Tradition and pageantry on Thanksgiving morn

By Maureen Clark

Photographs by John Gessner and Ted Fitzgerald

On Thanksgiving morning, the Moore County Hounds will invite the public to attend their opening meet, as they have for over 100 years. Hounds, riders, and more than 1,000 spectators will gather around the robed figure of Reverend John Talk in Buchan Field on North May Street for a ritual that dates back to the Middle Ages. Those assembled will hear a blessing of the hounds that launches the formal foxhunting season. The blessing from St. Hubert, the patron saint of hunting, a son of the Duke of Aquitaine who lived in the seventh century, asks that rider, horse and hound be shielded from danger to life and limb.

Established in Southern Pines in 1914, the first hounds hunted from the kennels of novelist James Boyd on his 500-acres, known now as the Weymouth Woods-Sandhills Nature Preserve. In 1929, a separate 2,300-acre parcel was purchased by a small group of foxhunters and, along with the Boyd’s land, it became the nucleus of the foundation later established by W.O. “Pappy” Moss and his wife Virginia “Ginnie” Walthour Moss. The hounds moved to the kennels they now occupy at Mile-A-Way Farm in 1942. Ginnie Moss’s great nieces, Cameron Sadler and Ginny Thomasson, joint master and secretary of the Moore County Hounds, will represent their aunt on Thanksgiving. “I will carry Aunt Ginnie’s whip,” Cameron said. “It’s sentimental and I like to have it with me.”

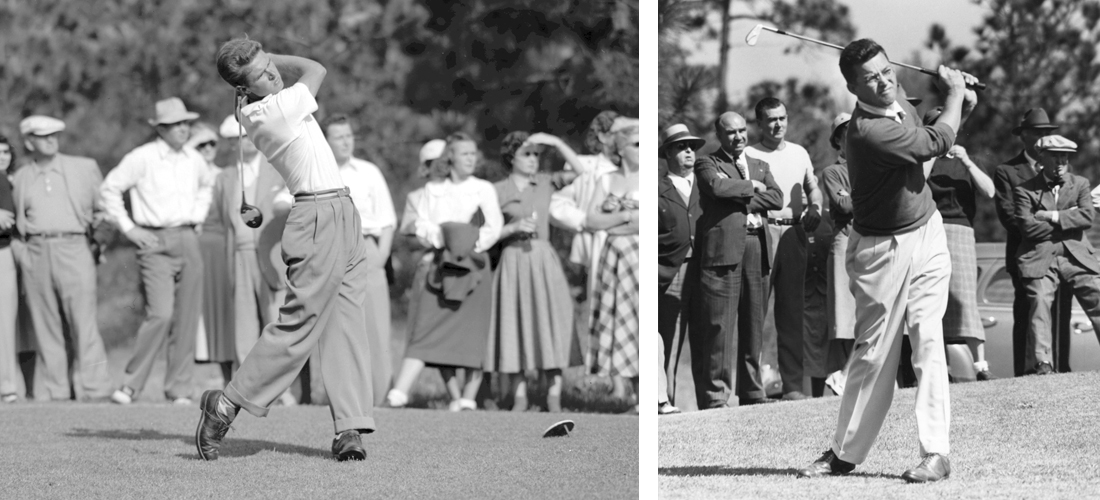

The first to arrive at Buchan Field are the riders, at roughly 10 a.m. on Thanksgiving Day. There is a defined structure to the assembled group. They can be sorted by jacket color. The leadership group of men and women, joint masters and the hunt staff, wear scarlet colored jackets. The rest of the riders make up what is known collectively as the field.

Women and junior riders in the field wear black coats with colors on their collars; navy with red trim for women, red with navy trim for juniors. Men wear scarlet. Colors other than these standards represent riders invited from other hunts. Simple black jackets are worn by foxhunters who have not yet earned their colors.

The Moore County Hounds have five joint masters, Richard Webb, Cameron Sadler, Mike Russell, David Carter, Jock Tate and secretary Ginny Thomasson, who manage the business of the hunt and are leaders in the field at opening meet. Traditional courtesy suggests that all foxhunters greet the masters when arriving at the meet, often lifting a cap.

Horses in the field represent a variety of breeds, from quarter horse to Welsh pony, each matching the rider’s particular size, ability and preference. Cameron Sadler and Russell prefer thoroughbreds, joining many fellow horsemen in giving retired racehorses a new life in the hunt field.

While the crowd is congregating, kennel man Bill Logan, riding a four-wheeler, will drag a prepared scent of animal waste and other matter through the woods. The path, according to Russell, mimics a gray fox with circles, turns and back tracking. Coyote, the usual prey in a live hunt, run faster and straight away. (The evolution in the past 20 years has gone from hunting primarily gray fox to hunting coyote 85 percent of the time.) There will be two checks during the run, breathers for the field to stop, letting horses and hounds catch their breath. The stops, however, will be out of sight of the crowd on Buchan Field.

Soon spectators will see the hounds, tails wagging, coming down the sandy lane from their kennels gathered around their huntsman, Lincoln Sadler. The hounds are never called dogs unless referring to the sex of a male. Sadler manages the pack assisted by five whippers-in, his volunteer staff, working as additional sets of eyes and ears. During the hunt, only the staff is allowed to interact with the hounds.

