How a unique hobby helped restore a historic course

By Bill Case

In 2009, Bob Dedman Jr. and Don Padgett II, the gentlemen in charge at the Pinehurst resort, decided to dramatically overhaul Pinehurst course No. 2, one of America’s foremost championship golf venues. They sensed that the layout, built by Donald Ross in 1907 and periodically tweaked thereafter by the legendary architect until his death in 1948, had lost some of its character.

Starting around the early 1970s, Pinehurst had adopted the popular course maintenance formula of the era: lush green grass throughout the course, not just in the fairways. The native pine barren wire grasses and awkward sandy lies that confronted off-target golfers on No. 2 during Ross’ heyday largely disappeared. In their place came acres of 3-inch-deep irrigated grass. Too often, extrication from this cabbage could only be accomplished by hacking a wedge back to the fairway.

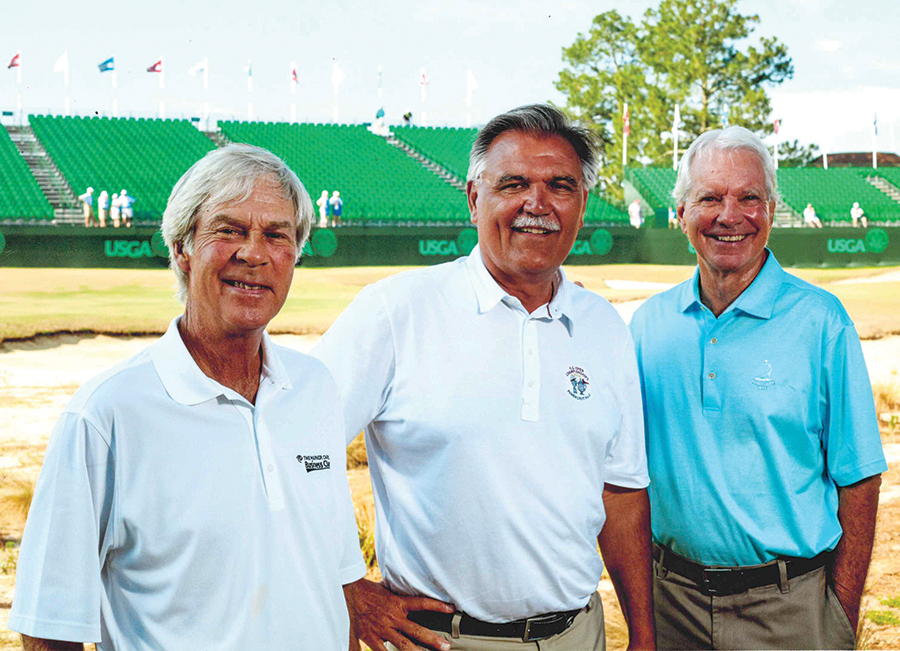

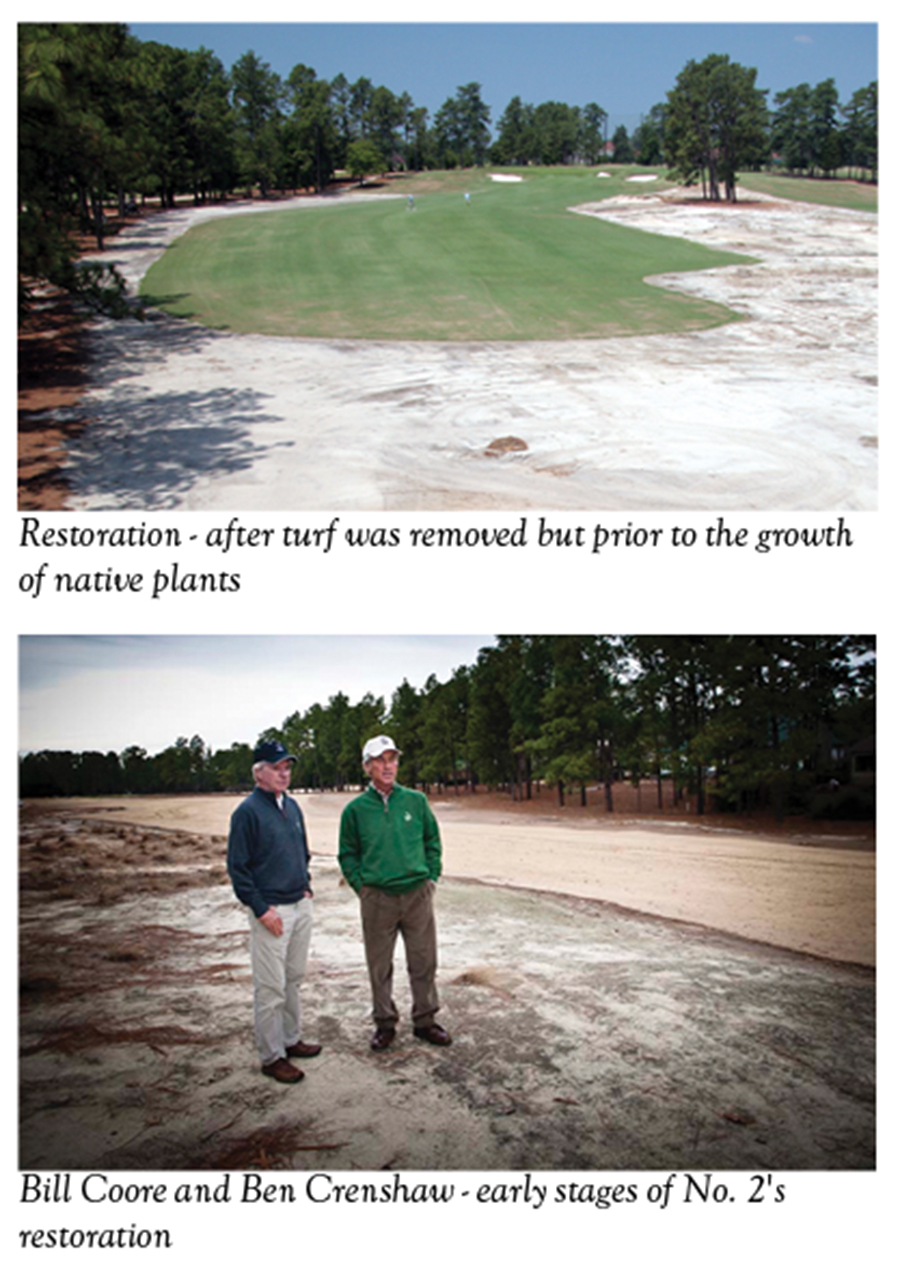

To restore No. 2 in a manner that approximated how Ross had presented the course, Dedman and Padgett called upon esteemed course designers Bill Coore and two-time Masters champion Ben Crenshaw. The Coore & Crenshaw website describes its design philosophy as a blending of Bill’s and Ben’s “personal experience and admiration for the classical courses of Ross, MacKenzie, Macdonald, Maxwell, and Tillinghast to create a style uniquely their own.”

The architects have a special connection to Pinehurst. Having already won in his professional debut, a 21-year-old Crenshaw nearly captured his second event as a pro, too, finishing second in the 1973 World Open, three strokes behind Miller Barber. The 144-hole marathon on No. 2 “stimulated my love for Pinehurst,” says