Summer Boy

The summer we were seventeen

I watched you in the sun.

Blond and blue

Beside the pool

Teasing girls you hardly knew.

Jackknife off the high dive —

Daring other golden guys.

I watched. You didn’t see.

Dark and dusky me.

— Phillis Thompson

It’s a business, an art and a science and it all eventually winds up on our tables. These are just a few of the folks who make dining in the Sandhills a fresh, friendly, delicious experience.

Dale Thompson

Dale ThompsonHilltop Angus Farm

“I’ve been here all my life,” says Dale Thompson, looking out over the rolling hills near the Uwharrie National Forest from the second story of the green barn where he organizes the distribution of his grassfed beef. His parents were loggers, then dairy farmers. “Things change. We have a cattlemen’s meeting every month during the winter. We had a guy from N.C. State come and put on a program about direct marketing. My oldest son talked me into trying it.” They started with Earth Fare in Asheville in 2011. “I figured that if it was good enough for Earth Fare we could try a market. It’s a big step to go to a market. You’re afraid your product will be rejected. We started in Southern Pines and Pinehurst. It just grew and grew and grew. Now we sell all of our production. People like to have a clean food, know what’s in it, know where it comes from.” Hilltop adheres to the protocols of the American Grassfed Association. The cattle are never given growth hormones or antibiotics. The beef is processed and packaged by Mays Meats in Taylorsville. In addition to Hilltop’s beef, artisan salami and sausages, they offer lamb on a limited basis and heritage pork. They sell directly to Ashten’s, who has been with them since the beginning, and Sly Fox. Their reach extends as far as Wilmington. Thompson has roughly 300 customers there who place orders online. “We meet them in a parking lot on Sunday morning, the first Sunday of each month,” he says. “Anywhere from 50-70 people come in an hour and a half.” Thompson’s wife, Sharon, grew up on a farm 3 miles south of Mt. Gilead. “She was raised on a farm. I was raised on a farm,” Dale says. “I’m born on the land. The only way I can leave it is to sell it.” And that’s not about to happen.

Ben, Jane and Gary Priest

Ben, Jane and Gary PriestGary Priest Farm

The transition started with asparagus. Where there once was a hillside full of tobacco, now the farm on Bibey Road in Carthage grows nothing but produce. “I started playing with asparagus,” says Gary Priest. “Somebody said I couldn’t grow it.” Besides, the farmhands needed something to keep them busy in the spring. “Now all the tobacco’s gone to a different farm,” says Gary’s son, Ben. “We should be growing more produce this year than we ever have. That field right there gets triple-cropped. Soon as those peas are done, I planted kale where the first pea patch was. Soon as the potatoes are gone, something else will be there. Collards or something. We have carrots, onions, garlic. Green beans on the hill where you drive up.” The Priest farm devotes somewhere between 1/4 and 1/2 acre to asparagus. “Then we had more than we could just sell to the restaurants and we started going to the farmers market and the Farm to Table got started,” says Ben. “We don’t plant on speculation. Half of it is sold when we plant it.” And they’re particular about what they deliver. Someone once approached Gary looking for advice on marketing a crop of strawberries. “You send them the very best you got because you’re not just selling strawberries,” he told them. “You’re selling your farm, your name, your reputation and they won’t forget it you dump something on them.” The Priests supply produce to nearly a dozen local restaurants, including Ashten’s, Chef Warren’s, Elliott’s on Linden, Restaurant 195, Sly Fox, Ironwood, Scott’s Table, Thyme and Place Café and The Bell Tree Tavern. “Stuff that’s grown under plastic is fine,” says Gary, “but it doesn’t taste like something grown in the bare ground.”

