This old house returns to its roots

By Jim Moriarty

Sometimes you buy more than a house, you buy a heritage. Early in July, Jennifer Armbrister, her husband, Nicholas Williams, and their 2-year-old son, Mason, moved into Skyline. Armbrister is from everywhere, a self-described Army brat who was in the service herself for nine years. Williams, a Californian, is still active duty, stationed at Fort Bragg, and experienced in places dusty, hot and dangerous.

“We found this place online,” says Armbrister, standing in the kitchen with Mason, who points at a picture of a dinosaur and roars. “There was something about it that drew us to it, both my husband and me. We fell in love with it. There’s this sense of stability and home that I’ve never had before. There’s just something about it.”

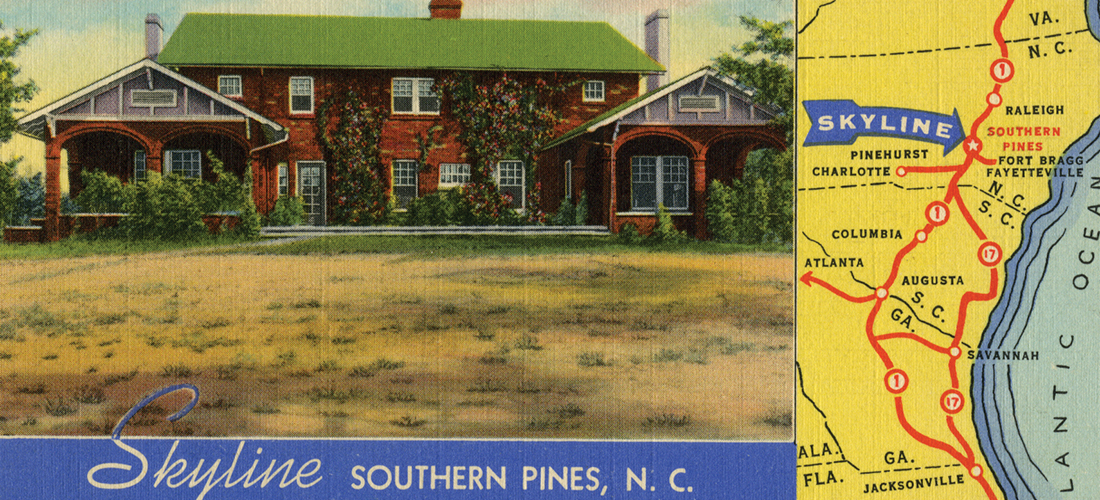

Skyline is a house built very near what is now Hyland Golf Club on a bit of landscape elevated enough and once desolate enough that legend has it you could see Carthage 13 miles away. The nearby highway was Route 50 then, U.S. 1 now. Designed and built by a civil engineer, James Swett, construction of the tapestry brick home began around 1917 and was completed in 1920 for $40,000. A large part of the surrounding 108 acres became a peach orchard, but the unhappy convergence of a peach borer infestation and the stock market crash of 1929 plunged the property into foreclosure.

By December 1930, Skyline was back on its feet, literally. Bearing in mind that Prohibition wasn’t lifted (wink, wink) for another three years, it was turned into a nightclub by John Bloxham and Frank Harrington. A hundred people showed up for the opening, entertained by a seven-piece “orchestra” from Pittsburgh that had been booked for the entire season. Graced by a marquee running the entire length of the roofline and blaring CLUB SKYLINE, by the late ’30s the party was over and Skyline swirled down the drain, back into bankruptcy.

In stepped Arch (at the tender age of 61) and Annieclare Coleman with the financial backing of a cousin, Maj. Gen. Frederick W. Coleman Jr., who purchased the property in ’39 from Citizens Bank & Trust Co. The assessed value of the house, the tenant cottage and the 108 acres was $10,000, though the previous owner was on the hook for 35 large. The Colemans set about turning Skyline into Skyline Manor, one of the many boutique hotels and inns of Moore County.