Crenshaw. Coore, who grew up in Davidson County, North Carolina, was good enough to make Wake Forest University’s golf team and played No. 2 frequently in the 1960s, usually on $5 all-day passes. “There is no doubt,” he says, “that playing No. 2 gave me an appreciation of traditional, strategic golf courses that eventually pointed me in the direction of course architecture.”

While Coore & Crenshaw’s selection was applauded in golf circles, more than a few aficionados wondered about the potential impact of a drastic change. Why make major modifications to a course that only recently had held one of golf’s most dramatic major championships, the 1999 U.S. Open? What was the benefit of eliminating rough in favor of native waste areas? Didn’t the United States Golf Association prefer deep rough and narrow fairways? Could changing the character of No. 2 jeopardize its status as a championship venue?

Though they didn’t say so publicly at the time, Coore and Crenshaw also harbored misgivings. Coore knew that No. 2’s fairways had once stretched to nearly 50 yards in width. Now they averaged just 24 yards across. If the more generous dimensions were restored, would the USGA find fault or, worse yet, require the fairways be narrowed again for the 2014 men’s and women’s U.S. Opens?

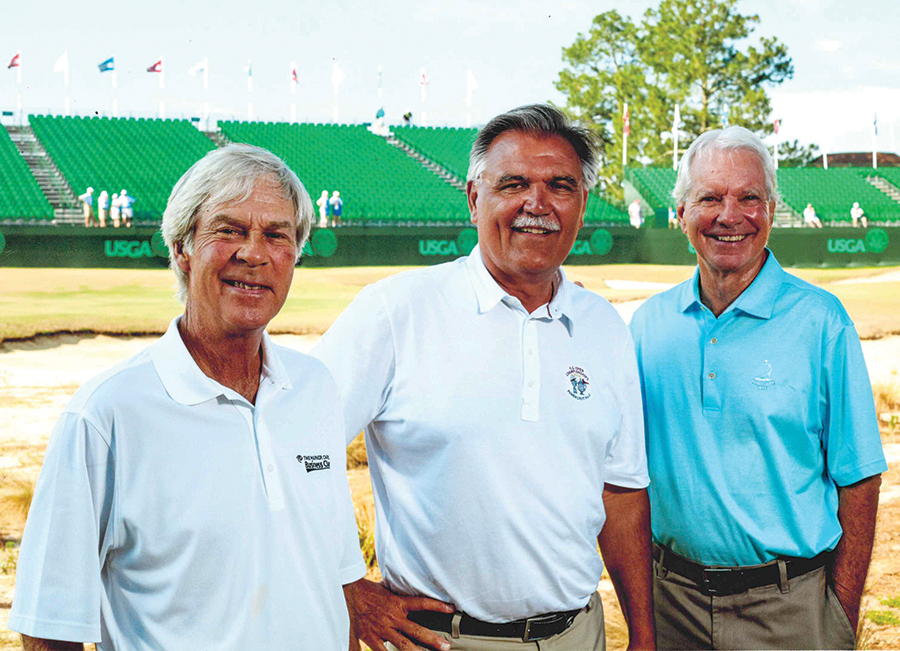

The two architects had no interest in undertaking No. 2’s restoration if it might do more harm than good. Mike Davis, who had been in charge of setting up U.S. Open courses for years and who would become executive director of the USGA in 2011, promised that modifications resulting from the restoration would not be undone by the USGA. Indeed, Davis himself had broached the concept of restoring No. 2 in discussions with Dedman and Padgett.

