The Return of the Light

A celebration of food and faith at Pinehurst’s Temple Beth Shalom

By Jim Dodson

One morning not long ago, as shorter days and darker nights began to settle over the Sandhills, we dropped by Pinehurst’s Temple Beth Shalom to visit with the women of Carol Pierce’s cooking class.

In the aftermath of the tragic attack on the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh during which 11 worshippers were murdered as they prayed on a Saturday morning — the worst recorded attack on Jewish people in American history — Beth Shalom’s congregation held a prayer and healing service that filled its sanctuary with people of all faiths from across the Sandhills. On the Sunday before Thanksgiving, the Temple also hosted the 13th annual interfaith service with half a dozen Christian churches from the area. As one member of the Temple family put it, “This was exactly the spiritual lift we needed, an outpouring of fellowship from our neighbors and friends — a way to bring back the light.”

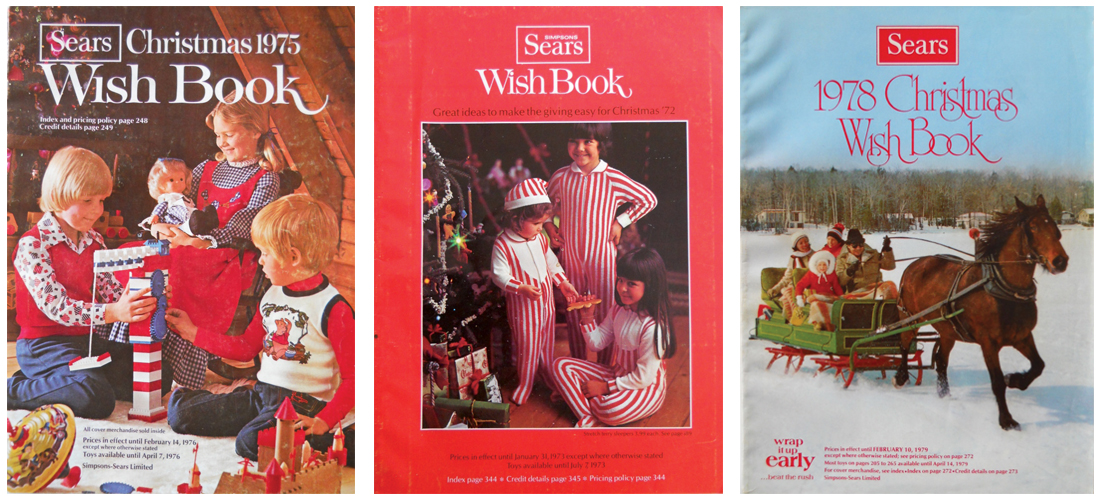

Indeed, with the lights of Christmas shining brightly everywhere these days, we couldn’t think of a better moment to grow that light and celebrate the timeless messages of Hanukkah, the beloved Jewish Festival of Lights that begins on Dec. 2 and ends Dec. 10, a family-centered holiday observed by the sharing of traditional foods, ritual lighting of a special nine-candle menorah and reciting of prayers, playing games and offering gifts over eight nights and days to commemorate the restoration of the Second Jerusalem Temple in 167 BCE.

At that time, the Holy Land was ruled by the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire of Syria that forced the people of Israel to accept Syrian Greek culture and spiritual beliefs in place of their own Hebrew God. Against all odds, a small band of faithful Jews, led by a freedom fighter named Judah the Maccabee, defeated one of the mightiest armies on Earth, drove the Syrian Greeks from their land and reclaimed the Holy Temple in Jerusalem, rededicating it to the divine light of God.

When the victors sought to relight the temple’s menorah in celebration (the seven-branched candelabrum), they found only a single cruse of olive oil that had escaped contamination by the Syrian occupiers. Miraculously, they lit the menorah with a one-day supply of oil that somehow lasted for eight days until new holy oil could be prepared under conditions of ritual purity. To commemorate this miracle, Jewish sages instituted the festival of Hanukkah.

At the heart of the festival is the nightly lighting of a special nine-candle menorah called the Hanukkiah, using the shamash (“attendant”) candle to light one candle each night until all nine candles are ablaze. Special blessings and traditional prayers accompany the lightings, and songs of praise are sung after the candles are lit. Families also exchange “gelt” (everything from jelly beans to coins made of chocolate) and play “dreidel” (a game of chance played with a four-sided top), exchange small gifts and share special holiday foods cooked in oil to symbolize the endurance of the Jewish people. In observant households, lighted menorahs are placed in windows to bring light to the darkness.

