Amelia Earhart, George Putnam and their high-flying love affair

By Bill Case

They called it an autogiro. This unusual flying machine was something of a hybrid between an airplane and a helicopter. Like an airplane, it possessed wings and a propeller. But the wings were so stubby, they seemed a design afterthought. While resembling a helicopter with its horizontal rotary blades whirling atop, the aircraft was powered differently. It did not fly very fast — typically 80 miles per hour — and held only enough fuel to safely fly two hours at a stretch. But, flown by a proficient pilot, it could take off and land in an area no bigger than a suburban back yard. Before November 11, 1931, it is doubtful anyone in Moore County had observed, in flight, an aircraft requiring virtually no runway for its operation. That was one reason why on an Armistice Day mid-afternoon, well over 1000 people flocked to the dirt and grass airstrip known as Knollwood Field (now Moore County Airport) to hail the arrival of an autogiro.

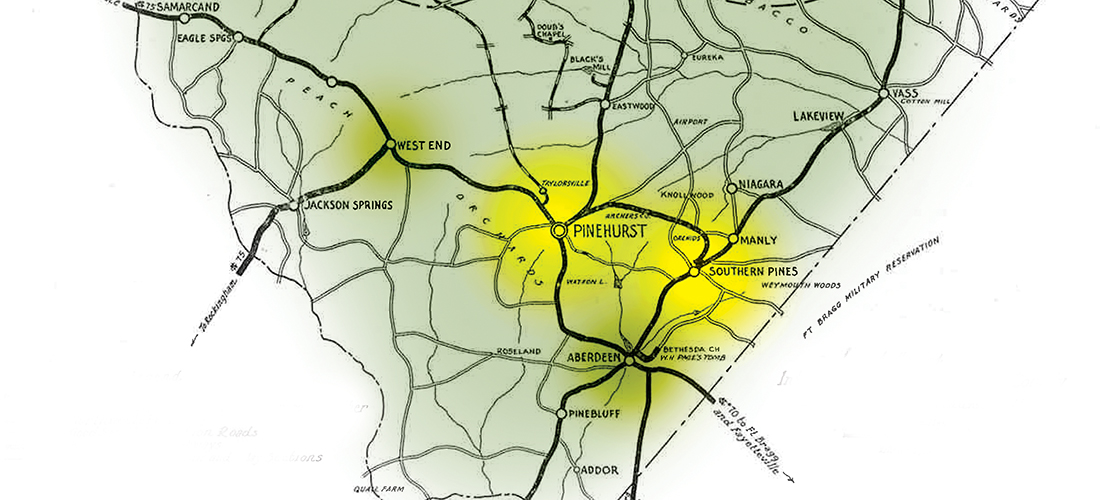

Despite its novelty, such a sighting wouldn’t ordinarily have created such a stir that stores and schools in Pinehurst, Southern Pines, and Aberdeen would close. The pilot flying the aircraft was the one causing most of the hubbub — 34-year-old Amelia Earhart, one of the most famous women in America.

It had already been a long Armistice Day for the slender Kansas native. At daybreak, she had flown out of Charlotte, piloting her ungainly aircraft two hours east before setting down in a field five miles north of Fayetteville. Wearing the leather jacket, scarf, jodhpurs, and boots she typically donned in the air, Earhart was whisked by a welcoming committee into Fayetteville’s downtown by open car. There she was feted by thousands of adoring citizens who cheered the waving pilot as she slowly passed by.

At the conclusion of the parade, the soft-spoken but confident Earhart addressed an all-ears crowd at Fayetteville’s Market House, even putting in a good word for the Beech-Nut Packing Company’s chewing gum. George P. Putnam, a promotional genius who was newly wedded to Amelia, had arranged for Beech-Nut to sponsor her three 1931 hopscotching autogiro tours. The company’s emblem was prominently emblazoned on the fuselage. All the fuss in Fayetteville had put her behind schedule as the throng at Knollwood Field waited impatiently to catch sight of Earhart’s “flying windmill” on the horizon.

