The Evolving Species

Stairway to Heaven

A resting place in life’s long journey

By Claudia Watson

This morning I made a point of waking before sunrise and padding off in a pair of old boot socks to the little deck at my place in Seven Devils, up in the high country. I grabbed a nubby sweater against the air of a late October morning and stepped into the day with my hands wrapped around a cup of hot tea.

A veil of fog clings to the valley at the base of Grandfather Mountain. The distant mountain ridge surrenders to the sunrise, unleashing a canvas of color. This early on a Sunday morning there won’t be many leaf gawkers, and it’s perfect for my journey down a road to a spot that’s become, over 20 years, a pilgrimage.

My husband, Roger, and I would bike a narrow, practically flat paved road that hugs the South Fork of the New River. We’d travel along Railroad Grade Road, a 20-mile trip from the general store in Todd to the tiny community of Fleetwood and back. Our first ride down this road was 23 years ago on an early June morning, riding new cross-country bikes — his, black; mine, green — wedding gifts to each other that spring.

With our lunches and water bottles tucked into our backpacks, we idly explored the winding river valley, protected by steep slopes covered with Christmas tree farms and dotted with old homesteads and lush meadows. A fox looked up, startled from his morning kill. A small herd of whitetail deer dashed from a roadside thicket to the river, nearly knocking me from my bike. We teamed up to shoo a wandering cow back into her pasture, closing the gate behind her.

About midway in our ride, Roger yelled back to me, “Hey babe, look at that,” pointing to a cast concrete stairway leaning against one of two towering tulip poplars. The steps were an invitation to stop and sit a spell in the shade and enjoy the long view of the clear river rambling 30 feet below.

But it was the trees and the placement of the stairs that offered more fascination as they held onto a narrow spit of earth. The one-lane road, which was originally the rail track for the Virginia Creeper, barely squeezed between the river and a rocky outcrop. The only sign of neighbors was a sprawling farmstead at the river’s broad bend, and a tidy brick home tucked into the hillside farther down the road that was guarded by a frisky border collie.

That tiny grass outcropping above the New River became a favorite way station whenever we returned to the high country. Often, after fly-fishing the river or streams nearby, we’d return to the spot, settle into our camp chairs, and enjoy lunch or a late afternoon beer and the constant chatter of life — the hopes, the dreams, the blessings. Even during our winter trips, we’d make time to huddle together on the cold concrete steps, if only for minutes.

It was on a summer’s day while sitting on the steps looking up through the tulip poplar’s canopies — a mosaic of green hues against the blue sky — that I dubbed the location, without much thought, Stairway to Heaven, marking it with a pencil in our dog-eared map book where we cataloged favorite fishing spots and trails.

Though we couldn’t figure out how the steps arrived where they were, we sensed the specialness of the place. Over the course of 20 years or so, the steps became part of our journey. When we arrived at the spot four years ago in October, we saw one of the two tulip poplars was gone, only the stump remaining. Thankfully, the old moss-covered stairway was still there leaning against the solitary tree dressed in its bright yellow glory. We took out our camp chairs to enjoy the sun-kissed day as the leaves danced in the air.

The border collie at the nearby house, less frisky in time, began barking but finally gave up and went to rest with its owner, a silver-haired woman sitting on the porch. I wanted to walk down the road and ask her about the steps, but Roger felt it was intrusive. He preferred our creative musings. With our belongings packed into the car, I gathered a handful of jewel-colored leaves. Roger paused, looking at me, “Hey babe,” he said, motioning me to join him on the steps.

He sat on the top step, and I sat on the one below leaning into him as he wrapped his arms around me. I felt him suck in a deep breath as if to hold back tears, and he buried his head into my neck and whispered, “Babe, you’ve made me so happy. I don’t know how I’d ever go on without you. I love you so much.” We stayed a few minutes, wiped our tears and moved on, waving at the old woman and her dog as we drove off.

On a pretty spring morning the following May, I approached the familiar turn in the road and winced when I saw the stairway and pulled off to the grassy spot. For the first time, I was alone. That past October was our last together. My beloved died the day after Christmas. I pulled the camp chair from the car and sat looking at the river valley bursting with life and hesitated, wondering how I’d ever go on as the tulip poplar’s soft yellow blossoms fell around me.

Then, with a quiet prayer, I opened my hand and let some of him catch the wind and become one with this place — as much as the tulip poplar, the birdsong, and the ancient river. Soon, the little dog down the road began barking. I saw the silver-haired woman on her porch and, without a thought, walked to the edge of her property and asked, “Can you tell me about that spot?” pointing to the tree and the steps. “We’ve been coming here for over 20 years and wondering about those steps.”

Patting her leg, she laughed “Oh, lots of people wonder ’bout them. They came from the house over there,” pointing up the road. “My brother lives there, and he took off a porch and steps, just rested ’em up against the tree years ago.”

It was such an ordinary story.

“Folks come here all the time and take photos sittin’ on the steps,” she added. I told her about our contrived story of a great storm and flood that deposited them in such an unlikely place. “No,” she said with a shake of her head, “the river’s never been that high, honey.”

“We named them the Stairway to Heaven,” I offered.

Her lips broke into a smile, “Well, that’s right nice. I like that.”

I told her that I had lost my husband. “I understand, dear, I lost my husband just five years ago,” she sighed. “Honey, life’s not easy, but this here, it’s a peaceful place until we get up there to see ’em again.”

On an October morning nearly four years later, I am out the door. Navigating the narrow, pothole-strewn road, my heart racing until I turn the last bend and see the tulip poplar and the steps and find my spot under the tree. With nary a breeze, it unleashes a cascade of golden leaves upon me. PS

Claudia Watson is a Pinehurst resident and a longtime contributor to PineStraw and The Pilot

