New Yorker Aymar Embury designed the Sandhills’ most iconic buildings

By Bill Case

By 1911, 31-year-old Aymar Embury II was already regarded in metropolitan New York circles as a superb architect of “country homes.” A steady stream of commissions had come his way from upper-middle-class clients impressed with the Princeton grad’s uncanny ability to design floor plans containing generously proportioned rooms despite modest square footages to work with.

While employed as a draftsman for an architectural firm in the city, Embury entered a 1905 Garden City, Long Island, architectural design competition. He submitted two plans and won both the first and second place prizes. His layouts received favorable mention in publications like Ladies’ Home Journal, and he succeeded in parlaying the public attention into commissions for 10 new home designs. This uptick in fortune enabled Embury to open his own architectural shop in 1907, and he doubled down on his newfound notoriety by writing a book in 1909, One Hundred Country Houses: American Examples. It was the first of numerous architectural tomes he would author.

Notwithstanding this success, Embury resented being pigeonholed as a specialist in country house architecture. As the first decade of the 1900s came to an end, he yearned for more challenging assignments involving bigger buildings. His initial opportunity to build a major public edifice came from an unexpected location — 560 miles south in North Carolina’s Sandhills.

The resort town of Southern Pines needed a new hotel after its largest, the Piney Woods Inn, burned to the ground in 1910. John Boyd, whose family owned vast Sandhills acreage, formed a corporation for the purpose of constructing a grand new hotel that would overlook the downtown from a vantage point high on a ridge at the eastern end of Massachusetts Avenue. Several locals joined Boyd as shareholders in the venture.

How Aymar Embury, a New York-based country house designer, persuaded John Boyd and the other investors to retain him as the architect for the Highland Pines Inn in 1911 is uncertain, but the Ivy League may have been involved. Like Embury, John Boyd and his two sons, Jackson and James (the celebrated novelist), were all Princeton alumni. So was the project’s landscape architect, Alfred Yeomans.

Regardless of how he obtained the commission, Embury’s efforts resulted in an eye-popping Colonial Revival structure. The magnificent white exterior of the 200-foot-long structure featured linear columns fronting spacious porches, three front entrances, 100 bedrooms, and 60 baths. The hotel’s modern amenities included its own electric and steam plants, and a laundry. The Highland Pines became the town’s social center and a favorite haunt of the foxhunting set.

Embury also designed several guest cottages for the inn and three private homes, all within easy walking distance of the grand hotel. Then, John Boyd’s sister Helen Dull (founder of the Southern Pines Civic Club) hired Embury to draw up plans for her prospective residence on Valley Road. Dull would unostentatiously call the place “Loblolly Cottage,” but the 1918 finished product, with its hipped triangular roof, numerous gables, diamond-shaped brick facing and seemingly unending width, appeared more like a majestic manor house befitting a duchess.

Though Embury’s Sandhills projects were expanding his architectural portfolio, that undivided attention to his work had exacted a personal cost. “I had not had a day off, even Saturdays or Sundays, since I had left college, not even for sickness,” he wrote. “Perhaps that is one of the reasons my wife (Dorothy, whom he had married in 1905) and I could not get along.” Parents of three sons (Edward, Carl, and Peter), the couple separated in 1913 and ultimately divorced.

Just as the 38-year-old began receiving recognition for talents stretching far beyond the design of country lodgings, America entered World War I. Embury became a commissioned officer in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers stationed in France as part of Gen. John J. Pershing’s American Expeditionary Force. When the Signal Corps failed to implement a plan to use artists to depict the life and activities of the AEF to boost morale in the field and support for the war back home, Capt. Embury asked if he could. He was given the go-ahead and the unit that was formed ultimately included eight artists, traveling freely, often to the front.

An excellent artist himself, the captain was responsible for designing both the Army’s Distinguished Service Cross and the Distinguished Service Medal. Embury only mentioned one of the awards in his resume, saying of the other that he did not “like the form in which the citation is written, and while it is complimentary enough, it makes me a little tired.”

After 14 months of military service and a ticker tape parade for Pershing’s returning doughboys, Embury reopened his New York City office and was promptly deluged with new business. The building boom of the Roaring Twenties created high demand for name architects like Embury, and the Boyds (James and Jackson, since their father passed away in 1914) were among the clients first in line.

James Boyd had decided the Sandhills would be the ideal place to pursue his dream of writing novels, and in 1920 he retained Embury to plan a home resembling that of Colonial planter William Byrd of Westover, Virginia. The result was Weymouth House, a rambling, mostly brick structure situated on high ground above Connecticut Avenue. In 1921 Boyd moved in, and four years later would write the Revolutionary War saga Drums. A surprise bestseller, the novel catapulted Boyd to the upper ranks of American writers. The house now serves as home for the Weymouth Center for the Arts and Humanities.

