By Jim Dodson • Photographs by John Gessner

“I’ve always loved this table,” says Miss Edie Chatham, smoothing her hand over the weathered surface of the large round table that dominates her expansive kitchen in Pinehurst.

“It’s been in our family for a very long time. My daughter brought it all the way from Louisville when Dick and I built this house 30 years ago. She took it apart and drove all that way here, if you can believe it, attached to the roof of her car. Clever girl. The table was fine, a sign of how well it was made. It just gets better with time.”

Now in her 90s — but don’t tell her we told you so — Miss Edie Chatham knows a thing or two about well-made objects and getting better with time.

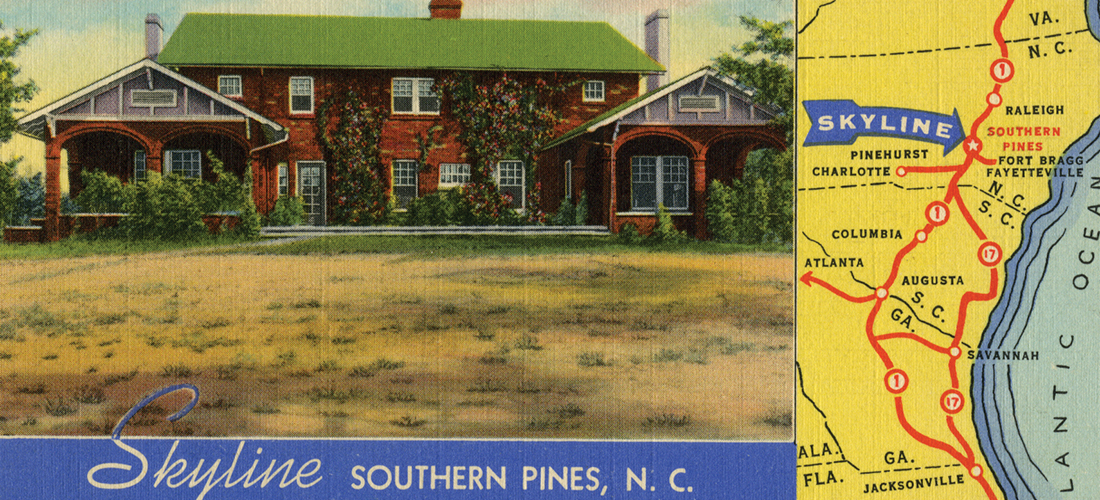

From the beginning, her remarkable life has been one of steady exploration and refinement, beginning with a fearless mother who wished her six children to experience a rapidly changing world to a beautiful house Miss Edie herself sketched out on paper, inspired by 19th century houses from the Carolina low country. The New Jersey architect she and her husband, Dick Chatham, engaged in the early 1980s to draw up the plans for their retirement home, after relocating from Elkins to the Sandhills, had never seen anything quite like the simple two-bedroom “country house” Edie Chatham had in mind. It was modest in scale, in tune with the pragmatism of an earlier age, featuring a simple porte cochère and copper roof that turned elegantly green with the passing seasons, wide and welcoming Dutch front doors equipped with sturdy wooden screens, 12-foot ceilings, and a dramatically wide central hallway running front to back of the house, designed to catch the gentlest breeze and provide a place for Edie’s grandchildren to learn to roller skate and ride bicycles.

“He said it was such a waste of space, but I wanted a house that would stay cool on the hottest summer day,” she explains. “I’d lived in almost every kind of house you can imagine up till then, so I knew exactly what I wanted. We only needed a guest bedroom.”

“Don’t try to talk her out of it,” Dick Chatham advised the architect. “When she gets her mind made up, she never changes it.” The architect obliged though later congratulated her on designing the “perfect dog house” because the windows were large enough for the smallest dog to look out.

A local builder named Clealand Fowler did the work, handcrafting a house that feels as settled and welcoming as any low country home place passed down through generations. “Clealand was terrific,” she remembers. “He built the place a little bit by the seat of his pants, creating as we went along, a real craftsman, making the oversized windows and every door by hand. He did the floors, too. While he worked, I researched.”