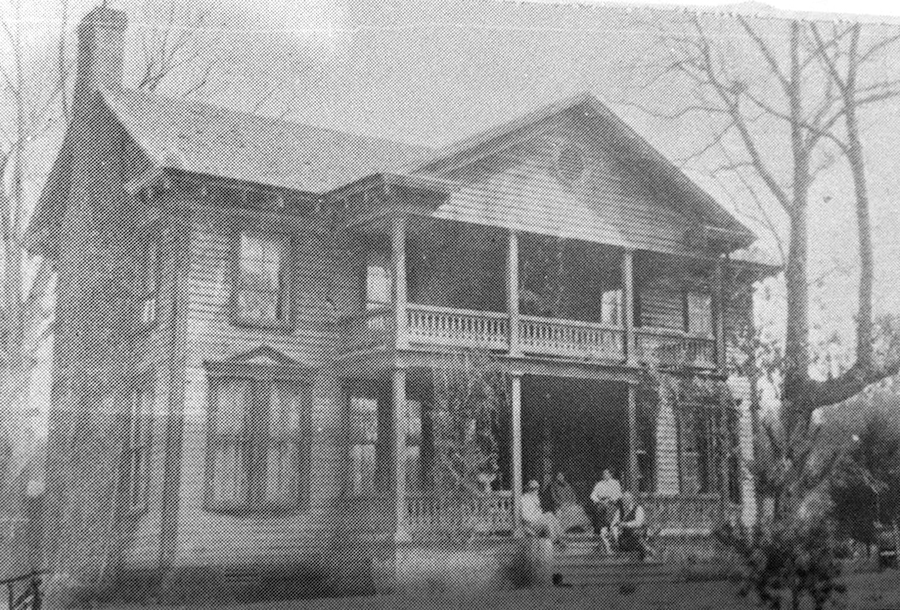

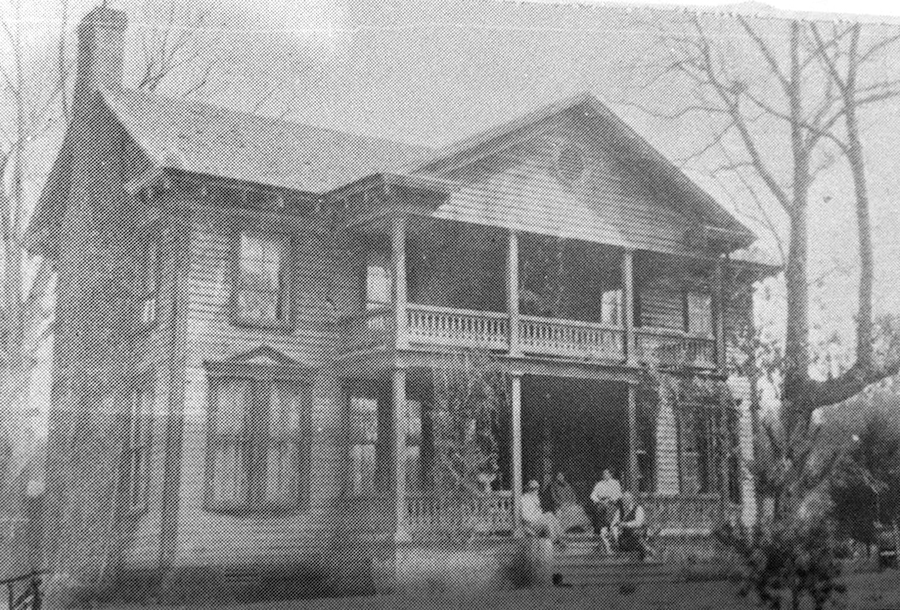

This was the famous aviator’s first visit to Moore County, though her husband was no stranger to the Sandhills. Dorothy Binney Putnam, George’s ex-wife, had spent considerable time here. In fact, until Earhart’s recent marriage to Putnam, she and Dorothy had enjoyed a close friendship, sharing among many things their mutual love of the outdoors. Elegant and statuesque, Dorothy’s affection for the wilderness had been kindled during family vacations near Carthage where in 1901, her father Edwin Binney, the founder and inventor of Crayola Crayons, had purchased a 1,300-acre plantation deep in the pine forest. The property featured a rambling antebellum plantation house with a second floor balcony that provided a magnificent view of the home’s surroundings. The spread was called “Binneywood.” It is uncertain why Connecticut-based Edwin selected Carthage for a vacation home though it probably had something to do with the proximity of the North Carolina mining operations that supplied raw materials for Crayola.

