New Year (of the Cat)

Cameos for Lucky and Missy

By Deborah Salomon

Seven years just flew by since I first designated January as Cat Column Month. This was necessary because otherwise, my companions Lucky and Missy (formerly Hissy) would creep in regularly. Mustn’t let that happen; I realize some people don’t appreciate cats, or even animals.

As the French say, à chacun son goût. To each his own (taste).

My affection traces back to a lonely, only-child childhood in a New York City apartment. My parents finally relented to a puppy. I was too young to walk him alone. That lasted about six weeks. Next came Dinky, a quite manageable stream turtle who lived to 10. When we moved into a house elsewhere, I was allowed a cat named Horowitz, for pianist Vladimir, because he walked across the keyboard on the piano I hated to practice. Sadly, when I returned from a month at sleep-away camp, Horowitz was gone.

Thank goodness my grandparents had an ever-pregnant kitty and a sweet dog.

I made sure my children had pets — big, friendly dogs. Then, after they were grown with big, friendly dogs of their own, a youngish calico showed up at my door. Since then, I have been home sweet home to a parade of kitties, usually two at a time, who just showed up, usually in dire need.

I decided to retire in 2008, when the last one crossed the Rainbow Bridge.

Then, one December, a hungry black kitty with fur as sleek as a seal peered in the window. Black cats are my weakness — especially their forlorn eyes. Lucky made himself a bed under the bushes. I fed him outside until July 4th. Then, in a moment of weakness, I opened the door. He has rewarded me with 10 years of affection, intelligence and antics.

A year later, “Everybody’s,” the wide-body gal fed by many, spayed by one, got wind of my open door policy. At first she rewarded my kindness with hisses and growls. That lasted about a month. Now Hissy, renamed Missy, drips sugar.