It was she who found, for instance, a man in Chapel Hill that had heart pine flooring from Richmond, Virginia’s original railway station when it was demolished to make way for a new station. “The boards were gray and weathered, but Clealand sanded them down and fitted them beautifully together, countersinking the nails and staining them with tung oil. They’ve aged so nicely, don’t you think?”

It was she who found, for instance, a man in Chapel Hill that had heart pine flooring from Richmond, Virginia’s original railway station when it was demolished to make way for a new station. “The boards were gray and weathered, but Clealand sanded them down and fitted them beautifully together, countersinking the nails and staining them with tung oil. They’ve aged so nicely, don’t you think?”

Everything about the house Miss Edie Chatham built seems to have aged nicely, as a matter of fact, from the bathrooms outfitted with old-fashioned fixtures she found at area thrift shops to a sunroom overlooking a backyard woodland where she keeps an eye out for local wildlife, a peaceful sitting room filled with the works of folk artists and American crafts.

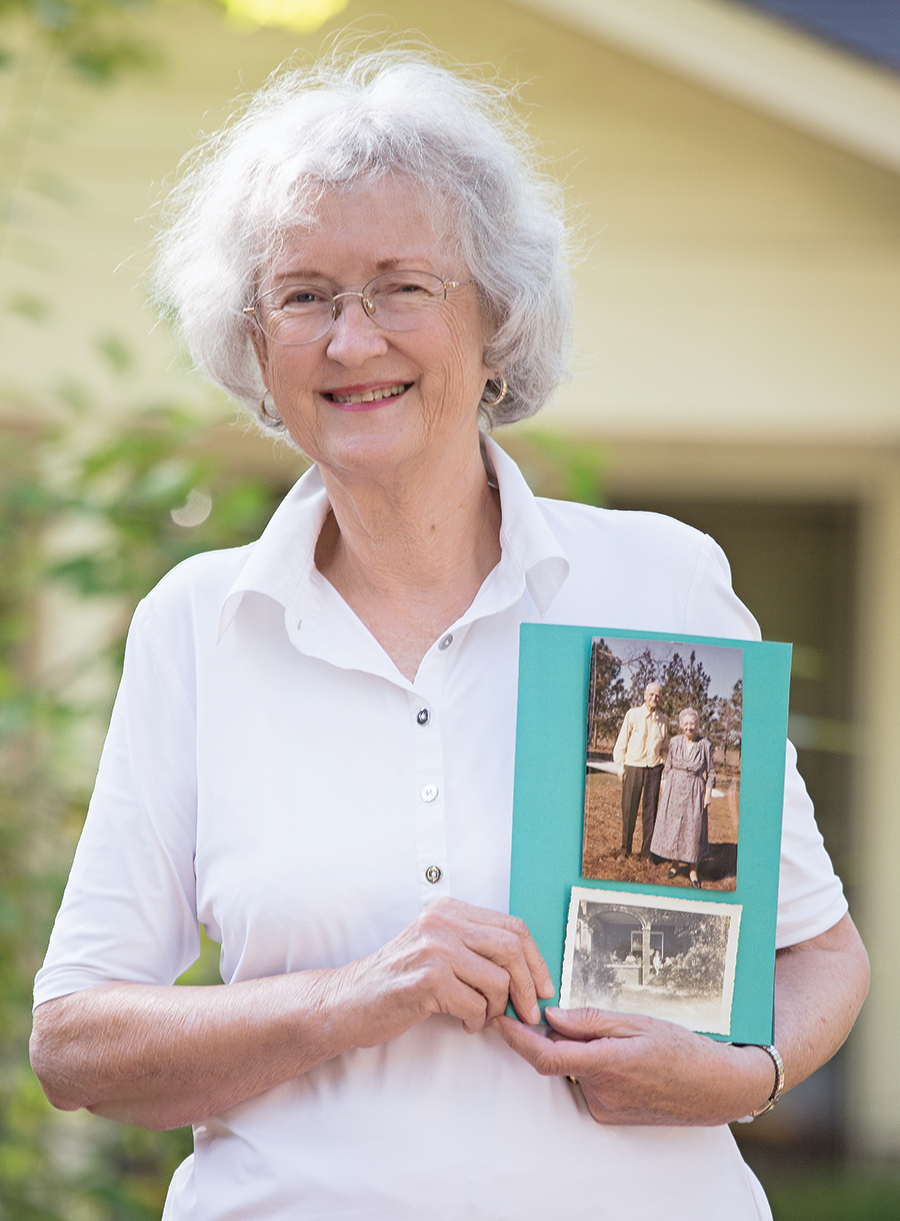

Befitting a family home place, mementos and heirlooms and personal treasures emblematic of the long and notable life Edie Chatham has lived grace every room — favorite books and paintings, family photographs, a refrigerator covered by cards and photographs of her large, loving, scattered clan that includes 11 grandchildren and 13 greats. In 2015, son Richard and his wife, Allison, threw a surprise birthday party for his mother that included a low country boil and four days of paying tribute to their extraordinary matriarch.

“I would have been happy with just a lemon pie,” she allows with a laugh, settling down at the aforementioned pine table to chat — albeit a tad reluctantly — about a life rich in experience and surrounded by family and friends, as mentally vibrant as ever. As she sits, her miniature poodle Susie, 17, appears, curling up at her feet. “But it was so wonderful to have the entire family come from everywhere, some from other countries and very far away.”

She pauses and smiles. “We do seem to be a family that likes to travel a great deal. My brothers and sisters and I all shared that trait — a gift given to us by our parents, who believed the more we saw of the world, the better we would understand others and ourselves.”