“The thing that really brings people together and best symbolizes Hanukkah is the traditional foods,” Carol Pierce explained as her students – Elaine, Nancy, Harriet, Sheila, Bonnie and Audrey — filtered into Beth Shalom’s cozy kitchen area, chatting away about the sudden turn in the weather and their own holiday preparations. “The foods of Hanukkah are fried, symbolic of the miracle of the oil that lit the lamp in the temple.”

“In other words,” someone quipped, “a heart attack on a plate.”

“Hanukkah brings back the best memories,” Elaine Schwartz was moved to say. “Everyone tends to have their own recipes for these foods, but my late mother made the best potato latkes ever. She served them warm from the oven with homemade applesauce and sour cream, and we always played the dreidel game for M&Ms. Unfortunately, she never wrote down her latke recipe and I’ve never quite found one to match it.”

These days, Schwartz added, she observes the holiday by sending her two grandchildren in Colorado gelt-filled dreidels and a nice gift for one of the nights of Hanukkah. “The holiday has changed in some respects. When I was young, my mother would give my sister and me coloring books and crayons for each night and a larger gift on the last night. But kids these days are competing with Christmas, in a way. Hanukkah has been somewhat Americanized,” she reflected. “That’s OK. The holidays share things in common — gifts, food and lights. It’s really about family time.”

Holiday traditions mean everything. As Sheila Rappaport placed her pre-made potato latkes on a cookie sheet to heat up (“You can make them well in advance and freeze them wrapped in paper towels — they keep wonderfully!”), her daughter, Audrey Shalikar, mused how her own children are now in their 30s, but she has kept her Hanukkah decorations at the ready for the expected birth of her first grandchild that is due soon. “So someday when they come to visit,” she says, “I’ll be ready with my mother’s latkes and dreidel games and the full experience of Hanukkah.”

Nancy Jacobs has a lovely story about the ecumenical appeal of a well-made latke. “My late husband, Bob, loved to make latkes,” she remembers. “Every year he spent an entire Saturday making two to three hundred latkes for the open house we always held after the Christmas tree lighting in the village of Pinehurst. Bob sang in the village chorus. He loved both holidays and the people who came to our house — always a hundred or so folks. They loved Bob’s latkes. It was a special evening.”

Over the next full and lively hour, the women of Beth Shalom traded laughs and sweet memories of their own Hanukkahs past as they learned an easy technique from Carol Pierce for making jelly doughnuts, latkes and a special panettone pudding from Fresh Market. There was talk of classic brisket recipes and chicken and matzo ball soup; homemade applesauce and Hanukkah cookies.

At one point Barbara Rothbeind, Beth Shalom’s energetic vice president, stuck her head in to see how the cooking group was faring. “It’s been a difficult year for Jewish people,” she reflected, “but the outpouring from people of faith across this community has been such a blessing. It shows how we stand together in a darkened time — letting our light shine. Hanukkah is all about that —food and family and fellowship.”

As we sampled a second warm and delicious jelly doughnut fresh from the kitchen’s oven, we couldn’t have agreed more.

Fresh Market Panettone Bread Pudding

1 box of Fresh Market Panettone Bread

1 cup heavy cream

1 cup whole milk

2 whole eggs

2 egg yolks

1/4 cup sugar

1 teaspoon grated orange zest

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

Preheat oven to 350 degrees. Cut panettone into 1-inch cubes and place in a 9-by-9-inch greased pan. In a large bowl whisk together remaining ingredients. Pour liquid mixture onto panettone cubes. Press cubes gently until all are saturated. Soak for five minutes. Bake for 60 minutes. Allow bread pudding to cool for 5 minutes before serving. Drizzle with caramel sauce or top with fresh whipped cream.

Easy Potato Latkes

2 cups raw grated potatoes

1/2 cup grated onion

Pinch of baking powder

1 1/2 teaspoons salt

1 tablespoon of flour or matzo meal

2 Eggs

Peel potatoes and soak in cold water for several hours, then grate and drain. Beat eggs well and mix with other ingredients, add a little pepper if desired. Drop spoonfuls on hot greased skillet and cook until golden brown, both sides.

Keep warm in oven until ready to serve with warm applesauce

Easy 10-minute Applesauce

3 Golden Delicious apples, peeled, cored and quartered

3 Fuji apples peeled, cored and quartered

1 cup apple juice

2 tablespoons cognac or brandy (optional)

2 tablespoons butter

3 tablespoons honey

½ 1 teaspoon cinnamon

Combine apples and all other ingredients in microwave-safe container. Microwave uncovered for 10 minutes.

Use blender or potato masher to blend to desired consistency.

Serve warm or chill for later use.

Amazing Brisket

1 4–5 pound first cut brisket

1 cup dark brown sugar, lightly packed

1 package Lipton Onion Soup Mix

1 bottle Heinz Chili Sauce

Potatoes and carrots

Heat oven to 350 degrees

Place brisket in deep roasting pan. Combine sugar, soup mix and chili sauce; spoon over meat and cover pan. Cook for 2 1/2 hours, remove and cool for one hour.