But there remained a gnawing concern for Coore and Crenshaw — they wanted to know the precise details, dimensions and appearance of the course during the Ross era.

Bob Farren, the man in charge of maintaining the resort’s courses, provided an invaluable first clue. He advised that during the 1980s, his crew had uncovered the entirety of the abandoned fairway irrigation line that Ross had installed in 1932. Farren flagged the path of the defunct line for the architects. Its location confirmed that No. 2’s fairways had previously been configured in a more serpentine fashion. Due to mowing patterns, the fairways gradually became straighter in the 80 years following Ross’ placement of the irrigation line. Farren’s discovery enabled the architects to replot the location and dimensions of No. 2’s fairways to match the old Ross footprint.

But puzzles remained. What did the old native areas look like? Had the location and shape of greens, tees and bunkers changed any over the years? How did Ross sculpt the bunkers? To find answers, Coore and Crenshaw paid a visit to Pinehurst’s Tufts Archives and combed its remarkable collection of historic photos. Their research proved useful in providing an overview of the course’s general appearance, but photos illustrating hole-by-hole details were few. And those that did exist were snapped at ground level. Bill and Ben had hoped to find aerial photos that might provide a clearer, to scale, perspective of No. 2’s architectural details.

Though intimately familiar with Ross’ design style, absent more detailed photos, they were going to have to engage in a significant amount of guesswork. How could they be sure they were accurately restoring the course to the way Ross had left it or, at least, how he would be inclined to draw it up today? “Lord knows,” reflected Coore later, “we didn’t want to be known as the people who messed up No. 2.”