She smiles, thinking of something.

“I was just speaking to my older brother Bill last evening on the phone. Bill is 99. His mind’s still so sharp. We were sharing memories of those great summers we had growing up, our travels across America with the Georgia Caravans. Bill was a counselor for the boys on our first trip. That was a very different world back then. I don’t suppose children’s summers are anything like that today. Everyone goes their own way. But, oh, what a grand adventure that was!”

She was Edie Womble then, a precocious 13, the fourth oldest of six children of Bunyon Snipes Womble and his highly independent wife, Edith Willingham Womble, from Macon, Georgia.

Bun Womble, as friends called her father, son of a Methodist minister, was one of Winston-Salem’s most successful lawyers. At age 37, he sat on the board of his alma mater, Duke University, and pushed to integrate the school. He later served in the state legislature and was one of the city’s famous 12 elders who gathered monthly at a private home dressed in formal attire to plan the future of Winston-Salem, planning for the growth of neighborhoods, city government, even the merger of the two neighboring towns. “It was Dad who suggested putting the hyphen between Winston and Salem,” says Miss Edie.

Her mother was also a force to be reckoned with.

“Thanks to our parents, we understood how fortunate we were when so many were suffering due to the Depression. We lived in the same neighborhood as the Hanes and Reynolds families but with six of us all under the age of 8, we all learned to be each other’s best friends very quickly. We made our own beds and straightened our rooms and our father always walked us to school. Our grandmother lived with us, too. It was bliss.”

Edie’s mother had been around the world three times and held strong views about exposing her six children to the realities of life — even, and maybe especially, with the devastation of the Great Depression sweeping over America.

When an enterprising fellow named Clarence Rose came through town promoting a summer-long caravan of buses designed to show children of the affluent South the key sights and landmarks of America, Edith Willingham Womble signed up four of her oldest children for the year 1933, the lowest point of the Depression — Lila, Bill, Olivia and Edie.