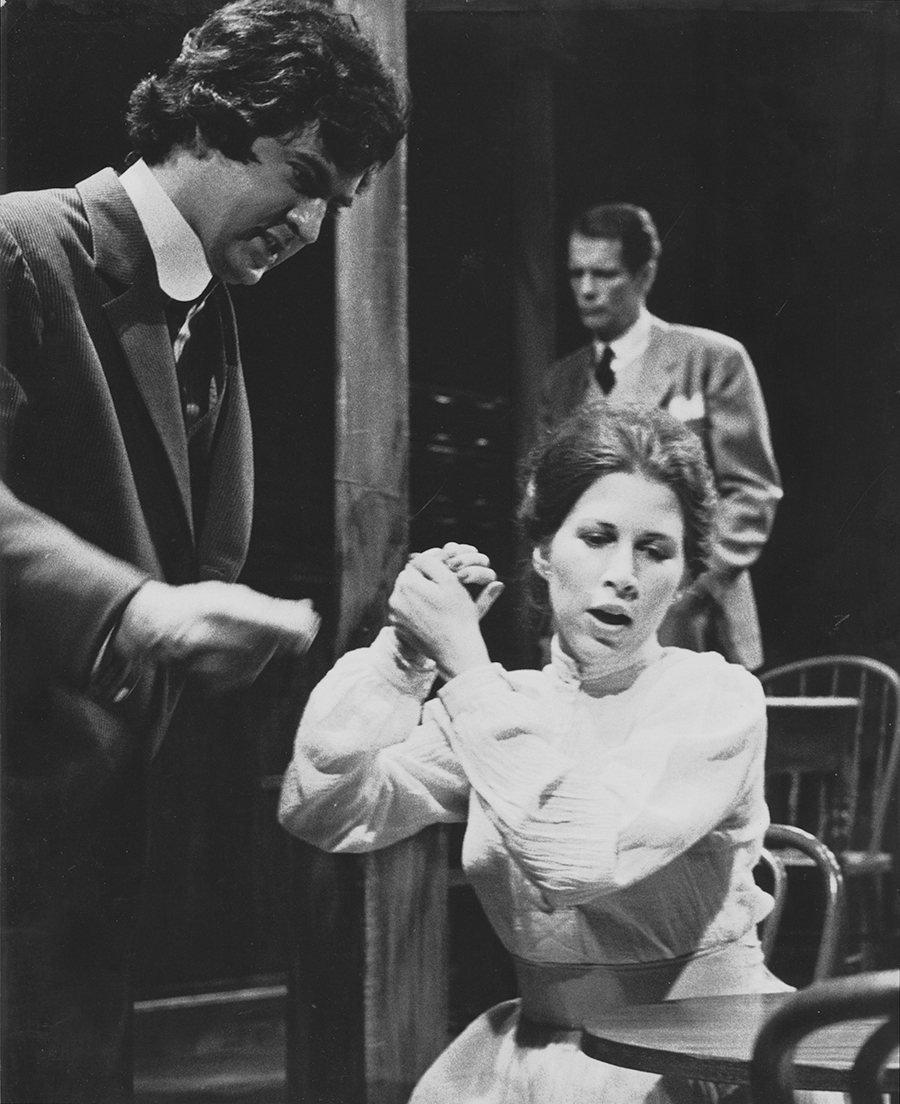

The Gift of Personality

The Gift of Personality

Finding the soul in a role

By Jim Moriarty • Photograph by Tim Sayer

I saw Joyce Reehling at around 3 a.m. She was dressed in white.

Her role in this particular episode of Law and Order was modest. She was a naval officer. All business. But there was something in her eyes, as if, for reasons known only to her, she wasn’t entirely on board with what was happening in that office. She’d had a life before that moment sitting in that chair across that desk from whatever the hell that district attorney’s name is. There was stuff. Maybe stuff she didn’t talk about because, if you’re a female officer in the Navy, maybe you don’t talk about stuff like that, especially if the investigation involves another female naval officer.

And I wondered what it was. And I rearranged the pillow behind my head so I could have a better look.

Reehling doesn’t deliver a line. She pulls back the curtain just a touch to give you a peek through the windowpane, inside the house. Maybe it’s funny. Maybe it’s not. But the one thing it always is, is honest.

Born in Baltimore, Reehling grew up in Laytonsville, once a tiny Montgomery County town that’s gone from the middle of nowhere to a gridlocked prisoner of urban sprawl. “Our huge claim to fame was that the Laytonsville volunteer fire department building burned down once,” says Reehling, who knew she wanted to be an actress from the time she was in kindergarten. “I was in this rhythm band, and I was playing the blocks with sandpaper on them,” she says. “Somebody’s playing the triangle, and we all seemed so happy and I thought, ‘I bet you can do this for a living.’ And I have the musical ability of a dinner plate.”

Reehling’s father, Stanley, who passed away almost two decades ago, was a traveling salesman — insert jokes at your peril — selling institutional food. Her mother, Jean, took care of the home and children. Joyce has a twin sister, Karen, and two younger sisters, Jenny and Mandy, who came along nine and 10 years after the twins. “It was like living in a sorority house interrupted by a father showing up,” she says. “My father was a Marine in the Second World War, God bless him. He spent a part of his life in the South Pacific and China and was a drill sergeant for a while. This is not the building block of great empathy. He wasn’t in the first wave to go into Guadalcanal, but he was there. I’d have to check to find all the places he was, but there was not one that was fun. He was in terrible places doing terrible things, that I know.”

Reehling got her first big break in acting from a wrestling coach. It sounds more violent than it was. She was at Gaithersburg High School and “my guidance counselor, Adam Zetts, was mainly the wrestling coach. Big guy. He didn’t quite know what to make of me. He came to school one day and he saw me in the hall and said, ‘I found it. I found it.’ He’d read a story in the Christian Science Monitor about the North Carolina School of the Arts and he said, ‘I think this is what you need.’”

It was.

“My year was the first full graduating class,” she says. “The school was so new it was like puppies in a box. Now it’s just really together.”

After a fifth year at the School of the Arts as part student, part graduate assistant, it was off to New York. “I still didn’t feel ready,” she says. “The foundation there now is so thorough you should know what you’re doing. Of course, that doesn’t mean you’re not going to be scared. I left the School of the Arts terrified. When I went, you went up on your own. Good luck getting a job. You’re the flotsam and jetsam. It’s very unsettling at first. I think I went to New York with $1,000. I got in the Rehearsal Club, two brownstones up from the Museum of Modern Art. The play and movie Stage Door are based on this place. Carol Burnett had lived there. A whole bunch of women. A lot of Rockettes. Men were not allowed above the first floor. I think we were paying $35 a week. That included breakfast and dinner and linens. I remember a bunch of us having the ubiquitous meeting in a coffee shop where you could have unlimited coffee and everyone got a bagel. That’s a meal. One guy said how fun this phase of life is. I said, ‘I’m OK with it now but at 30 this is going to be really old.’ You were nickel and diming your way through everything.”