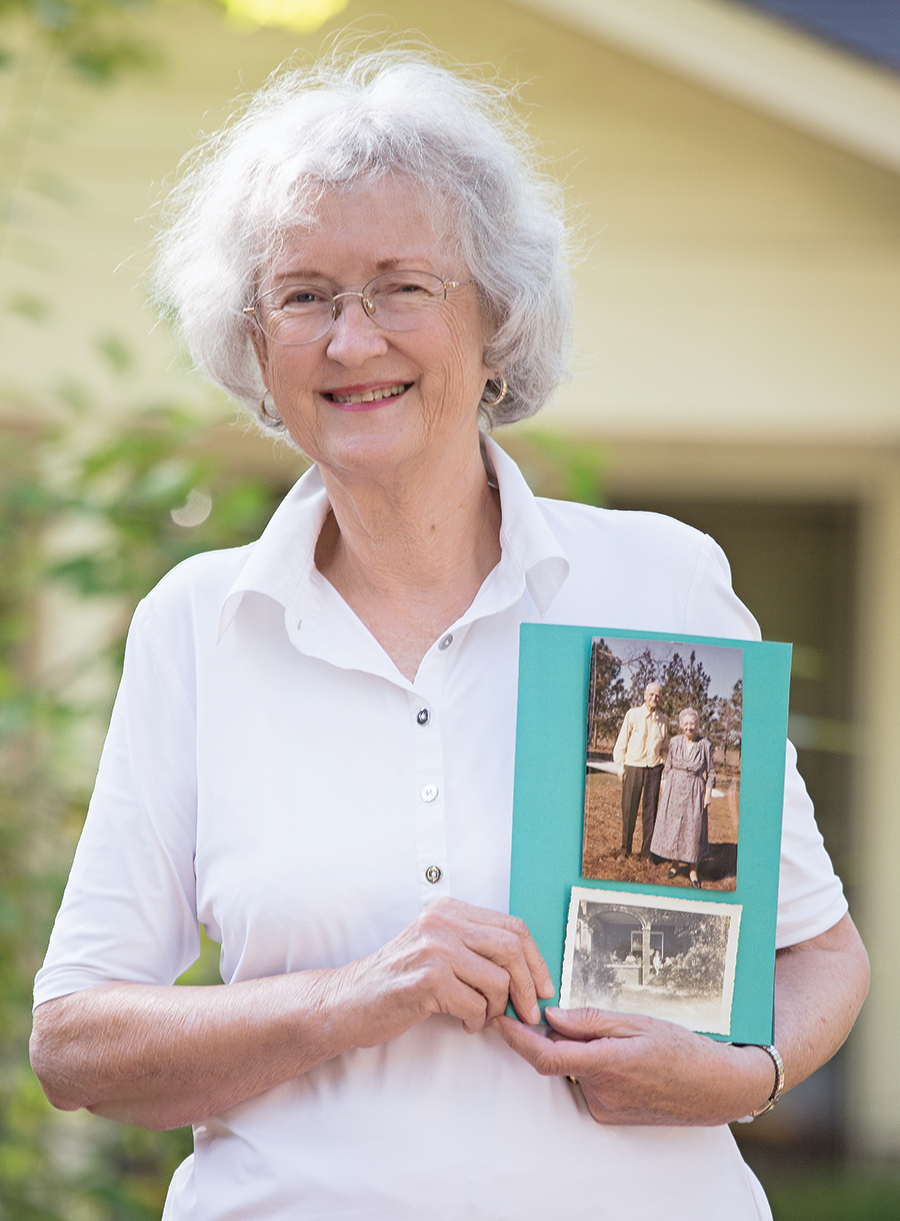

Once the postmaster of Minneapolis — and with a boost from a Minnesota congressman — Arch Coleman had been appointed to the position of assistant postmaster general of the U.S. in the Herbert Hoover administration. A member of Hoover’s Little Cabinet, Coleman is acknowledged in Hoover’s memoirs as a person possessing “future Cabinet timber,” with the former president tossing in Douglas MacArthur and J. Edger Hoover as a couple of other promising up-and-comers. When FDR beat Hoover in ’32, Coleman found himself out of work and in the depths of the Depression. His granddaughter, Deirdre Newton (a Southern Pines resident), says her mother — Arch and Annieclare’s daughter Ruth — described him as “the only politician who ever left Washington without a penny in his pocket.” Post-Hoover, he landed, first, with a brother-in-law in Sanford and then at Skyline.