Boyd was not the only Southern Pines resident to hire Embury. Homes in the new Weymouth Heights development were sprouting up faster than spring dandelions, and Embury designed many of them. Admirers of his work found it easy to identify an Embury-designed home but were often hard-pressed to classify the house’s style of architecture. Elements of English cottage, Federal, Georgian, Norman, Colonial Revival and Dutch Colonial were frequently blended within the same house. Stuck for a label, locals began referring to his architectural creations as “Sandhills style.”

Though he employed modern variations to classical design concepts, Embury was critical of the genre of “modern architecture” itself. “Modernists believe that the essence of their work is to do something that has never been done,” he ruminated. “I suppose some of the architects do not use buttons or neckties when they dress!”

When asked his views regarding the work of acclaimed modernist Frank Lloyd Wright, he would pithily respond, “No closets!”

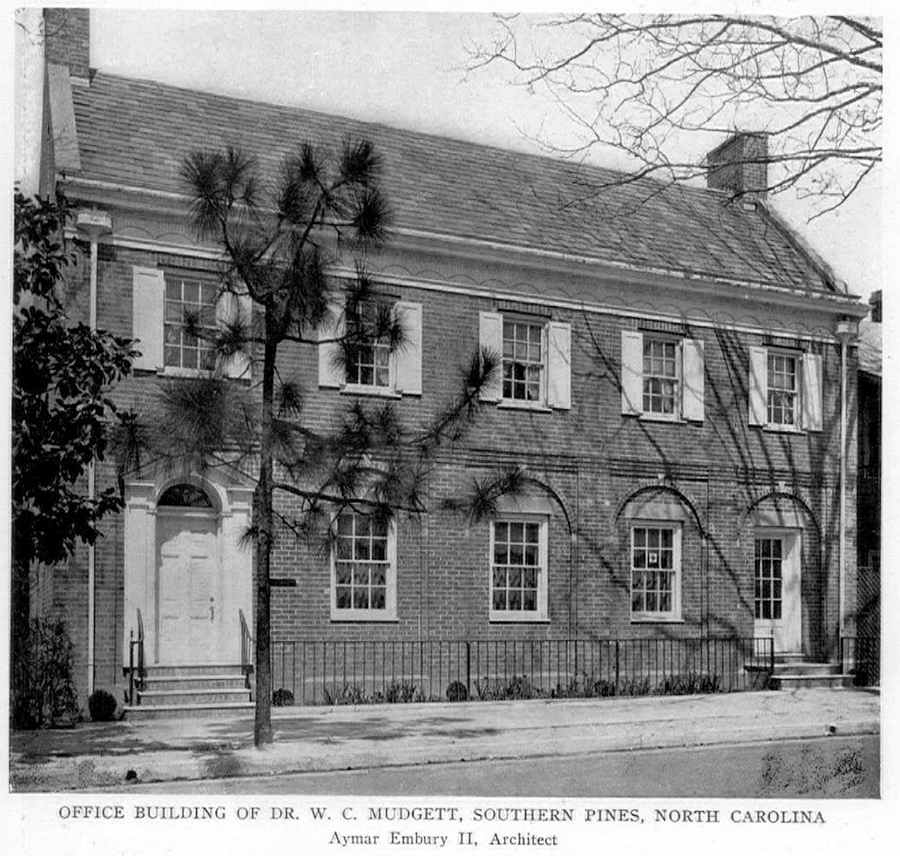

Opportunities for designing commercial structures also abounded in the Sandhills. After an April 1921 fire destroyed many of the wooden buildings on West Broad Street in Southern Pines, Embury prepared plans for several of the replacement structures, including the U-shaped, old-English style Citizens Bank building, and Dr. Mudgett’s office at 140 S.W. Broad St.