Commercials and voice-overs, particularly Reehling’s Robitussin role of Dr. Mom, supported her theater habit. “I always said my job was auditioning, interrupted by work. You were lucky if you had auditions. If you got a play for five or six weeks, whatever it was, you could just about relax into it — but not for long. Oh, this is great. I’m in rehearsal. We opened. It’s going well. What’s my next job? I don’t have one . . . . In the summer I was almost always in a show. I didn’t get to my grandmothers’ funerals because I didn’t have a standby. I had no one to take over so I couldn’t go. Those kinds of things happen. This is what you agreed to when you joined the tribe.”

But the dream job did come along. It was in the Circle Repertory Company, co-founded by a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, the late Lanford Wilson, and director Marshall W. Mason, a member of the Theater Hall of Fame and a recipient of a Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement. Reehling got their attention when she was acting in Wilson’s The Hot l Baltimore on the West Coast.

“Lanford had the ability of creating eight people on stage at one time, and Marshall had the ability to direct eight people on stage at one time. And both of those things are very difficult,” says Reehling. “What Circle Rep did for me was something I really didn’t know I wanted. It put me in a company where there were playwrights who wrote for actors. We had the joy of starting with (a play) from the minute it hit the page.”

Mason, an emeritus professor at Arizona State University, now spends half his year in Mazatlan, Mexico, and the other half in Manhattan. “Lanford wrote Fifth of July with Joyce in mind to play June. I have to say, when we talk about actors at Circle Repertory, the first thing that you’re talking about is a deep honesty. You don’t see acting, the actors become the characters so much. That was the secret of our success. It was true of all our actors. It was certainly true of Joyce. Having said that, what made Lanford especially happy was she knew how to land a line just as the playwright wanted it and score a big laugh. In Fifth of July she brought the house down.”

A couple of years ago Mason called Reehling just to talk about her portrayal of June. “I never discussed this,” says Reehling. “I said to myself in rehearsal, ‘I can’t keep sounding like a shrew.’ I’m always saying something about ‘Let’s get this done. Let’s sprinkle Uncle Matt.’” Her character, June, was intent on scattering Uncle Matt’s ashes. “I came up with a memory. I wore a necklace that nobody saw, little tiny pearls I got in an estate sale or something. I decided that when Uncle Matt was really sick, I came to visit — they more or less raised my daughter. I came to see Matt and he asked to talk to me alone and he was funny like he always was, but he grabbed my arm and he said, ‘Don’t let her keep these ashes too long. Promise me.’ And I promised him. So it wasn’t that I was pushy the way it might appear. Whenever I was on stage, my hand would go here . . . .”

Reehling leans back in her chair and places her hand on an imaginary necklace, as genuine as a recurring dream.

“Oh, it brings tears to my eyes. It’s so real for me. And Marshall didn’t know a thing about that and Lanford didn’t either. Marshall said to me once, ‘What are you using in this moment?’ I said, ‘Do you like it or do you not like it?’ He said, ‘I like it.’ I said, ‘Then I can’t tell you because once I speak it to you, it’s gone.’ I love the secret life. I think every character, every person, we all have secrets all the time, things we don’t say, things we know about ourselves and never want to share. You’ve got to find those things, you must find those things with each person.”

Of course, like an honored houseguest, an actor — even one desperate to work — can overstay his or her welcome inside a character. “The hardest thing in a long run is to know what you know when you know it,” says Reehling, adding a cautionary tale about Carrie Nye from Mary, Mary. “She has a scene where she comes storming in the door, takes off her gloves, throws them down, walks over and says blah, blah, blah, blah, blah and then walks in the bedroom, off stage. She came in one day, took off her gloves, threw them down and said blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, went into the bedroom off stage and walked straight over to the stage manager’s booth and said, ‘I’m giving

notice.’ At intermission she tells the stage manager, ‘Did you realize I wasn’t wearing the gloves?’ She came in, took off gloves she wasn’t wearing, threw them down and didn’t even know she wasn’t wearing them. Time to go.”

Ted Sluberski is an acting instructor in New York City. “I was a very young casting director in the late ’80s, early ’90s. The best thing that could happen to a young casting director was, at one point, Joyce said something to the effect, ‘I think you might be in this for the long run, so I’m going to show you how to talk to an actor.’ And she did. We hit it off like a house on fire. In my now 36 years in the business, the best way to describe Joyce was she did her job to the fullest extent, always. Whether it was a Broadway show, whether it was guest star, whether it was commercials — which are a craft aspect of the business — her commitment to the basic core of acting was consummate. The people who survive in this business are the people who do their job to the hilt. I’ve seen her do some dramatic things. I’ve seen her do some brilliantly comedic things. She always built a person. She didn’t build the idea of someone.”

Reehling and her husband, Tony Elms, the person she refers to as “the most precious man in the world,” have lived in Pinehurst for nearly 10 years. This month she’ll join Sally Struthers (All in the Family, Gilmore Girls) and Kim Coles (Living Single, In Living Color) in the Judson Theatre Company’s October 18-21 production of Love, Loss and What I Wore, by Nora and Dehlia Ephron. It will be the second time Reehling has appeared in one of Judson’s productions, this time with a tad more advance notice.

“Joyce has been like a guardian angel to Judson Theatre Company,” says its founder, Morgan Sills. “I’m not sure everybody realized she had this major past life in New York on television and on the screen working with all these legendary people” (Richard Thomas, Bill Hurt, Swoozie Kurtz, Jeff Daniels, Christopher Reeve, Gig Young, Holly Hunter, Alec Baldwin, Mary Louise Parker, Timothy Hutton, to name a few). Reehling’s first appearance for Judson, however, came straight out of the bullpen. Dawn Wells of Gilligan’s Island fame was cast as Weezer in Steel Magnolias but wound up in the hospital, if just temporarily, instead of on the stage.

“Someone alerted me to Joyce,” says Sills. “She understood the situation. We walked her through it a couple of times and she went on. And she was wonderful.”

Sills thinks the Ephrons’ play is a perfect fit for Reehling. “It’s basically five extraordinary women across the generations, telling the stories, the defining moments, of their lives, via the clothing they had on at the time. So, it’s a piece that shows her tremendous range. Make you laugh; bring a tear to your eye. It’s heartwarming and human and I think it will resonate with everyone. The track of roles Joyce is doing I’ve seen performed by a lot of prodigiously gifted New York actresses, and Joyce is very much in that mold.”