Coleman was Mr. Outside; Annieclare Mrs. Inside. He cultivated eggplant and was in charge of turning the ‘NO’ on or off in front of ‘VACANCY’ on the neon sign by the highway. She did all the cooking. The house was filled with photographs: Coleman with President Hoover; Coleman with the other under secretaries; Coleman with the congressman from Minnesota. The houseguests had names like Delano and Ives and Rathbun.

“Grandma was a big talker and had a very ambitious nature. Grandpa always listened,” says Deirdre Newton of the man she remembers as tall, thin and reserved. “Then, when he got bored with the whole thing, he’d just stand up, go back into his bedroom, lie on his bed and read detective stories.”

Arch and Annieclare’s daughter, Ruth, lived in England. Her husband, Jack Dundas, was an officer in the Royal Navy. He helped with the evacuation of Dunkirk; captained the HMS Nigeria, escorting cargo ships from America to Mirmansk; was the chief of staff to the commander of the Mediterranean fleet when Montgomery was fighting Rommel in North Africa and, by the end of World War II, the assistant chief of naval staff. The war, however, destroyed his health. In 1946, bound for Skyline, Rear Admiral Dundas, Ruth and their five children came to America on the Queen Elizabeth in its first voyage after being refitted from troop transport to luxury liner.

Also arriving after the war was Arch and Annieclare’s son, Archie. He built a stucco cottage located near the manor house for his wife, Madeline, and their daughter, Claudia, still a Southern Pines resident. Archie had a less visible war record. A member of the Office of Strategic Services — the World War II forerunner of the CIA — he was the second-ranking officer of the Istanbul station of the OSS and in direct communication with William “Wild Bill” Donovan, head of the OSS. Archie was a flamboyant Ian Fleming-style, larger-than-life figure who delighted the Dundas girls, Deirdre and her older sister Rosie in particular, with his guitar playing and singing. “He was a fabulous character,” says Deirdre. “We were in love with Uncle Archie.”

Annieclare passed away in 1960. Skyline Manor quickly ceased to be a business when the real and true manager was gone. By the mid-60s, Uncle Archie had moved to Virginia Beach and Arch Coleman stayed close to his children to the end of his life. The property passed on, too, gradually falling into utter disrepair when the next generation of owners discovered what Coleman had, that Skyline was too big for one elderly man to manage. By the ’80s, upstairs rooms were being rented to Sandhills Community College students, and a hairdressing salon popped up like a mushroom in the basement. The house had become more albatross than heirloom.

“It had fallen into disrepair,” says Frank Staples, who grew up next door. “You could stand in the basement and look clean out to the sky.”

In 1990 it was purchased by Jane and Gary Thomas, who spent the next 26 years bringing it back. “When we bought it, it had been empty for a few years,” says Jane. “We really didn’t know what we were getting ourselves into, but it is a special place.” If Jennifer Armbrister and Nicholas Williams share a military kinship with Skyline, their intention is to revisit its business plan, too, eventually transforming it into a home stay guesthouse. Imagine something a few biscuits shy of a proper bed and breakfast.

Claudia Coleman, the intelligence officer’s daughter, is a well-known local artist who lived in the stucco cottage. “It was a wonderful place to grow up,” she says of Skyline.

It looks like Mason will get the chance to find out for himself. PS

Jim Moriarty is a senior editor at PineStraw and can be reached at jjmpinestraw@gmail.com.