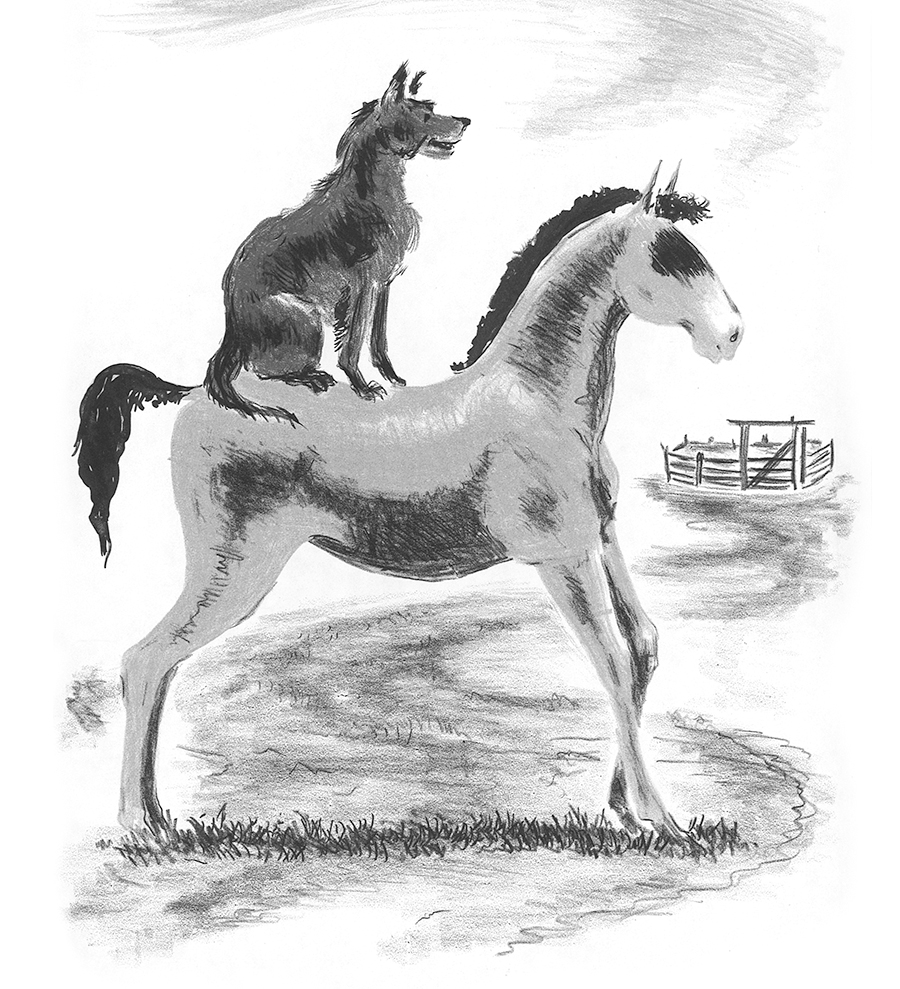

I discovered that Lucky — neutered and declawed — had been abandoned by his family when they moved. He gave Missy a long, hard stare which, I surmised, established the ground rules. They have been best buddies since, rather like an old married couple: she, a fussbudget; he the head of the household.

Wish I’d named them Archie and Edith.

Just because cats can’t speak doesn’t mean they can’t communicate. My Lucky’s eyes plead, smile, show surprise, fear, displeasure. He is a man of dignity, of routine, governed by a solar clock. He asks to go out just as the warm winter sun hits his chair on the porch. After sunset, he begins leading me to the bedroom because I keep kitty treats in the bedside table. I dole out three morsels. Upon hearing “That’s all,” he retreats to the down comforter folded at the foot, where he sleeps until 3 a.m.

During this ritual, Missy sits at a respectful distance, knowing her time will come. A feminist, she’s not.

Speaking of time, every night at 7 p.m. I watch Jeopardy! The kitties have chosen this moment for their daily aerobic workout, triggered by the Jeopardy! theme music, which triggers some angry-sounding music of their own. They pounce, roll around. Then, like a summer thunderstorm, it’s over. He lowers his head and she licks it clean before they trot off together.

Cats, especially elderly ones, sleep upward of 20 hours a day. Mine have nests, some self-styled, others mom-made like a fuzzy blanket in a box.

Lucky prefers a dark corner of my closet. Missy sleeps around. The first chilly days I position two heating pads on the bed. I started with one, since Lucky has an arthritic hip. Missy claimed half. Now, mesmerized by heat, they nap there for hours. I barely cop a corner for my arthritic shoulder.

Another behavioral oddity concerns the water bowl. I feed them in the kitchen — two feeding dishes, one water bowl. In the winter, they spend so much time on the heating pads that I put a water bowl beside the bed, a wide soup bowl decorated with flowers. Lucky will walk from the kitchen into the bedroom for a drink. Same water, changed twice a day.

Cats . . . aloof? I can’t sit down to watch Wolf Blitzer without a lapful. A pause in rubbing and scratching nets a paw. OK with Lucky, but Missy has claws.

Food is usually an issue with cats. I mix best-quality kibble with best-quality canned, or something I’ve cooked for them, like chicken, liver or fish. I once had a kitty who accepted only cod and pork liver — wouldn’t touch tilapia or chicken liver. People tuna costs half as much as Fancy Feast, so sometimes they get a spoonful. Of course they have favorites off my plate. Missy goes berserk if I’m eating slivers of smoked salmon on a bagel. Lucky loves to lick the cover of a Greek vanilla yogurt container. The best is watching him lick the salt off a potato chip, leaving it limp. Spaghetti with plain tomato sauce is another winner . . . just a strand, because I wouldn’t want to spoil them.

No, cats can’t talk. They fascinate with wordless actions, instincts, habits. Connecting with an animal is a proven therapeutic. I can feel the tension flee my shoulders as I stroke Lucky’s satiny fur. Missy makes me laugh on the grimmest day. Best of all, a trust once established endures.

Too bad the same cannot be guaranteed with humans. PS

Deborah Salomon is a contributing writer for PineStraw and The Pilot. She may be reached at debsalomon@nc.rr.com.