The Reehling/Elms house off Linden Road is filled with art, each piece seemingly with its own secret life. “I love this,” Reehling says, pointing to a painting by James Feehan of figures and poles and shaky equilibrium. “It’s called ‘Tenuous Balance’ and I said, ‘Boy, that feels like my career.’ I wish it had gone on longer. I was never an ingénue, I was always a character girl, and that shortens your life, but women in general have short lives in the theater and film. I can honestly say I can see myself standing in a field near our little red house outside of Baltimore — my father had volunteered us for the job of picking up stones for 25 cents an hour — and I can remember in the back of my head going, ‘How am I going to get from here to where I want to go?’ I didn’t know how I was going to do it, but I did it, one foot in front of the other.” One secret life at a time. PS

Mom, Inc.

Not Picture Perfect

A night at Camp Alternative Universe

By Renee Phile

The four of us pulled into the campground, welcomed by an eerie feeling. The accommodating pictures on the website — the luscious green woods and the thriving campfires — seemed to have been replaced by broken down 1940s campers, scattered trash, clotheslines sagging under the weight of laundry from the Cretaceous Period, a meteor shower of stray cats darting from site to site and, of course, No Trespassing signs.

“This can’t be right,” I said to Jesse, who nodded.

“Should we check in? Or just leave?” he asked.

“I don’t know.”

“This place is weird,” David, 14, piped up from the back seat. “What’s up with all the cats?”

“Let’s just drive around and see if it gets any better,” Jesse, the optimist, said.

As we drove deeper into Camp Backwater, we saw travel trailers, pop-ups, and live-in year-round campers scattered about. Paint peeled from the small houses sitting between them. A cat streaked in front of our car and disappeared.

“This is nothing, and I mean nothing, like the website said it was,” I said. “And it’s not cheap either.”

Though the primitive amenities of the state park down the road now seemed like Shangri-La compared to Camp Irregular Heartbeat, we decided to check in and make an adventure of it. Maybe I could jumpstart a murder mystery.

The lady at the desk, with grey eyes peeking out behind wiry glasses, seemed nice enough until she delivered the worst news David, and his 10-year-old brother, Kevin, could ever possibly hear, “No Wi-Fi for your devices.”

As we cleaned up the trash left from the previous occupants of our campsite, a large, yurt-shaped man shuffled over, shoeless, dressed only in his boxer shorts and what looked like the T-shirt Sonny Corleone was wearing at the tollbooth.

“Hi! I’m Chris! Welcome to the suburbs! Don’t mind the cats. They’re mine. I’ve lived here for over a year. If you need anything, let me know.” Like what? A bell?

A teenager, who seemed to have already dipped heavily into the catnip, sped by on a bike and exclaimed, “I’m too blessed to be stressed! What about you?”

“Might want to stay away from him,” Jesse muttered to the boys as he put a spike in the ground to pitch the tent.

A couple with a small child and a baby pulled their SUV into the site next to us. The baby crawled around in the dirt, while the dad burned through gigabytes of data on his smartphone, Googling “campgrounds near me.” They left in seven minutes.

I decided to walk to the bathhouse. The sanitation grade was “C” for cruddy, and a blue leatherette front seat from a car sat in the middle of the floor, seatbelts dangling. A cat was curled up on top. As I was in the bathroom stall, the cat came in and nuzzled my legs. “Oh, this isn’t weird at all,” I said to the cat which meowed loudly.

That night our fire wouldn’t start. Jesse could make cement blocks burn, so if he can’t get a fire to start, there’s a problem. He dumped an entire bottle of lighter fluid onto the wood. It would flare for a few seconds, then go straight to tiny puffs of smoke. He marched down to the camp store and asked for a refund on the $10 pile of wood. That didn’t burn, either.

Our “neighbors,” led by Chris, drank late into the night, singing the lyrics they could remember to the country songs they thought they knew while the cats meowed in harmony. Shadows passed by our tent every few minutes and Kevin said, “Mom, can I sleep with you?”

In the morning I said a thank you prayer that we all survived. Then we went to a Walmart across the road and bought a board game called “Stuff Happens.” In it each player rates cards from 1-100 on tragic things that might happen to you. It could be as simple as “Lose a Toenail” or as serious as “Lose an Eye.” The other players guess the rating of each card and if you are close, you get the card. The person with the most cards at the end is the winner. I looked through the cards to see if “Stay at a Creepy Campground Infested with Cats” was one of the options.

It was 87. PS

Renee Phile loves being a teacher, even if it doesn’t show at certain moments.

The Omnivorous Reader

Linking Different Worlds

Orr and Sparks connect North Carolina and Africa

By D.G. Martin

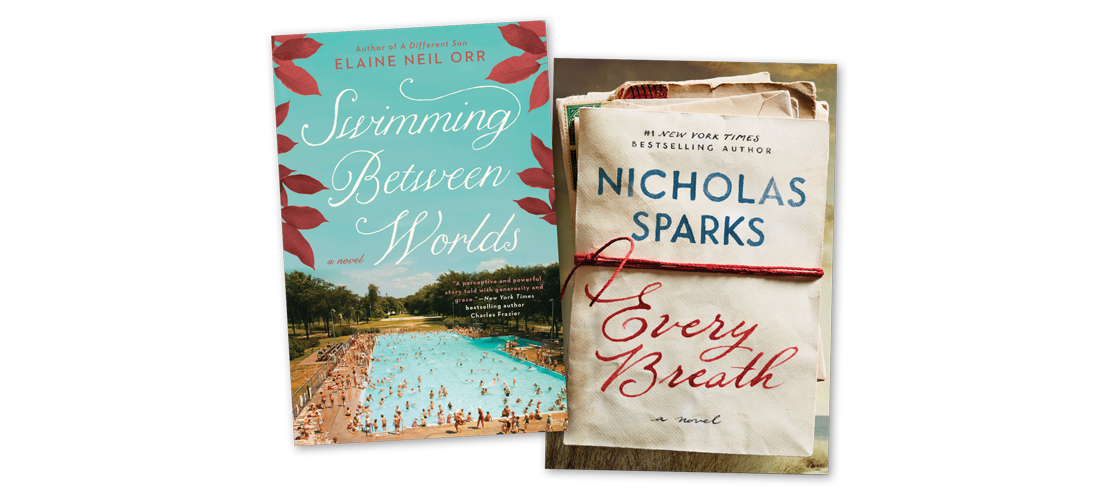

Two important new novels are set in North Carolina and in Africa. It is an amazing coincidence because the books’ authors live in two different literary worlds.