Dorothy Putnam had regaled Earhart with tales of the wonderful times she and her two sisters had enjoyed at Binneywood. Dorothy’s diary entry during the 1908 Christmas season at Binneywood describes an eventful and festive holiday atmosphere: “Up at dawn to go wild turkey hunting. Home at nine, then chopped trees, then quail hunting-good luck. Made fudge and sipped chocolate by fire.”

Despite the estate’s remoteness and their status as seasonal residents, Edwin Binney, known as Bub, and his wife became integral members of the Carthage community. They farmed, planted a peach orchard, reactivated the estate’s milling operation, and hosted country dances at Binneywood featuring rousing strains of banjoes and fiddles.

A particularly splendid event happened at the old plantation during the Christmastime of 1910 when Dorothy, a Wellesley grad, and George Putnam, whom she had met during a two-month western camping trip, announced their engagement. They married the following October. The newly wedded couple spent an extended honeymoon in Central America. Like Earhart, the two adventurers reveled in experiencing exotic and unfamiliar surroundings. The trip inspired Putnam to author his first book, The Southland of North America, with his new wife eagerly collaborating.

Then 24, Putnam had not yet joined the family’s renowned publishing concern, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, deciding instead to publish and edit the Bend Bulletin, a newspaper in faraway Bend, Oregon. It was an ideal place for the Putnams to begin their married life, indulging their penchant for the outdoors with horseback rides and camping trips into the recesses of the Cascade Mountains. Putnam proved to be an independent newspaperman and an advocate for progress by penning editorials urging that women be afforded the vote. He was even elected the town’s mayor. Dorothy also became a force in Bend’s civic life, raising funds for causes ranging from the Red Cross to fighting cancer. A tireless advocate for women’s suffrage, in 1912 she became the second female (after the governor’s wife) to vote in Oregon.

The Putnams’ first child, David Binney Putnam, was born in 1913. Soon thereafter, they moved to Salem, Oregon’s capital, where he took a post as secretary to the state’s governor while still retaining his position as the Bulletin’s publisher. During World War I, Putnam enlisted in the army which resulted in the couple’s moving to Washington, D.C. After his father died, Putnam decided to join the family business and they relocated to Rye, New York where Dorothy bore a second son, George, Jr. (“Junie”) in 1921.

Ensconced with G.P. Putnam’s Sons, George’s career skyrocketed as he became the company’s go-to spokesman. He was increasingly away on an unceasing quest to unearth new stories. Longing for adventures of her own, Dorothy seized the opportunity to travel with son David on a 10-week oceanographic expedition to the South Seas of the Pacific in 1925. She reveled in her role as a scientist on the voyage while 12-year-old David recorded a narrative of his experiences that Putnam published under the title David Goes Voyaging. The book was a surprising hit.

The elder Putnam embarked on his own expedition to Greenland in 1926. “I practiced what I published,” he wrote. David tagged along with his father. The expedition proved a success and provided the fodder for the young teenager’s second book, David Goes to Greenland. A second father-son expedition to Baffin Island followed in 1927 resulting in David’s third book. When he got back, Putnam immersed himself in bagging the rights to Lindbergh’s story for G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Home in Rye, Dorothy stayed socially active, entertaining explorers such as Admiral Richard Byrd. Will Rogers said that one “couldn’t snare an invitation [to Dorothy’s parties] unless you had conquered some uncharted territory.” But she was restless and bristling at being the one generally left behind to tend the home fires. With all the time apart, the couple increasingly led separate lives and the ties of their union began to unravel.

Still vibrant at age 38, Dorothy yearned for passion in her life. She found it in 1927 in the person of George Weymouth (“GW” in Dorothy’s diary), a handsome and polished sophomore at Yale who had been tapped to tutor David at home. Though guilt-ridden by her infidelity, Dorothy nevertheless thought it unjust that men usually got a pass. “Why is it there are so many men who consider love outside the bonds of matrimony the privilege of the male only?” she asked in her diary. When Dorothy discovered evidence that her husband was also having an affair, she penned that his dalliance lightened “my sense of fidelity.” Dorothy’s affair with GW was in bloom at the time Amelia Earhart came into the Putnams’ lives.