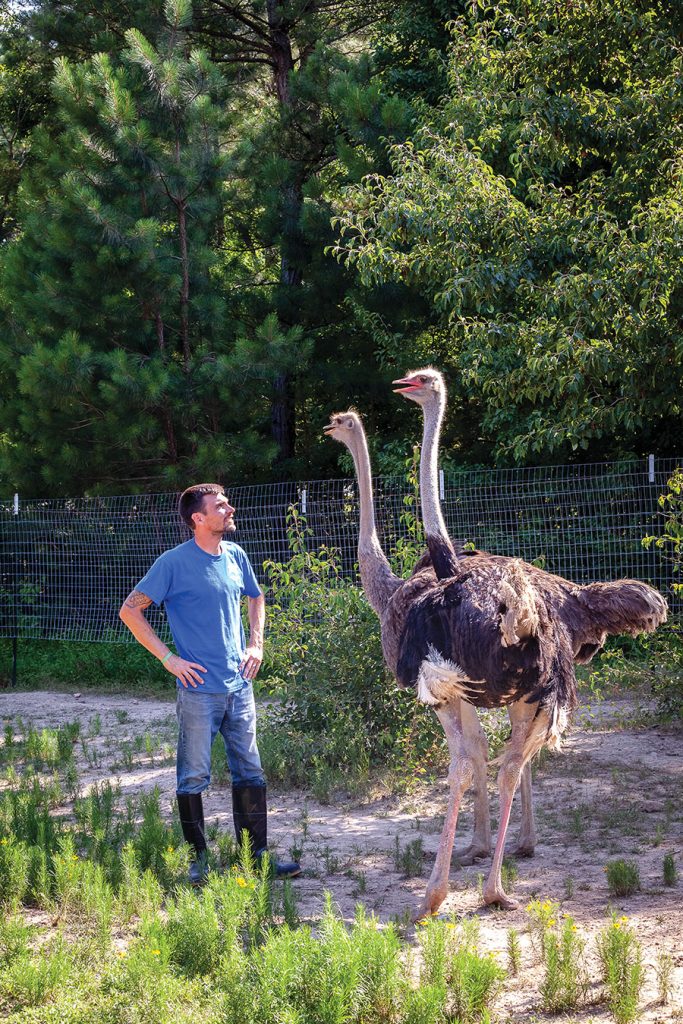

Ryan Olufs

Ryan Olufs Misty Morning Ranch

In September 2015, Ryan Olufs and his wife, Gabriela, crammed everything they didn’t sell or give away into their Dodge Challenger and moved from the San Fernando Valley in California, to Robbins, North Carolina, stopping along the way to see Yellowstone and Mount Rushmore. “We wanted to move to a more rural region, get away from the big city lifestyle,” says Ryan. They did it in a big way. After purchasing a farm in Robbins, they decided they needed to put something on it. “I came across ostrich, really for the feathers. Then we found out that the meat is the No. 1 product,” says Ryan. “Wow, you can eat an ostrich? The more we researched it more it appealed to us. Being first-time farmers, they don’t require as much husbandry as other animals. Ostriches have one of the strongest immune systems of any animal. They’re completely immune to avian flu. They require no vaccines. They lay eggs. And it’s just about the healthiest meat you can eat, either red or white.” So, with the help of Ryan’s brother, Robert, who is in the military, the Olufs planted their urban roots. They revitalized the pastures and put in fencing. They started with two birds, Ed and Bella, in 2016. Now they have 19 birds, 15 breeding stock and four juveniles for processing, done by Chaudhry’s in Siler City. “There’s exploding demand outside the United States,” says Ryan. “Right now ostrich sells for more than Kobe beef in Japan.” With production in its infancy, the Olufs sell locally at farmers markets in Southern Pines and Pinehurst and a butcher’s market in Raleigh. “Chef Warren’s has it on the menu,” says Ryan. “Sly Fox has done it before. Ashten’s buys the eggs from us and they make crème brûlée and ice cream out of them. People will actually come to the farmers market to tell us how good the ice cream is at Ashten’s.”

Martin Brunner

Martin BrunnerThe Bakehouse

Martin Brunner’s father, Kurt, who started The Bakehouse, was a master baker. Martin’s grandfather was a master baker. His great-grandfather was one, too. And his great-great-grandfather before that. Five generations of experience floats out of the The Bakehouse kitchen on the scent of fresh bread. Martin, who emigrated from Austria in 1991, is also the baking and pastry coordinator at Sandhills Community College. The Bakehouse menu’s Spanish flair comes from Martin’s wife, Mireia, and her mother, Dolores. “A lot of the recipes here are my mom’s, my dad’s, my grandfather’s, my great-grandfather’s,” says Brunner. “Actually the recipe we use the most is my grandmother’s Black Forest cake. We’ve been in the United States 26 years and I was a little kid eating it, so for 34 years we’ve made the same cake.” In addition to the restaurant, they sell wholesale to the Pinehurst Resort, Pine Needles, Restaurant 195 and various retirement homes. “We do a lot of brioche and burger buns for food trucks. The biggest thing is that we — all the restaurants here in town — work really hard to be special,” says Brunner. “If I can add a burger bun that I only make for you and you’re going to put your signature burger on it, that’s what we’re all about. We don’t mass-produce.”

Ronnie and Denise Williams

Ronnie and Denise WilliamsBlack Rock Vineyards

Full-time landscapers, Denise and Ronnie Williams branched out from dogwoods and maples to chambourcin and traminette. Grapes, that is. “We have a nursery farm with ball and burlap stock on it. Machine dug trees. We cleared a piece of our property to put in more of the same,” says Denise. “It was not suitable so we started researching what would grow. We kind of got into the grape-growing business. We were told it wouldn’t work here. We started ripping the soil and getting everything ready in 2004. We made our first wine in 2008. We weren’t even hobbyists. We took that first little crop and we sold 1,000 bottles. The next year we made about 3,600 bottles. In 2010 we had our best year, which was about 10,000 bottles.” Now they have 5 1/2 acres of viniferous grapes and sell wine at the Corner Store in Pinehurst and Nature’s Own, in addition to their winery on U.S. 15-501. “The last couple of years have been very challenging because of the weather conditions,” says Denise. “Twice now we’ve lost vines due to cold.” With Ronnie doing the planting and Denise the winemaking — she had a background in laboratory work from a 24-year career at the Pinehurst Surgical Clinic — they experienced some early hurdles and early successes. “We do have some wines that we pulled back,” says Denise. “But we’ve also got some wines that we’ve won medals with. We’ve won medals with our chambourcin. It’s probably our best-seller. It makes a really good medium-bodied wine. It goes really well with barbecue, with a steak. We try to use the minimalist approach to just about everything. We use the least amount of sulfites. We do it in a primitive way. We pick the grapes, bring them back to the warehouse. We have a ratchet press that’s manned by four people.” The winery doubles as an event venue. They’re in the livestock business, too. “We have lamb now,” says Denise. “In Australia they put sheep in the vineyards to mow. Filly and Colts has our racks of lamb on their menu.” The weather extremes of the last few years have cut precipitously into the harvest. “When you lose, it’s heartbreaking,” says Denise, “but it doesn’t keep us from wanting to go forward.”