The first new, Africa-connected book is N.C. State professor Elaine Neil Orr’s Swimming Between Worlds. She is a highly praised author of literary fiction.

The second is New Bern — based Nicholas Sparks’ latest, Every Breath, which is being released this month. Sparks’ 20 novels have been regulars on The New York Times best-seller lists, often at No. 1, making him one of the world’s most successful writers of what some call commercial fiction.

What is the difference between literary and commercial fiction? According to Writer’s Digest, “There aren’t any hard and fast definitions for one or the other, but there are some basic differences, and those differences affect how the book is read, packaged, and marketed. Literary fiction is usually more concerned with style and characterization than commercial fiction. Literary fiction is also usually paced more slowly than commercial fiction. Literary fiction usually centers around a timeless, complex theme, and rarely has a pat (or happy) ending. Commercial fiction, on the other hand, is faster paced, with a stronger plot line (more events, higher stakes, more dangerous situations).”

Although both Orr and Sparks would argue that their work cannot be neatly packaged in either genre, the literary/commercial distinction helps prepare readers for the authors’ different styles.

In these two books, both authors tell compelling stories and feature interesting and complex characters.

Orr’s Swimming Between Worlds raises the question of whether there is a connection between the 1950s Nigerian movement for independence and the civil rights movement in Winston-Salem.

Orr grew up as the child of American missionaries in Nigeria. Her experiences gave a beautiful and true spirit to her first novel, A Different Sun, about pre-Civil War Southern missionaries going to black Africa to save souls.

Instead of slaveholding Southerners preaching to Nigerian blacks, the new book contrasts the cultural segregation of 1950s Winston-Salem with the situation in Nigeria. Although Nigerians at that time were coming to a successful end of their struggle for independence from Great Britain, they were still mired in the vestiges of colonial oppression.

Set in these circumstances is a coming-of-age story and a love story. These themes are complicated, and enriched, by the overlay of Nigerian struggles and the civil rights protests in Winston-Salem.

The main male character, Tacker Hart, had been a star high school football player who earned an architectural degree at N.C. State. He was selected for a plum assignment to work in Nigeria on prototype designs for new schools.

Working in Nigeria, this typical Southern white male becomes so captivated by Nigerian culture, religion and ambience that his white supervisors fire him for being “too native” and send him home. Back in Winston-Salem the discouraged and depressed Tacker takes a job in his father’s grocery.

The female lead character, Kate Monroe, is the daughter of a Salem College history professor. Her parents are dead, and after graduating from Agnes Scott College, she leaves Atlanta and her longtime boyfriend, James, to return to Winston-Salem and live in the family home where she grew up. She still, however, has feelings for James, an ambitious young doctor.

How Tacker wins Kate from James is the love story that forms the core of this book. But there are complications created by a young African-American college student who is taking time off to help with family in Winston-Salem. Tacker and Kate first meet Gaines on the same day. After Gaines buys a bottle of milk at the Hart grocery store, white thugs attack him for being in the wrong place (a white neighborhood) at the wrong time. Later on the same day, Kate spots an African-American man holding a bottle of milk, walking by her home in an upper-class white neighborhood. She thinks he probably stole the milk. She is terrified, and immediately locks her doors and windows. She shakes with worry about the danger of this young black man walking through her neighborhood. The young man is, of course, Gaines.

It turns out that Gaines is the nephew of Tacker’s beloved family maid. Tacker and his father hire Gaines to work in the grocery store, and he becomes a model employee.

But Gaines has a secret agenda. He is working with the group of outsiders to organize protest movements at lunch counters in downtown retail stores.

Gaines sets out to entice Tacker to help with the protests, first, only to allow the store to be used at night for a meeting place. Then, over time, Tacker is led to participate in the sit-ins.

In Nigeria, Tacker had found his black colleagues and friends to be just as smart, interesting, and as talented as he was. He found them to be his equals.

Back in Winston-Salem, he has at first slipped back into a comfort level with the segregated and oppressive culture in which he grew up. His protest activities with Gaines put his relationships with his family, Kate and possible employment at an architectural firm at risk.

Tacker’s effort to accommodate his growing participation in the civil rights movement with his heritage of segregation leads to the book’s dramatic, tragic and totally surprising ending.

The African connection in Nicholas Sparks’ new book is Tru Walls, a white safari guide from Zimbabwe, formerly Rhodesia. In 1990, the 42-year-old Tru comes to Sunset Beach to meet his biological father. It is his first visit to the United States. On the beach he meets Hope Anderson, a 36-year-old nurse from Raleigh. She is in a long-term relationship with Josh, a self-centered orthopedic surgeon. Nevertheless, she and Tru immediately fall into a deeply passionate love affair.

How Hope resolves her competing feelings for Tru and Josh is the thread that guides the book to a poignant conclusion 24 years later at another North Carolina beach.

In the meantime readers learn from Tru’s experiences about the lives of white farm families and the competing claims of the overwhelming black majority in Zimbabwe. Sparks’ descriptions of wildlife and the safari experience evoke memories of Ernest Hemingway’s African short stories.

Sparks’ publishers say that Every Breath is in the spirit of The Notebook. In both books, the lovers’ early encounters involve fiery and youthful passion. Sparks brings them together again years later as older, even infirm, people still deeply in love.

PBS’s Great American Read has named The Notebook one of America’s 100 best-loved novels. It’s the only book set in North Carolina to make the list. On Oct. 23, PBS will announce the one book selected as America’s best-loved novel.

Voting will be open until Oct. 18. You may register your votes for The Notebook and for other books on the list. Go to www.pbs.org/the-great-american-read/vote/. For a list of all 100 books, go to www.pbs.org/the-great-american-read/books/#/.

As part of its participation in The Great American Read during the first two weeks in October, UNC-TV will air special “North Carolina Bookwatch” interviews with Sparks about The Notebook and Every Breath. PS

D.G. Martin hosts “North Carolina Bookwatch,” which airs Sundays at noon and Thursdays at 5 p.m. on UNC-TV.