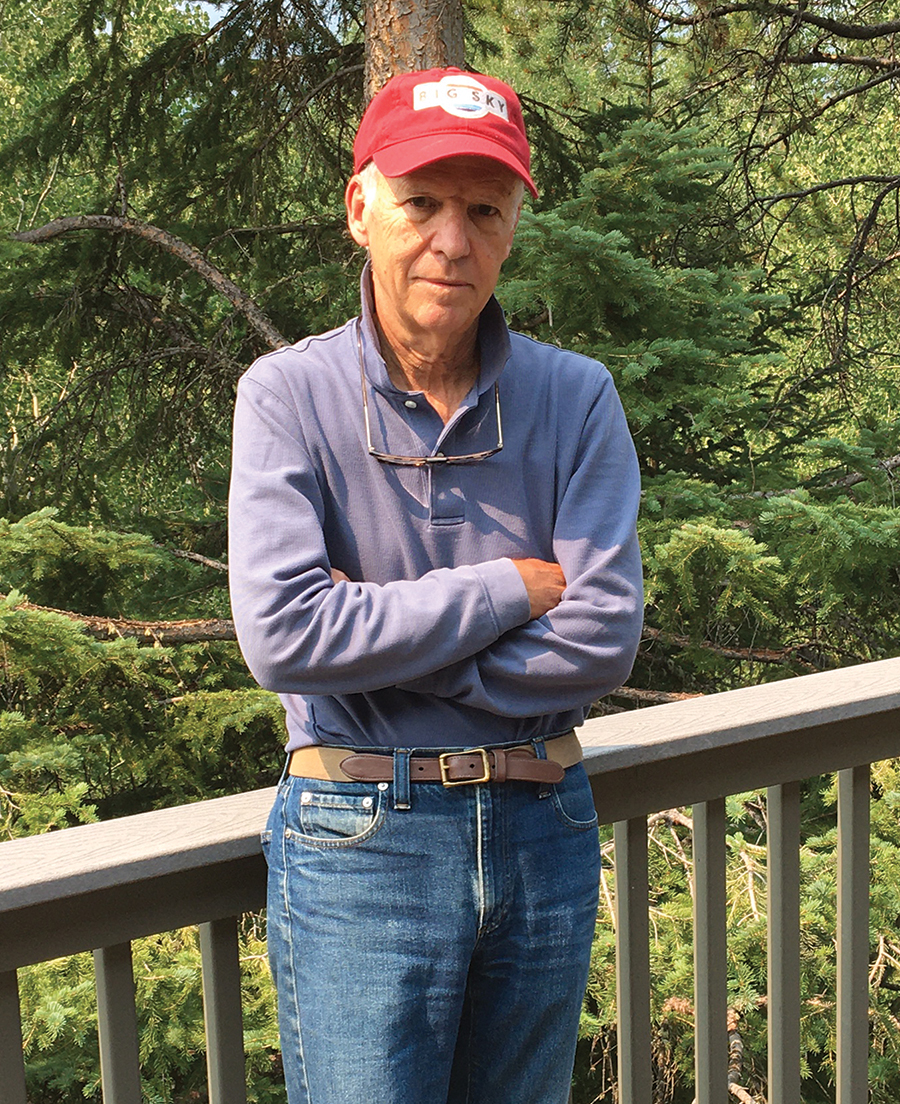

Unbeknownst to the architects, help would soon be coming their way, in the form of Craig Disher, a 65-year-old Washington, D.C., resident who was a decade into retirement after a 31-year career with the National Security Agency. Disher was an enthusiastic golfer, typically scoring in the low 80s at Manor Country Club in nearby Rockville, Maryland. His zest for the game ultimately steered him toward an avocation of his own creation.

It happened in 2004 after Disher read Lost Links, by Daniel Wexler. According to the book, various federal agencies had photographed vast portions of America from the air, and the millions of aerial images housed at Washington’s National Archives and Records Administration included many of golf courses. The United States Geological Service, the most prolific shutterbug among the agencies, had begun the process of photographing the country in the 1930s. There were various reasons for the program, one of which was inventorying America’s arable land. Even though crops aren’t customarily grown on recreational properties like golf courses, the USGS shot them anyway in the event the land might have to be used for food production or other necessities. This had actually taken place during World War II when “Victory Gardens” were patriotically planted on the nation’s courses, and cows grazed on the formerly pristine fairways of Augusta National Golf Club.

Disher thought it would make for an enjoyable project to search for aerial pics of his home course, Manor CC, designed in 1922 by noted golf architect William Flynn. Besides, the place where the USGS images were stored, NARA, was just a 15-minute drive from Disher’s home. After being directed to the cartography and map research room on the third floor, he got a crash course on the ins and outs of researching and retrieving aerial images from NARA’s vast catalog.

Finding images taken in the USGS project wasn’t a particularly difficult task. Rolls of large 9×9 negatives kept in stored cans were indexed by state, county and date. After identifying the rolls pertaining to a particular county, a researcher would request them, then generally wait a day or two before they were made available. Once the rolls were in hand, the researcher could sift through them on a light table, hunting for particular negatives.

The project was right up Disher’s alley. He enjoyed research and the patience, concentration, and persistence it required. A history major at Gettysburg College, his senior thesis (the evolution of Mao Zedong’s communist philosophy and politics) had necessitated innumerable hours wading through hundreds of magazines, newspapers and other documents at the Library of Congress.

“Organizing and cross-referencing them in the era before computers was great training,” Disher says. “My research at NARA mirrored that experience.”

His resourcefulness was augmented by life experiences. After college, during a stint in the U. S. Army, Disher received training in military interrogation at intelligence school and served as an interrogator during the Vietnam War. A significant portion of his employment at NSA had involved the deciphering of encrypted messages. As Disher puts it, that work, in contrast to library research, “primarily takes place in one’s head.”

From NARA’s index, Disher found that rolls of negatives taken in Montgomery County, Maryland (Manor CC’s location), were available. He found aerial images of Manor taken during the years 1940, 1948 and 1951. He photographed the negatives, then used Photoshop on a computer at home. This resulted in sharp black-and-white photographs that depicted the Manor course in riveting detail.

Delighted with the success of his search, Disher soon became a regular at the cartography and map research room, looking for and collecting aerial images of other golf courses in the Washington, D.C., area. It wasn’t long before his quest extended to courses that interested him around the United States. His most frustrating search involved the Lido Golf Club on Long Island, closed permanently due to wartime needs in 1942. Classic golf architecture devotees reverentially extoll this mystical links, ranking it among the finest ever built in the country. Locating aerial photos of Lido became something of a white whale for Disher, especially after he discovered USGS had not taken any photos in the area.

Undeterred, Disher considered whether the Department of Defense might have photographed Lido. Before and during World War II, DOD had arranged for military installations and areas of strategic importance to be photographed from the air. NARA had materials relating to these aerial flights, but researching them could be vexing due to a lack of indexing. However, NARA did hold records showing the flight patterns of planes that had flown on aerial photography assignments. The paths were depicted by the drawing of black lines of the planes’ tracks on acetate sheets. By superimposing those sheets over a geological map, a researcher could determine the general area where photography had taken place.

The information on the acetate sheets had been converted to microfilm. To search for Lido, Disher “had to look at all the microfilm rolls showing tracks of aerial photography planes in Long Island prior to 1942. Each roll of microfilm had to be viewed from start to finish, stopping at each track image to see if it passed over the area of interest.” Once those track images and the associated roll of negatives were identified, Disher would order the can containing them. The wait for the cans took additional time, since DOD images were in cold storage outside of D.C.

“It took me a month, but I finally found an undiscovered 1940 aerial photo of Lido,” he says. Disher shared the image with golf historians, and the highly detailed photograph subsequently appeared in several golf magazine articles, spurring an ongoing movement to someday recreate Lido’s majestic course.