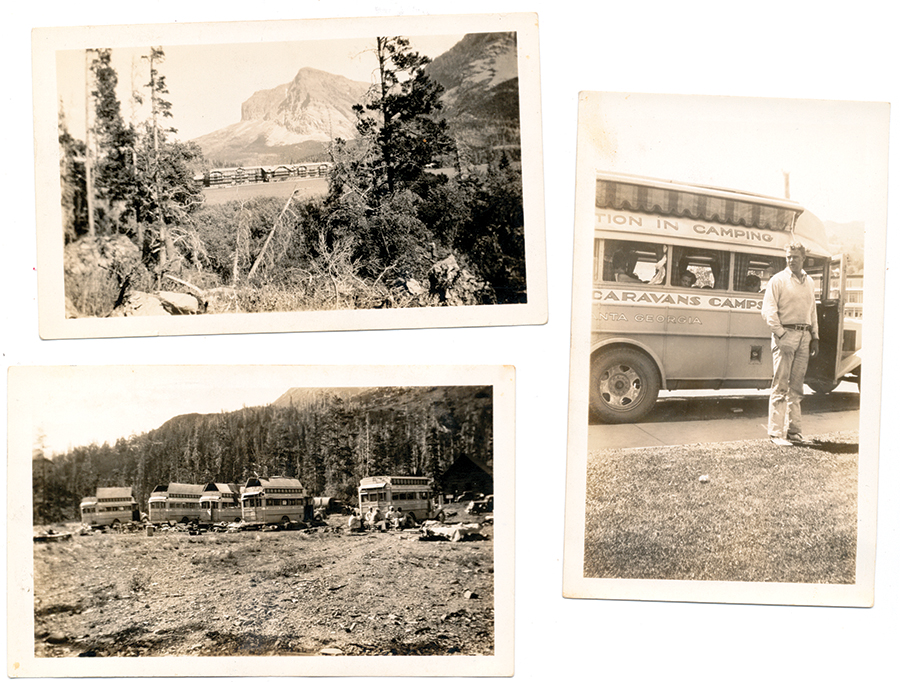

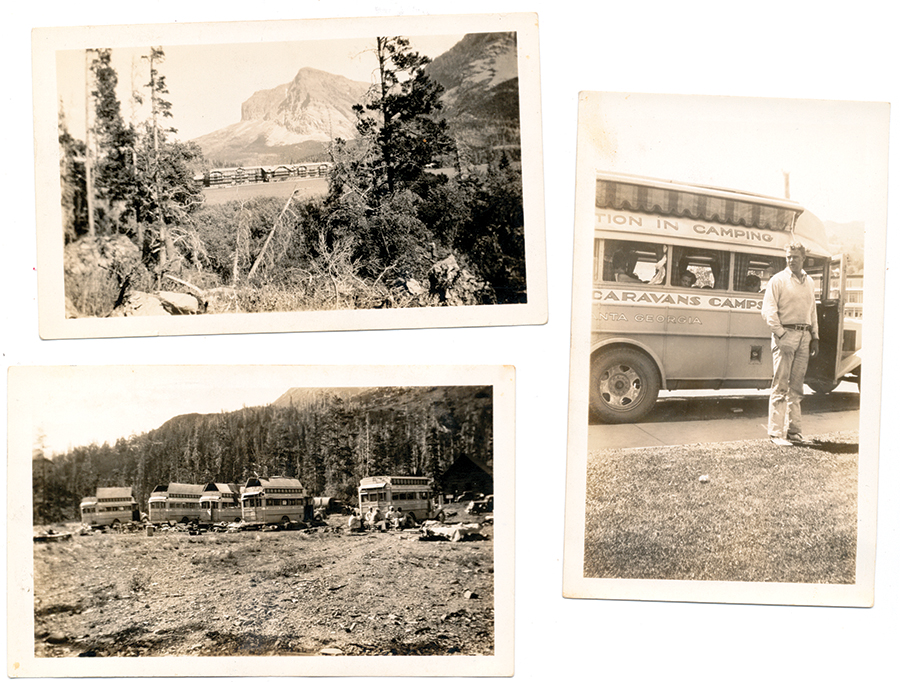

“Dad took us to Atlanta on the train to meet the caravan. There were nine buses that had been customized to carry 16 or 17 children. They were called ‘Spirit of Progress’ buses. The boys and girls were segregated by sex and rode on separate buses based on their ages. Each bus had its own counselor, cook and a full kitchen. Tents and cots came out of the roof to camp, and each camper had his or her own canvas bag with clothing and toiletries and spending money. Dad gave us each spending money to last the entire summer, all the way to the West Coast and back,” Miss Edie remembers.