Wine Country

The Chardonnay Way

Finding the right fit for fall

By Angela Sanchez

There are as many reasons why so many people, in so many places, love chardonnay as there are, well, chardonnays. It’s highly adaptable and easily grown in many soil types and climates. It’s easily influenced by where it’s grown and by the winemaker’s hands, with as many styles and price points as its broad range of appeal would suggest. But does anyone really know what chardonnay should taste like? If we compare chardonnay-to-chardonnay (like apples-to-apples), there are styles ranging from Golden Delicious to Pink Lady to Granny Smith. If you like big, rich, round and citrus; or bold, oaky and tropical; or lean, mineral lemon-lime characters (my favorite), there is a chardonnay for you. Oak bomb, butter bomb, or classically elegant and restrained, chardonnays in all these forms, and more, are out there.

Chardonnay’s origin is in the Burgundy region of France, where I believe it’s at its very best. Burgundy is where you find chardonnay based on true terroir. In Chablis, a cool climate with limestone soil, the chardonnay is crisp, lean and clean. Minimal oak aging is used. Those who like Domaine Dauvissat use it as a complement to the natural flavors of chardonnay and to round out its natural acidity, pronounced by Chablis’ cool climate. Others, like Domaine Louis Michel & Fils, use no oak on any of their chardonnays, leaving them in their pure form, racy and mineral driven. A mix of soil types and elevation in Burgundy make the malleable chardonnay grape show different characteristics from one growing region to the next. In Meursault, chardonnay is rich, buttery with some honeyed notes, while in the neighboring region of Puligny-Montrachet, hazelnut, lemongrass and green apples are the primary characteristics. North of Burgundy in Champagne, we find chardonnay used as a blending grape in styles like brut and sec. Or it can stand alone in its yeasty, nutty, racy beauty in blanc de blanc, a 100 percent chardonnay. In regions with cooler climates and limestone-driven soils, chardonnay lends structure and backbone to the blends and bright, focused acidity to the blanc de blancs.

Chardonnay is grown all over the world, in warm climates, cool climates and those that have heavy coastal influences. Each country and region produces a chardonnay of a different flavor. Add the light or heavy hand of a winemaker and chardonnay becomes something else altogether. California chardonnay is a great example. Cooler climates in Northern California, like Carneros, produce chardonnay with higher acid and more structure than those from warmer climates in the south around Santa Barbara and Santa Lucia Highlands. Whether naturally higher in acid or more round and lush (depending on the growing region), the winemaker can greatly influence the wine as well. For many years winemakers in the New World were heavy-handed with oak “treatments,” or aging in barrels and manipulating the fermentation process, creating wines that were overly weighty, with buttery notes and vanilla, or predominantly oaky. Big, mostly over-the-top California chardonnay became the norm. Nowadays winemakers show more restraint with their influence on the wines, resulting in cleaner styles that allow consumers to taste a difference from region to region based on elevation, climate and soil — the terroir. The trend is due both to consumers’ move to a fresher, lighter style of chardonnay and to their consumption of imported chardonnay from areas like France and Italy. Winemakers are also keen to let their region, vineyard and their own house style show through rather than producing and manipulating chardonnay to be oaky, buttery and slightly sweeter.

Something about chardonnay has always reminded me of fall; maybe it’s the golden-hued color, like the turning leaves and afternoon autumn sun. With cooler weather, I still like to drink white wines, maybe just not as crisp and light as in late spring and summer — something with a bit more weight and viscosity. Enter chardonnay. As a personal preference I choose to drink Burgundy. If I’m going big on spending and style, I’ll choose a Chablis or Puligny Montrachet or, for something more budget-friendly and offering a lot of wine for the money, a selection from the Mâconnais or Côte Chalonnaise. As always, I add a cheese to snack on with the wine. Stick to the old saying “if it grows together it goes together.” Triple cream Brie, with fresh cream added during the production process, produces a spreadable butter-like cheese that matches nicely. Brillat-Savarin cheese made in the Burgundy region is a classic example of the triple cream style. Small wheels, about one pound in weight, made from cow’s milk with a bloomy white rind, resemble perfect little cakes when whole and fresh. Cut into them and you’ll find a delicate soft cheese with sweet butter and slightly nutty notes. A little stronger cheese, but still with the same elegance and beauty, is Delice de Bourgogne. The addition of cream fraiche to the cheese makes it even more decadent and luscious with added notes of mushrooms and earth. Not to mention it is a dream companion with Champagne.

As you ponder the rows and rows of chardonnay at your local wine shop, or the wine list at your favorite restaurant, be bold and try something new. If you always drink California chardonnay, try Burgundy. Or vice versa. Grab some triple cream Brie and you just might find a chardonnay style that’s right for you. PS

Angela Sanchez owns Southern Whey, a cheese-centric specialty food store in Southern Pines, with her husband, Chris Abbey. She was in the wine industry for 20 years and was lucky enough to travel the world drinking wine and eating cheese.

Poem

Hickory Nut Falls

The wind says, Breathe into the sting,

but the mind anticipates the hive.

Each day bears a lesson.

In my room, where the dry leaves know the secret to eternal life

and the acorn shows me how to stand tall, I search for the gorge,

cool patches of earth like open mouth kisses.

There is no separation.

Papa used prayer, sat in his threadbare chair,

each labored breath a short infinity; each day a gift.

At the water’s edge, I see him as a young man,

feet bare, toes crooked like mine,

working a smooth stone between his fingers

like a talisman to a timeless space.

Ankles numb in the flowing river that connects us,

I stand there as he sends the stone dancing across the water’s surface,

feel the ripples expand within me, remember the calm of his voice:

I am always with you. We are always home.

—Ashley Wahl

Accidental Astrologer

Stars and Star-Makers

Dazzling, yet old-fashioned, Librans treasure their nearest and dearest

By Astrid Stellanova

Star Children, our October-born enjoy longer lives and a better chance of becoming President; they are more romantic and athletic than the rest of us average Joes. Famous October babies are either stars themselves or star-makers: Julie Andrews, Kim Kardashian and that acid-tongued Simon Cowell with the angelic grin.

Pumpkins, bonfires and harvest moons are enough to make anyone grin; if not, then you may be an alien child. Before sending your DNA off to Ancestry.com, consider that our ancestors celebrated the deep connection with Mother Earth in late fall and were grateful for this golden time. As the days grow shorter, enjoy hearth and home — and chill, Baby. — Ad Astra, Astrid

Libra (September 23–October 22)

There’s no shame in your game, Sugar. You are old-fashioned, just as accused. But you know how to love what you have and to make your nest a welcoming and special place. When you take stock of all the things in your plus column, notice how many old friends and long relationships you have made. That, Birthday Child, is a fine gift.