Slice meat against grain, cover and cook brisket for another 2 hours, or until brisket is tender.

Add quartered red bliss or Yukon Gold potatoes (unpeeled) plus a small bag of baby carrots and cover with sauce, for the last hour.

Kugel

12 ounces noodles

1 cup cottage cheese

1 cup sour cream

3 eggs, beaten

1 stick butter, softened

Salt and pepper to taste.

Cook and drain noodles according to package directions. While still hot, add the other ingredients and stir well. Pour mixture in greased casserole and bake in preheated 350-degree oven 35 to 40 minutes.

For variety (and to make it sweet), you can add 1/2 cup sugar, 1/4 teaspoon cinnamon and a handful of raisins,

To make it savory, add only 1/2 stick of butter. Then sautée one medium chopped onion, 1/2 cup chopped mushrooms and 1/4 cup chopped celery When veggies are browned, add to noodle mixture and bake as above.

Pour mixture in greased casserole and bake in preheated 350-degree oven 35 to 40 minutes.

Can be frozen — defrost completely before warming in a 350-degree oven 10 minutes.

Matzo Balls

1 cup water

1 stick butter

1 cup matzo meal

Parsley, sugar, salt, paprika, ginger, nutmeg and grated onions to taste

3 eggs, separated

In a medium sauce pan combine water and butter. Heat until butter dissolves. Add matzo meal and stir until water is absorbed. Season to taste with parsley, sugar, salt, paprika, ginger, nutmeg and grated onions. Mix well.

Beat egg yolks until lemony and add to matzo mixture. In a clean bowl, with clean beater, beat egg whites until stiff; fold into matzo mixture. Chill well in covered container for at least 4 hours

To make the matzo balls, dip fingers in warm water and roll chilled mixture into balls.

If you wish to freeze, place on a cookie sheet and freeze. The frozen balls can be placed in a plastic bag until you need them. When ready to use them, drop them in boiling chicken broth and cook for 30 minutes on medium heat.

Add to your favorite soup! Yield: 27 medium/small matzo balls

Simple Chicken Soup

3 chicken breasts

4 carrots, halved

4 stalks celery, halved

1 large onion, halved

Water to cover

Salt and pepper to taste

1 teaspoon chicken bouillon granules (optional)

Put the chicken, carrots, celery and onion in a large stock pot and cover with cold water. Heat and simmer, uncovered, until the chicken meat falls off of the bones (skim off foam every so often).

Take everything out of the pot. Strain the broth. Pick the meat off the bones and chop the carrots, celery and onion. Season the broth with salt, pepper and chicken bouillon to taste, if desired. Return the chicken, carrots, celery and onion to the pot, stir together, and serve.

Mandelbrot

(A sweet bread similar to biscotti)

3 eggs

1 cup sugar

1/3 cup vegetable oil

1 teaspoon vanilla

2 3/4 cups flour

2 teaspoons baking powder

1/2 teaspoon cinnamon

1/4 teaspoon salt

1/2 cup walnuts

Optional: chocolate chips, dried cranberries.

Beat the eggs and sugar until light and fluffy. Add the oil and vanilla and mix thoroughly.

Sift the flour, baking powder, salt and cinnamon together and add to the sugar mixture. Mix until blended, adding the nuts as the dough starts to come together.

Briefly knead the dough on a floured surface. Divide into 2 pieces and shape each into a log about 3 inches wide. (Add chocolate or cranberries at this point.)

Place logs on greased cookie sheet. Bake at 350 degrees for 30–35 minutes, until golden.

Remove from oven and let stand until cool enough to handle. Slice logs diagonally into 1/2-inch slices. Lay them on the cookie sheet cut side up and return to oven.

Bake on the top shelf for 10 minutes and then on the bottom shelf for 10 minutes until toasted and brown.

Sweet Sufganiyot

(Traditional jelly doughnuts)

3 cups flour

2 teaspooons baking powder

2 tablespoons sugar

1/2 teaspoon vanilla

1/2 teaspoon nutmeg (optional)

2 eggs

2 cups sour cream

Oil for frying

Jelly (any preferred flavor — black raspberry a favorite)

Powdered sugar

In a bowl, blend together the flour, baking soda, sugar, vanilla, nutmeg, eggs and sour cream.

In a skillet, heat the oil, and when very hot, drop tablespoons of batter into it. When the batter puffs up and turns light brown, turn it over and cook the other side.

Set doughnuts on paper towel to cool.

Make a small hole and fill with jelly. A cooking syringe can make this easy. Sprinkle with powdered sugar and serve immediately. PS