Rich Angstreich

Rich AngstreichJava Bean Plantation & Roasting Companys

It’s kind of The Comedy Store of coffee shops. Rich Angstreich brings skill to coffee bean roasting and roasting to customer relations. “Friends of mine opened the shop and eventually I became a partner,” says Angstreich, who took over three years after it opened in 1996. At first blush, roasting the green beans was a craft in the making. “It was all trial and error in the beginning because it was just for fun. It took a while but we figured it out. A couple of visits from the fire department,” he says (comedic drum snare). Though the list of coffees fluctuates, beans currently on the docket include Colombian organic, Sumatra organic, Costa Rican, Mexican Chiapas, Honduran and a Sumatra decaf. “We’re definitely small batch, artisan roasting,” he says. Angstreich roasts for the Java Bean, The Bakehouse and Chef Warren’s. Most of his supply comes from a large importer, Royal Coffee, though he also purchases from a small company in Raleigh that deals directly with farmers. “It’s Honduran and they’re trying to expand and get a couple more coffees from Central America,” he says. “Each coffee roasts slightly differently. Some taste better when they’re dark roasted, some taste better when they’re a little lighter roast. We do everything by hand. There are no electronics to start or stop it. Everything is your eyes and your ears and your nose to figure out what to do.”

Hanse and Wagner reshape Pinehurst’s No. 4 course

By Lee Pace

The bar was set quite high indeed for this new No. 4 golf course at Pinehurst Country Club when it opened in 1919, commissioned by Pinehurst owner Leonard Tufts and designed by the Scottish architect Donald Ross.

“It is perhaps the best laid-out course of the whole bunch, and when more thoroughly trapped will tax the skill of the wariest golfer,” noted the Pinehurst Outlook in early December 1919.

Later in the month, the newspaper added: “Mr. Ross is warm in his praise of the No. 4 course which is now a complete eighteen hole affair, and he states that he considers it will be the best golfing proposition of all when it has been fully trapped and the fairgreens developed.”

Best golfing proposition? Lofty praise indeed, though admittedly coming well before the No. 2 course was expanded, revised, remodeled and amped up in the mid-1930s when the prideful Ross was irked of hearing about some upstart course in Augusta, Georgia.

The No. 4 course followed the opening of No. 1 in 1899, No. 2 in 1907 and No. 3 in 1911. From the main clubhouse, No. 3 was set essentially to the west, across Hwy. 5, No. 1 to the south, No. 2 to the east, and No. 4 was tucked to the southeast between No. 2 and 1, much as it is today. Maps indicate that in the very early days of No. 2, three holes peeled off from what is now the 10th green and ran into an area that would later comprise No. 4, then rejoined the current routing at the 11th hole. The large 5-acre lake that has been the primary visual feature was originally much smaller.

No. 2 evolved into its status as one golf’s grandest venues when Ross arrived at its current routing in 1935 and replaced the sand/clay greens with Bermuda grass, and it was deemed at nearly 7,000 yards to be one of the strongest, most severe tests for the elite golfer. It has remained so over nearly a century and in the last two-plus decades has hosted three U.S. Opens and a U.S. Women’s Open.

But being the last to arrive, No. 4 was the first to stumble when difficult economic times arrived in the 1930s, the first domino falling in what would become a checkered existence.

The Tufts family closed nine holes of the course in 1936 and shut down the remaining nine in 1939. Then, when better times arrived after World War II, Richard Tufts, Leonard’s son who had now ascended to the presidency of Pinehurst Inc., tweaked nine of the original holes and they were opened back in 1950. A complete 18-hole course followed three years later.

When the Diamondhead Corporation, Pinehurst’s new owners, enticed the PGA Tour to hold a 144-hole event at the club in 1973, a second course was needed as a venue along with No. 2, and Robert Trent Jones, who had become a Moore County landowner with a parcel bordering Pinehurst Country Club and the Country Club of North Carolina, was retained to lengthen and strengthen the course for the professionals. Then a decade later, son Rees Jones authored yet another renovation — the crux of the project the rebuilding of all the greens to be more receptive to the longer tee shots his dad had integrated years before.

“No. 4 had become a hybrid of designers and ideas with no thread to tie it all together,” Pat Corso, Pinehurst’s president and CEO from 1987-2004, said in 1998.