Scorpio (October 23–November 21)

You’re tetchy, and more self-critical than normal. Don’t shave an eyebrow off trying to fix a tee-ninesy mistake. Nobody else sees you through the same harsh lens. In fact, those who know you feel they can’t live up to your standards. Relax, Honey, and realize you are no ordinary creature.

Sagittarius (November 22–December 21)

Somebody you trust seems to be goading you toward a step you don’t want to take. Don’t that just grind your gears? Are they friend or frenemy? Buttercup, hitch up your britches and grin and bear it. They mean well, they just don’t speak your language.

Capricorn (December 22–January 19)

Hearing the truth is like drinking from a firehose. Hard to swallow. Hurts. Yep. But here you are, swallowing another needed dose of reality. Now, Honey, it will require you to take another step and face one more test of your resolve and backbone.

Aquarius (January 20–February 18)

You’ve had to power through a challenge that tested your nerve — and sexy verve — on every level. But in the background, an ally has got your back like a wool sweater. They know you better than you know yourself, and don’t want to see you fail.

Pisces (February 19–March 20)

You took two steps forward and one backwards in a weird shuffle regarding health matters. Is Chick-fil-A your secret sponsor? Your devotion to habit and fast foods are at war with your best interests. Something has to give, Sugar. (And sugar and fried food are a good start.)

Aries (March 21–April 19)

False flattery is no reason to marry a prison pen pal. The power of a good line is indisputable, but Darling, you can’t trust your bedazzled self this month. Snap out of it and ask yourself why you need a yes man or woman so much.

Taurus (April 20–May 20)

Open mouth and exchange feet, Sugar. If you weren’t so charming, a lot of your best pals would not be so forgiving. If you can do one more crucial thing, Sugar Pie, share the credit for a project completed and don’t hog all the credit. Baby steps.

Gemini (May 21–June 20)

Lordamercy! Take the next exit off the Ho Highway. Have you lost your grip? Think nobody has noticed? Well, Darling, they did. I’m not saying your standards are slipping, I’m saying they have conveniently disappeared. Chin up, head high and don’t look back!

Cancer (June 21–July 22)

Sugar, time to learn how to mine gold from whatever you learned from whoever ticked you off. Actually, a few too many did. You’ve been unable to settle, get rest, find a comfy place with yourself lately and it’s taking a toll. Turn that crazy train around.

Leo (July 23–August 22)

Is Boss Hog your role model? If you watch TV, you begin to think that everybody has lost their ever-loving minds. Raised voices don’t make for stronger arguments, Honey. Somebody has to set a better example — and why not a natural leader like you?

Virgo (August 23–September 22)

Feeling duller than a plastic fast-food knife? By the end of the summer days, you’ve battled to get your game back. Mix and mingle with a friend you look up to, and energize yourself again. You are very affected by the company you keep. OH

For years, Astrid Stellanova owned and operated Curl Up and Dye Beauty Salon in the boondocks of North Carolina until arthritic fingers and her popular astrological readings provoked a new career path.

House of Sweet Surprises

House of Sweet Surprises

Designer Mark Parson’s imaginative reworking of a humble bungalow creates something for everyone

By Deborah Salomon • Photographs by John Gessner

If the shoemaker’s children shouldn’t go barefoot, neither must an architectural designer’s family suffer an ordinary house. What Mark and Kathie Parson have done to a humble 1940s bungalow on the outskirts of the village of Pinehurst is the glass slipper on Cinderella’s sooty foot, the genie in the mayonnaise jar. Not only has Mark designed a compound housing three generations, he has paid homage to the St. Andrews Links in Scotland by reproducing narrow, curving canals through which flow gurgling water, set on putting-green grass, in a rear courtyard.

He also designed and installed the landscaping, including details like leaving a narrow band of soil between a brick walkway and low wall, allowing ficus vines to root and creep.

“Houses don’t have DNA,” he reasons. “We had to give it character.” Knocking the bungalow down would have been easier. “But then you wouldn’t have a good story.”

Mark Parson is full of surprising stories, starting with self-training. Then, his unlikely success, evidenced by hardscape and softscape designs for Sandals Caribbean resorts, Miami Beach mansions and a prize-winning Harley-Davidson dealership. Locally, besides residential projects, he transformed an unsightly garage on Broad Street into The Sly Fox gastropub.

To Kathie go accolades for the floorplan and décor, her taste honed as a designer/manager at Bloomingdale’s in Miami, where they met. Kathie is from Minnesota, Mark from (he wrinkles his nose) Ohio. She grew up in an apartment; he in “a shoebox.” His upward mobility could have been written by Twain, or O. Henry. In part: “My father was a union guy at Chrysler. I framed houses, worked in a sheet metal shop, welded, worked as an orthodontist’s assistant —all that hands on stuff.” But, despite dream jobs like being flown back and forth to Sandals Royal Bahamian Resort in Nassau, he and Kathie, new parents after many years of marriage, opted out of the glam lane and chose North Carolina — first Shelby, then Asheboro. While participating in a Richard Petty charity ride, Mark discovered Pinehurst. “I had heard of (Frederick Law) Olmsted. The real draw was sandy soil and people from everywhere.” People who appreciated and could afford imaginative renovations/new construction.

Kathie looked at the village of Pinehurst, drove over to Southern Pines and decided this was where she wanted to be a stay-home mom.

In 2003, they bought two houses on Everette Road, one for them, one for Kathie’s mother. The plan: Put both on the market and remodel the one that didn’t sell.

Remodel is hardly the word. Mark, as architect and general contractor, took the 1,100-square-foot house down to the studs and dirt floor. The phoenix that arose, double in size, had a new wing, a living room delineated by columns, a kitchen with corner banquette eating area but, strangely, no dining room.

“We eat everywhere,” Kathie says. Walkabout fajita parties inside and out are more likely than sit-down dinners. One Thanksgiving they served on the front patio, which has a fireplace, and beside it, a salad garden. Out back, beyond the reflecting pool, is another dining area with grill and wood-fired pizza oven.

The reasoning goes deeper. In the dining room space stands a grand piano played by 18-year-old Wyatt, a serious musician who started on a keyboard and progressed to this magnificent instrument. Beyond it, windows and doors overlook the grassy courtyard. Entering the front door, a person’s eye is drawn forward by the piano and beyond, to the garden, which was Mark’s intention. A hallway to the right — previously two bedrooms and bath — has been reconfigured as a master suite with dressing room and Kathie’s office. In the bedroom, wide-board knotty pine floors used elsewhere yield to velvety-thick moss green carpet, the whole resembling a fine hotel.