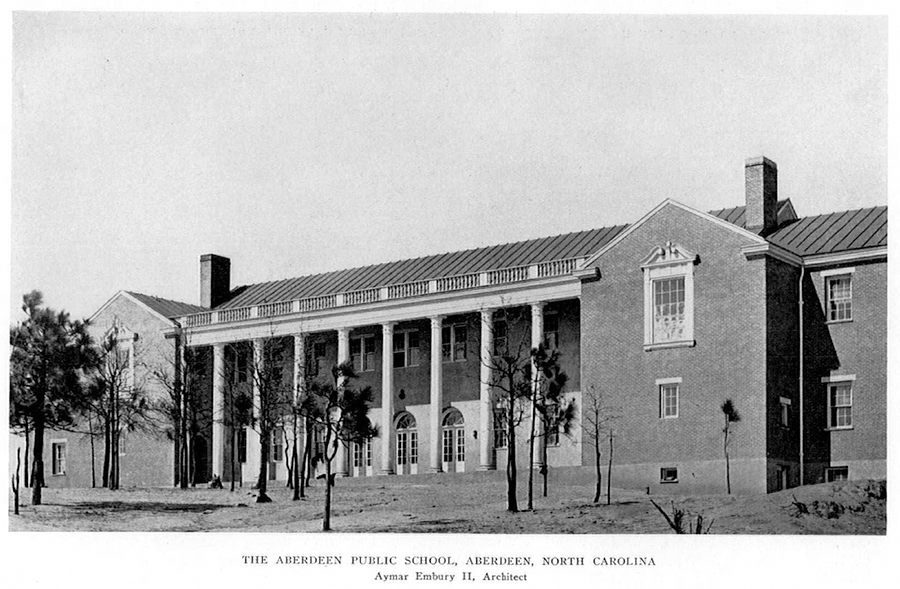

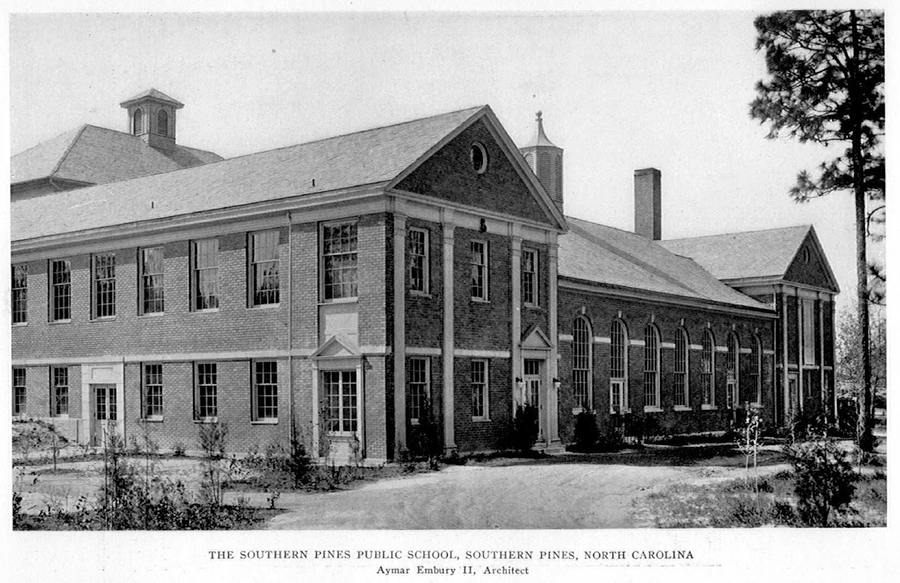

Both Southern Pines and Aberdeen needed new schools. The peripatetic architect drafted blueprints for both. According to Embury, the Southern Pines Town Council passed an ordinance requiring that he be hired as architect for all new commercial buildings on Broad Street. The measure was rescinded at the architect’s request.

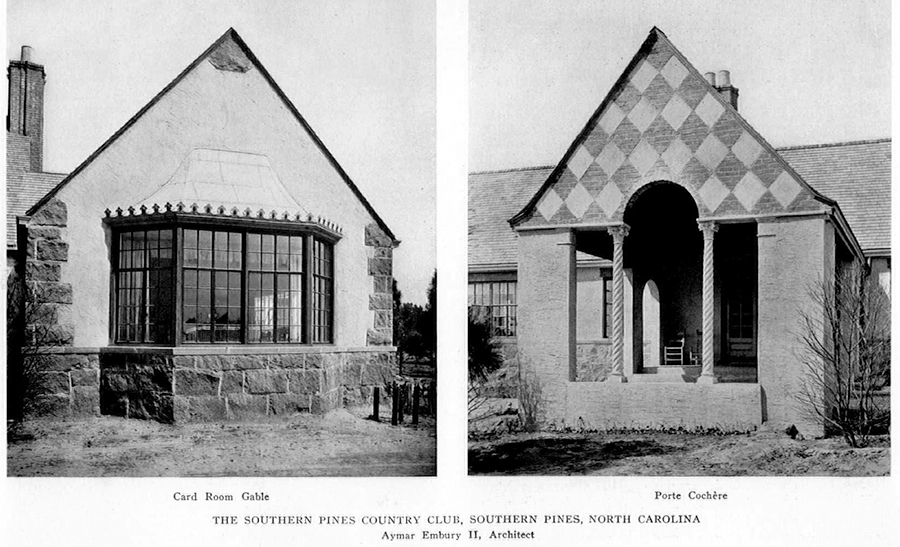

One of Embury’s favorite Sandhills projects was the planning of the Southern Pines Country Club’s clubhouse. Architectural writer Russell Whitehead praised it as “the loveliest small clubhouse in America,” with its “sandy buff stuccoed walls, accents of sandstone, and red brick.” Regrettably, the building would succumb to fire in the 1960s, mirroring the fate of the Highland Pines Inn that burned in 1957.