As he spoke, Tom Fazio and his team were busy at work rebuilding and shaping the course toward yet another iteration. The new No. 4 that opened in December 1999 was routed through essentially the same corridors as the earlier course, but holes were rearranged and Fazio integrated a British flavor of a myriad of pot bunkers as a nod of the cap to Ross, the Scottish designer.

The course also embraced the design flavor of the era: It was green, and it had smooth, soft edges, and there were flower beds in several nooks and crannies, most notably the slopes around the green of the par-3 fourth hole.

All of that was fine until 2011, when No. 2 next door was given a new set of bones and coat of paint courtesy of the design team of Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw. The Deuce had also become sleek and glossy in the golf world’s creep toward the standards set by Augusta National. Don Padgett II, the Pinehurst president and COO at the time, slammed on the brakes and charged Coore and Crenshaw to return the club’s pride and joy to its sandy, linksy, disheveled self that Ross had molded with his native Scotland in mind.

The more No. 2 has succeeded over a half dozen years from contexts of visuals, playability, maintenance and fidelity toward Pinehurst’s past, the more No. 4 paled by comparison. Thus the decision in 2016 by Pinehurst owner Robert Dedman Jr. and Tom Pashley, who succeeded Padgett in 2014, to hire Gil Hanse and partner Jim Wagner to rebuild No. 4. The course closed in October 2017 and Hanse set about his face-lift, his sleeping quarters over the winter being the Ross Cottage by the third hole of No. 2. The new course was sodded and sprigged by early June, and this month is growing in toward a September reopening.

“It all started with Coore and Crenshaw,” Hanse says. “They were brought in to bring back the character and to restore the sandy waste areas and Ross’ vision for what Carolina Sandhills golf looks like. We’ve carried that a little further in this presentation. It’s not a tribute course to Ross or course No. 2. But we feel it will be a good companion golf course.”

The corridors from the old course were used but several shifts in holes were made. Two of the par-3s have been altered substantially. The green on the fourth hole has been moved from well below the tee and beside the lake to a higher elevation farther to the left, with a sharp slope now cascading to the right toward the water. The sixth green was elevated and substantial sandscaping integrated around it. The old 12th hole was abandoned in favor of a new par-3 built into the woods, sitting in a triangle between the previous seventh, 10th and 11th holes.

“The characteristic about No. 4 that is most special is the land. It has some of the most dramatic contours on the entire site,” Hanse says. “On No. 2, holes four and five and 13 and 14 are the most dramatic in terms of topography. I think we’ve eight or nine that have that element. That gives us the opportunity to create very dramatic landscaping and more picturesque landscaping. The new course has something of the look and feel of No. 2 and returns a more natural connection to the landscape.”

Another interesting twist is creating a massive waste area on the par-5 ninth hole similar to the “Hell’s Half Acre” at Pine Valley. Golfers will traverse a sandy area dotted with wiregrass, broom sedge and other wild growth for some 80 yards on their second shot.

The designers and their construction company transplanted thousands of wiregrass plants from the site of the abandoned Pit Golf Links on N.C. 5 near Aberdeen and also moved “chunks” of dirt, sand and vegetation from the site as well. They scooped out sections of ground roughly 2-feet wide by 4-feet long, moved them intact to the No. 4 course and placed them around bunkers. Then a shaper followed and tucked them into the surface, the result hopefully looking like ground that has aged and weathered for years.

Just like No. 2 looked after Coore and Crenshaw took aim in 2010-11.

Just like Mid Pines, another Ross relic from the 1920s, looked after Kyle Franz restored it in 2013.

“What Jim and I focused on was creating something that is going to look and feel and be sort of philosophically in line with the playable characteristics that Ross embraced at Pinehurst,” Hanse says. “The golf course will capture more of that look, that look that Kyle Franz did at Mid Pines. There is an excitement around Pinehurst about recapturing that ‘Pinehurst look.’”

Noting that at Pinehurst “our history is our road map to the future,” Pashley adds that a halfway house will be built alongside the fifth hole of No. 4 and will also serve golfers coming off the 10th green of No. 2 nearby. The architectural model will be the original Pinehurst clubhouse from 1900 — two stories with an observation deck. Coming full circle seems to be an enduring theme at Pinehurst. PS

Author Lee Pace wrote extensively of the Coore and Crenshaw restoration of Pinehurst No. 2 in his 2012 book, The Golden Age of Pinehurst — The Rebirth of No. 2.

An ode to the road

By Susan S. Kelly

It’s a universal truth of summer in North Carolina, when the beach and the mountains become our magnetic poles, that sooner or later you’re going to be traveling on Interstate 40. Or “Forty,” as its fans and its haters call it.

I’m a fan.