“People gravitate to the kitchen,” Mark continues. With this in mind, he designed a beauty and elled a wing around it with two more bedrooms, a bath and moderately sized den.

The moss green coloration that permeates each room has followed them from house to house. Kathie finds it soothing. She drew complementary forest tones from a printed fabric brought from Florida and used to upholster the breakfast room valance. Even the granite kitchen island has a green-gray tinge. Elsewhere, old leather couches, rather formal tables and chests, and heavy sateen drapes convey elegance. Kathie and Mark both prefer mahogany and other dark woods for their richness and antiquity which, Mark says, echoes Pinehurst. In contrast, rather than elaborate crown moldings and door frames, Mark chose simple flat stock painted a darker green, while several chairs upholstered in bold stripes speak contemporary Scandinavian. Art is mainly florals or landscapes, which blend with upholstery and rug patterns.

Although family heirlooms aren’t part of the scene, Kathie and Mark planned a kitchen alcove to accommodate a massive sideboard Mark’s mother painted. Above it, a blackboard framed in curlicue gold announces the dinner menu: wood-fired pizza.

Every designer has a signature that follows him or her from project to project. Mark is a ceiling guy. “I want people to look up. Why do you think churches have steeples?” Angles and vaults have become his trademark — in the family room, paneled in cedar, they suggest a dome. The living room gabled ceiling is accomplished with cottage-y painted tongue-and-groove boards. Mark indulged himself with the curving canals bisecting the courtyard, strewn with bocce balls, also a tiny waterfall on the front walkway, because he likes the sound. He tucked two butler’s pantries into the layout and, as the family cook, fine-tuned the kitchen.

The sweetest surprise stands beyond the back gallery: a free-standing storybook Nantucket cottage with flowers spilling from window boxes. Mark built it for his beautiful 82-year-old mother, Ila Parson.

“She raised me,” he says, reverently. “I can see her when I’m standing at the kitchen sink and she’s sitting in her living room. We wave every night before I go to bed.”

Family dynamics influenced the project. Ila Parson lives independently with a 17-year-old teacup poodle. She drives her own car, prepares most of her meals and walks miles every day. “We’re careful not to get in each other’s way,” Ila says. Kathie adds, “Mark had to think how to incorporate his mother’s lifestyle with ours, our son and his friends.”

Ila’s most frequent visitor is grandson Wyatt; proximity has fostered a close relationship.

Ila prepared for the move by getting rid of almost everything in her Village Acres house, then choosing simple new furnishings in refreshing blue, white and gray. The 740-square-foot cottage has one bedroom with, typically, a vaulted ceiling; a bathroom, kitchen with breakfast bar, sitting room and screened porch. Tucked behind the main house, this tiny domain is quiet and practically invisible from the street.

Barefoot? Hardly. A smart shoemaker’s children wear his best styles for all to see, to covet. Mark Parson’s home and grounds showcase his design capabilities for customers. Otherwise, Kathie says, “This house is everything we didn’t have.”

Remember, Mark’s goal was to create a story for a house that — unlike others in historic Pinehurst — had none.

Obviously, he succeeded. PS

Birdwatch

Jay Day

There’s more to the ubiquitous blue jay than meets the eye

By Susan Campbell

The blue jay is one of those species most of us can instantly recognize. But how well do we really know this medium-sized raucous bird found at feeders or flying around in the treetops at any time of the year? Though their behavior may not seem particularly remarkable at first glance, they are complex and unique creatures.

Jays are closely related to crows, a highly evolved species. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that they exhibit an advanced degree of intelligence and have complex social systems. Blue jays remain together as a family for a relatively long period and also mate for life. And here’s a species that communicates not only with their voices but also with body language. The telltale bristling of a jay’s crest is one of the most obvious ways they express themselves. Look for a raised crest whenever an individual is alarmed or intimidated.

Although the bird’s underparts are a dingy gray, the jay’s bright blue coloration and its distinctive blue crest give the bird a cocky, imperious air. A unique brindling pattern specific to individuals also makes each bird distinctive. (Interestingly the pigment found in jay feathers is produced by melanin, which is actually brown. It is the structures on the barbs of the bird’s feathers that cause light to reflect in the blue wavelength.)

In addition to their bright coloration, jays attract attention with their loud and piercing calls. They make a variety of unusual squawks and screams, often from a perch high in the canopy. Jays are well known for mimicking other birds’ calls: especially hawks. Whether this is an alarm tactic or whether they are trying to fool other species is not clear. The great early ornithologist John Audubon interpreted this behavior as a ploy that allowed blue jays to rob nests of smaller birds, such as warblers and vireos that instinctively scatter whenever they hear the terrifying sound of a hawk hunting for prey. But modern studies of blue jay diets have not found that eggs or nestlings are particularly common foods.

Another mystery is why, in some years, these birds migrate. Blue jays are particularly fond of acorns. It may be that in years when oaks here are not very productive, jays move southward in search of their favorite food. So the number of blue jays that remain in the Piedmont and Sandhills this winter will likely depend on the mast crop — especially the abundance of white oak acorns. These acorn-lovers have a specialized pouch in their throats for carrying acorns and other large edibles, which they stash in holes and crevices for later delectation.

Blue jays also have interesting nesting habits. While males collect most of the materials — live twigs, grasses and rootlets — females create a large cup, where they incubate and brood the young birds. All the while the male feeds the broodking female — and then forages for the tiny hatchlings. Once the young have developed a good layer of down, the female will join the search for food for the family. It is not unusual for young jays to wander away from the nest before actual fledging occurs. But the wise parents are not likely to feed the begging youngsters unless they return to the nest. It is during this period that some people are convinced they need to “rescue” the wayward youngsters.

Finally, reports of “bald” blue jays are not uncommon. Do not be surprised if you see an odd-looking individual at a feeder or bird bath with virtually no feathers on its head: just dark skin. At first this was thought to be caused by feather mites that can be found on all birds to varying degrees. But now it seems there are simply individuals that lose all of their head feathers at once instead of in the normal, staggered fashion. It appears this is more likely in adolescents who are undergoing their very first molt

The next time you notice one of these noisy, crested birds take a closer look. Blue jays are fascinating — and full of surprises! PS

Susan would love to receive your wildlife sightings and photos. She can be contacted by email at susan@ncaves.com, or by calling (910) 585-0574.