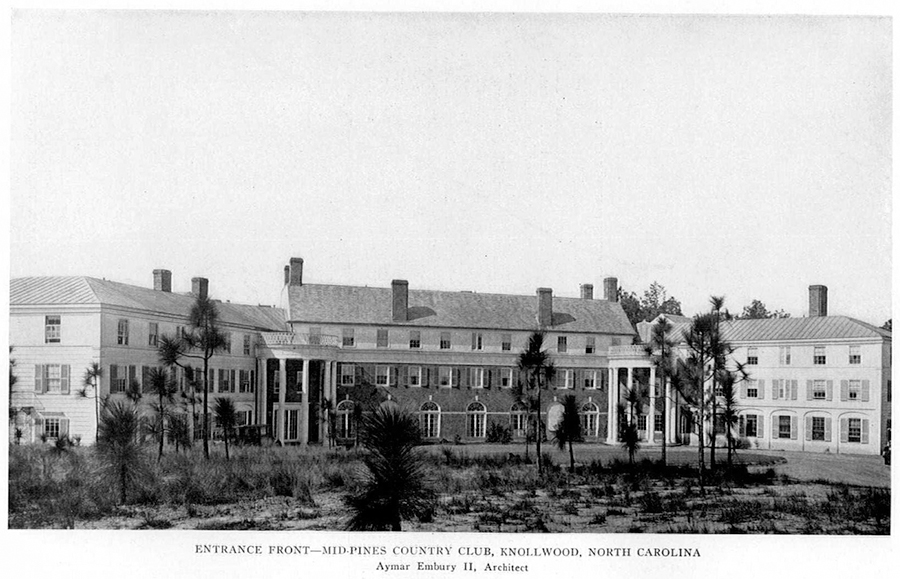

In Pinehurst, Leonard Tufts contemplated the expansion of his mini-empire by building a second golf resort on Midland Road. He formed a stock company that engaged Embury to design a combination hotel and clubhouse to serve the Mid Pines Country Club and its Donald Ross-designed course. Embury submitted plans for a three-story edifice containing 100 bedrooms, all with private baths. The proposal called for a 500-foot-wide, crescent-shaped Georgian structure. The February 2, 1921 edition of The Pilot reported that “the first half is being started at once. When membership warrants it, the second half, in harmony with the first half, will be added to make a perfect whole.”