Earhart’s unlikely emergence occurred in 1928 in the wake of Charles Lindbergh’s historic flight. An American heiress, Amy Phipps Guest, made it known she was personally bankrolling the first flight across the Atlantic with a woman onboard. Guest acquired a Fokker plane and rechristened it the “Friendship.” Then she set about finding the right female to make the journey.

When George Putnam got wind of Guest’s quest, he offered to take charge of the search. If Putnam could position himself as the one to choose the candidate, his publishing company would have the inside track on the woman’s story. Having already enjoyed remarkable success promoting non-fiction first-person adventures, including Byrd’s Skyward and obtaining the rights to Lingbergh’s story, the gambit was right up Putnam’s alley.

Earhart was a natural candidate. She had learned to fly in 1921 while living in Los Angeles. She was particularly attracted to the challenge of achieving aviation “firsts.” Two years after her first flying lesson, Amelia established a new high altitude mark. She’d also flown in air shows. In 1923 the young pilot became the first woman granted a certificate by the aeronautics branch of the Department of Commerce, the precursor of the Federal Aviation Administration. After moving to Boston in 1928, Earhart joined the local chapter of the National Aeronautic Association. When George Putnam summoned her to New York in May 1928 for the most important interview of her life, she was leaving behind a job that had nothing whatsoever to do with flying. She was employed as a social worker at Boston’s Denison House.

The attraction was nearly instantaneous. “Before I had talked to him for very long I was conscious of the brilliant mind and keen insight of the man,” wrote Earhart. Putnam knew Earhart would be perfect for the “Friendship” flight. Not merely a proficient pilot, she was a promoter’s dream. Slender, with short curly blond hair, she was attractive in a tomboyish yet feminine way. Another bonus was the young woman’s uncanny resemblance to Lindbergh —not just physically, but also because of her direct but soft-spoken manner. Soon the announcement came that Earhart had been chosen. Delayed two weeks by poor weather, the venture’s participants, chief pilot Bill Stultz, co-pilot Slim Gordon, Earhart, and Putnam were forced to hole up in Boston’s Copley Plaza Hotel to wait out the storm.

Putnam asked his wife to join the group. He figured Dorothy’s adventurous, free-spirited personality would make her a conversational match with Amelia. His assessment proved correct. The two chatted like schoolgirls concerning their shared interests in theatre, literature, fishing, and horseback riding. Finally the weather cleared and the “Friendship” was aloft. The flight turned out to be most challenging. An engine kept cutting out and the crew lost their radio connection. “Friendship” was blown off course, and even before land was sighted the engines began sputtering as they ran short of gasoline. Though Bill Stultz thought he was landing in Cornwall, it was actually Wales, but the plane and crew had arrived safely.

Though she had been little more than a passenger, the flight catapulted Earhart into stardom. It was the beginning of a life loaded with personal appearances, parades, and speeches. After celebratory tours, first in England and then America, she holed up in Rye at the Putnam home adjacent to the posh Apawamis Club’s golf course. Under George’s direction, she commenced writing the book that would be called 20 Hrs., 40 min.: Our Flight in the Friendship.

Aviation’s budding superstar found time for fun in Rye. She and Dorothy shopped, swam, and attended upscale social occasions. It was Dorothy, not George, to whom Amelia dedicated 20 Hrs., 40 min. In her book Whistled Like a Bird — The Untold Story of Dorothy Putnam, George Putnam, and Amelia Earhart,” Sally Putnam Chapman, Dorothy and George’s granddaughter, wrote, “had it not been for my grandparents, Amelia would not have moved in the circles she did.” Dorothy introduced Amelia “to a glittering array of celebrities, artists, adventurers, and socialites.” With her newfound celebrity and the success of her book came financial rewards. It became abundantly clear that Earhart would never return to her previous life at Denison House.

Her relationship with George Putnam was also deepening. Within a month of Earhart’s arrival in Rye, an entry in Dorothy’s diary notes, “George is absorbed in Amelia and admires and likes her. Maybe he’s in love with her.” Eventually, she became convinced that her husband and the flier were “a couple.” Putnam certainly was smitten. His later writings indicate he considered Amelia the epitome of chic. Reminiscing after her death, he wrote, “I think she really did not realize that often she was very lovely to look at.” He gushed about, “her beautifully tailored gabardine slacks,” and “the tapering loveliness of her hands [that] was almost unbelievable.” Apparently Vanity Fair agreed. The magazine shot a fashion spread of Earhart that hit the newsstands in 1932.