Slowly, people in golf became aware of Disher’s research. Given the architectural trend of restoring classic courses to their original design, old photos — especially aerials — were in high demand. Without any thought of benefitting financially from his unique hobby, Disher cheerfully shared access to his collection gratis with grateful golf clubs and course architects who asked for his help. Disher furnished them 16×20 prints of aerial photos that were used in field work. Later the same prints often found their way to clubhouse walls.

In 2005, the avid golfer and his wife, Susan, acquired a vacation home in Pinehurst. This development, naturally, caused Disher to scope the USGS collection at NARA for images of No. 2. When he got wind of the fact that the Pinehurst resort intended to restore No. 2 to its original Donald Ross design, he thought the USGS photos might be of value to the architects. When he retrieved the images, Craig found to his frustration they lacked sufficient detail to be of much use. He wondered whether there was a possibility DOD might have also photographed the course. Pinehurst was only 26 miles from Fort Bragg, a base Disher knew well. During his ’60s hitch in the Army, his basic training had been at Bragg. Disher knew area flights involving aerial military photography likely would have departed from nearby Pope Air Force Base. He knew Pope, too. In 1968, he was deployed from there to Vietnam, where he had joined a brigade of the 82nd Airborne Division.

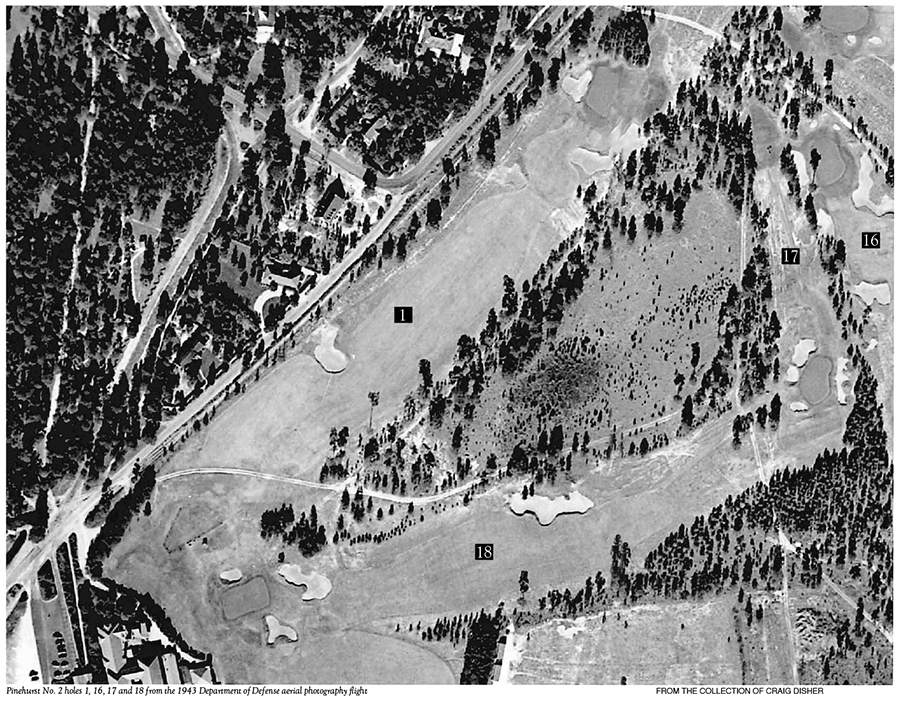

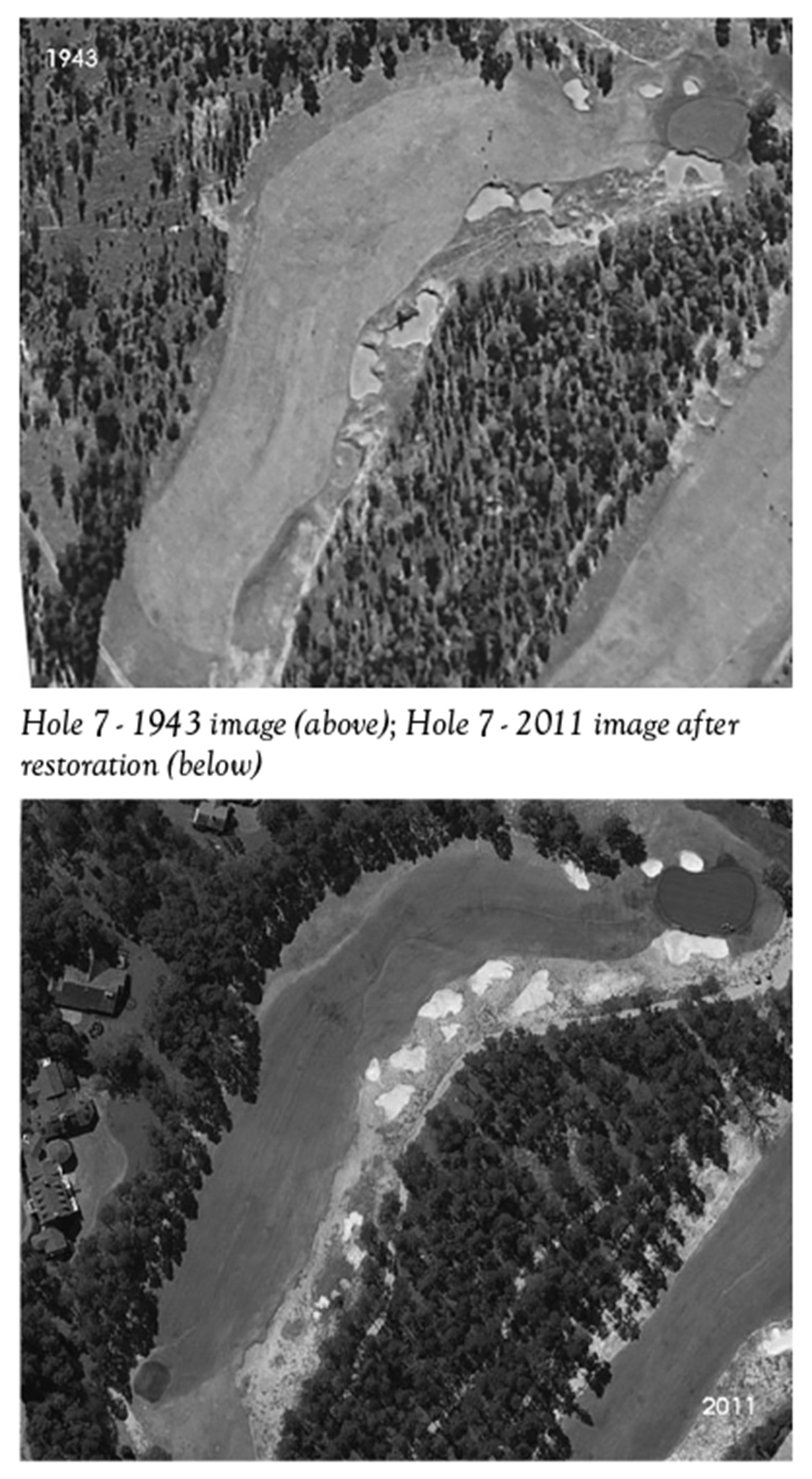

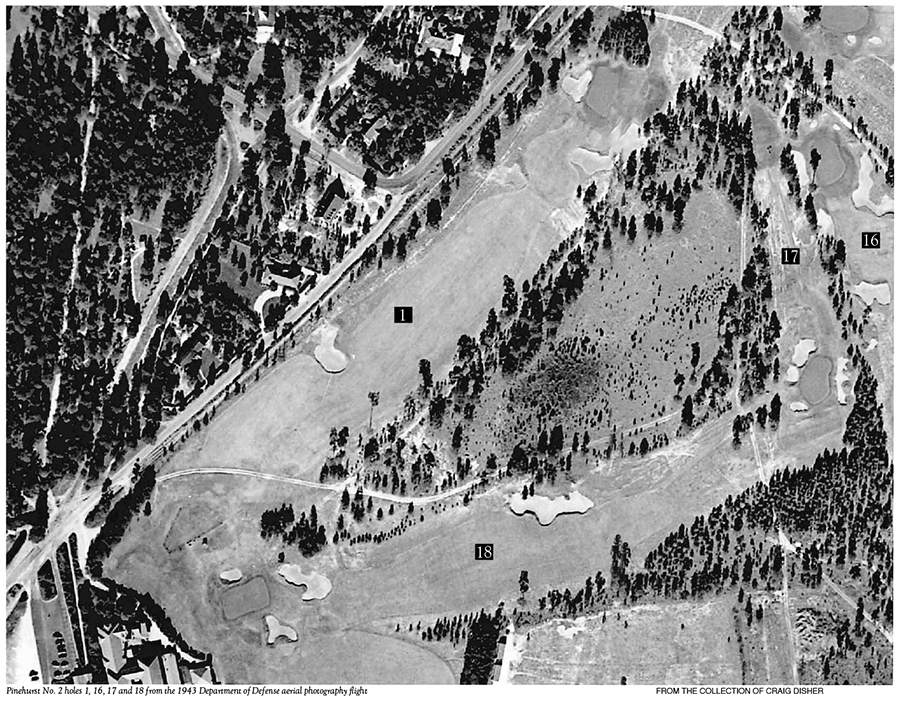

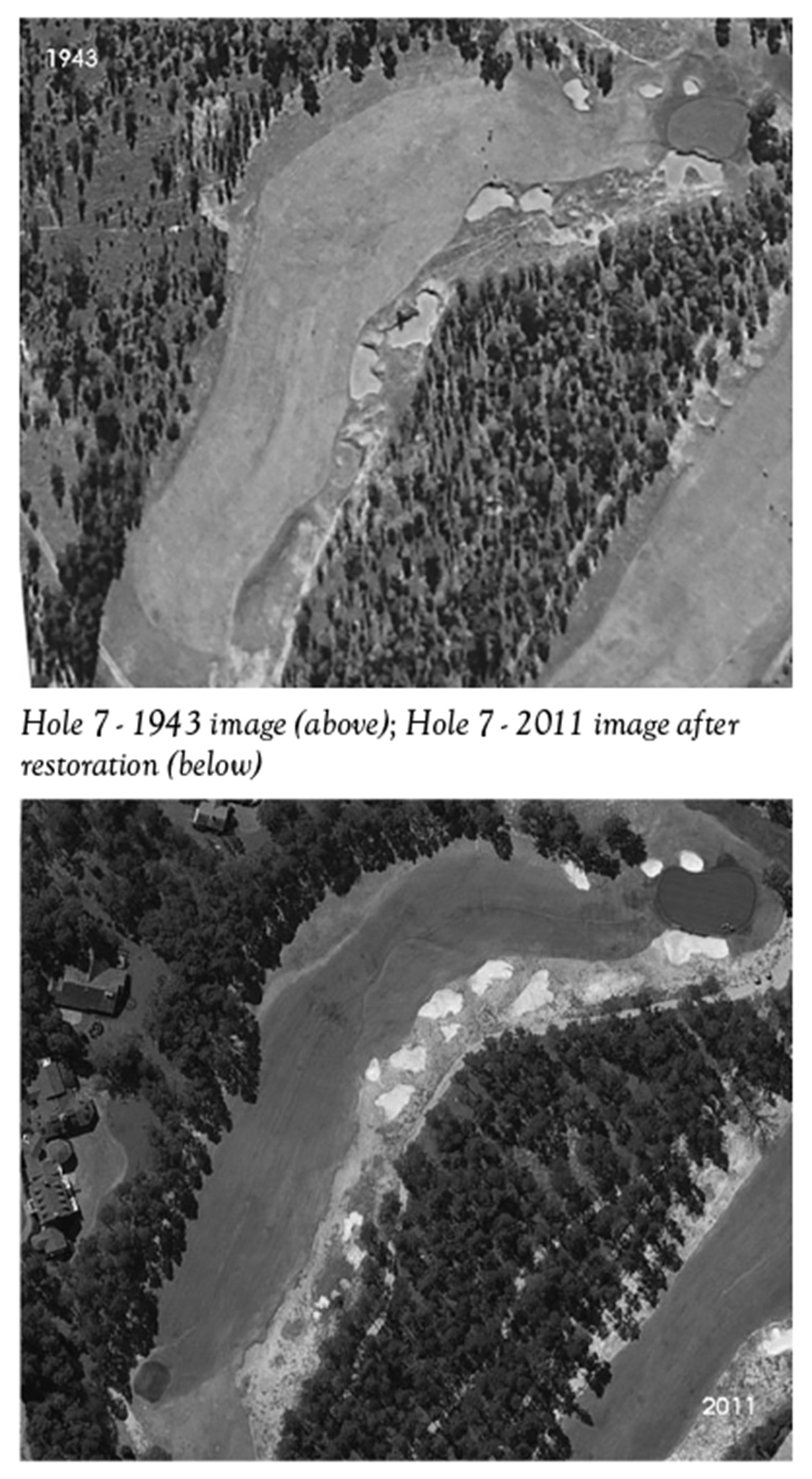

Still, it was a long shot. Even if an aircraft had veered that far west, would the camera have been turned on and clicking after leaving the airspace over the base? Disher found and reviewed the track of a Christmas Day 1943 DOD flight of a plane photographing Fort Bragg. The track showed the plane had, indeed, traveled west toward Pinehurst, reaching the edge of the town before backtracking to Pope. Having identified the flight he was looking for, Disher asked to see the roll that would include the negatives. It would take a week before the roll arrived at NARA. Anxiously, Disher awaited the delivery of the Christmas Day flight photos.

When he finally flashed through the roll, Disher found the images of No. 2. He eyed what were, perhaps, the clearest aerial photos of a golf course he had yet encountered. While aloft over No. 2, the plane had flown lower than was customary. Who knows, maybe the pilot played golf and wanted to take an up-close look at the famous course. Regardless, the details shown of the bunker contouring, tee and green shapes, trees and native areas were strikingly vivid. The aerial camera, clicking away every few seconds, had also captured excellent images of the Pine Needles and Southern Pines courses.

Through a mutual friend, Disher contacted Coore and informed the architect of his find. Arrangements were made for Coore and Crenshaw to stop by Disher’s home in Pinehurst to inspect the photos from the 1943 flight that encompassed the entirety of No. 2. Disher arranged them on his dining room table to appear as a single photograph.

The architects were astonished at what they saw. The photos depicted exactly what they needed to assure themselves they were on the right track. As Crenshaw put it, “it was the confirmation we had been looking for.”