You can have your backroads. How can a pastoral scene compare with the racetrack of 423.6 miles that (somewhat) horizontally slices the state? Every mile is pure entertainment. Sure, the “Bridge Ices Before Road” signs get boring, but the stuff people are hauling more than compensates. Where else but on I-40 in North Carolina can you find Christmas trees and golf carts and watermelons and boats? Plus, skis, surfboards, bicycles, kayaks, coolers, tobacco, cotton, horses, coonhound cages, Airstreams, and the requisite pickup or two hauling a chest, a mattress, a La-Z-Boy, and a fake tree, tarp a’ flappin’. It must be admitted that when I pass one of those silver-slatted semis, I strain to see if there are hogs inside, just before I avert my eyes and try not to think about their ultimate destination. Same for the vanilla-colored school bus whose sides read “Department of Prisons.” Don’t tell me you haven’t tried to peer into those windows crisscrossed with wire. I grew up with a father who always pointed out the guy with the rifle on his shoulder while inmates worked on the roadsides. Don’t see that much anymore, or those silvery mud flaps sporting silhouettes of naked ladies. Now the rigs are hot pink, for breast cancer. Progress.

I’m not the slightest bit offended if a rig driver honks at me as I pass. If someone still finds my 63-year-old knees attractive, I ain’t complaining.

How does a town get a name like Icard?

I particularly like those lead drivers with flashing head and taillights that warn of “Wide Load.” What a cool job. Like Dorothy Parker, who famously said that she’d never been rich, but thought she’d “be darling at it,” so would I in one of those cars. Think of the books-on-tape you could finish.

The amazing variety of stuff dangling from rearview mirrors — sunglasses, leis, air fresheners, Mardi Gras beads — all give a glimpse into a driver’s personality, like bumper stickers. (Question: How did so many Steelers fans wind up in North Carolina?) And while Virginia holds an unofficial record for vanity tags, I-40 is no slouch in that department, either. PRAZGOD. KNEEDEEP. IAMAJEDI. JETANGEL. Hair seems to be an ongoing tag topic: HAIRLOOM. NOHAIR. And this: SPDGTKT. Seriously, why not just call the cops instead of advertising?

I do not understand convertibles on interstates.

Do not fret yourself over aliens and vampires: If I-40 traffic is any indication, white pickup trucks are far more likely to take over the world.

You can’t fail to notice, while the Athena cantaloupes you bought at the state farmers market are growing more and more fragrant in the backseat, that, let’s face it, the flowers and trees planted in medians around Raleigh are way more attractive than anywhere else in the state. Harrumph. Near Fayetteville, D.C. license tags get more numerous, just as around Asheville, the Tennessee tags multiply, and around Benson, the New Yorks and Floridas proliferate.

Granted, I’d swap a few Bojangles and Cracker Barrel signs for South of the Border and Pedro puns on I-95, but that Mobile Chapel — a permanent trailer in the parking lot of a truck stop near Burlington — never fails to intrigue. As does Tucker Lake, a Johnston County curiosity with a fake beach and so kitted out with rope swings, slides, ski jumps, cables and random docks that you can scarcely see the water. Moreover, a stretch of I-40 around Greensboro has its own ghoulish nickname — “Death Valley” — for its unfortunate statistic of wrecks. And how about those cell towers disguised as pine trees? Come on. The “trees” are so spindly that they look like they belong, well, somewhere near the actual Death Valley.

So much to see from mountains to coast. What you won’t see, though, is the sign where I-40 begins, in Wilmington, that reads “Barstow, California 2,554 miles.” It was stolen so often that the DOT got tired of replacing it. Meanwhile, if you happen to have a list of locations for the elusive Dairy Queens along I-40, please text me. Calories don’t count when you’re a friend of Forty. PS

Susan Kelly is a blithe spirit, author of several novels, and proud grandmother.

NONFICTION

Indianapolis: The True Story of the Worst Sea Disaster in U.S. Naval History and the Fifty-Year Fight to Exonerate an Innocent Man, by Lynn Vincent and Sara Vladic

Vincent, the co-author of Same Kind of Different as Me and Heaven is For Real, teams up with Vladic to re-examine the story of the Indianapolis. Thanks to a decade of original research and interviews with 107 survivors and eyewitnesses, Vincent and Vladic tell the complete story of the ship, her crew, and their final mission to save one of their own — the fight for justice on behalf of their skipper, Capt. Charles McVay III, who was put on trial as a scapegoat for the infamous and unforgettable moment in American naval history.

Jell-O Girls: A Family History, by Allie Rowbottom

After her great-great-great-uncle bought the patent to Jell-O from its inventor for $450, Rowbottom reveals the dark family history that flowed from one of the most profitable business deals ever. Jell-O Girls is a family story, a feminist memoir, and a tale of motherhood, love and loss. In crystalline prose, Rowbottom considers the roots of trauma not only in her own family, but in the American psyche, ultimately weaving a story that is deeply personal, as well as deeply connected to the collective female experience.

Killing It: An Education, by Camas Davis

A longtime food writer, Davis delivers a funny, heartfelt memoir of her journey from a girl without a job, home or boyfriend in Portland, Oregon, to rural France, where she learned the artisanal craft of an enlightened butcher. When Davis returns to Portland, the city is in the midst of a food revolution, where it suddenly seems possible to translate much of the Old World skills she learned in Gascony to a New World setting. Camas faces hardships and heartaches along the way, but in the end, Killing It is about what it means to pursue the real thing and dedicate your life to it.

