.C.’s own investment in Shamrock Oil was tanking at the time.

While H.C. immersed himself in Pinehurst’s affairs, W.C. was gaining wide respect in golf for reasons unrelated to his playing ability. Collaborating with several noted golf architects, Bill assisted in finalizing the layout of incomparable Pine Valley after the course’s original designer died in 1918. Gravitating toward a role as golf’s senior statesman, Bill captained American teams in matches against teams from Canada in 1919 and ’20. Then, in 1921, he organized a team of top American amateurs that challenged and beat a British aggregate in an informal competition prior to the British Amateur at Royal Liverpool.

This match served as precursor and catalyst to the first Walker Cup held in 1921 at the National Golf Links on Long Island. The USGA, having taken note of Bill Fownes’ ability to run a team and inspire its players, appointed him playing captain. The U.S. won the cup 8 to 4 with Bill splitting his two matches. He would make the Walker Cup team again in 1924.

W.C. also became active in golf administration, serving on the “Implements and Ball” committee of the USGA during a period in which the advent of steel shafted clubs was about to render hickory shafts as obsolete as buggy whips. Many feared the newfangled clubs would ruin the game. In 1923, Bill’s committee, after exhaustive testing, recommended that steel shafts be approved. This finding was met with resistance by the Royal & Ancient Golf Club, the regulator of golf outside the United States. Six years would pass before the R&A finally permitted steel.

W.C.’s committee worried that the golf ball was traveling too far — a view still common today. To address this concern, the committee recommended that the ball’s minimum diameter be increased from 1.62 inches to 1.68 inches. The USGA adopted the proposal, but the R&A again balked. While the larger “American” ball was made mandatory for the Open Championship beginning in 1974, the governing bodies didn’t officially reach agreement on ball size until 1990.