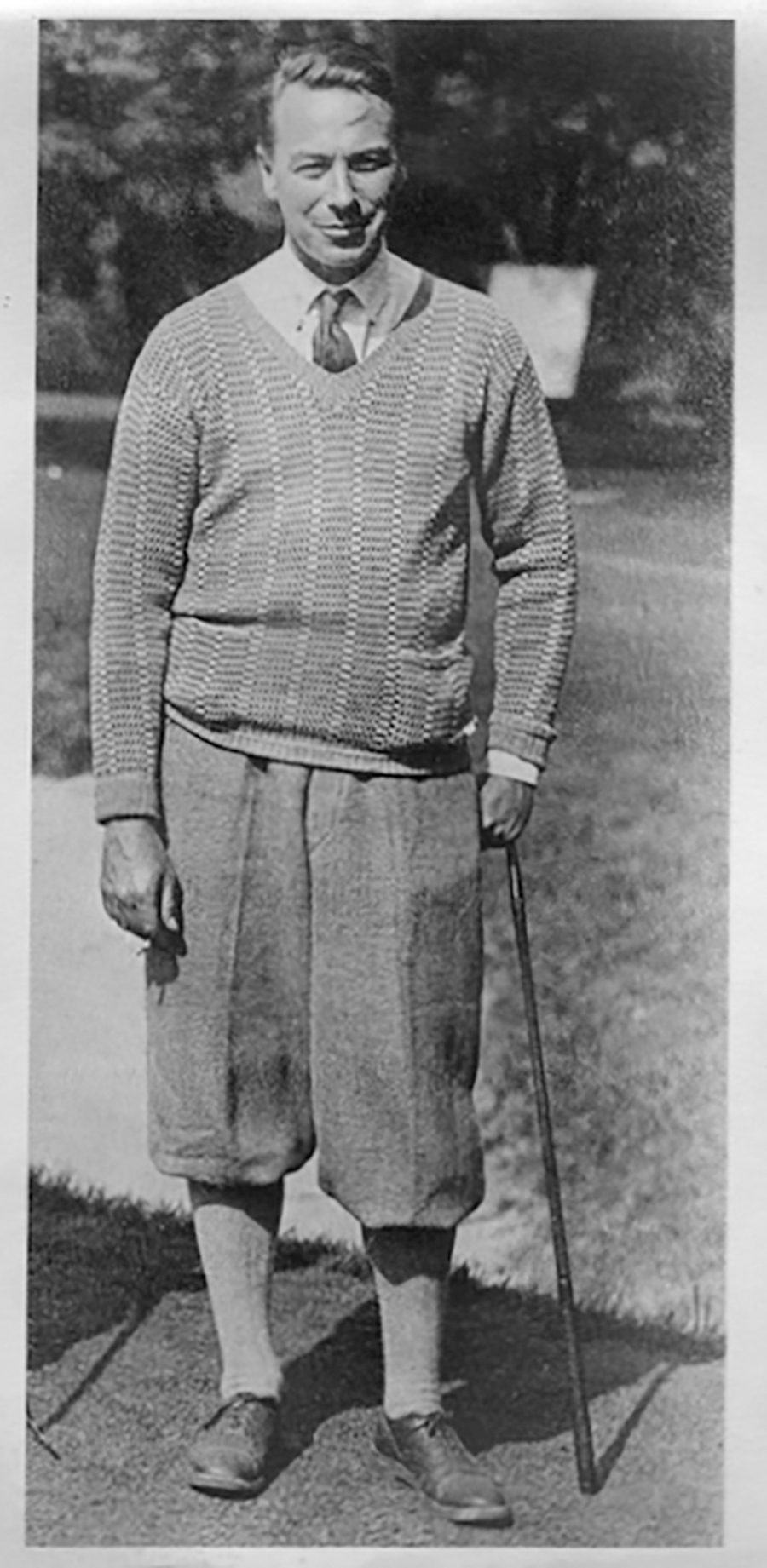

When the hotel and course were finished, it was evident that the Ross-Embury pairing had created something special. For nearly 100 years, the venerable inn has provided a spectacular backdrop for golfers playing their uphill approach shots to the 18th green. A golfer himself, in April of 1921 Embury captured first prize in the third flight of Pinehurst’s Mid-April tournament.