Three fine automobiles — brand new Lincolns, she recalls — took off before the buses bearing the caravan’s campers. “Rose did things first-class, which is why when he ran short of funds we ate a lot of potato salad later,” Miss Edie explains with a prim smile.

Traveling over rough highways and dirt roads, the caravan’s first major stop was the Chicago World’s Fair of 1933. Celebrating the city’s centennial, the theme of the international exposition was America’s emerging technical innovation. Among the highlights, the German Graf Zeppelin landed and Sally Rand performed for one of the last times. Two other things deeply impressed young Edie Womble. “One was that I got to meet the real Aunt Jemima, the pancake lady. She was very nice to us. Clarence Rose allowed us to wander around the fair in groups of three. I was also struck by models of what highways of the future were going to look like. They looked exactly what interstates do today — four lanes, all paved, overpasses and everything.”

The campers stayed on the grounds of a university in Evanston. If a college or university wasn’t available, the caravan buses camped at local fairgrounds, churches and state parks. “In some towns, people turned out to welcome us. The colleges were the best because most of the roads we were traveling were gravel or dirt roads and we could get showers or baths.”

Onward west they pushed — to the Grand Canyon, Carlsbad Caverns, Yellowstone Park, Los Angeles and Santa Monica, where the children spent a full day riding a roller coaster that went out over the ocean and drank themselves silly on milkshakes. In Los Angeles Edie found a stray kitten she decided to bring home with her to North Carolina. During the return trip, at Yosemite National Park, she witnessed the park’s celebrated 300-foot “Firefall” and met the park’s famous Jaybird Man, who could summon at least 50 different kinds of birds with various whistles. She took photographs with her Brownie camera. She also wrote letters home to her grandmother and the family’s cook, whom she was worried about because her bank back in Winston had folded.

“We honestly didn’t see too many signs of the Depression on the road,” she explains. “The crisis was all still unfolding and we kept moving. We knew it was a difficult time for people less fortunate than we were.”

The cat made it home to Winston-Salem, newly named — what else — “L.A.,” and lived out a nice long life at 200 North Stratford.

The second year she joined Clarence Rose’s caravan, Edie saw Glacier National Park, Banff, Lake Louise and the Calgary Stampede. She brought back a petrified rock from the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona. “There was no air conditioning in the desert, so we wet towels and placed them on our heads. That was our air conditioning,” she remembers.

By then, she notes, Clarence Rose was running out of money and magic. One night he awakened campers in the wee hours and hustled them to the buses in order to outrun local authorities that were demanding he buy special license plates for traveling through their states. A year or so after the Womble children made their final cross-country trip with Georgia Caravan, Rose’s buses were confiscated and sold at auction. The caravan riders had to find their own way home.

“It was a sad end for Rose. We never learned what happened to him. But I think we learned a great deal about being self-sufficient, being unafraid of the world.”

During the summer of 1939, as the shadow of Adolf Hitler crept over western Europe, Edith Womble sent her three middle children on a traditional continental tour of Europe’s cultural capitals. “She knew it might be the last chance to do that before everything dramatically changed — that life would never again be like she remembered it.” Brother Bill had done his European tour in 1935, and older sister Lila actually lived in France for a time.

Edie, a junior at Duke, traveled with her older sister Olivia, a senior, and a group of girls from Duke chaperoned by a campus house mother named Mrs. Pemberton. They landed in Italy, toured ruins and museums before heading for Germany. During a stop in Prague they saw Nazi banners and flags flying everywhere. “And I remembered Bill telling me how when he was there he saw groups of young men in brown uniforms beating up people on the streets. We didn’t see anything like that, though the guide Mrs. Pemberton arranged to give us a tour took us to the Jewish quarter of the city, where we saw many abandoned apartments and empty streets. It was his way of trying to tell us what was really going on in Europe.”

