Birdwatch

Enticing the Baltimore Oriole

Red carpet treatment for an occasional guest

By Susan Campbell

Northerners who relocate to central North Carolina often ask me about birds familiar to them that seem absent here in our fair state. One that is close to the top of the list is the Baltimore oriole. Its striking plumage and affinity for sweet feeder offerings make it a real favorite among backyard bird lovers.

Male Baltimore orioles are unmistakable with bright orange under parts, a black back and head, as well as two bold white wing bars. Females and immature birds are yellow to light orange with the same white wing bars. They have relatively large, yet pointed, bills, which are very versatile while foraging. Males sing a very melodic song made up of several clear, whistled notes.

As it turns out, Baltimore orioles actually do nest in North Carolina — if you venture far enough west. In our mountains they can be found weaving their elaborate nests that dangle from high branches, often over water. Following two weeks of incubation, the young will spend another two weeks before they fledge. By mid-summer the adults spend their days in the treetops, looking for caterpillars and small insects to feed their growing families.

However, since these birds winter throughout Florida and all the way down into Central America, you might spot a few as they pass through in spring or fall. There is also a chance one or two might spend the winter in your neighborhood if you have the kind of habitat they seek out in the cooler months. Should your yard be to their liking, they may return year after year, bringing others (presumably family members) with them. I know winter oriole hosts in the eastern half of the state who count a dozen or more birds frequenting their feeders October through March every year.

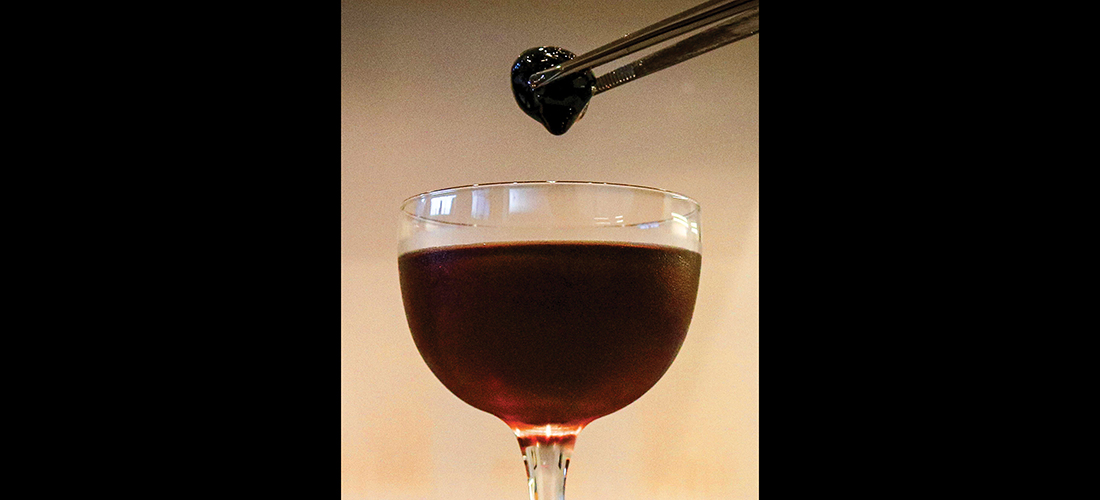

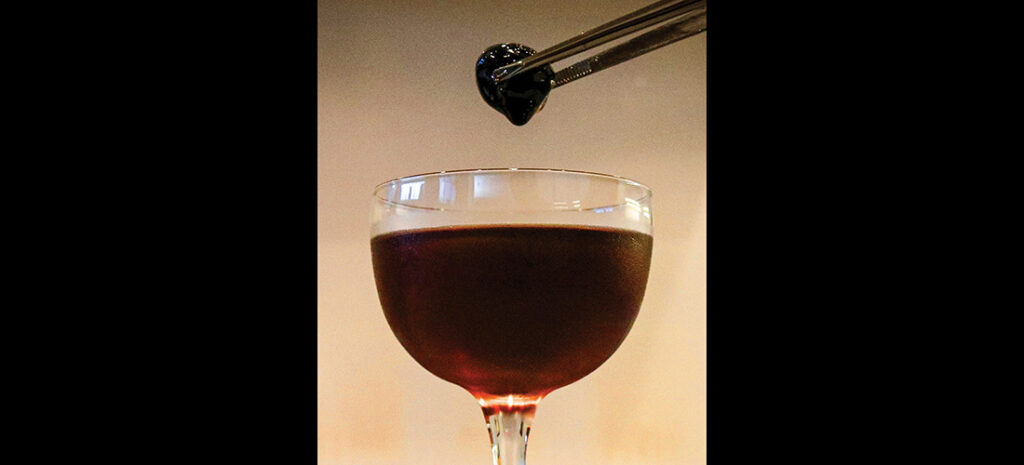

Baltimore orioles will seek out areas with lots of mature evergreen trees and shrubs of which a significant portion bear some sort of fruit. These birds are relatively large and colorful so require thick cover for protection from predators — especially fast-flying bird hawks such as Cooper’s and sharp-shinneds. Without this, it has been my experience that they will not linger long even if food is plentiful. Should they feel safe, the odds are they will settle in and become a regular backyard fixture. Baltimore orioles will continue to consume any insects they happen upon but will switch to a diet of berries and whatever fruit or sweet treats they find at bird feeders. They are known to enjoy not only suet mixes with peanut butter but also orange halves, grape jelly and even marshmallows. They also will avail themselves of sugar water from hummingbird feeders they find still hanging. There are special, large sugar water feeders made for orioles that usually contain partitions for placing other solid treats as well. Baltimore orioles definitely enjoy mealworms, too, should your budget allow.

A few very lucky people have been treated to the out-of-place Scott’s oriole, as well as Bullock’s oriole, here in North Carolina. Interestingly, these mega-rarities have turned up at sites without any other orioles present. Keep in mind that we sometimes find western tanagers at feeders in winter. The females and immature birds of this species look very similar to female or immature Baltimore orioles, differing only in the shape of their bills and the color of their wing bars.

Personally, I have had Baltimore orioles show up for a week or so but then move on. In spite of setting out the red carpet (including suet, jelly, oranges, mealworms and sugar water), they have not been enticed to stay long. Maybe this fall will be a different story . . . PS

Susan Campbell would love to receive your wildlife sightings and photographs at susan@ncaves.com.

Abstract painter Chieko Murasugi has navigated conflicting perspectives all her life. She holds a Ph.D. in visual science and works as an artist; she is the Tokyo-born daughter of Japanese immigrants who was raised in Toronto and lives in America; she is a former impressionist painter who has turned to visual illusion to anchor her geometric art.

Abstract painter Chieko Murasugi has navigated conflicting perspectives all her life. She holds a Ph.D. in visual science and works as an artist; she is the Tokyo-born daughter of Japanese immigrants who was raised in Toronto and lives in America; she is a former impressionist painter who has turned to visual illusion to anchor her geometric art.