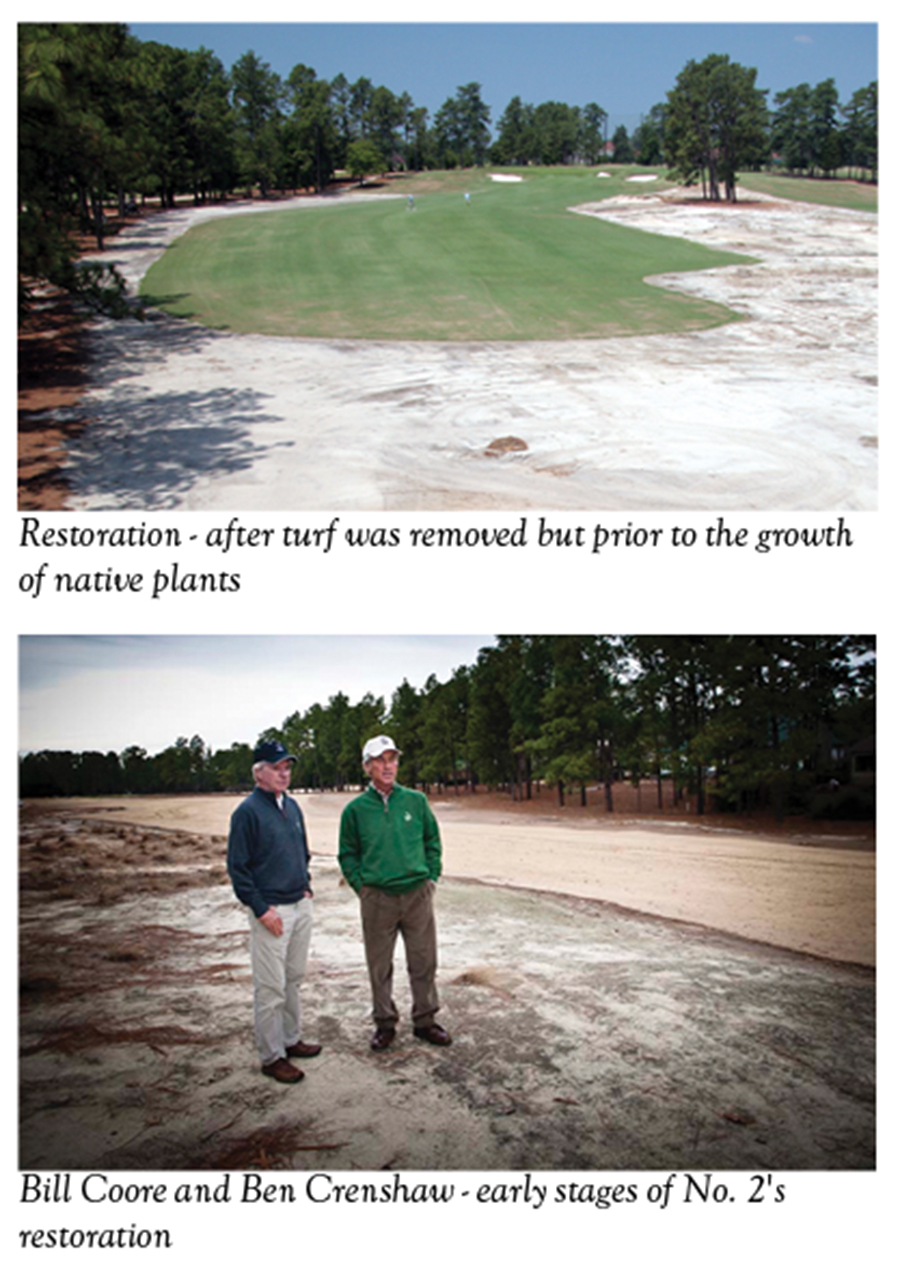

With Disher’s photos serving as their guide, Coore and Crenshaw completed No. 2’s restoration in March 2011. Gone was the matted rough. In its place were the native areas that had characterized Ross’ course. Indigenous plants such as red sorrel, spiderwort and spotted beebalm now grew haphazardly off the fairways. Bunkers were reshaped with the scruffier edges that had marked their appearance in the 1943 aerials. Some bunkers were eliminated, others restored. Several tees were moved to restore the driving challenges Ross had envisioned. Based on the 1943 photograph, the 15th green was widened to its right side by one-third. With areas off the fairway no longer watered, the course looked browner and more natural. Seven hundred of No. 2’s 1,100 sprinkler heads were eliminated, trimming water use in half. Fairways were widened and shaped to approximate their dimensions during the Ross era, thus allowing for alternative routes for approaches into greens.

The restoration was universally praised in golf circles, and the 2014 U.S. men’s and women’s Opens proved to be memorable successes. Fears that the changes to course No. 2 would render it too easy proved overblown. Only three men, including winner Martin Kaymer, and one woman, Michelle Wie, broke par.

“Craig was so instrumental in our work at No. 2,” says Coore of Disher. “I’m not sure we could have accomplished what we did without him.”

Disher became the go-to source for aerial photos of historic courses and has been called upon by architects like Ron Forse, Gil Hanse, Kyle Franz, Jim Urbina and Davis Love Jr. Now 76, Disher is gratified that what began as a pleasant diversion ended up contributing so much to golf. “My research introduced me to some of the nicest people I’ve ever met and taken me to golf courses I never dreamed I would see,” he says. “If you are searching for something you think can’t be found, it probably can be.” PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.