The Perfect Shade

A couple builds their forever home

By Deborah Salomon

Photographs by John Gessner

For Susan and David Wood, their sun-splashed, white-painted brick home in the East Lake section of the Country Club of North Carolina practically glows. White flowers fill the beds. Two spotless white cars repose in the driveway. Inside the front door, walls blind the eye.

One of the hardest things for Susan was finding the right white for the outside brick and inside walls. The one she chose makes Cool Whip look dingy. “White is easier to clean and doesn’t fade,” she says.

But, in fact, white is merely the backdrop for a whole-house collection of blue chinoiserie porcelain and pottery, from tiny figurines and ginger jar lamps to urns big enough to hold an emperor’s remains. Many pieces belonged to parents, grandparents and family members while others were collected through the years. For an accent color, she settled on lime green, and more recently, a pinkish coral reminiscent of Palm Beach lobster and shrimp, from whence came several of her inspirations.

It’s certainly not your typical retirement cottage. David still runs a business and Susan, a graduate of Converse College with a double major in sociology and psychology, still works four days a week in a law office in Rockingham where she’s been employed for many years.

The yellow brick road leading to the Woods’ white brick residence starts in Wadesboro, where Susan grew up in her grandmother’s house, which she describes as “wonderful, gracious Southern living.” David’s childhood was spent in Rockingham where, after obtaining a business degree at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, he returned to work in his father’s business, a chain of five-and-dime stores. Susan and David were introduced by mutual friends and, after a five-year courtship, married. From the start, their homes have been enriched by family heirlooms.

“It’s the kind of house where anybody can just drop in,” says Susan.

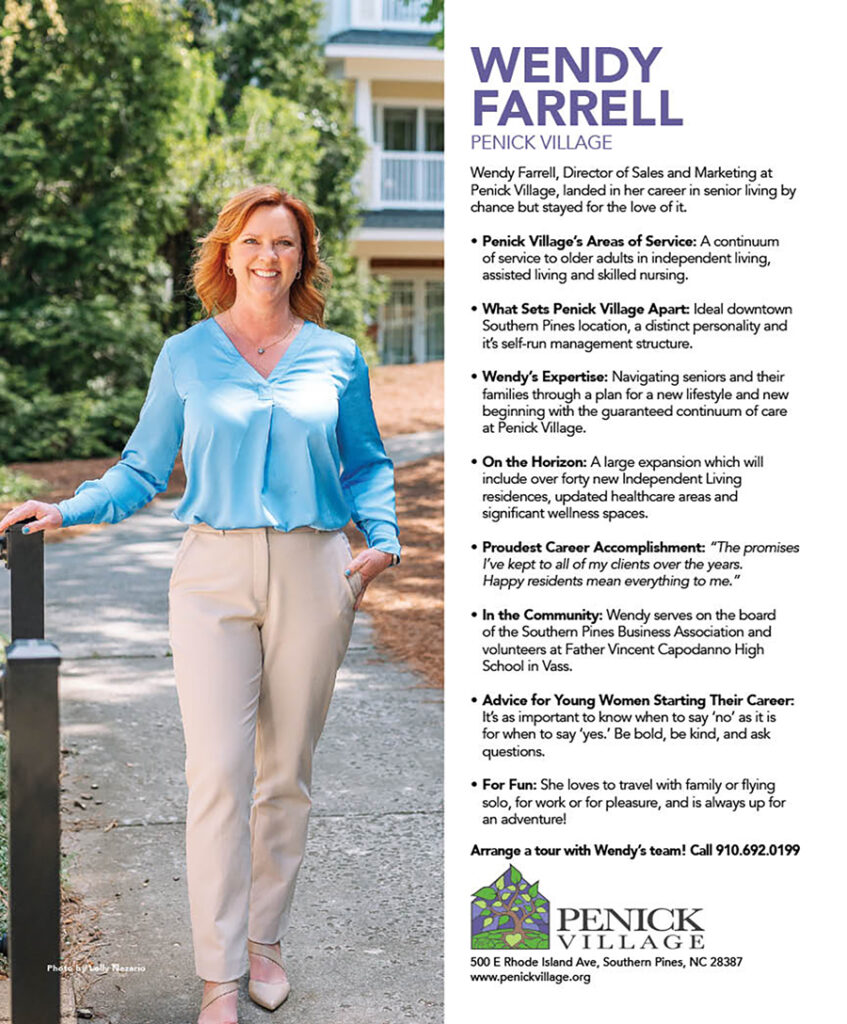

In 2020 Susan’s mother and stepfather moved from Rockingham to Penick Village. Susan and David followed them north. After first scouting in Pinehurst, they decided to build. Susan’s method was to cut and paste photos of houses, details, colors, furnishings to be adapted by builders and interior designers, who appreciated the visuals to flesh out descriptions. The result: personal, striking, gorgeous. And often daring.

The front door, done in panes of beveled glass, opens into an enormous foyer, the kind hardly seen since antebellum plantation house layouts. In its middle is a round glass table on a fanciful base used for overflow dining, since dinner parties can be large, and the dining room, done in lime green-patterned wallpaper, opens conveniently into the foyer. Ten-foot ceilings make rooms feel larger than the actual square footage and provide space for lighting fixtures, some fit for a modern-day Phantom.

The living room introduces bright navy blue accents, repeated throughout the house. An upstairs bedroom elicits gasps for its dark blue wallpaper with circular white figures that suggest movement, while a vibrant green startles guests using the main-floor powder room.

Two glass-and-white gaming tables are positioned on one side of the living room, just inside the veranda with its own fireplace and TV, overlooking the Dogwood Course and pond. “I love playing cards and all kinds of games,” Susan says. Two elephant heads appear as brackets beneath the living room mantel, introducing another icon repeated throughout the house, including a parade of small jade elephants marching across a shelf. The kicker is a glass-topped desk held up by white elephants, a piece tracked down with dogged determination.

A Carolina room, unlike the usual screened porch, is tucked behind the living room, providing space for a mini shrine to David’s alma mater, complete with ram mascot. On the other side of the living room, a TV den has been wallpapered in navy blue grasscloth, dominated by an abstract seascape by Allison McLean.

No surprise: The ground floor master suite features the same colors with a different fanciful wallpaper. His-and-her bathrooms, closets and dressing areas are grouped together, closed off by a door.

The kitchen, a preen-point in most contemporary construction, is notable for its restraint. Moderate in size with a large island, copious storage and combination butler’s pantry and laundry room, its most startling feature is a mirror backsplash over the range.

Susan is obviously a detail person who knows what she wants and how to find it, down to old banister posts shaped like pagodas, which she spotted, had painted white, and fitted onto the posts.

The house took about a year to complete. During construction, the couple rented an apartment in Pinehurst. Now, golf lessons are on their to-do list, along with visits from family.

“We want people to feel at home here, be able to find things easily,” Susan says. To this end, the second floor has several bedrooms, bathrooms, a seating area with coffee-bar/mini-kitchen and a fringed froggy-green love seat sure to spark conversation.

So . . . how do the Woods feel now. David answers in a word: “Happy.” PS

M

M

One chilly

One chilly