Cameron Sadler explains that drag scenting for a live pack (one used to chasing coyote or fox) can be challenging. A few will run a drag line but many live hounds, Cameron observed, will not run a made up scent. In their 100-year history, different masters and huntsmen of the Moore County Hounds have hunted various breeds. The current pack, started in 2007, is an American breed called Penn-Marydels. Lincoln Sadler said the pack looks at things like crushed vegetation for tracks. When faced with a different task, the huntsman said they look at him and ask, “What do you want from me?” Last year, at opening meet, Lincoln Sadler tweaked the traditional prepared scent with his own secret concoction and the hounds ran strong. The crowd will be able to judge this year by the strength of the hounds’ voice when they run the line.

Two of the many important tasks of a whipper-in are to help in turning hounds away from roads or off the scent of a second coyote. The whips, working in the field at a distance from the huntsman, give the cry “tally ho” when they “view” a fox or coyote. Tally ho is a blood-chilling yell meant to be heard by all. Two veteran whips with Moore County, Liz Rose and Mel Wyatt, who have won competitions with their yells, will be on hand to call the hounds.

Lincoln Sadler, as huntsman, is the central figure in the hunt with all actions of the masters, staff and field, following his lead. He can be identified by the 9-inch brass hunting horn tucked between the buttons of his jacket. The Moore County Hounds, members of the Masters of Foxhounds of America, are bound by their traditions and rules. All hunts use the 9-inch horn. “It’s the one element that ties it all together,” Sadler explains. “I could hunt another pack and negotiate them through the woods. “

Hounds are not counted as a total number but as couples. Sadler will bring roughly 30 couples this year. The MCH breed two to three litters each year. Litters born in the same season all share the same first letter of their names working through the alphabet like naming hurricanes. This year, all puppies have names that start with the letter Z. On a recent morning at the kennels, Sadler was overheard training puppies he called Zinnia, Zepco, Zesty, Zoloft and Zoe. Two older hounds answered to an age-specific Yaupon and U-Turn. On off days, Sadler works with his puppies, walking them out. Never shouting or raising his voice, a firm command of “hold up together” brings the hounds to Sadler. The walks take them over smells of squirrels and deer, which he teaches them to ignore.

After Reverend Talk bestows the blessing there are several signals the crowd should note. The field of approximately 150 riders will begin dividing into three groups, each behind a joint field master. Cameron Sadler takes the first flight of riders, who can manage the speed and difficulty of jumps following 10 to 12 strides behind the pack. A second flight follows moderately, selecting jumps with good footing. Russell brings the last group, the hill toppers, who prefer not to jump. His distance from the pack, on live hunts, often affords the best views of foxes, coyotes and hound work.

The crowd should also notice when the huntsman, Lincoln Sadler, begins to gather hounds to him. Foxhunting has everything to do with sound, the call of the horn and the voice of the hounds. Sadler gives a very short toot on the horn to bring the hounds to him. People should be moving away from hounds and riders and the huntsman will be “moving off.” In addition to the horn, Sadler whistles, calls and talks to the hounds. The next sound of the horn will be a longer, monotone note saying, “I’m here, keep hunting, keep working.” He will move toward the call of the tally ho.

In the hunt field, some hounds talk a little while they search for scent. Others work quietly. The hounds work together and know when a single hound has hit the scent by the authority and intensity of the initial cry. Sadler said they pay attention when a respected hound named Shrek speaks up. “The hounds honor him,” he explained, going to the lead voice, and joining the cry.

At this point, Lincoln Sadler will blow the horn with an urgency that says to the hounds spread out in the woods or field, “Let’s go, let’s go, let’s get over there and help him. Double up.” When the full pack is on the line and all speaking, or in full cry, it is the cherished sound in foxhunting. Lincoln Sadler will then blow “gone away.” Cameron Sadler praises Penn-Marydels for their strong voice, touching on a needed trait. Alexander Mackay-Smith, the legendary authority on foxhunting, writes that “a good cry in a pack is essential not only for the hunt staff and field, but also so hounds can hear each other and cooperate accordingly.” Hounds that run silent have no value in the hunt field.

When the hounds and riders have gone from Buchan Field into the piney woods, they will be on the Walthour-Moss Foundation. The 4,000-acre tract of long leaf pine, sandy hills divided by fire lanes and streams, is land the Moore County Hounds hunt by cooperative agreement. The crowd should hear the hounds at the end of the drag before they see them spilling over the fence at Buchan Field. The hounds should be followed first by the huntsman, Lincoln Sadler, and his whippers-in. The three fields should follow with the first groups jumping the split-rail fence back to the meet.

The staff, who know the hounds by name, will count heads to be sure all are accounted for with none left behind. The last call blown on the horn and the end of a hunting day is “going home.” Sadler hesitates to blow the strains because they are the same melancholy notes played at the funerals of beloved members of the Moore County Hounds. PS

Maureen Clark is a Southern Pines native who grew up foxhunting.