The Gift of Personality

Finding the soul in a role

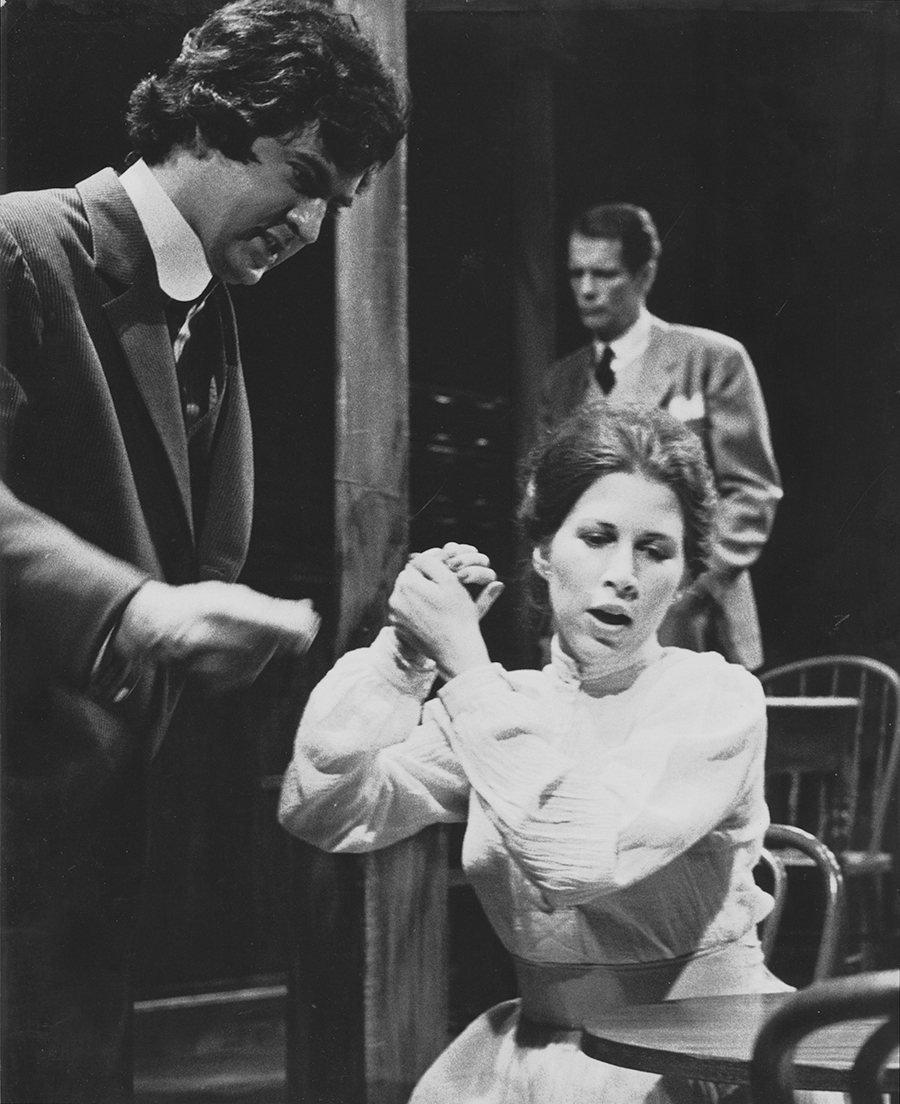

By Jim Moriarty • Photograph by Tim Sayer

I saw Joyce Reehling at around 3 a.m. She was dressed in white.

Her role in this particular episode of Law and Order was modest. She was a naval officer. All business. But there was something in her eyes, as if, for reasons known only to her, she wasn’t entirely on board with what was happening in that office. She’d had a life before that moment sitting in that chair across that desk from whatever the hell that district attorney’s name is. There was stuff. Maybe stuff she didn’t talk about because, if you’re a female officer in the Navy, maybe you don’t talk about stuff like that, especially if the investigation involves another female naval officer.

And I wondered what it was. And I rearranged the pillow behind my head so I could have a better look.

Reehling doesn’t deliver a line. She pulls back the curtain just a touch to give you a peek through the windowpane, inside the house. Maybe it’s funny. Maybe it’s not. But the one thing it always is, is honest.

Born in Baltimore, Reehling grew up in Laytonsville, once a tiny Montgomery County town that’s gone from the middle of nowhere to a gridlocked prisoner of urban sprawl. “Our huge claim to fame was that the Laytonsville volunteer fire department building burned down once,” says Reehling, who knew she wanted to be an actress from the time she was in kindergarten. “I was in this rhythm band, and I was playing the blocks with sandpaper on them,” she says. “Somebody’s playing the triangle, and we all seemed so happy and I thought, ‘I bet you can do this for a living.’ And I have the musical ability of a dinner plate.”