Northland: A 4,000-Mile Journey Along America’s Forgotten Border, by Porter Fox

Spending three years exploring the border between the United States and Canada, traveling from Maine to Washington by canoe, freighter, car and on foot, Fox blends a deeply reported and beautifully written story of the region’s history with a riveting account of his travels. Fox follows explorer Samuel de Champlain’s adventures across the Northeast; recounts the rise and fall of the timber, iron and rail industries; crosses the Great Lakes on a freighter; tracks America’s fur traders through the Boundary Waters; and traces the 49th parallel from Minnesota to the Pacific Ocean.

City of Devils: The Two Men Who Ruled The Underworld of Old Shanghai, by Paul French

Set in a city of temptations, French tells an astonishing story of the two men whose lives intertwined in both crime and a twisted friendship. “Lucky” Jack Riley, with his acid-burnt fingertips, finds a future as The Slots King while “Dapper” Joe Farren, whose name was printed in neon across the Shanghai Badlands, rules the nightclubs. Eyewitness accounts from moles at the Shanghai Municipal Police, letters and contemporary newspaper articles inform this meticulously researched story, bringing to life the extravagant music halls, bars, theaters and political unrest of a city that appears both intensely glamorous and depressingly seedy.

FICTION

The Family Tabor, by Cherise Wolas

The beloved author of The Resurrection of Joan Ashby returns with a second novel. A family patriarch’s forthcoming award as Man of the Decade causes his wife and adult children to re-examine their choices, and the parts of themselves they share with family members in an engaging and remarkable work of literary fiction. The author will be in Southern Pines on July 25th.

Dear Mrs. Bird, by A.J. Pearce

British women’s magazines during World War II published articles about making do, keeping calm and carrying on as well as answers to queries about trivial events or how to cope when bad things happen. Dear Mrs. Bird tells the story of Emmy, who opens the mail addressed to the advice column at a magazine, and the events that unfold when she writes her own reply to one of the letters. If you loved Major Pettigrew’s Last Stand, The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, or the Miss Read books, you will adore this book.

Clock Dance, by Anne Tyler

Willa Drake can count on one hand the defining moments of her life. In 1967, she is a schoolgirl coping with her mother’s sudden disappearance. In 1977, she is a college coed considering a marriage proposal. In 1997, she is a young widow trying to piece her life back together. And in 2017, she yearns to be a grandmother but isn’t sure she ever will be. Then, one day, Willa receives a startling phone call from a stranger. Without fully understanding why, she flies across the country to Baltimore to look after a young woman she’s never met, her 9-year-old daughter, and their dog, Airplane. Surrounded by eccentric neighbors who treat each other like family, she finds solace and fulfillment in an unexpected place.

Who Is Vera Kelly, by Rosalie Knecht

New York City, 1962. Vera Kelly is struggling to pay the rent and blend into the underground gay scene in Greenwich Village. She’s working night shifts at a radio station when her quick wit, sharp tongue and technical skills get her noticed by a recruiter for the CIA. Next thing she knows she’s in Argentina, tasked with wiretapping a congressman and infiltrating a group of student activists in Buenos Aires. As Vera becomes more and more enmeshed with the young radicals, the fragile local government begins to split at the seams. When a betrayal leaves her stranded in the wake of a coup, Vera learns the Cold War makes for strange and unexpected bedfellows, and she’s forced to take extreme measures to save herself.

Doll-E 1.0, by Shanda McCloskey

Curious, inquisitive, confident Charlotte is always tinkering, coding, clicking and downloading. So when she gets a doll for a gift, what does she do? She tinkers, codes and clicks, and creates the new Doll-E 1.0. A celebration of science, creativity and play, Doll-E is the perfect book for budding young scientists who also love Rosie Revere. (Ages 3-7.)

Albert’s Tree, by Jenni Desmond

Who wouldn’t just adore sweet Albert! Concerned about why his tree is crying, Albert the bear sets out to solve the mystery and what he discovers surprises everyone. A great read-aloud, Albert’s Tree will become a favorite read-it-again story for young nature lovers. (Ages 3-6.)

Smack Dab in the Middle of Maybe,

by Jo Watson Hackl

Quirky charming Cricket Overland wanders out of Thelma’s Cash and Carry Grocery Store and into the hearts of readers who have loved Three Times Lucky, Savvy and The Penderwicks. Armed with only a few snacks, a hand shovel, duct tape and a live cricket named Charlene, Cricket sets out on her own to find some answers. A sweet, clever, stand-alone adventure story with an art history/mystery twist thrown in for good measure. (Ages 8-12.)

Furyborn, by Claire Legrand

Two young women, Rielle and Eliana, living centuries apart, tap into their extraordinary personal powers when someone close to them is threatened. As they fight in a cosmic war that spans millennia, their stories intersect, and the shocking connections between them ultimately determine the fate of their world — and of each other. Bloody, violent, fast-paced and impossible to put down, fantasy fans everywhere will consider Furyborn a must-read for the summer.