Dorothy terminated her ongoing affair with GW in August 1928, although the two remained friendly. Nevertheless, her diary entries do not suggest she yearned to be reconciled with a husband she no longer loved. She broached the subject of divorce and, though George made an attempt to patch things up, that effort seemed halfhearted since he remained in constant contact with Amelia.

By June of 1929, after discovering another affair with Frank Upton, a flier and war hero, Putnam informed his wife that he too wished the marriage to end. Despite the fact that Earhart’s relationship with Putnam had become an open secret, Amelia invited Dorothy to accompany her in July as the first female passengers to fly coast-to-coast in a Transcontinental Air Transport commercial airplane. Pleased to be included as part of an aviation first, Dorothy accepted. She and her husband’s lover remained cordial during their trip. A week later they were together in the Galapagos Islands on a deep-sea dive. That excursion marked the end of their social time together though both women thereafter invariably professed respect and admiration for one another.

After nearly getting cold feet, Dorothy obtained a Reno divorce from George on December 19, 1929. She remarked that day in her diary, “How scared and empty I feel!” She sought to remake her life with her two children and Upton, her new husband, in Fort Pierce, Florida where her father had invested in local real estate. She purged her sadness by building a Spanish-style home on an 80-acre tropical wilderness.

At the time, Earhart told a friend that she was fond of Dorothy and considered the divorce “a shame.” But her primary focus was on bolstering her status as America’s foremost female aviator. She cemented that position with her vagabond solo round-trip transcontinental flight in 1929. Putnam kept her busy at each stop, scheduling lectures, personal appearances, and newspaper interviews. Earhart also started an organization comprised solely of women in aviation which became known as the “Ninety Nines.”

After resigning from the family business and joining another publishing company, George Putnam turned his attention to relentlessly pursuing marriage with Earhart. Reluctant to forego her independence, she turned him down at least twice. In February 1931, Earhart finally accepted his proposal, but with conditions. She wrote to him, “On our life together, I want you to understand I shall not hold you to any medieval code of faithfulness to me nor shall I consider myself so bound to you . . . I must extract a cruel promise, and that is you will let me go in a year if we find no happiness together (and this for me too).” Putnam accepted her terms. Some believe that her mention of an open marriage (as well as a suspected subsequent affair with Gene Vidal, Gore’s father) signaled that the couple’s union was more of a business arrangement than a true romance. But David Putnam later observed, “In the privacy of their home, they [his father and stepmother] were lovingly demonstrative.”

Earhart’s forceful establishment of the marriage’s terms undercut the impression of some that Putnam was the puppet master in the relationship. George himself later acknowledged that often Amelia held the upper hand, writing that she was “endowed with a will of her own, [and] no phase of her life ever modified it, least of all marriage.”

In any event, the newlyweds’ fledgling marriage was off to a good start as Amelia and her autogiro made their way into Moore County airspace. Tightly squeezed into the open cockpit of her Pitcairn PCA-2, Earhart peered through her goggles attempting to locate the airfield. As it was a pet peeve of the aviatrix that many of the new airports sprouting up like spring dandelions lacked identifying signage, Earhart was pleased to spot the word “PINEHURST” displayed in giant letters on the roof of Knollwood Field’s hanger.

The gathered onlookers, including the mayor and commissioners of Southern Pines, representatives of Pinehurst, and Mrs. W.C. Arkell, wife of the Beech-Nut Packing Company vice-president, watched as she flawlessly executed her landing. Perhaps the person most gratified by Earhart’s appearance was the manager of the airport, Lloyd Yost. A celebrated pilot himself, just nine days before, he had instituted shuttle flights from Knollwood Field to Raleigh, boasting that the new shuttle cut travel time from New York to Pinehurst down to six hours. In his wildest imagination, he could never have conjured up better publicity for showcasing the service than having the world famous Earhart drop in. Yost personally greeted his fellow pilot and made certain he was photographed alongside her.