Reehling’s father, Stanley, who passed away almost two decades ago, was a traveling salesman — insert jokes at your peril — selling institutional food. Her mother, Jean, took care of the home and children. Joyce has a twin sister, Karen, and two younger sisters, Jenny and Mandy, who came along nine and 10 years after the twins. “It was like living in a sorority house interrupted by a father showing up,” she says. “My father was a Marine in the Second World War, God bless him. He spent a part of his life in the South Pacific and China and was a drill sergeant for a while. This is not the building block of great empathy. He wasn’t in the first wave to go into Guadalcanal, but he was there. I’d have to check to find all the places he was, but there was not one that was fun. He was in terrible places doing terrible things, that I know.”

Reehling got her first big break in acting from a wrestling coach. It sounds more violent than it was. She was at Gaithersburg High School and “my guidance counselor, Adam Zetts, was mainly the wrestling coach. Big guy. He didn’t quite know what to make of me. He came to school one day and he saw me in the hall and said, ‘I found it. I found it.’ He’d read a story in the Christian Science Monitor about the North Carolina School of the Arts and he said, ‘I think this is what you need.’”

It was.

“My year was the first full graduating class,” she says. “The school was so new it was like puppies in a box. Now it’s just really together.”

After a fifth year at the School of the Arts as part student, part graduate assistant, it was off to New York. “I still didn’t feel ready,” she says. “The foundation there now is so thorough you should know what you’re doing. Of course, that doesn’t mean you’re not going to be scared. I left the School of the Arts terrified. When I went, you went up on your own. Good luck getting a job. You’re the flotsam and jetsam. It’s very unsettling at first. I think I went to New York with $1,000. I got in the Rehearsal Club, two brownstones up from the Museum of Modern Art. The play and movie Stage Door are based on this place. Carol Burnett had lived there. A whole bunch of women. A lot of Rockettes. Men were not allowed above the first floor. I think we were paying $35 a week. That included breakfast and dinner and linens. I remember a bunch of us having the ubiquitous meeting in a coffee shop where you could have unlimited coffee and everyone got a bagel. That’s a meal. One guy said how fun this phase of life is. I said, ‘I’m OK with it now but at 30 this is going to be really old.’ You were nickel and diming your way through everything.”

Commercials and voice-overs, particularly Reehling’s Robitussin role of Dr. Mom, supported her theater habit. “I always said my job was auditioning, interrupted by work. You were lucky if you had auditions. If you got a play for five or six weeks, whatever it was, you could just about relax into it — but not for long. Oh, this is great. I’m in rehearsal. We opened. It’s going well. What’s my next job? I don’t have one . . . . In the summer I was almost always in a show. I didn’t get to my grandmothers’ funerals because I didn’t have a standby. I had no one to take over so I couldn’t go. Those kinds of things happen. This is what you agreed to when you joined the tribe.”

But the dream job did come along. It was in the Circle Repertory Company, co-founded by a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, the late Lanford Wilson, and director Marshall W. Mason, a member of the Theater Hall of Fame and a recipient of a Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement. Reehling got their attention when she was acting in Wilson’s The Hot l Baltimore on the West Coast.

“Lanford had the ability of creating eight people on stage at one time, and Marshall had the ability to direct eight people on stage at one time. And both of those things are very difficult,” says Reehling. “What Circle Rep did for me was something I really didn’t know I wanted. It put me in a company where there were playwrights who wrote for actors. We had the joy of starting with (a play) from the minute it hit the page.”

Mason, an emeritus professor at Arizona State University, now spends half his year in Mazatlan, Mexico, and the other half in Manhattan. “Lanford wrote Fifth of July with Joyce in mind to play June. I have to say, when we talk about actors at Circle Repertory, the first thing that you’re talking about is a deep honesty. You don’t see acting, the actors become the characters so much. That was the secret of our success. It was true of all our actors. It was certainly true of Joyce. Having said that, what made Lanford especially happy was she knew how to land a line just as the playwright wanted it and score a big laugh. In Fifth of July she brought the house down.”

A couple of years ago Mason called Reehling just to talk about her portrayal of June. “I never discussed this,” says Reehling. “I said to myself in rehearsal, ‘I can’t keep sounding like a shrew.’ I’m always saying something about ‘Let’s get this done. Let’s sprinkle Uncle Matt.’” Her character, June, was intent on scattering Uncle Matt’s ashes. “I came up with a memory. I wore a necklace that nobody saw, little tiny pearls I got in an estate sale or something. I decided that when Uncle Matt was really sick, I came to visit — they more or less raised my daughter. I came to see Matt and he asked to talk to me alone and he was funny like he always was, but he grabbed my arm and he said, ‘Don’t let her keep these ashes too long. Promise me.’ And I promised him. So it wasn’t that I was pushy the way it might appear. Whenever I was on stage, my hand would go here . . . .”