One evening in Munich, a trio of local German boys invited Edie and a couple of friends to a private home to dine. “Mrs, Pemberton let us go because they were very polite and knew English and seemed harmless. The place where they took us was very grand, probably confiscated from wealthy Jewish people we realized later, with a stone courtyard and gate. We had been warned not to ask any questions. After an elegant dinner upstairs, we went down to the basement to play ping-pong and something quite startling happened. Soldiers wearing black uniforms of the SS suddenly appeared, and we were whisked out and held at the front gatehouse while they tried to figure out what to do with us. It turned out that Adolf Hitler and his henchmen had arrived to dine in the club and nobody knew we were downstairs. The Fuhrer was just upstairs! Fortunately, after they debated what to do with us, they decided it was smarter to let us go — telling us to get out of there fast and not look back.”

In Budapest, the servant of a polished young man appeared at their table and invited Edie to dance with his employer on the hotel’s revolving dance floor. He turned out to be the nephew of Hungary’s highest ranked government official, the country’s embattled regent. His name was Denes Marie Siegfried Joseph, Count of Wenckheim, aka. “Count Sigi.” He took her horseback riding in the royal forest and to see his family’s hunting lodge, where his staff fed them a lavish dinner. He also took Edie to see the airplanes of his country’s modest air force. “It was just a few planes but he was very proud of them. I was eager to see them because I’d taken flying lessons at Duke.

“Sigi was charming. He sent me flowers and lovely notes. For several days before we headed for France, we went to dinner and danced. One night, to Mrs.Pemberton’s dismay, we stayed out till dawn. Sigi wanted to show me Budapest by moonlight. Given all that was happening around us, I suppose it was terribly romantic,” she allows. “But it wouldn’t last.”

Over the next year, Sigi wrote Edie Womble several passionate letters and sent photographs until his country fell under Communist control. Eventually, he was captured and shot by a firing squad. In Paris, shortly before heading to England and on to Scotland for the boat home, Edie and Olivia went on a mission for their mother to track down a well-known seamstress their mother first met in Vienna in 1900. The woman was famous for her needlepoint. “She was living in the Jewish section of Paris, and the taxi driver insisted on waiting for us. We knocked on her door, but there was no answer. Some might have given up, but we were taught by our parents never to give up. Eventually a slit in the door opened, and we told the woman who we were. She let us in and it was incredible, the most beautiful fabrics and needlepoint you can imagine. Her name was Mrs. Joli. She’d fled the Nazis from Vienna. The French foolishly thought the war was over. They were taking paintings and other artwork out of hiding. Olivia and I picked out some patterns for our mother’s two tall Italian chairs and paid Mrs. Joli, who promised to send along the coverings as soon as possible.”

Britain declared war on Germany days later, as the Womble girls steamed for America.

“Because of the outbreak of war, mother thought those coverings would never arrive. But amazingly they did — the very next April. Unfortunately, we never heard from Mrs. Joli again. After the war, I went back to Europe and looked for any trace of her, but she and her family were gone. You don’t have to guess what happened to them, poor things.”

Miss Edie Chatham smoothes her hand over her beloved pine table, sighs and smiles.

“Goodness me. Listen to me, how I’m going on.” She touches a small stack of Sigi’s well preserved letters, each baring a Nazi emblem.

“Nothing of the kind,” assures her captivated her visitor.

There is, after all, something deeply rewarding about sitting in such a peaceful house where the afternoon breeze comes through the open kitchen screen door and a woman of the world recalls the most remarkable summers of her life. Softened by her witness to time and surrounded by her sensible old-fashioned house and large loving family, Miss Edie Womble Chatham seems almost ageless. Some women at 70, observed George Bernard Shaw of Queen Cleopatra, seem younger than most women of 17.

Miss Edie graciously offers her guest another glass of iced tea. Eager to sit and hear more, her visitor happily accepts. PS

It was she who found, for instance, a man in Chapel Hill that had heart pine flooring from Richmond, Virginia’s original railway station when it was demolished to make way for a new station. “The boards were gray and weathered, but Clealand sanded them down and fitted them beautifully together, countersinking the nails and staining them with tung oil. They’ve aged so nicely, don’t you think?”

It was she who found, for instance, a man in Chapel Hill that had heart pine flooring from Richmond, Virginia’s original railway station when it was demolished to make way for a new station. “The boards were gray and weathered, but Clealand sanded them down and fitted them beautifully together, countersinking the nails and staining them with tung oil. They’ve aged so nicely, don’t you think?”