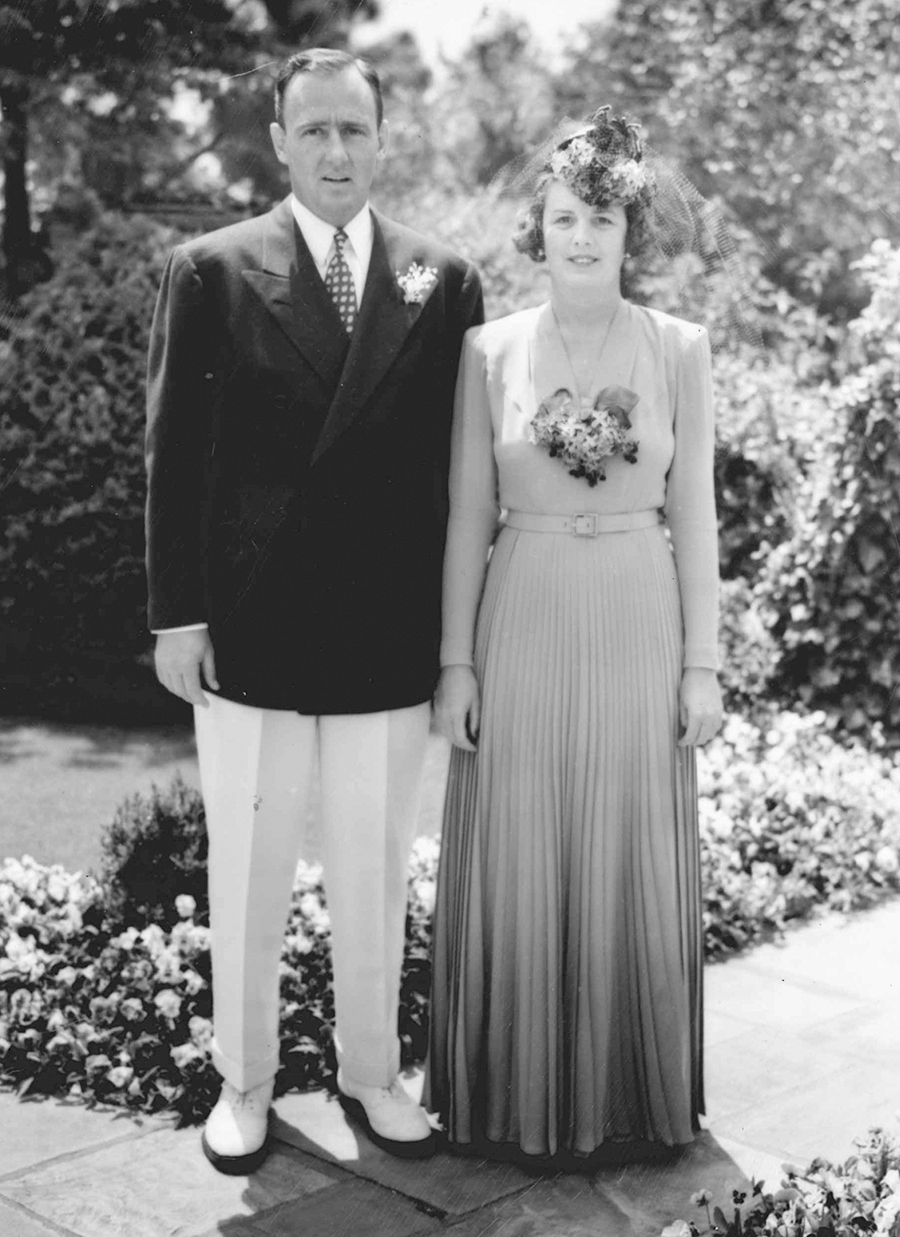

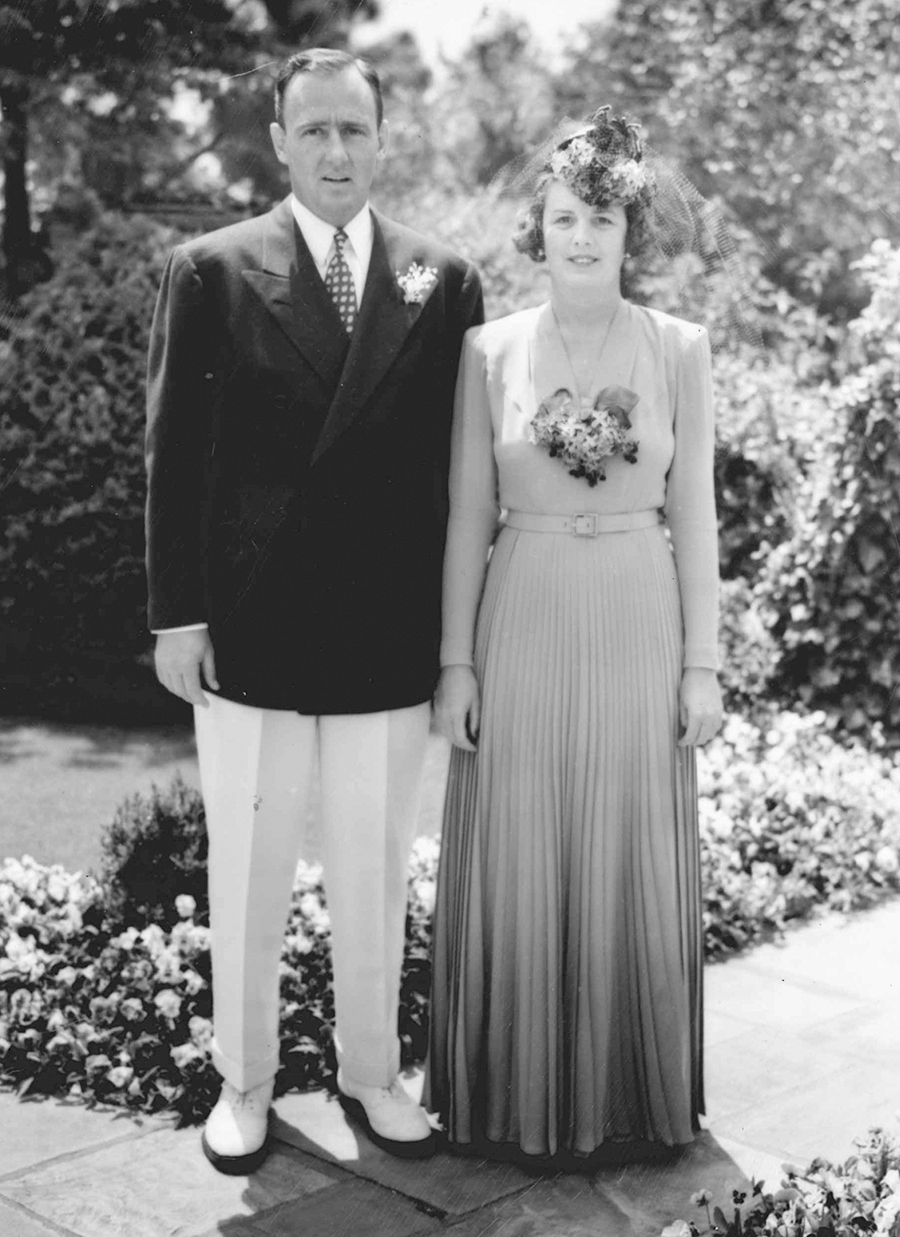

In 1926, the USGA elected Bill president of the association — the first U.S. Amateur champion so chosen. W.C. was serving in that role when he sailed with the U.S. team to Great Britain for the 1926 U.S. Walker Cup matches at St. Andrews. Wife Sara and the couple’s comely daughter Louise, then 22, accompanied him aboard the ship Aquitania.

During the ocean crossing, Louise got reacquainted with tall, handsome Washingtonian Roland MacKenzie, whom she had met at Oakmont during the ’25 U.S. Amateur. The 19-year-old Brown University phenom had surprised everyone at that championship by winning medalist honors in the qualifier. Roland’s performance at St. Andrews in the ’26 Walker Cup was likewise impressive. The young bomber split his two matches and his thunderous tee shots amazed all.