(Ages 14 and up.) PS

Compiled by Kimberly Daniels Taws and Angie Tally.

The king of herbs spices up summertime

By Jan Leitschuh

Many of you are eaters of fresh produce, not growers. I get that.

However, if you grow nothing else, you can grow basil. Fresh basil is the classic fragrance of a foodie’s hot-weather feast, the symphonic notes in the Sandhills’ summer bounty. Food writers call basil “The King of Herbs” for the commanding accent it brings to seasonal food.

A cool plate of juicy heirloom tomatoes sliced simply with fresh mozzarella and topped with fresh basil, cracked pepper and balsamic is about as good as it gets in July. Unless, of course, it’s a fresh peach, goat chèvre and basil salad . . . or a pizza margherita with fresh basil leaves . . . or basil chicken with lemon . . . or a cucumber, basil and lime gimlet . . .

You see? No mention yet of pesto, which is delicious nonetheless.

Yes, you non-kitchen-gardener you, you can grow basil. Just buy a 4-inch pot and set it in a window box. Or in a planter. Tuck a plant outside your back door, right in the dirt. In fact, if you have a sunny window, you can even grow it indoors. The store-bought fresh packs are convenient but costly, and, if you are a basil lover, insufficient. Just grow some already.

For so much flavor, basil’s wants are simple: sunshine and lots of it. And warmth. Water when the soil gets dry which, in a full-on Sandhills summer, can be daily.

With a little pinching — or rather, harvesting — of a few pungent, glossy leaves, sweet basil will grow into a vigorous bushy ball, about a foot or two high.

And while we savor the Mediterranean notes that basil brings to our summer tables, it turns out it’s also a very healthy addition to our diets. Basil is a brain enhancer. Certain antioxidants in basil are considered protective shields for the brain, preventing oxidative stress. Eating basil, which contains minerals like manganese, may be useful in preventing cognitive decline.

Anti-inflammatory elements of basil help quell the burning of arthritis, or soothe the acid indigestion you’ll surely get from scarfing that whole pizza pie. A great source of vitamin K, basil also helps build strong bones, and its phenolics and anthocyanins make it a useful addition to a cancer-fighting diet.

Beyond the sweet or Genovese basils, you can find the beautiful purple-leaved basils such as Red Rubin and Dark Opal. These dark lovelies are garden accents in and of themselves. Other cultivars are available with different tastes, including cultivars with cinnamon, clove, lemon and lime notes. Holy basil, or tulsi, is another flavor altogether. Start with the tried and true sweet basil, and branch out from there.

Potted plants are readily available in the spring, but basil is easy and inexpensive to start from seed. Press a few seeds into a pot and water. You can do this monthly to ensure a continuous supply.

As the daylight shortens, your basil will try to flower. Pinch these off immediately. You are trying to keep it in the fragrant vegetative (leafy) state, not allowing it to send its energy into reproduction (flowers and seeds).

To keep cut basil fresh in your kitchen, treat it like the lovely bouquet it is. Trim the stems and put them in a jar or glass of water on your counter. Cover it with a loose plastic bag if you want. Never put fresh leaves in the fridge, where they will blacken.

At some point in the summer, you will have a lot of basil. This is a good thing, as Martha Stewart would say. Think ahead to those basil-less winter pizzas, fish dishes and pastas (sad trumpet sound). How do you think pesto got invented? It uses scads of basil. If your summers are busy and you don’t have time to combine with pine nuts or walnuts, and pecorino cheese, just rinse off a batch and whir it with simple olive oil. Freeze in ice cube trays and re-bag. Pull out a basil cube on a joyless, sunless winter day when you need to remember the sunshine.

Or, using the bounty of July, serve up something cool:

Tomato, Basil and Watermelon Skewers

Alternate squares of watermelon with feta squares, basil and halved cherry tomatoes.

Arrange on a platter, drizzle with EVOO and a good balsamic vinegar. Have a party and share the flavor. PS

Jan Leitschuh is a local gardener, avid eater of fresh produce and co-founder of the Sandhills Farm to Table Cooperative.

Especially on a hot summer afternoon

By Deborah Salomon

The heat of July, always a scorcher, means gallons of cold stuff to wash down the potato salad. And, because in these parts nothing goes down easier than Retro-Ade, let me dig around in the cooler for some thick glass bottles filled with . . .

I spent every hot, dusty summer of my childhood at my grandparents’ house, in Greensboro, which my mother thought was preferable to hot, muggy summers in Manhattan. No residential AC in the 1940s, but you could sit the afternoon in a frigid movie theater, since movies ran continuously and kiddie fare was a dime. The other good thing about Greensboro was soda. My mother forbad it at home, a punishment for not liking milk, unless mixed with Jell-O pudding or Campbell’s Tomato Soup. For a special treat, a few times a year I was allowed a fountain Coke over shaved ice at the drugstore, only because she loved them. But my sweet Nanny Teachey knew that little girls need a cold bottle of fizzy to make long, hot afternoons bearable. That bottle came from the mom-and-pop grocery on the corner which, like the gas station up the block, had a massive cooler with a bottle opener attached. I see them in antique shops now, and weep.