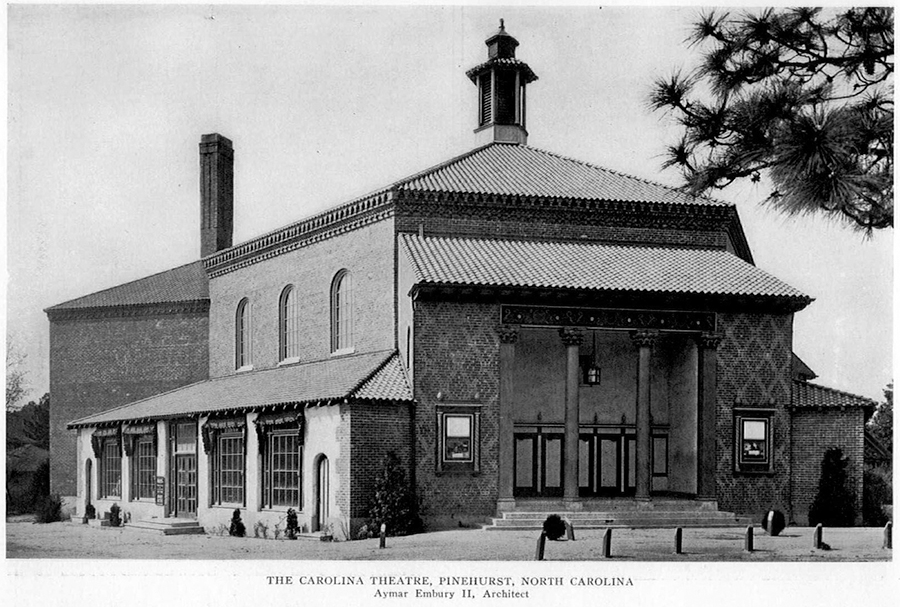

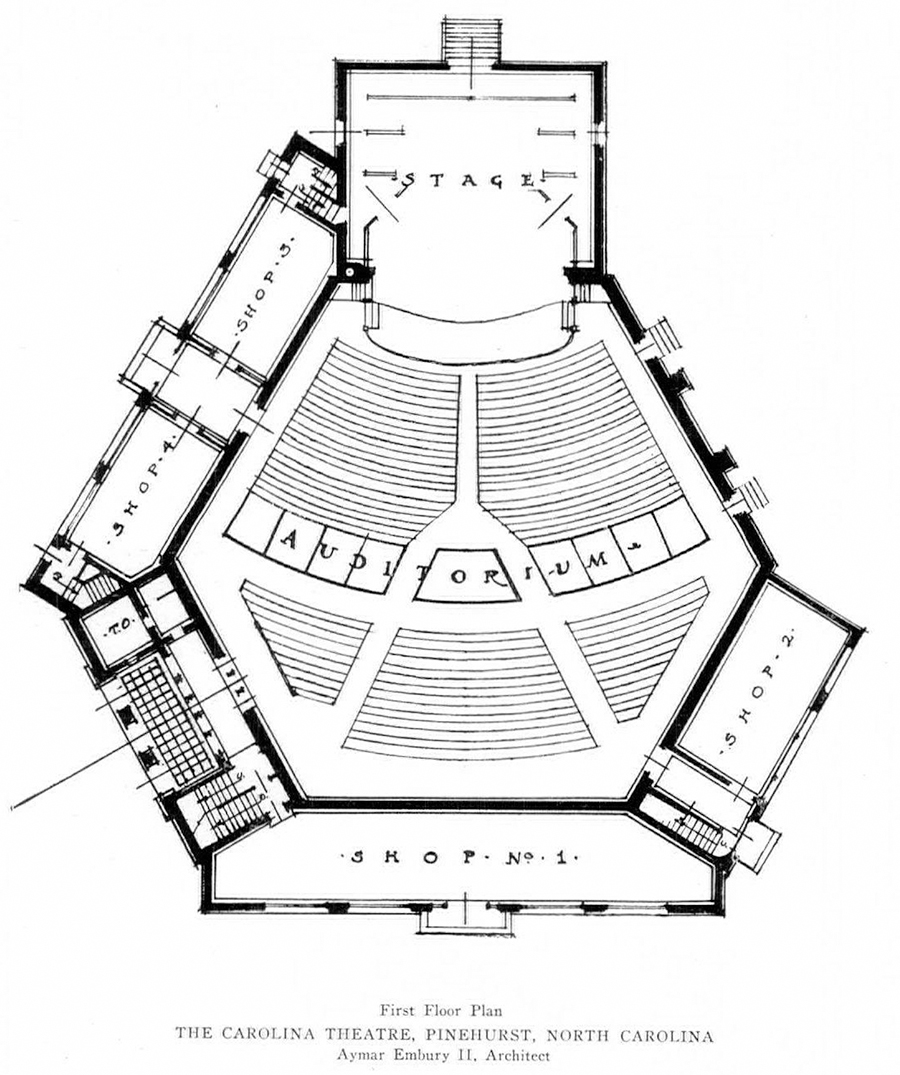

After the Mid Pines job, Tufts kept Embury busy on numerous Pinehurst projects. One of the most challenging involved shoehorning the new Pinehurst Theatre building into an awkwardly shaped lot. He solved the difficult quandary by devising a hexagonally shaped, vaguely Byzantine structure seating 500 people. The theater opened in 1923 to rave reviews and achieved recognition as one of the premier Southern movie houses. Tufts also asked Embury to plan a new business block in downtown Pinehurst, and several Embury-designed metal-roofed commercial buildings — including an annex to the Harvard Building — grace Market Street today.

The omnipresence of Embry structures caused the Moore County News to remark that he had “set his sign manual so persistently on Weymouth Heights, as well as on Knollwood and Pinehurst that the Sandhills country is becoming an Embury dream.”

Still, the ambitious architect did not land every commission. After getting wind in 1924 that Tufts was contemplating building a third Sandhills golf resort (ultimately the Pine Needles Inn), Embury made a direct pitch to Tufts for the business, unabashedly writing, “Don’t you think you would like to have me as your architect for this job?” But this was one project that eluded his grasp. Instead, Tufts chose family member Lyman Sise of Boston as the architect for Pine Needles’ massive English Tudor hotel and clubhouse (now Pine Knoll at St. Joseph of the Pines).

This slight bump in the road did nothing to hinder the spreading of Embury’s reputation for architectural excellence to other Southern locations. He obtained multiple commissions for homes in Atlanta’s upscale Buckhead neighborhood, and designed clubhouses for Hope Valley Country Club in Durham, Charlotte Country Club, and Mountain Brook Club in Birmingham, Alabama. According to the Princeton Alumni Weekly, Embury undertook additional responsibilities on the Mountain Brook job, selecting the club’s “silver, linen, men’s uniforms, etc.”

By the mid-1920s, Embury was also engaged in major commercial projects in the North. Architectural work for churches, libraries, banks, apartment buildings, hotels and country clubs flooded his East 61st St. office in Manhattan. His son Edward joined the firm and became a respected architect in his own right. The son learned close up how his father used formidable artistic skills to impress prospective clients. In the course of an hour-long meeting, the senior Embury would freehand an attractive and detailed sketch of the structure contemplated by the owner. The depiction usually wowed the prospect, and Embury would be retained.