Earhart apologized for keeping everyone waiting and cheerfully set about signing autographs. She did not linger long. Her stop at Knollwood was primarily for refueling with no time allotted for parades or lengthy speeches. Within a half hour she was airborne again. Amelia made good her return to Charlotte and would be back in the air the next morning destined for Spartanburg where thousands more would greet her.

Not one to rest on her laurels, in May of 1932, Earhart emulated Lindbergh’s triumph by becoming the first woman to make a solo flight across the Atlantic. The wind blew against her the entire way and, running low of fuel, she was forced to abandon her planned destination of Paris, landing instead in the field of a nonplussed Irish farmer. Though Amelia’s star had never waned since her “Friendship” flight, her solo trip across the ocean propelled “The Queen of the Air” into a still higher galaxy.

A busy 1933 summer beckoned, what with an upcoming meeting with Eleanor Roosevelt and a transcontinental air race, so George Putnam and his new wife, Amelia, decided to take some time for themselves. The Sandhills drew them back in March when they holidayed together in Pinehurst at the Carolina Hotel. The stay was presumably coupled with a visit to George’s mother who had taken the Schaumberg House on New York Avenue in Southern Pines for the season.

One consequence of the Earhart-Putnam marriage was that George’s two sons, David and George, Jr., developed a mutual affinity with Amelia. In Whistled Like a Bird, Chapman writes, “When the boys visited, she [Amelia] made sure to set aside time for horseback riding, sailing, picnicking, and swimming.” And the Putnam boys happily returned the affection their stepmother demonstrated toward them.

Other notable flights followed for Amelia, but they paled in comparison to the imposing 29,000-mile round-the-world flight she started planning in 1936. After one jettisoned attempt, she tried another in June 1937 with mechanic Fred Noonan aboard her Electra aircraft. George, David, and his new wife Nilla saw Amelia off from Miami. After completing 22,000 miles of the journey, Earhart and Noonan spent the final layover of their lives in New Guinea. During the next leg to the Howland Islands, radio contact was lost with the airplane, and Earhart and Noonan were never heard from again. A two-week U.S. Navy search over 360,000 square miles found no trace of them. Putnam refused to give up hope, desperately enlisting psychics for assistance, all to no avail. Amelia was declared legally dead in 1939.

A devastated Putnam wrote an homage to his wife entitled “The Sound of Wings.” He remarried in 1939 to his third wife Jean Marie Consigny, but it only lasted five years. He would marry one more time, to Margaret Havilland. Despite his advanced age, Putnam served in World War II in an intelligence unit. Thereafter, he and Margaret operated a resort in Indian Wells, California prior to Putnam’s passing away in 1950 at age 62. His sons, David and George, Jr., led productive lives. David flew B-29’s in World War II and enjoyed a flourishing real estate development career in Fort Pierce before dying at age 79. George, Jr. served in the Navy during the war, and survived the torpedoing of his ship. He owned construction and citrus businesses in Florida, and lived until 2013.

A decade after the engagement of George Putnam to his daughter, Dorothy, Edwin Binney and his family shifted their attentions from North Carolina to Florida, and the creator of Binneywood sold it in 1920. The plantation house burned to the ground thereafter. By Way Farms now operates an equestrian-related facility on the site.

Dorothy would successfully remake her life in Fort Pierce, involving herself in organizations related to women’s rights, aviation, gardening, and conservation. She relished the serenity of her tropical home and orange grove, which she named “Immokolee.” But her marital life was anything but serene. Upton suffered from a serious drinking problem resulting in a rapid end to that union. A third marriage also failed. She finally found contentment in her fourth marriage with Lew Palmer, the orange grove’s manager. She died at age 93 in 1982, but not before sharing with granddaughter, Sally Chapman, the diary of her turbulent but fascinating life. Sally now resides at the cherished Immokolee. She too has a Moore County connection as she is the wife of John Chapman, son of Pinehurst golf great Dick Chapman.

The exceedingly remote possibility that Earhart somehow survived a crash and lived on in the South Pacific is just one of the more recent theories that have kept the lost pilot frozen in time in our minds. Captured in smiling black and white photographs and newsreels, she remains the tousle-haired, rail-slim, modest but fiercely independent heroine who flew over the pine trees into Knollwood Field 86 years ago. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.