Nanny would grab her shopping bag, wink at me and say, “Come keep me company while I walk up to the store.” I never got why she needed an item or two every day.

Once there, she slipped me a nickel and let me choose from glorious Dr. Pepper, Coca-Cola, Grapette, Nesbitt’s Orange, Royal Crown. The bottles were much smaller and scratched from re-use. A plain white paper straw touched the bottom with plenty of sipping room up top. Grapette was my favorite, deep purple, in a clear glass bottle. Who knows if it contained even a drop of fruit juice? I was in heaven. To make it last I slipped the cold bottle under my shirt on the walk home, then hid it beside my bed.

Nesbitt’s Orange was my second favorite because the bottle was bigger, except even with a straw, the orange artificial color left me with a tell-tale neon tongue. Then, the ultimate: Nanny froze Pepsi in an aluminum ice tray. I’d chop the cubes into slush and eat with an iced tea spoon.

Calories and high fructose corn syrup weren’t factors, just blistering July heat and a cold soda.

About once a week Nanny and I returned bottles for the deposit, usually when my mother had gone uptown to the beauty parlor, or else she might wonder how so many had accumulated; during our visits the only soda allowed at the table was Canada Dry Ginger Ale, which Granddaddy put in his iced tea instead of lemon. Nanny carried the heavy bag but I inserted the empties in a metal rack beside the cooler, producing a clink I haven’t heard for 70 years.

Well, guess what? Grapette changed hands, went underground but survived and is now part of Walmart Sam’s Club beverage line, in a 2-liter plastic container. No thanks. I only want a little, sucked with a straw from a scratched bottle — so cold it made my head ache, so clandestine that the chill produced a wicked thrill.

I don’t drink soda anymore except for the occasional Fresca. Too many chemicals. Besides, my apartment is air conditioned and “purified” water’s all the rage. As for those sickly sweet caffeine-laced fondly remembered concoctions, they wouldn’t be much good at washing down brown rice and sautéed kale.

To everything, a season. You can’t go home again and other platitudes. I don’t want to, because memory glorifies and reality disappoints. But when thirst overtakes me on a July afternoon . . . PS

Deborah Salomon is a staff writer for PineStraw and The Pilot. She may be reached at debsalomon@nc.rr.com.

In search of the rare grasshopper sparrow

By Susan Campbell

One of the rarest breeding birds here in the Piedmont is the grasshopper sparrow. This diminutive, cryptically colored bird can only be found in very specific habitat: contiguous, large grassland. Such large fields are increasingly hard to find across our state these days. And even if you seek out the right habitat, seeing an individual, even a territorial male, is not very likely because they are so secretive and well camouflaged. But if you persist, you might hear one of them. Their voices are quite characteristic: a very high-pitched buzzy trill. It is the combination of their call and the typically grasshopper-rich areas in which they are found that gives them their name.

Nowadays these birds are only found in manmade grasslands. In the Sandhills, the only location where they breed is at the Moore County Airport. I have identified as many as 12 grasshopper sparrow territories between the runway and Airport Road. I suppose some birds may use what are called drop zones, areas targeted for paratrooper operations at Fort Bragg. However, these typically have a variety of plants — not ideal territory for these birds. Up around Greensboro, I hear that they can be found scattered among the agricultural fields along Baldwin Road. If you make the trip, also be on the lookout for a dickcissel, a fairly, large, yellowish sparrow-like individual that is even, an even rarer find.

Grasshopper sparrows return from their wintering grounds in Mexico and the southeastern coastal plain of the United States by mid-March. Males spend much time singing from taller vegetation, often beginning their day well before dawn. They use short, low fluttering flight displays to impress potential females. Eggs are laid in cup-shaped nests in a slight depression, hidden by overhanging grasses, containing four or five creamy-colored eggs that are speckled reddish-brown.

Habitat loss has certainly affected the small local populations of these birds, plus routine mowing of these fields usually destroys nests. But the birds stay and attempt to nest again. In shorter grass, their nests are easily detected by predators, such as foxes and raccoons. Therefore, breeding success tends to vary greatly from year to year in these types of locations. If the habitat remains unaltered from May through August, grasshopper sparrow pairs can produce two (and sometimes three) families in a year.

But these birds are also vulnerable to the effects of pesticides. Although they do eat small seeds associated with the grasses that grow around them, they also rely upon significant numbers of insects, especially when they are feeding young.

Grasshopper sparrows are surely not easy to observe in summer but, in winter, they are even harder to find. They mix in with other sparrows that frequent open spaces and seldom sing. But for those experienced birdwatchers who enjoy the challenge that comes with sorting through “little brown birds,” (like me!), their flat foreheads, large bills and buffy underparts are a welcome sight. PS

Susan would love to receive your wildlife sightings and photos. She can be contacted by email at susan@ncaves.com.