Doors to another segment of architecture opened for Embury during the ’20s. He segued into a go-to designer for college buildings at the University of Virginia, Wesleyan College, Hofstra College, Williams College, and Kalamazoo College. Eventually, Embury’s alma mater, Princeton, would seek him out for design work on numerous projects, including West Hall, a war memorial at Nassau Hall, and the gargoyle-guarded Dillon Gymnasium — still the university’s all-purpose athletic center.

It is mildly ironic that Princeton would hire Embury, given the dismal academic record he posted during his time at the university. At the urging of his father, an attorney and Columbia University graduate, he entered the Ivy League school in 1897 at the age of 16. A year later, Embury sneaked away from Princeton and enlisted in the military, hoping to fight in the Spanish-American War. The Army promptly sent him back to school after his age was discovered.

Embury described his four undergraduate years as “good the first year, fair the second, poor the third, and awful the fourth.” The civil engineering student’s marks for the final semester of his senior year matched the report card of John “Bluto” Blutarsky of Animal House, 0.0. “I suppose” Embury confided, “that I am the only person who graduated from a decent American college who failed in all subjects second term senior year.” He passed those subjects upon re-examination and received his degree in 1900.

Despite this unimpressive performance, Princeton accepted him into a fellowship program entailing a year of study in architecture. He would credit fellowship professor Allan Marquand for inspiring a newfound passion for learning. “He fired (me) with an enthusiasm,” Embury wrote in 1938, “for the beauty, not only of antiquity, but of common everyday things that has been a guide and a way to me these forty years.” His turnaround during the fellowship led Princeton to hire him as an instructor in architecture. Embury moonlighted in that position during his early years laboring in the trenches of New York architectural firms.

After Embury’s parade of successes during the 1920s, he possessed sufficient resources to indulge in the good life. He moved to a house on E. 62nd St. that enabled him to stroll from home to office in minutes. He wed again, marrying noted landscape architect Ruth Dean, and the two collaborated on projects. A daughter, Judy, was born to the couple. Embury acquired a spacious getaway home in East Hampton on Long Island and played golf regularly at the posh Maidstone Club.

Another of Embury’s pastimes was researching his family’s genealogy. His ancestors were French Huguenots who, for religious reasons, fled their native country in 1665, settling first in England and then Ireland. In 1758, several Embury family members immigrated to New York, and his great-great grandfather’s brother, Philip Embury, was an early founder of the Methodist Church in America.

Though an old-line, socially prominent family, Embury’s connections were not enough to keep his lucrative income stream flowing once the Great Depression hit in the 1930s. Commissions for projects in the Sandhills terminated altogether, and new builds in metropolitan New York slowed to a trickle. The sudden death at home of wife Ruth compounded Embury’s mounting distress. In 1930, he was appointed to a government gig as the New York Port Authority’s consulting architect. Still, the workload was light until New York City’s new Parks Commissioner Robert Moses asked him to serve as lead architect for the new Central Park Zoo in 1934. The financing for the project was coming from the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a federal agency vital to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal plan to revitalize the national economy through federally funded public projects that put men who would have otherwise been unemployed to work.

Moses commandeered the Central Park Arsenal and converted it into the Parks Department’s new home. Conveniently, the Arsenal was located adjacent to the site selected for the new zoo. To assist Embury, a platoon of out-of-work, but nonetheless capable, New York architects was hastily hired. Most did their work on drafting tables set up in a garage at the Arsenal. The architects were paid $80 a week, a manna-from-heaven windfall at the time.

Sixteen days after starting the assignment, Embury handed Moses blueprints for the zoo’s nine new buildings. Producing quality work at a frenetic pace did much to cement the working relationship between the two men. Embury received some favorable, albeit humorous, press from the zoo project. During the planning of the monkey house, former New York Gov. (and Democratic presidential candidate) Al Smith sent the architect a note requesting that his pet monkey Joe get good quarters. It seems that Joe had once been the governor’s house pet before being transferred to the old zoo (called the “Menagerie”), where Smith visited the ape regularly. According to an article in The New Yorker magazine, Embury played along, stopping by the Menagerie to show Joe the monkey house blueprint. The chimp promptly slapped it away. When the ex-governor was informed, he advised Embury not to worry because Joe “used to live in a mansion in Albany and he is too particular.”

For both Moses and Embury, the Great Depression’s hard times began creating opportunity. They would become involved in building hundreds of projects in the city financed just as the zoo had been. The politically astute Moses figured out how to be first in line to receive the millions of dollars doled out by the WPA and other federal agencies. To manage the funds, he arranged to have various public authorities created, and placed himself in sole charge. All types of public works eventually fell within Moses’ purview, and he exercised nearly dictatorial control over them.

Though never elected to public office, the megalomaniacal “master builder” held more power in New York than any politician. From his post at the Arsenal, Moses supervised an army of 1,800 professionals and workers who scurried to satisfy the micromanaging commissioner’s every whim.