Reehling leans back in her chair and places her hand on an imaginary necklace, as genuine as a recurring dream.

“Oh, it brings tears to my eyes. It’s so real for me. And Marshall didn’t know a thing about that and Lanford didn’t either. Marshall said to me once, ‘What are you using in this moment?’ I said, ‘Do you like it or do you not like it?’ He said, ‘I like it.’ I said, ‘Then I can’t tell you because once I speak it to you, it’s gone.’ I love the secret life. I think every character, every person, we all have secrets all the time, things we don’t say, things we know about ourselves and never want to share. You’ve got to find those things, you must find those things with each person.”

Of course, like an honored houseguest, an actor — even one desperate to work — can overstay his or her welcome inside a character. “The hardest thing in a long run is to know what you know when you know it,” says Reehling, adding a cautionary tale about Carrie Nye from Mary, Mary. “She has a scene where she comes storming in the door, takes off her gloves, throws them down, walks over and says blah, blah, blah, blah, blah and then walks in the bedroom, off stage. She came in one day, took off her gloves, threw them down and said blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, went into the bedroom off stage and walked straight over to the stage manager’s booth and said, ‘I’m giving

notice.’ At intermission she tells the stage manager, ‘Did you realize I wasn’t wearing the gloves?’ She came in, took off gloves she wasn’t wearing, threw them down and didn’t even know she wasn’t wearing them. Time to go.”

Ted Sluberski is an acting instructor in New York City. “I was a very young casting director in the late ’80s, early ’90s. The best thing that could happen to a young casting director was, at one point, Joyce said something to the effect, ‘I think you might be in this for the long run, so I’m going to show you how to talk to an actor.’ And she did. We hit it off like a house on fire. In my now 36 years in the business, the best way to describe Joyce was she did her job to the fullest extent, always. Whether it was a Broadway show, whether it was guest star, whether it was commercials — which are a craft aspect of the business — her commitment to the basic core of acting was consummate. The people who survive in this business are the people who do their job to the hilt. I’ve seen her do some dramatic things. I’ve seen her do some brilliantly comedic things. She always built a person. She didn’t build the idea of someone.”

Reehling and her husband, Tony Elms, the person she refers to as “the most precious man in the world,” have lived in Pinehurst for nearly 10 years. This month she’ll join Sally Struthers (All in the Family, Gilmore Girls) and Kim Coles (Living Single, In Living Color) in the Judson Theatre Company’s October 18-21 production of Love, Loss and What I Wore, by Nora and Dehlia Ephron. It will be the second time Reehling has appeared in one of Judson’s productions, this time with a tad more advance notice.

“Joyce has been like a guardian angel to Judson Theatre Company,” says its founder, Morgan Sills. “I’m not sure everybody realized she had this major past life in New York on television and on the screen working with all these legendary people” (Richard Thomas, Bill Hurt, Swoozie Kurtz, Jeff Daniels, Christopher Reeve, Gig Young, Holly Hunter, Alec Baldwin, Mary Louise Parker, Timothy Hutton, to name a few). Reehling’s first appearance for Judson, however, came straight out of the bullpen. Dawn Wells of Gilligan’s Island fame was cast as Weezer in Steel Magnolias but wound up in the hospital, if just temporarily, instead of on the stage.

“Someone alerted me to Joyce,” says Sills. “She understood the situation. We walked her through it a couple of times and she went on. And she was wonderful.”

Sills thinks the Ephrons’ play is a perfect fit for Reehling. “It’s basically five extraordinary women across the generations, telling the stories, the defining moments, of their lives, via the clothing they had on at the time. So, it’s a piece that shows her tremendous range. Make you laugh; bring a tear to your eye. It’s heartwarming and human and I think it will resonate with everyone. The track of roles Joyce is doing I’ve seen performed by a lot of prodigiously gifted New York actresses, and Joyce is very much in that mold.”

The Reehling/Elms house off Linden Road is filled with art, each piece seemingly with its own secret life. “I love this,” Reehling says, pointing to a painting by James Feehan of figures and poles and shaky equilibrium. “It’s called ‘Tenuous Balance’ and I said, ‘Boy, that feels like my career.’ I wish it had gone on longer. I was never an ingénue, I was always a character girl, and that shortens your life, but women in general have short lives in the theater and film. I can honestly say I can see myself standing in a field near our little red house outside of Baltimore — my father had volunteered us for the job of picking up stones for 25 cents an hour — and I can remember in the back of my head going, ‘How am I going to get from here to where I want to go?’ I didn’t know how I was going to do it, but I did it, one foot in front of the other.” One secret life at a time. PS