During their time together aboard ship and in Scotland, Louise and Roland shared a mutual attraction. But the prospect of romance drifted away after the ship reached the New York dock. Instead, Louise married Halbert Blue, whose family owned the Aberdeen & Rockfish Railroad in the Sandhills. The couple would have two children, Bill and Dick. Meanwhile, MacKenzie continued playing amateur golf, making the semifinals of the 1927 U.S. Amateur. Selected to the Walker Cup teams of 1928 and ’30, MacKenzie excelled, winning all four of his matches. He also married but the union did not last.

During the 1930 Walker Cup in England, MacKenzie encountered dashing Hollywood movie star Douglas Fairbanks. At the actor’s invitation, Roland moved to California and caught on as an assistant director of several films. He and Fairbanks “usually played golf every morning before going to the studio, and never wanted for company,” remembered MacKenzie. “Among those who played a lot with us were Bing Crosby and Howard Hughes.”

Tiring of Tinseltown, MacKenzie moved back to Washington in 1932. After a stint in his family’s Dupont Laundry business, he turned pro, and in 1934 became head professional at Washington’s prestigious Congressional Country Club. He entered the 1935 U.S. Open at Oakmont and found himself the early leader with a 72 in the first round, though he would ultimately finish tied for 41st. The course’s notorious furrowed bunkers caused scores to skyrocket in that championship. Pittsburgh local pro Sam Parks wound up winning with a total of 299, the second highest winning score in the Open going back 100 years from today — the highest in that period is Tommy Armour’s 301 in 1927, recorded, naturally, at Oakmont.

Louise, whose marriage to Halbert Blue had gone hopelessly awry, reconnected with Roland at the ’35 Open championship and they started seeing each other. They would marry four years later. H.C. served as the tournament chairman for the ’35 Open, his final contribution to the game as he died three months later. A whirling dervish to the end, H.C. made a 1,600-mile automobile trip to Amarillo, Texas, to check on the status of Shamrock Oil not long before his demise. W.C. Fownes succeeded his father as Oakmont’s president, successfully guiding the club through the tail end of the Depression and the chaotic years of World War II. He ultimately resigned in 1946.

In his later years, W.C. tended to his gentleman farm adjacent to a home he acquired in 1928 on Crest Road in Knollwood, growing dazzling sunflowers. He played in his card club, the “Wolves Den,” collected antiques, served on corporate boards, and traveled. On one European vacation, he and wife Sara encountered a London cab driver who shared Bill’s interest in antiques. The impressed Fowneses spontaneously invited the delighted hack to visit in the Sandhills, all expenses paid.

Charles Goren, perhaps the mid-century’s foremost bridge authority, found himself subjected to a less welcome instance of Sara’s spontaneity. In 1949, the Fowneses invited Goren to stay with them. One afternoon, Charles sat in with Sara’s duplicate bridge group and won handily. When Sara tendered Goren his winnings based on the group’s standard 1/20th cent a point, he complained, stating he never played for less than a penny a point. Sara responded by tendering payment as demanded, but also summoning a cab and telling a flummoxed Goren to pack his bags.

W.C.’s son Heinie, who had played a key role in restoring Shamrock Oil to financial health, passed away from heart trouble in 1948. Two years later, Bill himself succumbed to a heart attack at age 72. The USGA paid W.C. this tribute: “As a friend and sportsman, he bequeathed to his fellows a spirit which will always live.” Wife Sara passed away in 1951. Chick died in Pinehurst in 1954.

The passing of Bill’s generation did not terminate his family’s association with Pinehurst or amateur golf. Bill’s son-in-law Roland MacKenzie found that the pro life was not his cup of tea. He regained his amateur status after he and Louise relocated to the Baltimore area. In 1948, MacKenzie captured the Middle Atlantic Amateur Championship, a tournament he had won 23 years earlier. Roland and Louise maintained the family’s connections with the Sandhills, purchasing a second home in the Old Town section of Pinehurst.

While in Baltimore, Roland had segued into land investment and farming, and he followed the same path in Moore County. In 1955, he acquired a large parcel several miles west of Pinehurst. He transformed the land into a peach farm and vineyard. In the late 1960s, MacKenzie and other associates decided to build golf courses on the property. Foxfire Resort and Country Club’s two courses, opened in 1968, were the happy result. Roland passed away in 1988, followed by Louise’s death in 1996.

The MacKenzie’s two children, Clark and Margot, became superlative golfers. Clark MacKenzie won the 1966 Maryland Amateur Championship and later captured several international seniors’ titles. Margot MacKenzie Rawlings still resides at her parents’ Pinehurst home. She continues to play excellent golf as a member of Pinehurst Country Club’s Silver Foils. Margot’s stellar playing career includes victories in the stroke play championship of the Women’s Golf Championship of Baltimore, and championships of numerous clubs including Country Club of North Carolina.

While these playing exploits through the generations are impressive, the Fownes family’s golfing legacy will always be magnificent Oakmont. The club has hosted a record nine U.S. Opens, two Women’s U.S. Opens, three PGA Championships, and five U.S Amateur Championships. The Amateur will return to Oakmont for the sixth time this year. While the course the Fowneses built in the hills outside Pittsburgh may be their ultimate mark in golf, the family’s footprints are a veritable stampede in Pinehurst. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.