Though Embury characterized working at the Arsenal during the New Deal period as “a madhouse,” he relished the challenge. As Moses’ favorite architect, he put his personal stamp on over 600 WPA public works projects in the city, including schools, hospitals, marinas, police and fire stations, museums and athletic facilities. Many were parks; 11 were city swimming pools. During the summer of 1936, temperatures in New York reached 106 degrees, and Embury’s pools provided welcome relief to the sweltering masses.

The facilities were designed to evoke images of faraway places. Called “palaces for the poor,” Embury structures that resemble Romanesque fortresses and Norman castles still grace city pools today. He also planned the New York City Building (now the Queens Museum) for the New York World’s Fair of 1939. Embury handed Moses a set of complete blueprints with elevations for the latter project just four days after being requested to prepare them. According to Embury, “They were adopted on the spot.”

But in New York, Embury is best remembered for his design work on bridges. Prior to the 1930s, ferries were often necessary to travel to and from the various islands comprising the city. Working frequently with the noted engineer Othmar Ammann, significant Embury projects included the massive Triborough Bridge (now the Robert F. Kennedy Bridge), the Lincoln Tunnel, Marine Parkway Bridge, Bronx-Whitestone Bridge, the Henry Hudson Memorial Bridge, and Jamaica Bay Bridge. His civil engineering training at Princeton, while rudimentary, helped him establish rapport and a “spirit of collaboration” with Ammann, the engineer — something of a rarity at the time.

If Embury’s work activities were occasionally chaotic during the ‘30s, there was also upheaval in his personal life. Two years following Ruth Dean’s 1932 death, he married Josephine Bound, but the union did not last and soon he was single again. In his mid-50s, he still cut a dashing figure. The New Yorker described Embury as “young-looking, brown-haired, sort of Jimmy Walkerish [a stylish New York mayor of the era] man.” According to grandson Philip Embury, Aymar was a “Renaissance man” who carried himself with a confident, patrician air — sort of a male version of movie star Katharine Hepburn. In 1940, he married fourth wife Jane Shebbehar, a woman half his age who worked in the office.

Though his accomplishments in the Sandhills were years behind him, Embury kept tabs on developments in the area. The Pilot reported that Embury was advised by a friend in 1936 that the federal government was funding a new post office on Broad Street in Southern Pines. Embury replied that he would submit “a sketch to the Supervising Architect of a building which would conform to the state of architecture here.” The government waived its usual requirement of using its standard exterior post office design and adopted Embury’s plan featuring a diamond-paned window over the entrance. Soon after, he designed an adjoining building for a new library (now housing the Southern Pines utilities operations). An Embury-designed wing was added to the library in 1948 and dedicated to the memory of his early benefactor James Boyd, who had passed away four years before. Embury donated the plans for the wing “in token of his friendship” with the novelist.

With the advent of World War II, the furious pace of public works construction was channeled instead into defeating the Axis powers. After the war and easing into his 70s, Embury stayed as busy as he wanted to be but gradually delegated business affairs to son Edward. He and his wife enjoyed traveling abroad. Jane would later tell the grandchildren that tears would come to her husband’s eyes when encountering ancient, classically designed structures that once had inspired his own designs.

In 1955, Embury decided to sell his E. 62nd St. residence. The eventual buyer was film star Tallulah Bankhead, a woman known for her promiscuity as much as her acting. Embury family lore, related by Aymar’s grandson Edward Embury Jr., says that Embury, then 75, gave Ms. Bankhead a personal tour of the home. While inspecting the bathroom, the architect and star lingered inside the generously sized shower to discuss the advisability of converting the area to a bathtub. Thereafter, Embury would puckishly regale friends about the time he shared a shower with the adventurous “Tallu.”

Embury’s grandchildren, Philip Embury, Edward Embury and Dottie Statts, and Jane’s nephew Michael Brennan remember happy times visiting Aymar and Jane in East Hampton in the late 1950s and early ‘60s. Aymar organized games and swimming contests and would fork over quarters to the winners.

Embury passed away in 1966 at age 86 after a protracted illness. Jane would remarry Robert Benepe. After her death in 1995, family members attending her funeral in New York were treated to a guided tour of Aymar Embury-designed buildings, bridges, pools and parks. The gentleman conducting the tour was Adrian Benepe, the son of Jane’s second husband. Coincidentally, Benepe was then employed by New York City as its Parks Commissioner, Robert Moses’ old post.

The New York Times covered the family gathering, making a belated but fitting tribute to Embury, writing, “As chief architect for Robert Moses, he did as much as anyone to bind the city together and to help it dig its way out of the Depression.” Fashioned during its formative years, Embury’s footprint in the Sandhills — a land without soaring bridges or commuter tunnels — may have been just as great. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.